Wit’s End: What’s My Love Language? You Don’t Want to Know

Around the holidays, in a year no one could take actual journeys, some of my family members embarked on a journey of self-discovery. One minute they were sitting around the table sharing dumb videos on TikTok; the next minute, they were all experts on their personal “love language.”

They’d stumbled upon an online quiz based on the book The 5 Love Languages. In it, marriage counselor Gary Chapman claims that couples often failed to understand each other’s ways of “expressing and receiving love.” A husband might show his devotion by spending an entire Saturday replacing a broken toilet. The wife might feel hurt that it’s their wedding anniversary and her “surprise gift” is an eyeful of plumber’s butt.

The idea is that, if you know another person’s “love language,” you can tailor your loving behavior so they won’t end up hating you. The online quiz comes in versions for couples, singles, teens, and others.

My husband, 20-something stepdaughter, and preteen daughter took the quiz. After answering a series of questions, they were scored on how much they valued five things: quality time, receiving gifts, physical touch, words of affirmation, and acts of service. The one they valued the most was their “love language.”

Incredibly, after nine months of enforced lockdown, all three of them placed a high value on quality time.

“My main love language is being close to the people I love!” one of them chirped happily across the table.

“Mine too! I feel most loved when my loved one is by my side.”

“My other love language is physical touch. Ideally, I am physically close to the people I love all the time, never more than a room away. I love that!”

As I listened from the kitchen, my blood ran cold. I loved my family, but at this point, togetherness was not at the top of my list. My main love language at the end of 2020 was a solo ticket to Hawaii and $10,000 cash. What I truly desired was a game show jackpot: a fun, life-changing prize for me and me alone!

“Mom! You should take the quiz,” someone called gaily from across the room.

“No. That’s okay. I really have to scrub this tile with a grout brush and . . . can these preserves.”

In truth, I was afraid to take the quiz. The numbers wouldn’t lie; the probing questions would reveal too much. Deep down, my family already suspected I had the “love profile” of a pleasure-seeking misanthrope who wanted to be left alone much of the day. Though I loved being a wife and mom, it could be too much of a good thing, especially now.

Who was going to give me hot stone massages during a shutdown? Who was going to make sure I didn’t grow a thick, dark unibrow like Bert the Muppet? Who was going to utter four of my favorite words — “Pick out a color” — when I needed an hour off to flip through magazines and get my toenails done? Who was going to swing by my Mexican restaurant table and utter six more of my favorite words: “Looks like you need more chips”?

Not these jokers, the ones I lived with. Their love languages included “Mom bringing me a ham sandwich in my room” and “Mom spending an hour every day talking me through Common Core math, a subject she neither likes nor understands.” Every day, I tried to give them the things they loved. No wonder they all gave togetherness high marks!

As for my own preferences, honesty did not seem the best policy. The quiz might dangle things in front of me that I could not pass up, like the ringing silence of profound solitude. What would my family think of that?

I wasn’t about to prove, decisively, that they were all nicer than me.

Eventually, in deep secrecy, I took the quiz. I answered as truthfully as I could, but some of the questions confused me. Many of the choices involved receiving small gifts, or surprise gifts, or thoughtful, just-because gifts. Would I prefer an expensive gift to, say, having someone fold the laundry?

Who the hell would be giving me all these gifts? Trying to imagine this sort of life was a mind-bending exercise. My children were past the age of showering me with drawings, crude pottery, and necklaces made with beads and string. Their gifts to me were now abstract, like “going to church without whining.”

My husband was not a smooth-talking seducer with a diamond in a velvet box in his breast pocket; he was more the toilet-installing type. The task of buying me something seemed to intimidate him a little. I had strong opinions about clothes, jewelry, and pretty much everything else. How could he hope to get it right? Three times a year, he dutifully coughed up a gift, but we were both happier if he did jobs around the house and I shopped for myself.

Because receiving gifts befuddled me, I scored lowest in that love language: a measly 3 percent. My next lowest score, at 17 percent, was quality time. I had a middling interest in physical touch and words of affirmation.

