Civil War Hospital Sketches from Louisa May Alcott

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

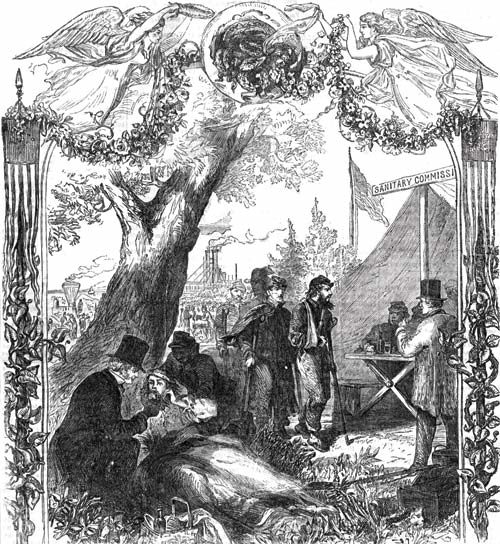

American novelist Louisa May Alcott wrote about her experiences as a Sanitary Commission nurse in a series of letters for the abolitionist Boston Commonwealth. The letters, published as Hosptial Sketches in 1863, earned Alcott her first public attention as an author and praise for her sensitivity and wit.

The Post published excerpts from Hospital Sketches, a few weeks after Gettysburg, when Union hospitals were overflowing with casualties from the battle. On these pages, Alcott describes caring for soldiers from Fredericksburg in December 1862.

* * *

They’ve come! they’ve come! Hurry up, ladies — you’re wanted.”

“Who have come? The Rebels?”

This sudden summons in the gray dawn was some- what startling to a three days’ nurse like myself, and, as the thundering knock came at our door, I sprang up in my bed, prepared “To gird my woman’s form, And on the ramparts die,” if necessary; but my room- mate took it more coolly, and, as she began a rapid toilet, answered my bewildered question, — (“Bless you, no child; it’s the wounded from Fredericksburg; forty ambulances are at the door, and we shall have our hands full in 15 minutes.”)

The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty.

I chanced to light on a withered old Irishman, wounded in the head. He was so overpowered by the honor of having a lady wash him, as he expressed it, that he did nothing but roll up his eyes, and bless me, in an irresistible style which was too much for my sense of the ludicrous; so we laughed together, and when I knelt down to take off his shoes, he wouldn’t hear of my touching “them dirty crayters”.

Some of them took the performance like sleepy children, leaning their tired heads against me as I worked, others looked grimly scandalized, and several of the roughest col- ored like bashful girls. One wore a soiled little bag about his neck, and, as I moved it, to bathe his wounded breast, I said,

“Your talisman didn’t save you, did it?”

“Well, I reckon it did, ma’am, for that shot would a gone a couple a inches deeper but for my old mammy’s camphor bag,” answered the cheerful philosopher.

Another, with a gun-shot wound through the cheek, asked for a looking-glass. When I brought one, regarded his swollen face with a dolorous expression, as he muttered —

“I vow to gosh, that’s too bad! I warn’t a bad looking chap before, and now I’m done for; won’t there be a thunderin’ scar? and what on earth will Josephine Skinner say?”

He looked up at me with his one eye so appealingly, that I assured him that if Josephine was a girl of sense, she would admire the honorable scar.

The next scrubbee was a nice-looking lad, with a a bud- ding trace of gingerbread over the lip, which he called his beard, and defended stoutly, when the barber jocosely sug- gested its immolation. He lay on a bed, with one leg gone, and the right arm so shattered that it must evidently fol- low: yet the little Sergeant was as merry as if his afflictions were not worth lamenting over; and when a drop or two of salt water mingled with my suds at the sight of this strong young body, so marred and maimed, the boy looked up, with a brave smile, though there was a little quiver of the lips, as he said,

“Now don’t you fret yourself about me, miss; I’m first rate here, for it’s nuts to lie still on this bed, after knocking about in those confounded ambulances that shake what there is left of a fellow to jelly. I never was in one of these places before, and think this cleaning up a jolly thing for us, though I’m afraid it isn’t for you ladies.”

“Is this your first battle, Sergeant?”

“No, miss; I’ve been in six scrimmages, and never got a scratch till this last one; but it’s done the business pretty thoroughly for me, I should say. Lord! What a scramble there’ll be for arms and legs, when we old boys come out of our graves, on the Judgment Day: wonder if we shall get our own again? If we do, my leg will have to tramp from Fredericksburg, my arm from here, I suppose, and meet my body, wherever it may be.”

