North Country Girl: Chapter 35 — The High Cost of College

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

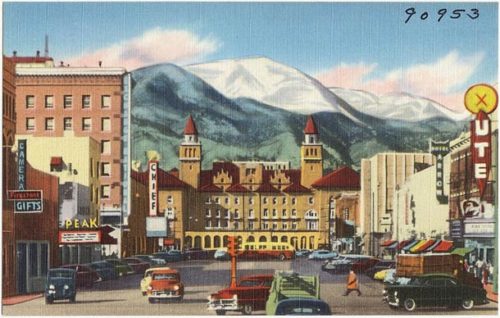

My romance with our dorm’s drug dealer was torrid, tempestuous, and exhausting. It was almost a relief when school ended in June and Steve went off to Outward Bound, to be molested or not, and I went to spend my first summer in Colorado Springs, where my mother had moved in pursuit of her second husband (third if you count her teenage elopement with Bill Bailey, a traveling salesman). My mom, my two sisters, both of them unhappy with the move and miserable in their new schools, and most of our French Provincial furniture from our six-bedroom house back in Duluth were shoehorned into a two-bedroom apartment that had all the character and quality of a roadside motel. Skyway Village Apartments did have a pool, where during the day I sunned and read and tried to ignore our across-the-hall neighbor who kept plopping down next to me to ask why I didn’t own any bras. A few blocks away from Skyway Village Apartments was a restaurant called Mr. Steak, which hired me on the spot before I realized what a complete shithole it was.

Mr. Steak was a grubby, sad place targeted toward unsuspecting tourists on a budget, tourists on their way back from ruining their cars’ transmissions and brakes making the crazy drive 13,000 feet up the top of Pike’s Peak and back down again. The steaks at Mr. Steak looked exactly like rubber dog toys, the baked potatoes were hard as a rock, and most of the lettuce in the skimpy salad was brown. No wonder I so often went home empty-handed. It was amazing that people actually paid to eat that crap, and I should have been grateful that they didn’t slug the waitress who brought it.

I went back to Minneapolis my sophomore year with even less pocket money than the previous fall. I was not returning to the dorm, but to the thrill of a completely unsupervised off-campus apartment. After much cajoling of all parents, my pals Nancy, Liz, and Sarah and I were allowed to leave the protection of the college dorm and move into that rarest of all things, a four-bedroom apartment. My father only agreed because the rent split four ways was less than half of what the dorm cost; I could forage for my own food, or have Steve kill me a squirrel.

Despite the money he saved, my dad was suspicious of the whole set-up and took to making unannounced pop-in visits every time he was in Minneapolis. Early one Sunday morning his pounding on our door woke everyone up and forced us to herd a quartet of half-naked, hungover boyfriends into the farthest back bedroom before putting on robes and nighties and coming out to say hello to Dr. and the second Mrs. Haubner.

We eventually acquired a fifth roommate, my friend from high school, Gretchen. Gretchen was a long-haired hippie chick, with a big heart, a dry wit, and a hooting laugh. Gretchen was also going through a bad time, which we should have suspected when she showed up at our Halloween party wearing only a grass skirt, her breasts painted (with house paint) as twin red, white, and blue targets. Her bad time erupted into kleptomania: Gretchen was a preternaturally talented shoplifter. She was never caught, although after I watched her pull t-bone steaks out of her pants I never again risked going to the supermarket with her. Gretchen slept on the living room couch on top of and under dozens of articles of clothing, all with the price tags still attached. The day Gretchen came back to our apartment proudly brandishing two huge silver candlesticks she had boosted from a Catholic church was the day we put her on a bus back to her family in Duluth. Gretchen did recover, and ended up in Yemen working for the Peace Corps.

My meager savings from waitressing at Mr. Steak quickly evaporated. I found a job at Lancers, a ginormous warehouse of a store, with acres of stacks of jeans—Levi’s, Lee’s, Wranglers—plus weird off brands, in hundreds of colors, styles, and sizes, from pants that would fit a smallish dwarf to ones with a 50 inch waist and 38 inch inseam. My job was to follow customers around, not to help them find a needle in this denim haystack, but to pick up every pair of jeans they had touched, shake them out, refold them, and arrange them back in a perfectly aligned stack of pants. The $2.50 hour I was paid was not enough to make up for the intense hatred I had for every person who walked into that store; I knew their sole intention was to mess up my piles of jeans.