But my highest score by far, at 37 percent, was acts of service. “Absolutely anything you do to ease the burden of responsibilities weighing on an ‘Acts of Service’ person would speak volumes,” the quiz explained. “The words he or she most wants to hear: ‘Let me do that for you.’”

My 12-year-old daughter came upon me pondering these insights. “You finally took the quiz!” she said. “Let me see your results.”

She spent a minute studying my scores with sharp eyes. Then, with a tween’s trademark bluntness, she summed them up: “So, your love language is people being your servant.”

“Don’t tell anyone else about this,” I said.

Then I gave her five dollars to scram.

Featured image: ploy2907; BackWood; Anna Frajtova; Farah Sadikhova; Simakova Mariia / Shutterstock

What Should I Write in My Valentine’s Day Card?

Roses are red, but violets aren’t blue, and if you use this erroneous cliché in a card to your sweetheart they might just dump you.

Is your holiday missive missing something? You needn’t be a brilliant bard to impress your Valentine with some heartfelt verse. Steal it from us instead! Here are some clever and romantic quotations taken straight from obscurity to grace your letter to your beloved.

“Said a Lover” by Katharine Scott (July 12, 1930)

I envy him Love first did give

The idea for the adjective,

Who first did find for passioned state

The barren noun inadequate,

And, leaning to his mistress’ ear,

Made the small words of “sweet” and “dear.”

If I had lived when Love was young,

Before a thousand years of song

Made “lovely” worn and tarnished stand,

And “beautiful” so secondhand;

When “fair” was fresh, and “charming” new,

Perhaps I should have words for you!

From “Song of a Contented Heart” by Dorothy Parker (February 24, 1923)

All sullen blares the wintry blast;

Beneath gray ice the waters sleep.

Thick are the dizzying flakes and fast;

The edged air cuts cruel deep.

The stricken trees gaunt limbs extend

Like whining beggars, shrill with woe;

The cynic heavens do but send,

In bitter answer, darts of snow.

Stark lies the earth, in misery,

Beneath grim winter’s dreaded spell—

But I have you, and you have me,

So what the hell, love, what the hell!

“Any Lover to His Love” by Mary Dixon Thayer (June 13, 1925)

Where you have been the lilies blow

More thickly, and the grass is sweet

Where you have touched it with your feet.

Where you have been, and where you go

The world is fair — so fair!

Your laughter trembles in the air.

Where you have been I wander, and

The lilies and the grass

Utter your beauty as I pass.

Even the blind clouds understand

What loveliness by all is seen

Who walk where you are, or have been.

“Juliet on the Balcony” by Howard Glyndon (January 12, 1878)

O lips that are so lonely

For want of his caress;

O heart that art too faithful

To ever love hint less;

O eyes that find no sweetness

For hunger of his face;

O hands that long to feel him

Always, in every place.

My spirit leans and listens,

But only hears his name,

And thought to thought leaps onward

As flame leaps unto flame;

And all kin to each other

As any brood of flowers,

Or these sweet winds of night, love.

That fan the fainting hours!

My spirit leans and listens,

My heart stands up and cries,

And only one sweet vision

Comes ever to my eyes.

So near and yet so far love,

So dear yet out of reach,

So like some distant star, love,

Unnamed in human speech!

My spirit leans and listens,

My heart goes out to him,

Through all the long night watches,

Until the dawning dim;

My spirit leans and listens,

What if, across the night

His strong heart send a message

To flood me with delight?

“A Question of Terminology” by Robert Zacks (February 16, 1946)

How absurd a heart can be!

When it’s bound, it feels most free.

When it’s free, it wanders round

Seeking, so it can be bound.

All this simply means to me

Words do not say as they sound;

Freedom’s not till love is found.

From “Love Song” by Charles Gavan Duffy (June 21, 1856)

The face of my Love has the changeful light

That gladdens the sparkling sky of spring;

The voice of my Love is a strange delight,

As when birds in the May-time sing.

Oh, hope of my heart! Oh, light of my life!

Oh, come to me, darling, with peace and rest!

Oh, come like the summer my own sweet wife,

To your home in my longing breast!

