Learning to Grieve

We are left with the impulse. You reach for a glass that isn’t there, and your hand swishes through empty air. You step down and the stair is missing and you stumble into space. Grief is the frozen moment when you pat your pocket for your keys, the pocket where you always put your keys, and your keys aren’t there. The intensely familiar is gone — not just a person, but a habit. Gone. When I do this, that happens. When I say this, you answer. When I reach for you, there you are. And then I am reaching, and nothing, nothing is there. The true has become false.

Grief is disruption. The sound of a footstep on the porch evokes the old world, the other life, and it is only the mail carrier and the new life rushes back. My mother has been gone from my life for more than 30 years, but I hear her voice sometimes when I talk, and I see her in the mirror now and then — sidelong, unexpected glances. There she is. And I think, I should call Mom and tell her about that. Grief recurs and spins, a Möbius strip of memory going on and on in a loop. You aren’t in denial about the death. You just keep remembering that it happened.

You flinch. You know it will hurt and you know it will hurt for a long time. You touch it like an abscessed tooth and skid away. Grief lives in the body. MRI studies show that a grieving brain has a pattern unlike other emotions. Most of the time, an emotion lights up parts of the brain, but grief is distributed everywhere, into areas associated with memory, metabolism, visual imagery, and more. Grief can make you sick; it can be brutal, even deadly. One is coming to grips with what forever means. And we don’t do that all at once and we don’t do it one day at a time but for one minute and then another minute and then another. Don’t ever say: Get over it, move on. She’s in a better place now.

You know it will hurt and you know it will hurt for a long time. You touch it like an abscessed tooth and skid away.

Grief is full of surprises. Anything is possible. You may feel unreal, drugged. Numbness is one of the most common sensations. You may be calm or excited or enraged. You may be so relieved, relieved that it’s over, the illness, the injury, the weeks and months that turned into a waiting room in which no one’s number was ever called. Then you are overwhelmed with guilt for feeling relieved. It’s all very confusing: hard, difficult work. Work! No one tells you that grief is like a long march in bad weather. You’re forgetful and find it hard to make decisions and have no interest in the decisions you are being asked to make. You lose track of time, because time changes, too, shifting and slowing, speeding up, stopping altogether. An hour becomes an elastic, outrageously delicate thing, disappearing or stretching beyond comprehension. One is deranged, in the truest sense of the word: everything arranged has come apart.

In grief, I have baked a cake in the middle of the afternoon and left out the sugar and not been able to figure out why it tasted so bad. I have watched a lot of television and stayed up very late and had many strange dreams that evaporated in the morning light. I have awoken each morning to the shock renewed, to think, He died. She died. Decades of Buddhist practice and many hours at the bedsides of the dying, and all that these have given me in my weeks of acute grief is not acceptance but awareness of not accepting. I can see my disbelief for what it is. I think, He died, and then take a deep breath and reset my compass to this new world. This new world in which a person who had immense influence on my life does not exist. This vacuum. I am dead, too; the me that lived in the other world, the world where she was, died. The me who knew instinctively where he was and suffered a little when he was far away died. Who am I now? All the possibilities of the life of that former me, the me-with-her, are extinguished. Grieving, one is thrust into a new life — an unwelcome life. It takes time for that life to become familiar, to feel like the life you are actually living. You can be happy again, but you can never be happy and the same again.

A friend of mine called the numbness that falls over you immediately after a death “like swimming in thick gelatin mixed with cotton candy and filled with webs and you’re trying to push it aside and you can’t push it aside.” You may not remember much of the days after a death. I remember little about my mother’s funeral, though I did a lot of the organizing. I remember the fight my brother and sister had afterward, the casseroles on the dining table. But I don’t remember how we got the church ready or if there were flowers or what my father did that day or what I wore. I remember sitting in the backyard late that night, drinking bourbon with her friend Hutch, the music teacher who had been my bandleader in middle school. We were drinking and watching the stars, and I was so tired. Nothing will be the same, I thought, leaning back in the chaise longue as though into a pool, sinking into the warm dark night. I remember that.