After my first week at Lancers, I realized that everyone was stealing clothes from the joint: the manager, the sales clerks, the delivery guys who dropped off another thousand jeans to be folded and stacked somewhere, and probably even the mailman. Every day more jeans were stolen by the staff of Lancers than were sold to customers. While I would have gladly burned Lancers to the ground, I resisted taking anything until the manager told me that everybody thought I had been planted there by Mr. Lancer as a spy. To prove my innocence, I stole a pair of baby pink, brushed denim elephant bells that billowed around my platform shoes; the three-button fly ended palm’s width below my navel. There were adorable and fit me so perfectly I felt not a twinge of guilt.

The tiny paychecks I got from Lancers managed to cover my living expenses, even after Gretchen left and I could no longer save money by dining on stolen groceries. But I was not earning enough to afford a Spring Break trip to Florida, the Shangri-La of every Minnesota college student. For me, Spring Break was the impossible dream, a dream I indulged while trudging through snowbanks to campus and back, or spending untold hours folding jeans.

As a kid, all winter long I bundled up and went out even in near-blizzard conditions to build snowmen and make snow angels and join the neighbor kids for snowball fights, until the indigo four o’clock twilight fell and I couldn’t feel my fingers or toes and required several mugs of hot cocoa to thaw out. As a teenager winter meant high school ski trips, with shared cigarettes on the chair lift, Fitgers beers bought by the kid with the best fake ID, and the erotic possibility of sitting next to a cute boy on the bus ride home. All through my childhood and high school years winter had enough pleasures to totter on the border between bearable and enjoyable.

For students at the University of Minnesota, the only good part of winter was the anticipation of Spring Break, a week away from snowdrifts and wet socks and chapped cheeks and lips. A week dedicated to the best part of college: boys and drinking. As I folded jeans, I imagined myself wearing a cute bikini and holding an umbrella drink, surrounded by handsome college guys. But every time I cashed my paycheck, I was reminded that it was only a dream.

My roommate Liz, however, was determined to enjoy a real Spring Break, and finally convinced me that for our sanity, the two of us needed to get away somewhere it wasn’t 10 below. Liz claimed to also be short of ready cash (I believe she said this in solidarity, as her father was a prominent Mayo Clinic heart specialist).

Liz and I pooled our money and devised a plan for a Bargain Basement Florida Spring Break. We would buy one-way plane tickets to Daytona Beach, stay at the cheapest place possible, get guys to buy us drinks and meals, and then hitchhike back to Minneapolis. Yes, we were that young and stupid.

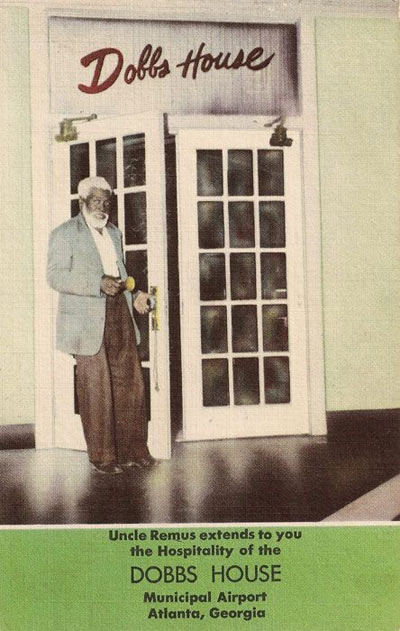

On our flight to Florida, we changed planes in Atlanta with just enough time to have a cup of coffee and split a plate of eggs. A gracious white-bearded black man ushered us into to Dobbs House, the airport cafeteria, where every wall was decorated with murals of Br’er Rabbit and friends in a black-face minstrel style that made Disney’s “Song of the South” look like a contender for an NAACP award. As we sipped our coffee and passed the fork for our scrambled eggs, we were surrounded by the most extreme, pop-eyed, thick-lipped depictions of Uncle Remus, who was himself surrounded by grinning, nappy-headed, raggedy black children. I am sure they had only recently taken down the “No Negros Served” sign: all the customers were white, all the waiters black. Sitting in this homage to racism was shocking; it felt evil, oppressive. (When I was living in Atlanta I could not find a single person who had a memory of these murals, but my pal Liz will attest that they were there.) We choked down our breakfast and ran to catch our plane.

We splurged on a taxi into Daytona Beach and discovered that every motel set their Spring Break prices under the assumption that between eight to ten kids were smashed into a single room. There was nothing Liz and I could afford, as we did not have another six roommates to split the cost of a motel with.