The fancy seemed to tickle him mightily.

Donation notes to Soldiers

Alcott volunteered with the Sanitary Commission, created in 1861 to help organize donations and volunteers. Throughout the war, the Post published Commission news, including the excerpt below.

— Originally published March 26, 1864 —

Some of the marks on the items sent to the sanitary Commission show the thought and feeling at home:

On a homespun blanket, worn, but washed as clean as snow, was pinned a bit of paper which said: “This blanket was carried by Milly Aldrich (who is ninety-three years old) down hill and up hill, one and a half miles, to be given to some soldier.”

On a bed quilt was pinned a card, saying: “My son is in the army. Whoever is made warm by this quilt, which i have worked on for six days and most all of six nights, let him remember his own mother’s love.”

On another blanket was this: “This blanket was used by a soldier in the war of 1812 — may it keep some soldier warm in this war against Traitors.”

On a pillow was written: “This pillow belonged to my little boy, who died resting on it; it is a precious treasure to me, but i give it for the soldiers.”

On a pair of woolen socks was written: “These stockings were knit by a little girl five years old, and she is going to knit some more, for Mother says it will help some poor soldier.”

On a bundle containing bandages was written: “This is a poor gift, but it is all i had: i have given my husband and my boy, and only wish i had more to give, but i haven’t.”

Little Women Among the Casualties

This is the fifth installment of our six-part series on the Civil War, marking the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. To recap: In part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move,” we described how the Post reported the initial news of the invasion. In part two, “Scrambling for Soldiers,” we looked at the renewed attention to the draft. In part three, “Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops,” we covered a special organization of volunteers who helped save thousands of soldiers’ lives. And in part four, “Where the Civil War was Won,” we looked at the Post’s war coverage from the battlefield.

American novelist Louisa May Alcott knew firsthand the terrible price of victory in the Civil War. From 1862 to 1863, she cared for wounded soldiers at a military hospital in Georgetown, D.C.

She wrote about her experiences in a series of letters for the abolitionist paper, Boston Commonwealth. The entire series of letters, published as Hospital Sketches in 1863, earned Alcott her first public attention as an author and praise for her sensitivity and wit.

Five years later, she became one of America’s foremost writers with her classic novel Little Women.

The Post published this excerpt on July 25, 1863, just a few weeks after Gettysburg, when Union hospitals were overflowing with the thousands of casualties from the battle. Here, Alcott describes her first day on duty in December 1862, when the hospital received grievously wounded soldiers from Fredericksburg.

Hospital Sketches by Miss Louisa M. Alcott

“Which naming no names, no offence could be took.”

— Sairy GampThey’ve come! they’ve come! Hurry up, ladies—you’re wanted.”

“Who have come? the rebels?”This sudden summons in the gray dawn was somewhat startling to a three days’ nurse like myself, and, as the thundering knock came at our door, I sprang up in my bed, prepared

“To gird my woman’s form,

And on the ramparts die,”if necessary; but my room-mate took it more coolly, and, as she began a rapid toilet, answered my bewildered question,—(“Bless you, no child; it’s the wounded from Fredericksburg; forty ambulances are at the door, and we shall have our hands full in fifteen minutes.”)

Arrival of the Wounded

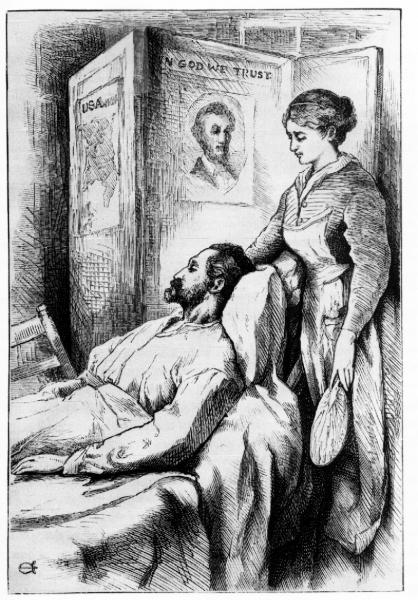

The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty, which was rather “a hard road to travel” just then.The house had been a hotel before hospitals were needed, and many of the doors still bore their old names; some not so inappropriate as might be imagined, for my ward was in truth a ball-room, if gun-shot wounds could christen it.

