Gun Cranks and the Spirit of Innovation

Writer Lucian Cary didn’t think he was a “gun crank.” He simply had an enthusiasm for rifle shooting, like other people had for golf, fly fishing, or antique collecting. The difference, Cary assured Post readers in 1935, was that his was “a reasonable enthusiasm. … I do not go in for collecting guns. I never buy a gun unless I really need it. As a matter of fact, I really need a dozen, or say 14, more guns than I have now.”

If he were writing today, Cary might be denying he was a “gun nut”—a term that has gathered some ugly connotations that crank never had. But if you step back from all the political and psychological analyses about gun collectors, you might see there’s little difference between gun nuts and enthusiasts in other fields: all the geeks, devotees, fanciers, wonks, and nerds of our population. There is small difference between the people who fuss over different grades of gunpowder and those who fuss over different database software.

American enthusiasts—whether car restorers, bird watchers, or quilters—are fascinated by details, technique, and different styles. They endlessly tinker with equipment and methods, always trying to make some improvement. They are the tinkerers who gave us radio and TV technology; the inexpensive family sedan and high-performance sports car; the Internet, microbrewed beers, and fantasy baseball.

And, in the 18th century, they were the people who developed the American longrifle, also known as the Kentucky rifle. It was an improvement on the musket and greatly improved the survival odds of the early country and its pioneers.

A traditional rifle of that time required its shooter to literally hammer his bullet into the breech before firing. The Yankee innovation was a greased patch of cloth or buckskin, which was pushed in front of the bullet and into the barrel. In a 1955 article, “All American Weapon,” Ashley Halsey Jr. explained that the greased patch filled the grooves, eased the bullet down, and partly cleaned the barrel when fired out of it.

This innovation made it possible to build rifles with long, slender barrels that didn’t have to endure hammering. “The longer barrel helped the bullet to pick up more speed before leaving the gun. Hence a smaller bullet delivered about the same wallop as the slower, bigger ones then in use. … The smaller bullet required only about a fourth as much lead to make, and half as much powder to shoot, both precious savings in the backwoods,” Halsey wrote.

During the Revolution, General Washington was delighted to find recruits with long rifles who could hit an 8-by-10-inch sheet of paper at 1,300 feet. But they were scarce. Most soldiers of the time used smooth-bore muskets, which were easier to load, though not nearly as accurate. Occasionally a long-barrel marksman might decide a battle by picking off a British general who thought he was safely out of range. The accuracy of the long rifle soon became legendary and proved to have a psychological power as great as its hitting power, as Halsey wrote.

“[A British general was outraged] that certain uncouth American frontiersmen, who wore their shirttails hanging out down to their knees, picked off his sentries and officers at outlandishly long ranges. Forthwith, the general ordered the capture of one specimen, each of the marksmen, and his gun. A raiding party dragged back Cpl. Walter Crouse, of York County, Pennsylvania, with his long rifle. At that point, the British … made a psychological blunder. They shipped their specimen rifleman to London. … Crouse, commanded to demonstrate his remarkable gun in public, daily hit targets at 200 yards—four times the practical range of the smoothbore military flintlock of the day. Enlistments faded away, so the story goes, and King George III hurriedly hired Hessian rifle companies to fight marksmanship with marksmanship.”

In the War of 1812, the Kentucky rifle had a chance to prove what it could do in battle when used in significant numbers. On January 8, 1915, outside New Orleans, Andrew Jackson threw together an army of soldiers, militiamen, pirates, and about 2,000 Kentucky and Tennessee woodsmen to meet men a British force twice its size. When the assault began, the American artillery opened fire but was unable to break the charge. Then, Halsey wrote, “the 2000 Kentuckians and Tennesseans, standing four deep, began taking turns with their long rifles. … At less than 200 yards, the advancing redcoat ranks melted away. … The British lost more than 2,000 killed and wounded; the Americans, eight killed and thirteen wounded. Scarcely ever have battle losses been more lopsided.”

Long after the war, the Kentucky rifle continued to prove its worth. Its incredible accuracy let pioneers and farmers hit predators and game at the very edge of visibility. As Lucian Cary explained, the long rifle meant survival in the wilderness to men like Daniel Boone and the settlers who followed him. “How could Boone have done what he did if he had carried an English Brown Bess, with its smoothbore, its heavy bullets, and its inability to hit what it was aimed at, instead of the instrument of precision he had? He lived by the rifle. He couldn’t have lived by a blunderbuss.”

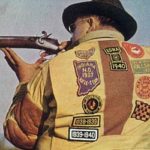

In 1941, Cary’s fascination with rifles brought him to Friendship, Indiana, to the national shooting championship of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association. Here, he was surrounded by gun cranks even more fanatic than himself. And he marveled at the techniques of the champion marksmen.

“Rifle matches are as hotly fought as any other kind of contest. But rifle shooters make every effort to remain calm. They don’t want to talk when they are in a match. They don’t want to laugh or hear anybody else laugh. If they have any walking to do, they walk slowly. They don’t want to raise their heartbeats. They know that one mistake, one bad shot, will make all the difference between a good score and a poor one.

“Their sport requires its own special kind of nerve, the nerve to wait under pressure, to resist the natural human impulse to snatch at the trigger as the sights swing fast across the bull, to hold until the gun steadies, slows down, edges toward the center, and then, promptly but without haste, to put the last necessary quarter-ounce pressure on that trigger.”

Great marksmanship, as Cary described it, sounded like Zen mastery. “When everything is going well, the gun seems to fire itself. But it won’t do that for a man who is excited, or even for one who is trying too hard.”

This week, the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association will again hold its annual championship in Friendship, Indiana, as it has since 1933. Perhaps the event hasn’t changed much in the 71 years since Cary described it “as American as a church sociable, or the Fourth of July, or a horseshoe-pitching contest, and reminded me of all three.” But it will probably still give enthusiasts the opportunity to debate powder, shot, barrel riflings, and shooting technique; in other words, that American mixture of innovation built on tradition.