After hours trudging from one place to the next, looking longingly at cute drunk boys and bikinied girls playing chicken in motel pools—just like I had imagined!—we ended up at the Palmetto, an old-fashioned rooming house that had one tiny twin bedded room left. After we had paid our fifteen dollars a night, Liz and I discovered that we were the only people under 80 in the joint, something we should have realized from the pervasive old person smell. The ramshackle house had three bathrooms, one on each floor, which were shared by tenants of both sexes. In a fit of madness on a rainy day, Liz and I locked ourselves in the third floor bathroom, where we dyed my hair blonde while an old man pounded relentlessly on the door, claiming he had to poop.

Worst of all, The Old Folks Arms had a curfew: the front door was locked at midnight. What were those ancient, arthritic codgers getting up to in the middle of the night that they needed a curfew? Liz and I examined the rickety fire escape and decided that we did not want “Spring Break Coed Dies in Fall” to be a headline in the Minneapolis Tribune. We were doomed to be the Cinderellas of Daytona Beach, unable to stay out too late at the ball.

As it turned out, our Spring Break nights ended well before twelve. At nineteen, Liz and I were not old enough to drink legally in Florida. And contrary to what we had assumed, bouncers did not happily allow cute underage girls into their bars.

We spent our days on the famous Daytona Beach, trying not to get run over by the 70,000 cars and trucks zooming across the sands, driven by drunken, cat-calling yahoos. We were determined to go back tan, proof that we had spent Spring Break in an exotic tropical locale. We managed to achieve not too painful sunburns.

We did accomplish our main goal, to meet boys, some of whom actually took us out to nice restaurants, where Liz and I were spared the indignity of being asked for IDs when we ordered our before-dinner White Russians. On our last night we were picked up by two boys from Ole Miss, who had almost impenetrable accents (“Carfish? We’re going to eat carfish?”). We rode in one of their daddy’s Lincoln Continental deep into a pitch dark bayou (“Did he say the restaurant is a fur piece?”). As we bounced around the rutted road, insects smashing by the thousands on the windshield, Liz turned to me and mouthed “Deliverance,” which we had seen the year before. I shot her back a should-we-jump-for-it look just as we pulled up to a shack where I had my first and most delicious catfish and hush puppy dinner and even managed to get tipsy on Dixie beer, as no White Russians or any other cocktails were served.

Liz and I had to cut our Spring Break short, as we estimated it would take us a day and a half to hitch-hike back to Minneapolis in time for our Monday morning classes. After our bayou adventure, we decided we needed to be on guard on our way home.

“One of us should always stay awake in the car.”

“We’re not going to get in if there’s more than one person in the car.”

“No accepting drinks from the driver.”

At seven in the morning Liz and I walked to the curb of the main road heading north, stuck out our thumbs, and immediately got a ride. It was a yellow two-door sedan, dented and rusty, with as expected, a male driver on his own. He leaned over, pushed the front seat down, and opened the passenger door. I clambered in the back so long-legged Liz could have the front. From where I sat, I could see the driver’s pale nape and unfashionably short hair; the rearview mirror reflected a slice of his eyes, shifting back and forth.

“Where you girls headed?”

I had a fleeting fantasy that maybe this guy was somehow a solo Spring Breaker, a fellow Golden Gopher, headed back up north straight to Minnesota. I said “Actually, we’re going all the way to Minneapolis. You wouldn’t—”

Liz jumped in. “No we’re not. We’re getting out here.”

“What Liz, no, we—”

“We’re getting out here!” she yelled while turning around to glare at me, then threw her door open. The car was still moving. The pasty driver hit the breaks, and Liz scrambled out, throwing the seat forward and pulling me out of the car with one motion. She slammed the door, turned and marched back the way we had come.

I caught up with her. “What the hell Liz—”

“He had no pants on.” This fruitcake was driving around Daytona Beach at seven in the morning dressed only in a tee shirt. He must have thought he hit the pervert jackpot when he came upon two blonde nineteen-year-olds looking for a ride.

Liz and I sat on the curb for a minute to pull ourselves together. We had to get home somehow and we had less than $30 between us. Neither of us were about to call our parents; I don’t know how they would have gotten money to us anyway. We waited until we felt sure the pale creep was gone, stood up, and stuck out our thumbs again. The goddesses of youth and hitch hikers smiled upon us: we made it from Daytona Beach to Minneapolis in three rides, all of them with nice guys driving alone, wearing pants. Our third ride was a very concerned dad from Stillwater, Wisconsin, who bought us breakfast and lunch and insisted on driving us all the way to our front door, where he waited until he saw we were safely inside before driving away. God bless you, sir.