You have trouble remembering details while the rest of the world forgets the big event. People are almost surprised that you haven’t forgotten, too. What we miss is often the most mundane thing. How she folded a towel. The sound of his foot on the porch. Her handwriting. I keep a recipe card from my mother’s collection on my bulletin board because she had beautiful handwriting and she tried to instill that in me, with little luck. You miss the snore that used to annoy you so. The scent of soap. The pat on the bottom. Small, ordinary things that no one else misses. You can’t say to a grieving person who is suddenly frantic about not being able to do the laundry together that doing the laundry isn’t important. Only the grieving person knows why it is so important, why not being able to do the laundry together is an immeasurable loss. The loss may be accepted in time, but this isn’t the same as “getting over it.” There are so many things not to say now: At least your mother and father are together again. He’s in a better place. You’ll marry again someday.

Crying is neither necessary nor sufficient. The grief-counseling partners John W. James and Russell Friedman write, “During our grief recovery seminars, when someone starts crying, we gently urge them to ‘talk while you cry.’ The emotions are contained in the words the griever speaks, not in the tears that they cry. What is fascinating to observe is that as the thoughts and feelings are spoken, the tears usually disappear, and the depth of feeling communicated seems much more powerful than mere tears. … Tears [can] become a distraction from the real pain.”

Regret is inevitable. Not one of us has lived a life without error. Grief is remorseful. Grief is angry. Angry at the disease, at the terrible choices that had to be made, at the stolen days. Angry at the accident, the mistake, the stupidity of death. Angry at the dead person. How dare you go away? How dare you leave me alone? Angry at everyone involved, everyone who didn’t stop death. We long to blame someone. Why wasn’t she wearing a seat belt? Why didn’t he tell anyone he had chest pain? Why wouldn’t he quit smoking? Anger can be a way for the survivor to deal with the fear of surviving: How do I go on? How do I live now?

Religion doesn’t fix grief. (Don’t say: God always has a plan.) Explanations don’t fix it, advice doesn’t fix it, sharing doesn’t fix it. All these things may help immensely, but grief is not a disease to be cured. Grief is a wound not unlike that from a knife or a bludgeon. The injury will heal in time, leaving a scar, but the tissue is never quite the same. One moves forward, changed.

Grief is the internal experience of loss. Mourning is its outward expression. Together we call this bereavement, a wonderful word. Its root comes from the Old English berafian, which means to rob.

Try not to say: You shouldn’t dwell on the past. Grief is a story that must be told, over and over. Very few people know how to listen to a grieving person without in some way trying to shut down or control the strong emotion. Because it is hard for others to listen, the grieving tell each other the story of their losses, over and over. There are so many things not to say. What are the things to say? I love you. I’m so sorry. And one of the best things to say is Do you want to talk? I would be glad to listen to the story. The story of how you met, of what he was like as a child, of her favorite food, of that trip you took together to Iceland, why he liked that blue plaid shirt so much, what the last moments were like. Whatever story you want to tell.

Sometimes grief isn’t recognized; others don’t understand why you grieve, or grieve with such passion. The loss seems relatively small: a divorced partner, a spouse with end-stage dementia, an early miscarriage. There are no bereavement fares for a best friend or business partner. People may not even realize you are grieving: a secret affair may never be divulged, but the loss is real. This is sometimes called disenfranchised grief. Grief unrecognized or undervalued is real and disabling.

After unexpected or violent deaths, the survivors may feel what is commonly known as complicated grief: pain that remains sharp and unchanging for many months or years. I’m a little wary of this label, because grief has no strict timeline, no prescribed schedule in which one moves forward. But most people do move forward over several months or a few years, even if they think of the dead person every day. A new life without the person in it is slowly created.

The grief counselors James and Friedman developed a program they call Grief Recovery Method, based on James’s experiences after his three-day-old baby died. Their work is based on the idea that unresolved grief happens because “the griever is often left with things they wish had happened differently, better, or more, and with unrealized hopes, dreams, and expectations for the future.” This can be true in healthy relationships as well as dysfunctional ones, anticipated deaths as well as sudden ones. The relationship feels suspended, unfinished, with no way forward. Recovery means, to James and Friedman, letting go of “a different or better yesterday.”

James and Friedman recommend writing a detailed history of the relationship: highs, lows, successes, failures, resentments, joys. Finally, James and Friedman suggest writing the dead person a letter (never to be shown to anyone): a “completion letter rather than a farewell letter.” The relationship as it was is over. Completed. The relationship, however complicated, was whole, had a beginning, middle, and end, had good times and bad.

