Mid-Century Bowl-O-Rama

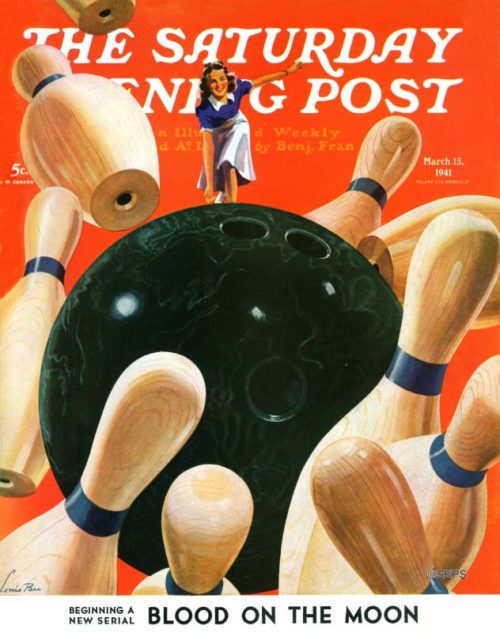

Lonie Bee

March 15, 1941

Bowling was taking over America in 1941. An enjoyable pastime to take one’s mind off of the looming war in Europe, this covers by Lonie Bee showed that it was an activity that could be pursued by women as well as men.

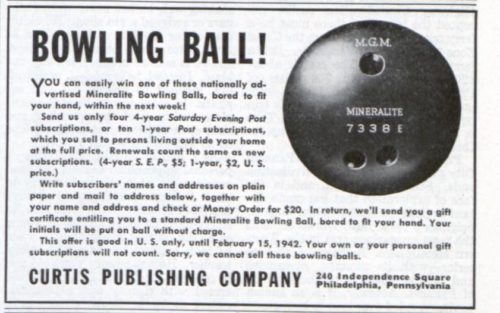

December 27, 1941 (Click to Enlarge)

Bowling was popular enough in the 1940s to serve as an effective enticement for a four-year Post subscription.

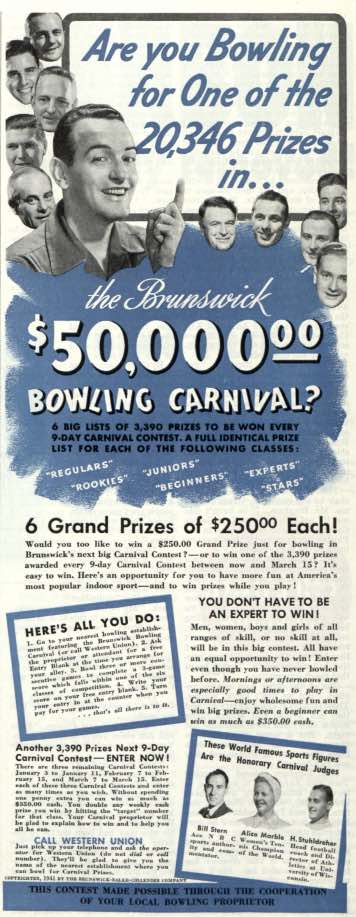

January 3, 1942 (Click to Enlarge)

Who could resist signing up for the Brunswick Bowling Carnival?

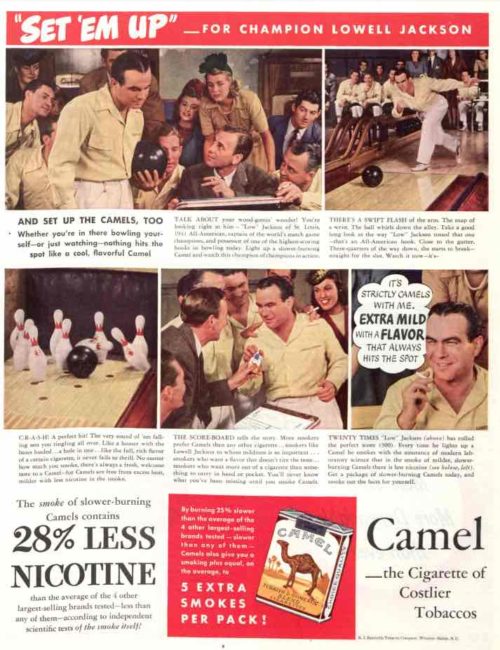

January 31, 1942 (Click to Enlarge)

In 1942, this Camel ad featured bowling champ “Low” Jackson. “Light up a slower-burning Camel and watch this champion of champions in action.”