In June I shipped my bike out to my mom in Colorado Springs, so I could work somewhere, anywhere other than Mr. Steak. My family’s life at Skyway Village had become even more chaotic. Alimony and child support checks from my dad arrived on a schedule of their own and only after several screaming, threatening phone calls from my mom. A second marriage to the man she had followed out to Colorado did not seem to be happening anytime soon, as my mom’s intended, a former pillar of the Catholic Church and father of six, could not get his wife to divorce him and no fault divorce had not yet been invented. Heidi, my youngest sister, had spent the school year being bullied, beaten up, and having her head shoved in the toilet in the girls’ washroom and probably could have used professional counseling; fourteen-year-old Lani was working illegally at Kentucky Fried Chicken and dating the manager.

I would have been happy to waitress ‘round the clock to get away from that mess, but settled for the eight p.m. to two a.m. shift at Hof´s Hut, a blindingly bright downtown diner a thirty-minute bike ride from Skyway Village Apartments.

During the day, Hof’s Hut was a run-of-the-mill vinyl and stainless diner, breakfast served all day accompanied by bottomless white china mugs of coffee. At night, its neon sign and bluish fluorescent lighting drew an ugly bunch of customers. There were drunken GI’s and even drunker cowboys trying to sober up over hamburgers and chili and cheese omelets before driving back to barracks and bunkhouses. There was always at least one table of heavy-lidded junkies unscrewing the salt shakers to sweeten their coffee. Worst of all were the completely wrecked underage cadets from the Air Force Academy, who even at their most intoxicated believed in their flyboy status. They shoved their hands up my skirt when I refilled their coffee and thought it was hilarious to stagger into me, steadying themselves with a hand grasped firmly on my left tit. They puked in the men’s room, on the front sidewalk, and in the parking lot, and I felt so sorry for the Mexican bus boys and the Sisyphean task they faced every Sunday.

One Saturday night, after six hours of scooping up sticky quarters and grimy dollar bills, wiping down ketchup bottles, and wrestling clammy hands off of my thighs, I wheeled my bike out the back door of Hof’s Hut and headed home, down broad, deserted but very well-lit Colorado Avenue. That half hour of thoughtlessly, rhythmically, pumping my legs, gliding through the warm, quiet night was the one moment of calm in my life. I had just started to relax, loosening up my shoulder muscles when out of the corner of my eye I saw a gleam of white and recognized it as a human being, a man, a man with absolutely no clothes on, who dashed out after me. The adrenaline hit me faster than one of Steve’s Black Beauties and I threw the bike into high gear and Tour de France mode. I cracked my neck back, watched my pursuer dwindle into the dark and wondered: could that somehow be the pantsless guy from Daytona Beach? How had he tracked me here in Colorado Springs?

At least I was making more money than I had at that outpost of hell, Mr. Steak. Drunks tend to overtip cute waitresses. I needed every quarter. I had registered for a grueling schedule of courses for the fall and wanted to save enough money so I could just concentrate on my studies and not have to serve slop to freshmen or fold hundreds and hundreds of Levi’s.

In August Liz called me to report that over the summer our other two roommates decided they had better things to do with their lives than go to college and had dropped out.

“So I drove up to Minneapolis and there were hardly any apartments left, but I found one for us.”

I needed to send her a check to cover my half of the security, first month’s rent, and deposits for telephone and electricity. I scratched down the horrifying large amount and got the OK from my mom to make the dreaded long-distance call. My dad picked up for once; the phone was usually answered by his dumb, heavy-breathing second wife who always lied about him being home. I rushed through the small talk, not caring about what milestones his two toddlers had achieved.

“ I need you to send a check to Dr. Hepper in Rochester, he’s already paid for everything for our new place.”

A few moments of silence passed.

“The divorce agreement says that I have to pay for tuition and dorm. Are you going to live in the dorm again? I’m not paying for you to live in an apartment.” He said the word apartment when he meant whorehouse. My heart sunk. I realized that we had not hidden those boys well enough during my father’s Sunday morning pop-in visits. I hung up, furious.

“Yeah, he’s a jerk,” my mom shrugged. I took a big chunk of my summer savings, bought a money order at the post office, and sent it off to Liz’s dad.

On Labor Day I poured coffee for one last drunk cowboy, cleaned my final ketchup bottles, and turned in my Hof’s Hut uniform. I kissed my mom and sisters goodbye, and my bike and I flew back to Minneapolis.