Very few people know how to listen to a grieving person without in some way trying to shut down or control the strong emotion.

After my mother died, I went through a gradual recovery. All James and Friedman are telling us is to consciously do what people have always done with death. Experience it. I talked to her, I looked at photos, I read letters, I talked to myself, I talked to (and I am sure that I bored) my friends. I told a lot of stories, silently and out loud, about my mother at different times of our life together, her past before I knew her, how she handled her illness, her career as a teacher.

Our relationship improved. We didn’t argue anymore — which is to say, I didn’t argue with her anymore. She listened to me and I told her secrets. As time went on — years, decades — my ideas about her and myself, about mothers and daughters, changed. My memories grew a bit rosy; I had fantasies about what my life would have been like if she’d lived longer. She’d have known her grandchildren, enjoyed her retirement. In my mind she outlives my father and we go to Reno and she gambles all day and we drink martinis by the pool in the summer evening. Happy fantasies. But I know they are fantasies; they are no longer regrets.

Kobayashi Issa was a famous Buddhist haiku poet in Japan’s Edo period. After two of his children died in a short time — two of many losses he would suffer — Issa wrote this poem:

The world of dew is a world of dew, and yet, and yet.

Dew, fleeting and fragile, is the nature of life. While we understand, somehow, that this is precisely what love is — that the china bowl is beautiful precisely because it will break, that we love each other because we do not live forever — we can barely imagine what that means.

A common phrase on 19th-century tombstones went: “It is a fearful thing to love what death can touch.” A part of us holds back from love, always protecting itself, selfish, uncertain. After a death, there is no longer anything to fear. At last. At last, we lose that which we want most to keep. Then there is nothing more to lose. Then the human fears that drive us apart — our concern for the opinion of others, our pride, our shame — are revealed to be so very small. We see what really matters. And when we contemplate the one we have lost, our hearts are free of hesitation, holding nothing back. Grief is the opportunity to cherish another without reservation. Grief is the breath after the last one.

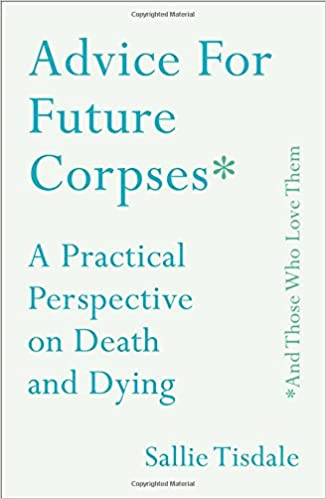

From Advice For Future Corpses (And Those Who Love Them): A Practical Perspective On Death And Dying By Sallie Tisdale. Copyright © 2018 By Sallie Tisdale. Reprinted By Permission Of Touchstone, A Division Of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Sallie Tisdale is also the author of Talk Dirty to Me, Stepping Westward, and Women of the Way. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, The New Yorker, and Antioch Review, among others.

From Advice For Future Corpses (And Those Who Love Them): A Practical Perspective On Death And Dying By Sallie Tisdale. Copyright © 2018 By Sallie Tisdale. Reprinted By Permission Of Touchstone, A Division Of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Sallie Tisdale is also the author of Talk Dirty to Me, Stepping Westward, and Women of the Way. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, The New Yorker, and Antioch Review, among others.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

A Trace of Dampness

I watch them in every season, but they inspire me most in winter. On this steel-cold February morning, they descend on the garbage cans with a madcap shrieking, wing beats snapping time to their plucking and gobbling.

Standing outside McMillan’s Deli, waiting for my bones to chill, I enjoy their fervor. Their table manners are atrocious, but they are survivors. There is beauty in that.

A man steps up beside me.

“I hate seagulls,” he says.

“Herring gulls,” I say.

I recognize him. He is new in town. A retired commodities broker. We used to be a community of plumbers and fishermen. People who worked until they fell over dead. This man is not yet fifty. Brown fur wraps the wrists of his gloves.

He gestures at the shredded donut wraps and greasy paper plates as if commanding them to round themselves up.

“Look at this mess,” he says. “It’s disgusting. Stupid, useless birds. We need to find a way to get rid of them.”

Left alone without a credit card you wouldn’t last two days.

“They’re survivors,” I say.