August 29, 1942 (Click to Enlarge)

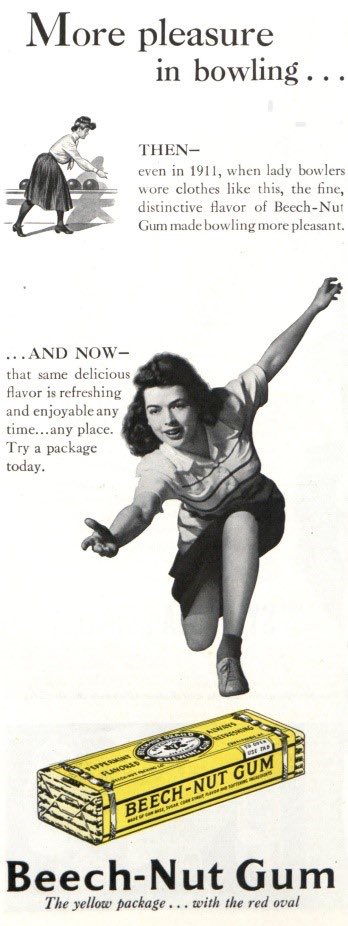

“Even in 1911, when lady bowlers wore clothes like this, the fine, distinctive flavor of Beech-Nut Gum made bowling more pleasant.”

May 1, 1943 (Click to Enlarge)

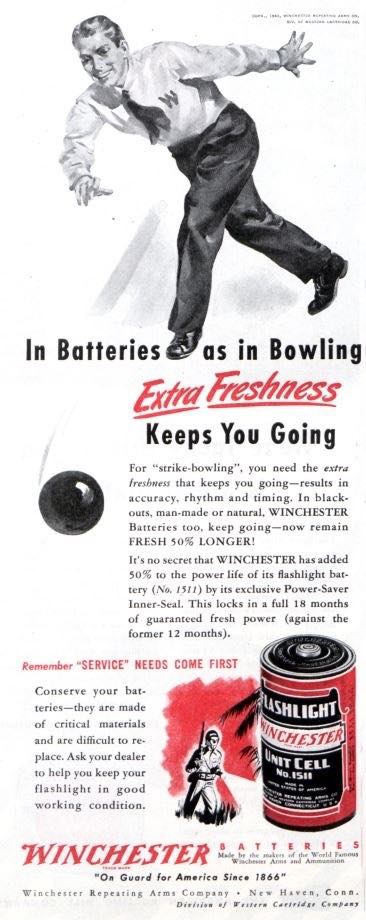

“For ‘strike-bowling’, you need the extra freshness that keeps you going—results in accuracy, rhythm and timing. In blackouts, man-made or natural, WINCHESTER Batteries too, keep going—now remain FRESH 50% LONGER!”

