The Struggles of Judy Garland

Originally published April 2, 1955.

On-screen, she melted the audience’s hearts. But even at the triumphant peak of her career, Judy Garland worried herself sick. The true story of the dazzling, unhappy star.

I dropped in at Warner Bros. studio in Burbank the other day and found the old battleground strangely demure. The absence of Errol Flynn, Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart and Ann Sheridan, who kept things in an interesting uproar a few years ago, was not enough to account for the calm. There was a kind of postoperative shock about it.

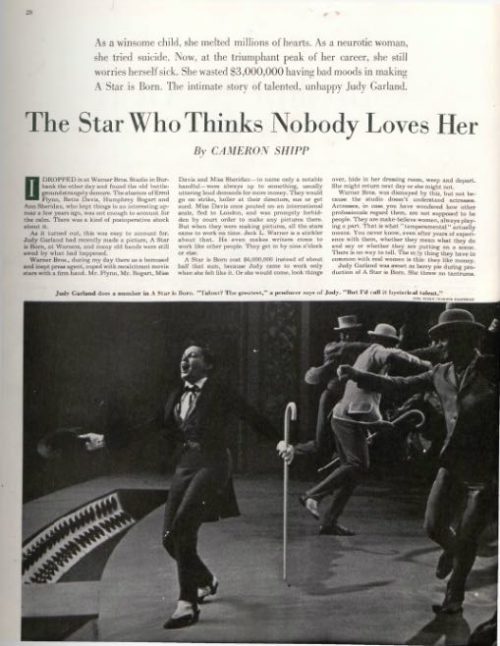

As it turned out, this environmental strangeness was easy to account for. Judy Garland had recently made a picture, A Star is Born, at Warners, and many old hands were still awed by what had happened.

A Star is Born cost $6,000,000 instead of about half that sum, because Judy came to work only when she felt like it. Or she would come, look things over, hide in her dressing room, weep and depart. She might return the next day or she might not.

After finishing this picture, her first in nearly four years, Judy barely had time to sleep late after the premiere before an old and familiar lament echoed through Hollywood. You can hear this bewildering recitative today wherever two or three industry people are gathered together.

It begins invariably with professions of love and esteem. It takes various forms, but the gist is this: “She’s the greatest, that girl. Got the most exciting talent in show business.

Who else can belt over a song like Judy Garland? She’s the greatest, that’s all. I tell you, I love her. I love her, but…”

Judy Garland today is a short, soft-spoken young woman of 32. She has the same naive sort of charm she has exhibited in more than 40 motion pictures. She uses her enormous brown eyes appealingly, like a gracious child. She proves to be an entertaining storyteller and imitator.

On the whole, Judy has made the happiest and most tuneful pictures — but she has been Hollywood’s unhappiest star. Roger Edens, who wrote many of her great song hits, puts it like this: “She ought to enjoy being the enormous international celebrity she is. But she doesn’t enjoy it. She doesn’t know it. She has more talent than anybody who ever came along, but she doesn’t understand that either. Everybody loves Judy, but she thinks nobody loves her.”

When Judy first went to work at M-G-M in 1935, she was 13 years old, thick around the middle and as strong as a pony. She was not especially pretty when Louis B. Mayer and Arthur Freed put her under contract, but she had those swimming dark eyes, a clean fresh kind of charm and the stout torso it takes to sing out a brassy song. She had been singing since she was 3 years old and had been called “little leather lungs.” Years later she said this “leather-lung” title humiliated her — she would rather have been told she was a pretty little girl, or even a nice little girl. Judy liked to sing, everyone at M-G-M recalls, but she hated work and resented authority.

She grew up, literally, before the eyes of millions of spectators.

An Overworked Actress

From the beginning, Judy’s pictures were big, requiring long, wearying rehearsals and recording stints, dancing and acting as well as singing. Judy threw herself into each production as if it were a last-ditch stand. But her closest friends insist that she never wanted to be a movie star at all. She merely wanted to sing and would have preferred to make records for jukeboxes.

She had a tendency toward gaining weight, and M-G-M laid down stern dietary laws to Judy, who responded hysterically: She refused to eat either lunch or dinner and kept up this starvation regime for years. Breakfast and then black coffee and cigarettes for lunch and dinner — four packs a day.