He turns up the collar of his jacket.

“If that’s what it takes to survive, I’ll pass,” he says.

The birds jostle and peck at each other in the brittle gravel. I wonder if the floor of the Stock Market looks any different.

He takes his leave wordlessly. The door chimes as he steps inside the deli.

My bones are well chilled, but I wait outside just a touch longer. Along the roof line, the rusted rain gutters sag under a five-day garnish of ice. This winter has been unseasonably cold. The ice catches the light of the rising sun and sparkles like tinsel. I take a deep breath of sharp, salt-laden air.

The Caterpillar hats nod as I step through the door. Behind the counter, Jennifer graces me with her prize-winning smile. Lord, a young girl can light up more than a room.

“Top of the morning, Mr. Udall, so nice to see you,” she says, as if she hadn’t seen me yesterday morning and the morning before.

I stand for a moment, enjoying the warmth. It’s why I wait outside. No real pleasure without pain. The heat creeps about me, like a lover’s perfectly planted kisses.

When I step to the display case, Jennifer leans close. She only wears one earring. A tiny silver dreamcatcher. I find this fetching. Piratical. For months now I have been working up the nerve to tell her this. But I worry what she’ll think. What happens to us when we get old? I’ll tell you. We become poster children for hesitation and doubt. You’d think with the end looming, we’d run naked in the street.

Instead I shuffle my feet.

On the other side of the counter, Jennifer leans close. Her eyes flick piratically to her left, where Mr. Scrooge sits alone in a booth.

“My last customer told me you were crazy.” She winks. “I told him we’re all here because we’re not all here.”

No one has winked at me in eight years. Even a wink can fill a heart.

“You are wise beyond your years,” I say.

It will have to do.

“Tell that to my chemistry professor. The usual?”

Jennifer waits a beat, as she always does, as if I might actually order something different.

I think about it. I really do.

Eggs benedict and two mimosas, please. One for me, one for you.

She is already turning. She truly is wise.

“One black coffee and one raspberry donut coming right up,” she says. “And a trash bag for you back in the kitchen.”

“I thank you. My feathered friends thank you.”

“You’re birds of a feather,” Jennifer says.

She stands at the coffee machine, her back to me, but I only half see her.

I think, Are we?

When Marlene was alive we visited an island off the coast of Los Angeles. The island was small, less than one square mile. In those times we walked effortlessly, hiking the island’s perimeter took less than an hour. The island was nothing but beating waves and shrieking sea birds. We went for the birds. Well, I went for the birds. Marlene went for me. She was a slave to all animals, but Marlene’s feelings for sea birds were mixed.

The island was sun-blistered and wind-blasted, and, on the rare occasion when the wind eased, it smelled like a giant guano belch. But as we walked the paths through tawny grasses, my wife smiled and laughed and squeezed my hand. Birds were everywhere. The guide book I carried informed me that the island was home to house finches, horned larks, peregrine falcons, orange-crowned sparrows and even barn owls (“The owls fly silently out from the mainland to dine upon the island’s succulent deer mice,” the author wrote). But all we could see was a vast army of sea birds. Brown pelicans, black oystercatchers, ashy storm petrels and cormorants; in the sun-bleached grass, on the bald escarpments of rock, on the ledges of dark, plunging cliffs, they smothered the island. But mostly there were Hunnish hordes of gulls. Western gulls, to be exact. Many of their nests rested alongside the trails. As we approached, they rose in screaming clouds. Before we got back on the boat, we rinsed our ball caps in the ocean.

On the return boat trip I started a conversation with a ranger. He was heading home after a week-long stint on the island. He was fortyish, and spoke so softly I could barely hear him over the thrum of the engines, but he was kind. He politely answered my questions. When I asked him about the myriad litterings of delicate bones I had seen, assembled in small circles like the aftermath of some horrific Lilliputian battle, he smiled. Chicken bones, he said. Extricating gnawed chicken bits from garbage cans on the mainland, the adult Western gulls gulped them down, flew across the water, and regurgitated them for their young. The gulls also spat up onions, spaghetti, casserole, carrots, chips, dog food and mince. The ranger told me this with an endearing trace of pride. When I said I knew few human beings willing to traverse thirty miles of ocean for a half-eaten chicken wing, he laughed. I told him that, of all the sea birds on the island, the Western gulls were my favorite.