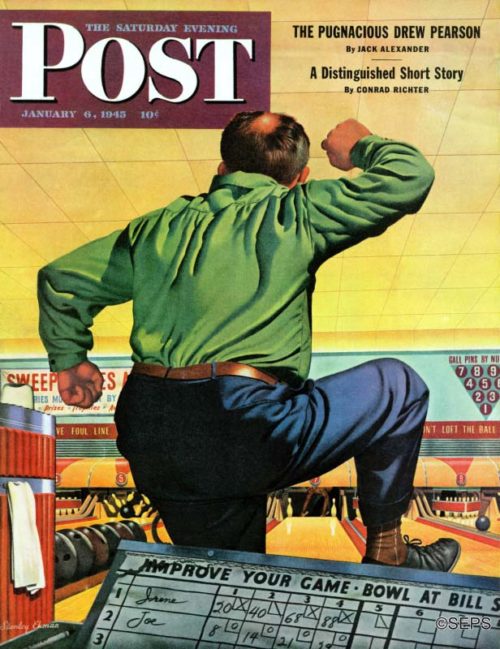

Stan Ekman

January 6, 1945

The idea for this Post cover came to Stanley Ekman when he was having a very tough night on the alleys in his neighborhood Glen Oaks Acres League at Wilmette, Illinois. “To top it all,” Mr. Ekman says, “my wife was trimming me badly.” The interior details of the cover were sketched in the King Pin Alleys in Wilmette and the Arena Alleys, Chicago.

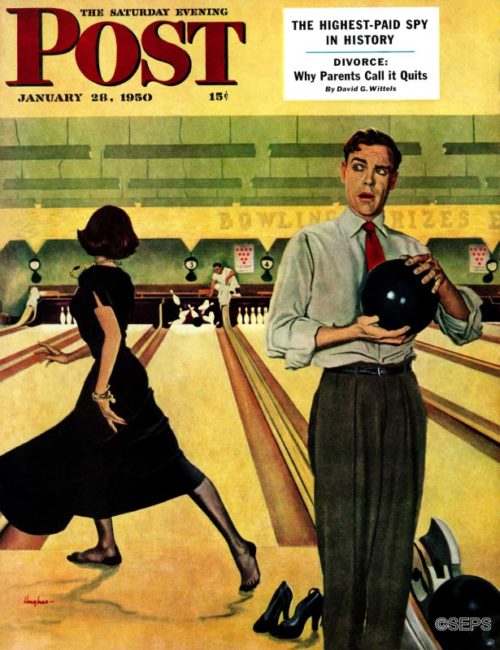

George Hughes

January 28, 1950

What do you do when your date blithely kicks off her heels, grabs a ball, skates forward on her slippery nylons, lets fly, and all ten pins rise into the air and disappear in clattery triumph?

Classic Covers: Gridiron Grit

America is in love with football, and if these Post covers are indication, they always have been. Glimpse into the hilarity and heartbreak of life on (and off) the field.

Alan Foster

November 12, 1927

Not much is known about illustrator Alan Foster, who created more than 30 covers for the Post. His narrative style is reminiscent of Norman Rockwell’s, and his paintings often capture the silly and joyful moments in life.

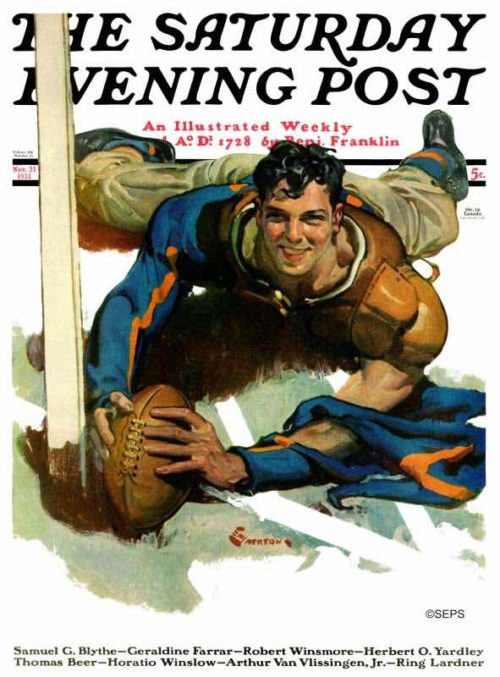

E. M. Jackson

November 21, 1931

An artistic specialty of E.M. Jackson’s was painting women in poses that made them appear seductive and glamorous amidst architecturally authentic backgrounds. Usually, he illustrated for manuscripts involving romance and high society. However, he also illustrated for a wide variety of genres, including murder mystery and (as illustrated in this cover) masculine adventure.