“The Sum Total” by Patience Eden (November 15, 1930)

In casting up some old accounts

Of psychological amounts,

I find, my dear, you have a way

Of being far more good than gay:

And when I think you’re most alive,

You’re merely bland instead of blithe,

You have a cool and classic mind,

Less brave than bright, more keen than kind;

The values of your character

Merge in a grand, majestic blur

Of awesome traits — and yet, my dear,

It’s what you’re NOT which seems most clear.

“Contentment” by Philip I. Blakesly (March 16, 1940)

When an ocean is least,

Or a world or a star,

Who cares what is most?

When the cup is full,

When the heart overflows,

There is only that —

There can be no more.

And a cup will suffice for a grander measure;

When the mind’s at rest, what more is a treasure?

Love and Haight: The 50th Anniversary of the Summer of Love

How best to sum up an acid-inflected, flower-powered, whirligig of a long-ago summer in San Francisco? How to understand the lasting impact of that summer, which took root in a full-on Age of Aquarius neighborhood and blossomed into a counterculture that splattered across the planet?

Perhaps it’s fitting to begin by describing its final day.

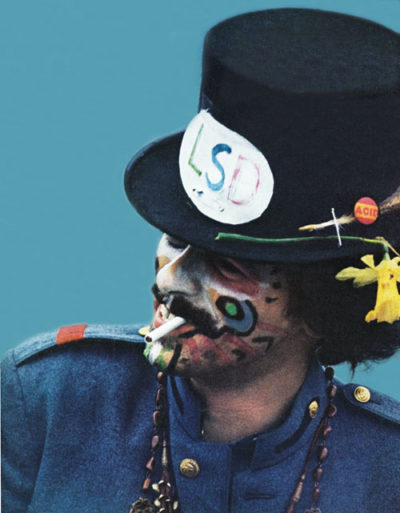

On October 6, 1967 — exactly one year after California lawmakers voted to ban the drug LSD — several hundred young bohemians gathered in the City by the Bay for what had been advertised as “The Death of the Hippie” funeral. Surviving film footage depicts a surprisingly carnival-like atmosphere. There was dancing in the streets. Someone played “Taps.” Sullen pallbearers carried aloft a large coffin that bore a single inscription: “Hippie, Son of Media.”

And that, ladies and gents, is how — officially and weirdly — the so-called Summer of Love concluded. Groovy.

The woman who organized the mock funeral, Mary Kasper, explained that following a season of merriment, music, confusion, and ultimately chaos in the streets of her city’s Haight-Ashbury district, “we wanted to signal that this was the end of it … don’t come here because it’s over and done with.”

Where once The Haight was iridescent with tie-dyed fabrics, colorful blooms, psychedelic storefronts, and a heady pharmaceutical culture, it had become, by October of ’67, a gritty tourist attraction. Worse, it had devolved into a magnet for thieves who’d descended from all around to prey on the vulnerable longhairs who had overstayed their welcome.

The Summer of Love, as initially conceived, was a brilliant marketing scheme. It was intended from the outset to be a convulsion of music, sex, and radical nonconformism. Come to The Haight to “turn on, tune in, drop out,” as Timothy Leary, the high priest of West Coast psychedelia, often exhorted his acolytes.

So, you might fairly ask, was the allure for young Californians the easy access to mind-altering drugs and sex?

Or the throbbing psychedelic music?

Or was it the gathering of the district’s anti-Vietnam War activists?

Yes.

Against the backdrop of a country in turmoil, here would be an aphrodisiacal admixture that some 100,000 people would find too tempting to pass up.

The whole thing sprang to life easily enough in the vibrant tapestry of The Haight, but by the time of the symbolic Hippie Funeral, the Summer’s mixed-up, mixed-media message had wafted across America and far beyond. The hippieverse had metastasized into a veritable, if not universally embraced, worldwide phenomenon.

From New York to London to parts of Asia, the hippie lifestyle was observed by onlookers with a combination of amusement and condemnation. It was a thing of kaleidoscopic beauty, to be sure, but some also thought it was a thing reeking of despair.

Ted Streshinsky, © SEPS

Today, 50 summers on, the questions remain: “What the hell was that all about? Was it, like, too far-out, bro?”