He regarded me through several engine thrums.

“I’m not joking,” I said.

“They’re my favorite, too,” he said.

That night in our Los Angeles hotel room, Marlene stood silent in front of the floor-to-ceiling window. From where I sat on the edge of the bed, I could see her sober reflection in the glass.

The air conditioner purred. In the room above us, a television broadcast the sound of gunshots and screaming. On television, people who are shot have an inordinate amount of time to scream.

Marlene turned to face me. Sequin city lights framed her slender body.

“You don’t know everything,” she said.

“I don’t.”

“I hated every second on that island,” she said.

I almost said, I know.

“All those birds,” she said. “I felt like they could turn on us and there would be nothing we could do.”

She turned back to the window.

“Did you hear it?” she said to the glass.

“Hear what?”

“The sound the gulls made when they first lifted into the air. Right before all the godawful noise.”

“No.”

In the room above us, more people were shot.

“Their wings made the loveliest rustle,” said Marlene. “Like a bag of sand lightly shaken.”

She stood so I could not see her face.

“You can love something, and still be afraid of it,” my wife said. “Sometimes you’re afraid of it because you do love it.”

I understand her fear fully now.

Sometimes late at night in my lonely ranch house on the far edge of Long Island, I see Marlene standing in front of the sliding glass doors to the patio. She is not silhouetted by city lights. The woods behind her are dark. But there is light from somewhere. Possibly, my heart.

“Marlene,” I say softly, “thank you for always holding my hand.”

My wife looks out to the woods.

“That’s what love is,” she says to the glass.

Marlene was ambivalent about birds, but she loved cats with every fiber of her soul. The last of her housecats still resides in our home. Luther is named after Martin Luther King. He is midnight black. Perhaps this is politically incorrect, but it seemed straightforward when Marlene named him.

I have one last cat at home, but I have seven out on the windswept point at the northernmost tip of this island. Marlene and I have cared for a waxing and waning group of feral cats for thirteen years. Well, I have cared for them for thirteen years. Marlene cared for them for eight. It began as a temporary job, filling in for Mrs. Simmons when she went to visit her son in Orlando for Christmas. But people die. So we took up the torch, Marlene and I, caring for the cats dumped in the woods or left behind at summer cottages. On a resort island living is easy for feral cats in summer, with brimming dumpsters and soft-hearted tourists. In February, the tourists are gone and the dumpsters are often frozen shut. The wind howls off the Atlantic like a sodden freight train. The thickest fur isn’t always enough. A frozen cat is the queerest thing. For some reason they are often stretching out at the last. These renders them a little like a boomerang. I confess, I have side-armed a cat or two in the direction of the burlap bag I carry in winter for such exigencies.

The glen where the feral cats live is ten miles from my home. Every afternoon I drive my Ford pickup up the long, empty rises with their vistas of gray, green and blue sea. I look out the windshield, but often I don’t see the road at all.

The glen is pretty and peaceful. After a snowfall, the bare trees preside over the white silence like respectful monks. Sometimes bright sun sparkles the snow, and trilling blue jays hop between the branches. Other days, bruised clouds rule the sky, their shadows passing like dark sleighs over the snow. The cats pad over the ice-crusted snow like furry butterballs. But not always. In my zealousness, I fear I have overfed them. Now and again they plunge through the crust. When this happens there is a wild clawing flurry, and snow flies everywhere. Eventually the cat emerges with a small toupee of snow. I imagine they give me an affronted look. Perhaps they want me to build elevated walkways.

After thirteen years, I still don’t pet the cats. They are wild. They have absolutely no affection for me, though I believe they felt some small affection for Marlene, as almost every living thing did. The cats see me solely as legs ferrying buckets of food. They hear the chunk of the truck door, and they meet me at the opening to the woods. As I carry the two green painters’ buckets, each containing stacked paper plates of dry cat food, the cats follow their wheezing Pied Piper as he makes his way along the narrow path. But when I come to a stop and put the buckets down, behind me the cats ooze away into the woods like the outermost edges of a smoke ring. They don’t trust people. I do not blame them.