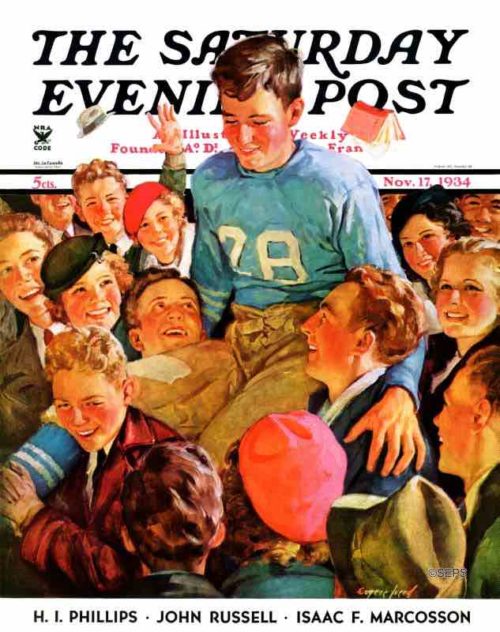

Eugene Iverd

November 17, 1934

Eugene Iverd lived in Erie, Pennsylvania, where he often used children there as his models. Iverd produced 30 covers for The Saturday Evening Post between 1926 and 1936.

Lonie Bee

October 22, 1938

Lonie Bee illustrated 6 covers for the Post, all focused on sports, and most depicting a moment of consternation, whether it was cheerleaders mourning a losing game or a football player trying to sway the ref.

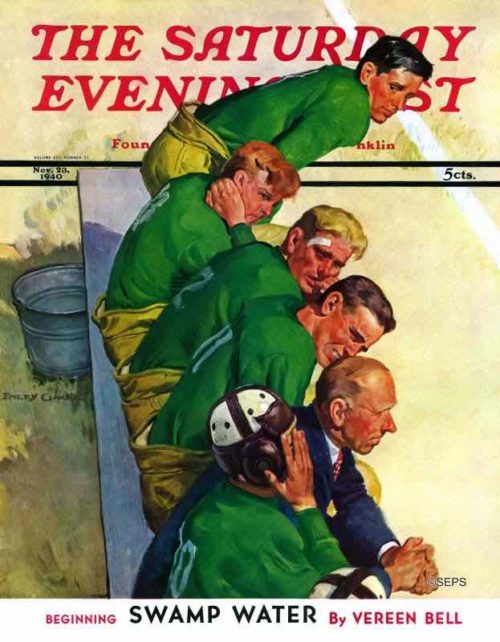

Emery Clarke

November 23, 1940

Emery Clarke was an illustrator of magazine and pulp novel covers, one of the most well-known being the Doc Savage series. He also collaborated with Russell Stamm on the comic strip, The Invisible Scarlet O’Neal.