Those were the first questions I put to Dan Lewis, a Northwestern University social-policy professor and proud former hippie. Lewis will oversee the school’s Summer of Love Conference, taking place this July in San Francisco. “Over the years, I’ve been trying to make sense of that period,” Lewis told me when we talked. “There have been all these snarky, nasty, make-fun-of-kids-who-were-stoned people,” he said with an undisguised tone of contempt.

No matter what you may think of the Summer of Love, said Lewis, who runs Northwestern’s Center for Civic Engagement, what happened during that brief season has had a lingering influence on our way of life. For example, it led to the development of Silicon Valley.

Excuse me? You heard that right. According to Professor Lewis, some of the research (not his) that will be presented at the conference will trace “a lot of early thinking about information and communal groups and how that evolved into the Whole Earth Catalog, and then the internet, and then into cyberculture and eventually Silicon Valley.” The hippies are to blame for our smartphones! Well, sort of. And for the record, Lewis swears he no longer drops acid.

Actually, without too much of a stretch, you can make a pretty credible case for the argument: The deployment of social media on a global scale, pioneered by Facebook, was foreshadowed by what happened in 1967 at the intersection of Haight and Ashbury streets, where once stood the funky Unique Men’s Shop.

When I asked around among people who were there at the time — all of whom boasted that they still retain their hippie ideals, if not the iconic wardrobes — the underlying theme of that summer was not free love or LSD or rebellion against the distant war as expressed in the music. It was, fundamentally, a simple, sweet sense of community.

Ted Streshinsky, © SEPS

Among the astonishing catalogue of memorable songs that marked the summer of ’67 (“Good Vibrations,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “White Rabbit,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Light My Fire,” and “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” are but a sample), I was told over and over again that it was the Youngbloods’ “Get Together” that most perfectly captured the spirit of The Haight:

Come on people now,

Smile on your brother,

Everybody get together,

Try to love one another right now

Consider: It may have taken a while, but it was left to Mark Zuckerberg — not yet born in ’67 — to figure out how to connect latter-day hippies — and practically all other living persons — into a true worldwide community where everyone could in fact “get together.” Facebook, one might contend, is the natural evolutionary product of what the Youngbloods and their fans started.

In part because the hallucinogens raised consciousness (though not always mental acuity), hippies left us other gifts besides their remarkable music. The notion of recycling, for example. Scott Guberman, who plays in a Bay Area band with Phil Lesh of The Grateful Dead, told me that “the idea of recycling garbage came from the Summer of Love. The hippies were always concerned about sustainable living.” The whole organic movement, too, according to Guberman. But wait, there’s more. Credit the hippies for yogurt’s success in America because, Guberman told me, they “popularized” the treat.

It’s somewhat easier to link the lifestyle of the hippies to medical research now under way to use hallucinogens to help people quit smoking, break free of addictions, overcome depression, and more. For a long time, as a backlash to the recreational uses of these drugs, it was very difficult to get access to them for such research, but in recent years, that’s been changing. According to The New York Times, for example, such reputable institutions as New York University and Johns Hopkins University are studying the potential of psilocybin, the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms, to help terminal cancer patients face up to and accept their mortality.

If, in 1967, hippies “perceived these illegal drugs as a sacrament which was taken to achieve spiritual enlightenment,” as William Schnabel wrote in his book Summer of Love and Haight, they could never have imagined how legalized forms of these same substances would one day be sought by thousands of ailing patients. The apothecary that was The Haight helped give birth to these important scientific breakthroughs.

It also, unfortunately, led to serious issues with abuse of opioids. Sheila Weller, who has written extensively about the Summer of Love in Vanity Fair, said to me in a text message that “the mindset has endured a lot. … Taking drugs became hip, and the kids who could rebound and go back to their lives and their educations were the middle- and upper-class kids. The lower-class kids have spawned a second or third generation of opioid addicts.”

Lost in all of this is a small but telling irony. A free clinic that opened in The Haight in 1967 — it was designed to help heroin addicts — has recently been absorbed into a multimillion-dollar medical conglomerate named (wait for it) HealthRIGHT 360. Very corporate.