Their homes in the glen are simple structures. This is partly because I built them, but mostly because simple is all they require. Plywood roofs rest atop bale walls of hay. The bales, in turn, rest upon a plywood floor. The floors are lined with straw. Straw doesn’t freeze like rug fragments do. More important, straw dries quickly. Cats can stand a lot of cold, but they can’t stand wet and cold. Even on the nicest winter day, a trace of dampness attends the sea. Before Marlene and I learned the difference between straw and rug, we lost several cats. I never tossed one when Marlene was around.

Winter is hard on the birds too. Sometimes a bird will light down on a plate to help itself to dry cat food. Sometimes a cat will take the opportunity to indulge in a two-course meal. It took us only a short time to settle on a solution.

Every day of winter, except for two, I feed the cats the same thing. On Christmas and New Year’s Eve they get chicken liver and hamburger. The extravagance was Marlene’s idea. She also hung tinsel in the trees. One Christmas she decided to put out catnip mice. She stood very still as the cats awkwardly nudged the tiny sacks.

“They don’t know how to play,” she said, and I saw that her eyes were wet.

She kept putting out the catnip mice, along with the tinsel. On Christmas and New Year’s Eve we’d bring hot chocolate and fold out chairs and sit in the glen as evening turned to night, the tinsel catching the moonlight as cat shadows padded about. Women make the world beautiful.

I always feed the birds right after I feed the cats. Keeping them at the truck keeps them off the plates. When Marlene was alive we would make our way briskly back to the empty parking lot. Marlene would get back in the truck. There she’d sit, with the window rolled up, smiling at her husband enveloped in a clamoring cloud of birds. Five years later, I still look over at the truck.

I think about this, and the hundreds of other feckless things that make up a life, as I drive along the empty undulating road to the end of our island. On this afternoon, dark clouds, ragged at the edges, scud across the dishwater sky. At the top of the rises I can see the spread of marsh and the gray Atlantic. From inside the truck I can still smell the sea. I shift in the seat. My back hurts a little. I carry the hefty bag of leftover bagels and bread out the kitchen door and across the parking lot. But always, I must lift the bag into the bed of the pickup. I will accept a sore back over asking Jennifer for help.

At the height of their civilization, Marlene and I cared for nineteen cats. Damp, time, and the occasional road misadventure have seen to the whittling. I do not wish to saddle someone else with the burden. Sometimes I imagine myself peering up into bleak faces from my deathbed. Promise me you’ll feed the cats. But we had no children, and I have no more family. I have no idea who might peer down at me. Perhaps their faces will be bleak only because they fear being asked to care for uncaring cats. But I don’t worry too much about the cats. Like the birds, the cats are tough cusses. The toughest will find ways to survive. I suppose, at any time, I could have just stopped, but I am part of a generation cursed with the inability to quit. And we become creatures of habit. It’s why I brought the hefty bag. I look up into the rearview mirror and smile at my folly.

When I park the truck, I walk around to the back. Leaning over the hatch, I open the bag, carefully rolling back the edges. It is my mimosa.

I do not turn to look back at the truck.

When I reach the glen, I lay the plates out quickly and efficiently. You would expect nothing less from someone who has done this roughly two thousand times.

But this time, when I finish distributing the plates, I don’t leave. I find a spot far enough from the plates, and I sit in the snow. The cats eat warily. Their eyes never leave me.

I look at my watch, as if I have some appointment later this evening. A small part of me wishes I was standing in the parking lot in front of McMillan’s, where, after a time, I might step inside to warmth and the brilliant smile of a young woman who doesn’t really know me, but is kind to me nonetheless. I know this will sting a little, but I also know it will pass. Youth is resilient and has its own concerns. Maybe it won’t pass entirely, but that is okay too. Even on the brightest days, a trace of dampness attends life. But maybe that makes things sweeter. Like stepping into a warm, welcoming deli.

I realize now that, once night falls, a neighbor might notice that none of the lights are on, a small oversight on this preoccupied day. But my dark rancher likely won’t matter. Most of the homes in our neighborhood are no longer ranchers, just as the neighbors are no longer plumbers, fishermen and friends.

It could be a chuckle. It could be my teeth clack slightly.

I lay back in the snow. From this position I cannot see the cats, but I know they watch me as they move among the skeletal trees. They will not come close for a long time. They are survivors.

But sometimes there is no joy in survival.

I don’t have to wait long for my bones to chill.

Featured image: Shutterstock