Forty beds were prepared, many already tenanted by tired men who fell down anywhere, and drowsed till the smell of food roused them. Round the great stove was gathered the dreariest group I ever saw—ragged, gaunt and pale, mud to the knees, with bloody bandages untouched since put on days before; many bundled up in blankets, coats being lost or useless; and all wearing that disheartened look which proclaimed defeat, more plainly than any telegram of the Burnside blunder. I pitied them so much, I dared not speak to them, though, remembering all they had been through since the route at Fredericksburg, I yearned to serve the dreariest of them all. Presently, Miss Blank tore me from my refuge behind piles of one-sleeved shirts, odd socks, bandages and lint; put basin, sponge, towels, and a block of brown soap into my hands, with these appalling directions:

“Come, my dear, begin to wash as fast as you can. Tell them to take off socks, coats and shirts, scrub them well, put on clean shirts, and the attendants will finish them off, and lay them in bed.”

If she had requested me to shave them all, or dance a hornpipe on the stove funnel, I should have been less staggered; but to scrub some dozen lords of creation at a moment’s notice, was really–really–. However, there was no time for nonsense, and, having resolved when I came to do everything I was bid, I drowned my scruples in my wash-bowl, clutched my soap manfully, and, assuming a business-like air, made a dab at the first dirty specimen I saw, bent on performing my task vi et armis (by force of arms) if necessary.

I chanced to light on a withered old Irishman, wounded in the head, which caused that portion of his frame to be tastefully laid out like a garden, the bandages being the walks, his hair the shrubbery. He was so overpowered by the honor of having a lady wash him, as he expressed it, that he did nothing but roll up his eyes, and bless me, in an irresistible style which was too much for my sense of the ludicrous; so we laughed together, and when I knelt down to take off his shoes, he “flopped” also, and wouldn’t hear of my touching “them dirty crayters. May your bed above be aisy darlin’, for the day’s work ye ar doon! —Whoosh! there ye are, and bedad, it’s hard tellin’ which is the dirtiest, the fut or the shoe.” It was; and if he hadn’t been to the fore, I should have gone on pulling, under the impression that the “fut” was a boot, for trousers, socks, shoes and legs were a mass of mud. This comical tableau produced a general grin, at which propitious beginning I took heart and scrubbed away like any tidy parent on a Saturday night.

Some of them took the performance like sleepy children, leaning their tired heads against me as I worked, others looked grimly scandalized, and several of the roughest colored like bashful girls. One wore a soiled little bag about his neck, and, as I moved it, to bathe his wounded breast, I said,

“Your talisman didn’t save you, did it?”“Well, I reckon it did, ma’am, for that shot would a gone a couple a inches deeper but for my old mammy’s camphor bag,” answered the cheerful philosopher.

Another, with a gun-shot wound through the cheek, asked for a looking-glass, and when I brought one, regarded his swollen face with a dolorous expression, as he muttered—

“I vow to gosh, that’s too bad! I warn’t a bad looking chap before, and now I’m done for; won’t there be a thunderin’ scar? and what on earth will Josephine Skinner say?”

He looked up at me with his one eye so appealingly, that I controlled my risibles, and assured him that if Josephine was a girl of sense, she would admire the honorable scar, as a lasting proof that he had faced the enemy, for all women thought a wound the best decoration a brave soldier could wear. I hope Miss Skinner verified the good opinion I so rashly expressed of her, but I shall never know.

The next scrubbee was a nice looking lad, with a curly brown mane, and a budding trace of gingerbread over the lip, which he called his beard, and defended stoutly, when the barber jocosely suggested its immolation. He lay on a bed, with one leg gone, and the right arm so shattered that it must evidently follow: yet the little Sergeant was as merry as if his afflictions were not worth lamenting over; and when a drop or two of salt water mingled with my suds at the sight of this strong young body, so marred and maimed, the boy looked up, with a brave smile, though there was a little quiver of the lips, as he said,

“Now don’t you fret yourself about me, miss; I’m first rate here, for it’s nuts to lie still on this bed, after knocking about in those confounded ambulances that shake what there is left of a fellow to jelly. I never was in one of these places before, and think this cleaning up a jolly thing for us, though I’m afraid it isn’t for you ladies.”

“Is this your first battle, Sergeant?”

“No, miss; I’ve been in six scrimmages, and never got a scratch till this last one; but it’s done the business pretty thoroughly for me, I should say. Lord! what a scramble there’ll be for arms and legs, when we old boys come out of our graves, on the Judgment Day: wonder if we shall get our own again? If we do, my leg will have to tramp from Fredericksburg, my arm from here, I suppose, and meet my body, wherever it may be.”

The fancy seemed to tickle him mightily.

Coming Next: The Work of the Sanitary Commission Inspires Another Convert