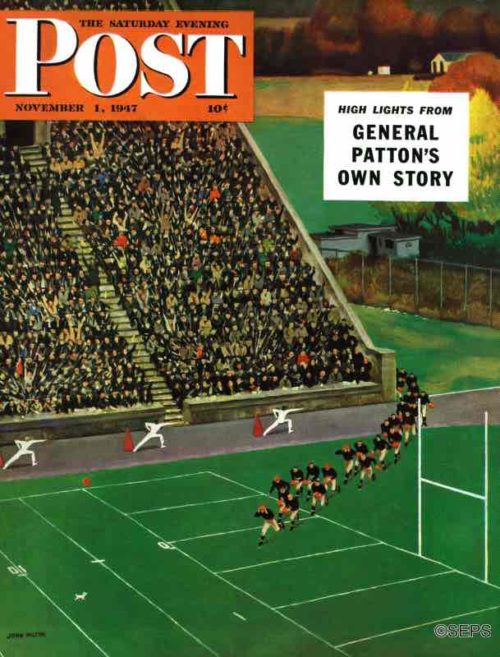

John Falter

November 1, 1947

It seems to John Falter that one of the best moments in football is that curtain-going-up moment when the squads trot out on the field. For one thing, the team in which your hopes are invested always looks pretty good at that stage; even an outfit that is going to take a terrific lacing when the whistle blows can look like champions executing this maneuver. The politic artist said the squad might be that of any school whose colors are orange and black. That takes in a fine range of educational institutions and makes it almost impossible that Falter should have picked a loser. He chose the Princeton stadium for background, and Falter Hypothetical Institute, taking the field, seems to be based on Princeton, without the Tigers’ stripes. (Reprinted from the November 1, 1947 Post)

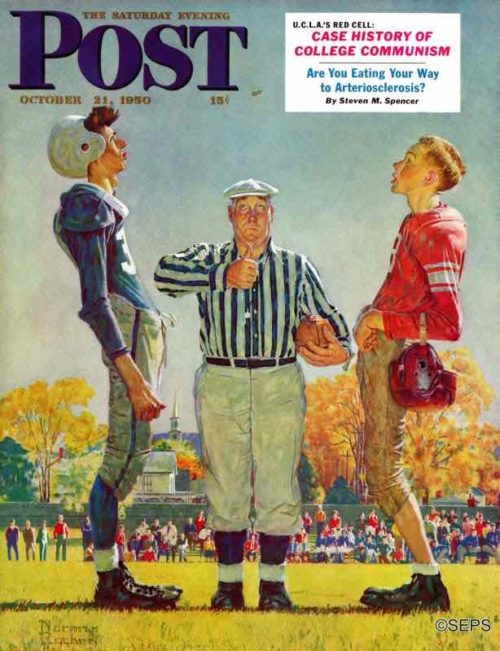

Norman Rockwell

October 21, 1950

With baseball temporarily out of their systems, sport lovers now are concentrating on the gridiron in their constant search for nervous tension. The spotlights of fame play on the collisions of 200-pound colossi in great stadia. But Norman Rockwell reminds us that the super crises are suffered back-country, where Bill Jones, of Mapleville High, strives for the honor of a town where everybody has known him since he was knee-high to a tackling dummy. If Bill wins the game, he’ll not be just a remote newspaper hero, but the idol of the gals in his algebra class and of the mayor he meets walking down the street. If he loses it, the gals will go home teary-eyed, and so may the mayor. “Heads or tails?” grunts Joe Fate, the referee. (Reprinted from the October 21, 1950 Post)

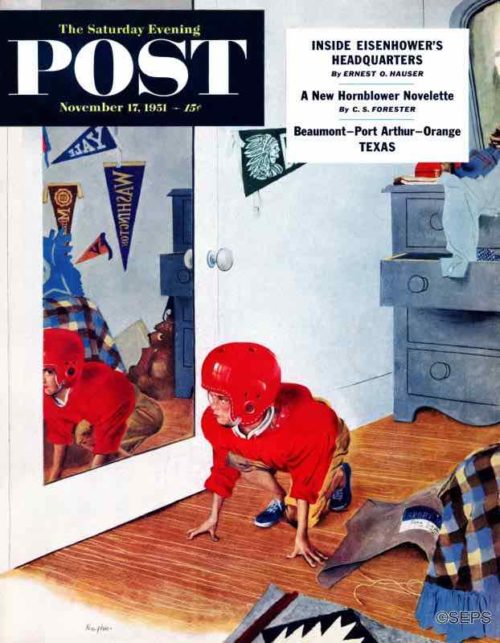

George Hughes

November 17, 1951

This ferocious young grid star, magnified by the terrifying man-from-Mars armor peculiar to football and inflamed by imagination, is about to crunch the enemy’s forward wall, snare a forward pass with his fingertips and weave 70 years down the field for a TD as thousands cheer. Actually, the first play in which he exposes that new uniform to the stark realities of life may see him land on his neck and become a door mat, while some other guy does the crunching. But Artist Hughes says that if this does happen, we can be confident that any lad he would paint will find biting the dust distasteful and will react with such vigor that within a few years he will he offered athletic scholarships to fifteen colleges. (Reprinted from the November 17, 1951 Post)