Hedda Hopper tells me she once saw Judy trying to do a dance sequence and almost dropping from exhaustion.

“I’m too hungry,” it’s said she told her director.

“Get on with it and you won’t feel hungry,” the director said.

Long hours of lming and starvation exhausted her, and then insomnia set in. Judy’s solution for that problem: She took pills. The next step was pills to wake her up. She became

a virtual automaton, turned off and on by formulas.

Judy earned $5,000 a week, later $150,000 per picture, and saved not a cent. But where the money went, nobody knows.

Judy ceased to be biddable in 1945. She was world-famous, hungry, sleepy and unhappy. She held up productions, a cardinal sin in Hollywood, wept in her dressing room and cried that no one loved her.

In May 1949, Judy walked out on the studio. It began with her refusal to go on with Annie Get Your Gun, produced by her old friend and admirer Arthur Freed. Judy worked for six weeks, recorded all the songs — now collector’s items — then fled from M-G-M at the lunch hour one day and wailed she could not go on.

She was suspended and taken off salary. She was broke. But it was Louis B. Mayer, head of the studio, who sent her to Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston and paid the bill. Judy stayed there 11 weeks, started to sleep regularly and gained weight.

Then the studio called her back for Summer Stock, produced by Joe Pasternak. “Too fat,” they said again. More hysterics and more delays, but the picture was finally finished. It was not a great picture, but it made Judy’s fans happy.

After this, she went right into Royal Wedding. This one she never finished — again she ran — and Jane Powell was called in to take over. The studio suspended her. The long-term contract was dissolved at Judy’s request. This left her alone, jobless and broke. Her reputation for neurotics, delays and temperament was now so widely known that no producer with a clear head would consider her for a picture.

Road To Redemption

But there was a man named Sid Luft. Mr. Luft, a former test pilot for Douglas Aircraft, once private secretary to Eleanor Powell, the dancer, and by this time an independent promoter, is a handsome and muscular fellow who exudes confidence. Luft had little money and was known only as a clever operator, but he appeared virtually out of nowhere and offered Judy the three things she desperately needed — sympathy, strength and a way to escape from M-G-M. He took it for granted that people mean what they say when they profess to love Judy.

Acting fast on this principle, Luft went to M-G-M and had no trouble at all borrowing Roger Edens, who is under contract there, to write a show. He offered the show to London’s famous Palladium, where only the most reliable stars are considered, and the offer was snapped up. Judy opened there on April 10, 1951, tripped and fell flat on her face before a distinguished opening-night audience.

“Go on, Judy, we love you!” the Londoners screamed to her. She went on in concert pitch and scored a damp-eyed triumph.

Later that year she brought vaudeville back to the great Palace Theater in New York. She was overweight again, but when she sang “Over the Rainbow,” Broadway gave Judy, then 29, the kind of sentimental, sobbing welcome usually reserved for the aged great. There has possibly never been a finer personal triumph on stage. Judy collapsed from overwork after six weeks, but she rested a few days, returned and enjoyed a run of 19 weeks. Night after night, audiences called out the old refrain, “Judy, we love you!”

“That was the real start of the Garland Legend,” Roger Edens says. “She did become legend then, but she doesn’t know it yet.”

Sid and Judy brought the show on to Los Angeles and another tearful, shrilling triumph. In the spring of 1952, after columns of speculation had been printed, they were married near Hollister, California. It looked for sure now as if Judy had lived up to her famed “Over the Rainbow” song and had found, at last, what she could do and how to be happy doing it.

But by the end of the year, Judy faced a traumatic legal battle with her mother, with whom she had been estranged for several years. The unsavory story was rehearsed again in the press, and some who used to say ‘‘I love Judy” decided they were wrong. Judy collapsed and went under the care of a doctor.

When Judy finally emerged, it was to make A Star is Born, at Warner Bros., and, as noted in the beginning, she approached this as fearfully as a child in the dark.

“She was terrified,” Luft said the other day. She hadn’t made a picture in nearly four years. “She thought she was through and washed up all over again. That’s why she made that picture so difficult. But she gave an Academy Award performance, didn’t she?”

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood. This edition can be ordered here.