Jim Marshall Photography LLC

In many ways, the ’60s was a pivotal decade in American history — let’s just stipulate to that point and move on — but 1967 was the year of ultimate highs (pun intended). The celebrating and the innovating were likely connected, less by networking than by LSD and the Panama Gold grass, which could be easily had at the “happenings” and “Be-ins” in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge.

“All the creativity, the experimentation, the music — hell, ’67 was when we saw the rise of FM free-form radio and its influence,” Neal Mirsky, a longtime rock-radio program director, told me when we sat down to discuss the era. “It’s the first time we even looked at popular music as art. It was just such a transformational time in a lot of ways.”

The Haight, not surprisingly, was a sort of ground zero for all that. Writing not long ago about a concert that occurred one night in the neighborhood’s famed Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco Chronicle critic Joel Selvin observed, “Everybody who found their way there knew how wonderful the whole thing was and immediately embraced everybody else as fellow members of a special secret society.”

Vivian Murray, who was a high school kid hanging in The Haight during the summer of ’67, remembers that, for her crowd (and presumably Janis Joplin, who briefly lived in the same apartment building), the Summer of Love was driven not so much by utopian ideals but rather by an inchoate urgency to break away from The Man. In essence, to join that special secret society. “It was just our way of gaining freedom. The music scene had a huge effect. We’d escape into that.”

Alas, Murray, who went on to work a series of jobs, including in property management, doesn’t think the spirit of that summer will ever be resurrected. “We were into peace and love. Today’s kids are into video games: action, violence!”

In an effort to hold on to those memories, Murray maintains a Summer of Love shrine in her Washington State home — a room decorated with period furnishings and art. “And I still have my hippie beads,” she told me proudly. Old hippies die hard.

Ted Streshinsky, © SEPS

Witness Joe Tate, who was lead guitarist in Salvation, a psychedelic rock band that performed around San Francisco in the ’60s. Tate, who today continues to dress “like an unkempt hippie,” currently lives north of the city, in Sausalito. He boasted, “I still feel the same way about everything. I didn’t turn into a conservative. I see injustices every day.”

“Any chance of a hippie resurgence someday?” I asked. Unlike Vivian Murray, Tate is decidedly optimistic. “It could happen,” he said. Turns out he’s one among probably many thousands who’d welcome a hippie redux. When a British-based group organized for the purpose of celebrating the Summer of Love’s 50th anniversary — there are scores of such groups, thanks to the internet — it posted all its plans. On Facebook, of course. The final agenda item was an immodest throwback to 1967: “Save the world.”

Neato.

Cable Neuhaus writes about popular culture for the Post and other publications.

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Love and Democracy: A Troubled Romance

The wildest idea of the 18th century was that humans could form their own government and rule as equals.

The craziest idea of the 19th century was that romantic love was more important than social responsibility.

In the 20th Century, the two ideas collided.

Both ideas assumed there was virtue in self interest. The American Revolution was based on a belief that citizens could shape their personal destiny, and form a society where they could all pursue the happiness of their choice. The Romantic Revolution sprang from the assumption that the human spirit could only be fulfilled by allowing people to live true to their passions.

For most of our history, Americans adopted only part of the Romantic manifesto, ignoring its more self-centered aspects. Love led to marriage, which was a lifelong commitment. (American society disapproved strongly of divorced adults and single parents, and was not to supportive of single adults, either.) The stability of marriage, and the lack of romantic experimentation, produced a strong, if not contented, society centered on family life.

A common code of morality — which was often promoted more than it was practiced — helped give the young, disjointed nation a sense of unity. But ultimately, Americans wanted the right to define morals for themselves and their families. Their desire for romantic fulfillment eventually parted with the need to contribute to the common good.