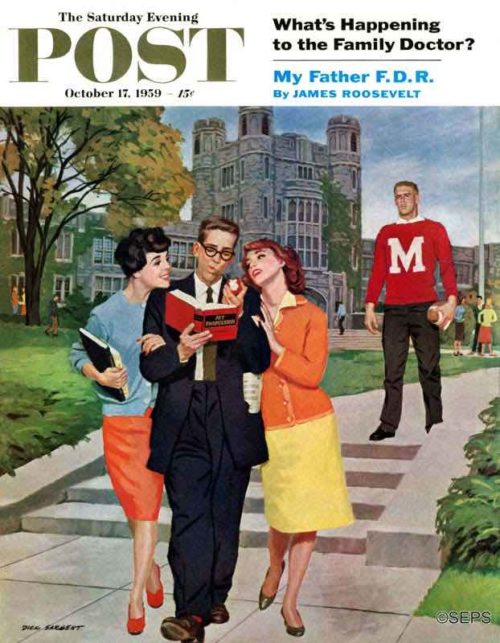

Richard Sargent

October 17, 1959

What strange switch on traditional romance have we here? Those two peaches can’t just be asking for a bite of apple; no, they are applying to a man some seductive apple-polishing with intent to captivate, then capture him. Well, how come that they are chinning themselves on the bony shoulders of H. Arthur Jet and leaving Big M over there looking as if he might break down and cry? Artist Dick Sargent’s theme is that in the fall a young maid’s fancy seriously turns—in these serious days—to thoughts of eventual matrimony, and that H. Arthur is not only a good guy but, being enamored of technology, a potentially good provider. So be it; but let’s not sell Big M short. There is no law against a football star’s becoming another kind of star, too, and lots of them have done so. (Reprinted from the October 17, 1959 Post)

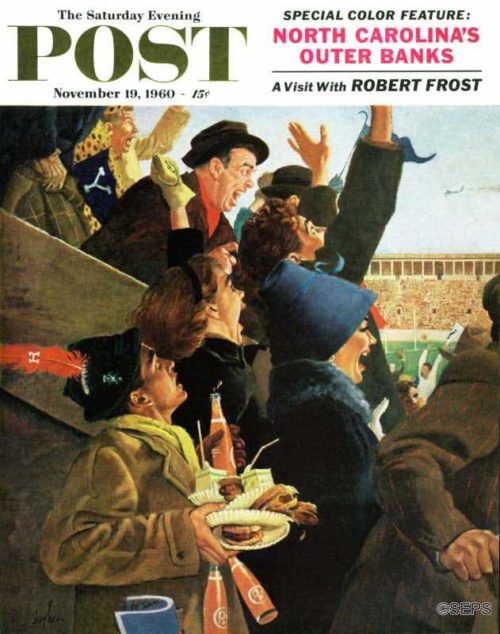

George Hughes

November 19, 1960

The Harvard chap in the foreground is searching for a receiver in the open, but his view is blocked by an exultant pack of Yale Bulldogs. It would seem that while the Crimson was successful at a hot-dog stand, Yale spoiled the attempt at a goalline stand. “Bull-dog! bull-dog! Bow, wow, wow!” shriek the Yale fans, as portrayed by artist George Hughes. (Hughes is neutral. His father-in-law is a Yale graduate, but both his sons-in-law are Harvard.) The Harvard-Yale rivalry commenced in 1875, and Eli Yale has a seventeen-game edge. This week’s combat will be staged at Harvard Stadium — not that the field of battle is likely to affect the outcome. The Bulldogs took a drubbing in 1914, the year the Yale Bowl was dedicated. Yale had the bowl, we read somewhere; Harvard supplied the punch. (Reprinted from the November 19, 1960 Post)