The Rise of the Black Activists

This is the fifth installment in our six-part series, “The Long March on Washington.” In part one, “It’s Our Country, Too,” we looked at the limited wartime opportunities for black Americans in the 1940s. In part two, “Black Neighbors, White Neighborhoods,” we covered integration in neighborhoods throughout the 1950s. In part three, “Black Students, White Schools,” we reported on integration in the classroom. And in part four, “The Deep South Says ‘Never,’” we covered the White Citizens’ Councils campaign to shut down the movement toward integration.

By 1963, the Post was calling it a “revolution.”

In a July 13, 1963, editorial, the authors conceded it was a harsh word. “But there is no denying black forces are drawn up in a battle line that confronts the white man wherever he stands on the principles and practices of segregation.”

Black Americans’ struggle for civil rights had become a revolution, they said, “because the rule of law has failed … the voices of reason have not been heard.” Consequently, the nation had a duty to “accommodate the legitimate aims of this Negro revolution with as little violence and damage to our society as possible.”

Only a few years earlier, the Post’s reporting on civil rights had presented black Americans as generally background players—passive figures quietly enduring centuries of prejudice. All the initiatives seemed to be taken by white politicians or segregation groups like the Klan or White Citizens’ Councils.

But that changed in 1960, as black activists became the protagonists in their own history. As Ben Bagdikian wrote in his 1962 Post article, “Negro Youth’s New March on Dixie,” the country was seeing “the first generation of American Negroes to grow up with the assumption, ‘Segregation is dead.’” And now this new generation had launched a broad offensive in the fight for civil rights.

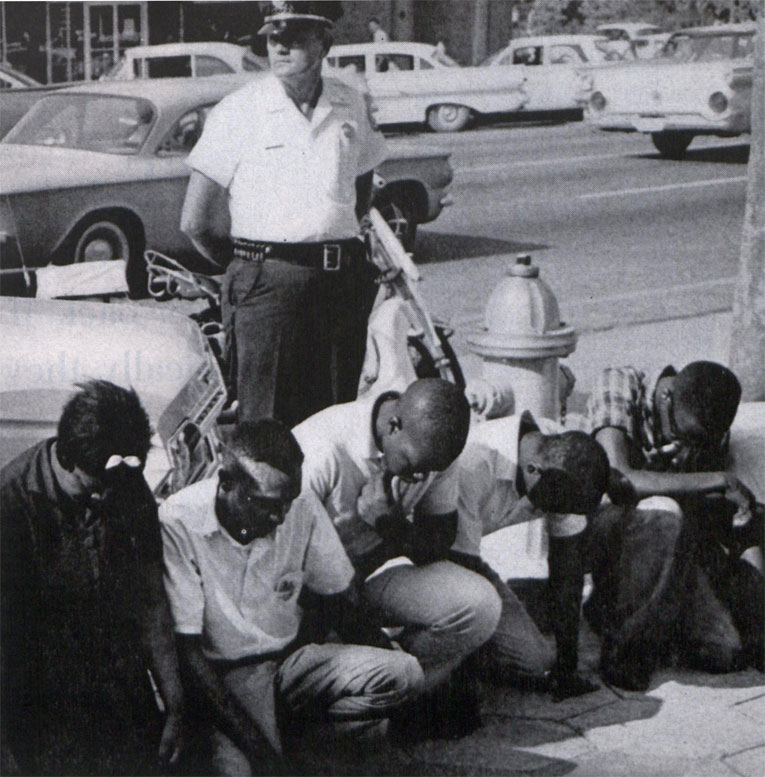

It began with the sit-in, a form of protest that had been sporadically used since the 1940s. The sit-ins were staged at the lunch counters of drug stores and ice cream parlors, where black men and women would take seats in areas reserved for whites only. They would ask for service and, of course, be refused. They would then remain in their seats, waiting to be served, until the store closed or they were arrested.

In February 1960, four students sat in the whites-only section of a lunch counter inside the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth’s store. They were refused service, as expected. When the store closed that night, they left peaceably. The next day they returned along with 16 more protestors, all of who were refused service. On the third day, 60 protestors showed up. On the fourth day, 300 protestors crowded into Woolworth’s to join the daily sit-in. White customers began avoiding the lunch counter and the store’s business declined. Eventually the store’s owners relented and ended segregated service. The first black customer at the Greensboro Woolworth’s was served on July 25, 1960.

1963 © SEPS

Bagdikian was impressed with the way the black community joined into this activism. In Orangeburg, South Carolina, for example, when students were refused service at a lunch counter, 25 other students from a local college protested. “When their college threatened to expel the students, 500 others marched downtown. When the city said it would arrest all demonstrators, 1,400 paraded silently on City Hall.”

By the first anniversary of the Greensboro sit-in, black protestors had staged 48,000 demonstrations in seven Southern states.

At the same time, a new campaign to help Southern blacks register to vote drew volunteers from across the country. Harvard doctoral student Robert Moses told Bagdikian, “I saw a picture in The New York Times of Negro college students ‘sitting in’ at a lunch counter in North Carolina. The students in that picture had a certain look on their faces—sort of sullen, angry, determined. Before, the Negro in the South had always looked on the defensive, cringing. This time they were taking the initiative. They were kids my age, and I knew this had something to do with my own life. It made me realize that for a long time I had been troubled by the problem of being a Negro and at the same time being an American. This was the answer.”

Moses, then a Ph.D. candidate at Harvard, was one of many black Americans heading south to coach Southern black voters on ways to pass their state’s registration tests. He wound up in Liberty, Mississippi, where 5,000 black voters lived but only one was registered to vote.

While he was committed to non-violent means, his opponents weren’t. On August 29, 1961, Bagdikian reported, “Moses was struck down by a cousin of the local sheriff and beaten on the head until his face and clothes were covered with blood.” A week later, one of his colleagues was kicked to semi-consciousness. A month later, another was shot dead.

The following year, black Americans made a further advance against segregated institutions. After a long fight in the courts, James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi, becoming its first black student. The night he arrived at the university, guarded by U.S. marshals, the campus exploded in a riot. More than 28 marshals were shot and 160 were injured. Two men, a student and a French reporter, were shot and killed, and 200 people were arrested.

But Meredith, like Moses, was undeterred by the violence. “In the past, the Negro has not been allowed to receive the education he needs. If this is the way it must be accomplished, and I believe it is, then it is not too high a price to pay.”

He believed he was working toward a future in which black Americans were fully integrated into society. In the past, he said, they had only regarded themselves, and their accomplishments, in relation to other blacks. “That’s not good enough. We have to see ourselves in the whole society. If America isn’t for everybody, it isn’t America.”

Coming Next: The Dangerous Doctor King