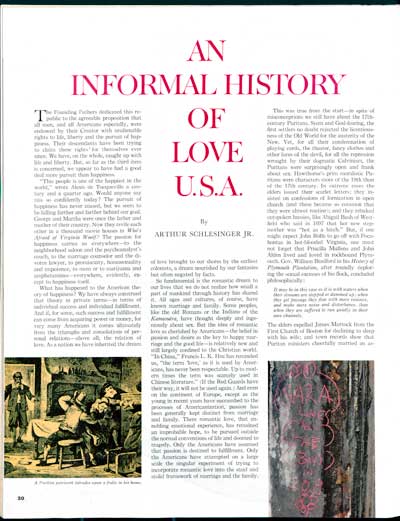

According to Arthur Schlesinger, America’s moral code collided with personal ideas of romance and fulfillment in the early 20th century. In his “Informal History of Love U.S.A.” he observes,

“How shocking at the time were the first intimations of sexual liberation just before the First World War; how innocent they seem in retrospect! War itself hastened the disappearance of the old inhibitions, bringing back from France a new generation determined to live life to the full. The success of the feminist movement increased the pressure against the double standard. The psychology Sigmund Freud gave the role of sex in life a fresh legitimacy.… And, as the new psychology and the new leisure encouraged romantic love, so the new technology simplified life for romantic lovers. The automobile offered lovers mobility and privacy at just the time that contraceptives, now cheap and available, offered them security. Advertising and popular songs incessantly celebrated the cult of sex. Above all, the invention of the movies gave romantic love its troubadours and its temples of worship.”

It was inevitable that American society would redefine its morals. The old Victorian model was invasive, unproductive, and — in time — hypocritical.

However, the redefining moral seemed to go on continually. America couldn’t seem to settle on a new code for romantic and sexual norms. By 1966, when Schlesinger was writing this Post article, lasting love, and marriage was definitely in trouble.

“…the Age of Love has hardly turned out to be an age of fulfillment. If sexual repression failed to produce happiness in the 19th century, sexual liberation appears to have done little better in the 20th. More than that, while repression at least preserved the family, if at times by main force, the pursuit of happiness through love is now evidently weakening the family structure itself. Divorce, of course, is an expression of the determination to make romance legal at any cost: so, if one marriage fails, another must be promptly started; and the steady increase in divorce in these years — the rate trebled from 1900 to 1960 — suggest how the pursuit of love is paradoxically leading to the breakdown of marriage. Freedom, instead of resolving the dilemmas of love, is only heightening anxiety.”

Mr. Schlesinger might have thought divorce a license for continual romance in 1966. It would be interesting to know what he thought four years later when he divorced his wife of 30 years.

According to Elizabeth Gilbert, an enlightened society that allows people to choose their own partner will eventually have to give them the right to separate from that partner. In her recent book Committed: A Skeptic Makes Peace With Marriage, she shares “the single most interesting fact I’ve learned about the entire history of marriage: Everywhere, in every single society, all across the world, all across time, whenever a conservative culture of arranged marriage is replaced by an expressive culture of people choosing their own partners based on love, divorce rates will immediately skyrocket. You can set your clock to it.”

In the same 1966 issue in which Schlesinger’s article appeared, the Post published results of a Roper survey about marriage. It begins with the now-familiar lament about America’s vanishing morals.

“There is a widely held conviction, almost an unquestioning assumption, that the moral quality of life in this country is changing for the worse. Fully half of us believe that the amount of closeness and love in the average American family has declined since we were children, and very few think that it has improved. Even young men and women just arrived at adulthood sense a loss of grace in family life in the few years since they were children. And more than two thirds of us, young and old, are convinced that sexual moral standards in America are worse than they were a generation ago—part of the same pervasive impression of old and good values fading away.”

And yet, “when Americans are asked to answer questions about their own conduct and views, and those of the people they know best, a quite different picture emerges of the state of love, marriage and morality in the United States.” According to one statistic, “Today’s Americans generally feel that they are more happily married than their parents were.”

Since 1966, the divorce rate has continued to climb. Marriage is declining, partly because couples are deliberating more before committing (43 percent of American adults now define themselves as ‘single’), and are marrying later. They are also postponing marriages until the economy improves, just as couples did in the 1930s.

The odds against lifelong love and marriage are high, but a majority of couples think they are doing better than the previous generation. A CBS News Poll from last month reported that 55 percent of the Americans they surveyed thought their marriages were better than their parents.