Douglas MacArthur: Controversial Hero

America has never been short of controversial figures. Our history is filled with characters that are both idolized and villainized. People who study the lives of Alexander Hamilton or Andrew Jackson often find it difficult to remain neutral about their careers.

Douglas MacArthur is a particularly good example of these controversial Americans. Born 130 years ago on January 26, MacArthur still inspires incredible devotion and harsh criticism. Any American who sparks such extreme opinion must represent something deep and valuable in the national character.

MacArthur had an extensive military career, to say the least. His military history began in 1903 when he graduated from West Point with honors. He served with distinction in the First World War, where he commanded the 84th Infantry Brigade. His soldiers were among the first to cross no-man’s land in the final advance into German-held territory.

By 1918 he was near the top ranks of the military, and was selected as the army chief of staff in 1930. The timing of this promotion was unfortunate due to the economics of the time and his efforts were mostly directed at preserving the military’s meager strength during the Great Depression. He retired from the US Army in 1937, only to be recalled to active duty in July 1941.

He is best known for his command of the Pacific Theater in World War II. After escaping from enemy encirclement in the Philippines in 1942, he directed the Allied forces that pushed the Japanese back across the Pacific, island by island. In 1945 he received the surrender of the Japanese Imperial forces and, until 1951, directed the allied occupation of Japan.

by Col. Sid Huff

September 8, 1951

When the Post published a series of articles about MacArthur in 1951, you would have been hard-pressed to find Americans not familiar with the man. He had commanded the first nine months of the Korean War on behalf of the United Nations forces. He had launched a decisive invasion on the Korean coast in the rear of North Korea’s army. His forces threw the communists back so decisively that a fearful Communist China launched a counterattack. President Truman ordered MacArthur to pull back American forces. MacArthur wanted to continue his advance and wage war in the style he knew best, without political complexities. He spoke out publicly against Truman’s decision, and Truman relieved him of command.

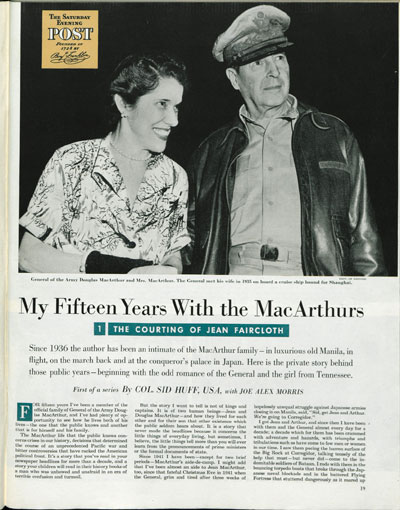

The Post published eight articles about MacArthur written by Col. Sid Huff, MacArthur’s aide for 15 years. The article presented a side of MacArthur not familiar to the American people. The series didn’t focus solely on his military leadership and war heroism, but also on his family, and the man “behind closed doors.”

In the first article from September 8, 1951, Huff talked about the General’s personal character. When asked by some if MacArthur was always the military man featured in the news and public, Huff responds,

“Actually the General is a very serious man who has been occupied for years with problems of grave import to America, and he so concentrates on what he is doing that there is little time left for any relaxation except the movies. He has no hobbies. He plays no games, such as golf or cards. He has no interest in ‘small talk.’ And he doesn’t enjoy meeting people merely for the sake of making new acquaintances. On the other hand, he has tremendous charm as well as a commanding, exciting personality; he can be tactful, gracious and even gallant, as the occasion commands, and he can and often does lean back in his favorite red-painted rocking chair and enjoys a real belly-laugh that makes the rafters ring.”

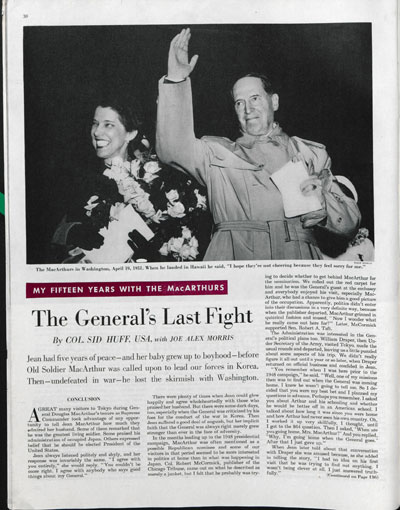

Huff describes MacArthur’s reaction to command being taken from him.

by Col. Sid Huff

October 27, 1951

“Anybody who knows MacArthur soon realizes that he is sensitive to criticism. In a way, this sensitivity is his Achilles’ heal… MacArthur was widely criticized — much of the criticism arising from political motives — and the more he was criticized the harder he worked. He directed a masterful retirement in Korea and he seemed in public to be as unaffected by the attacks made on him personally as he had been earlier by the lavish praise he received when he was winning. But in the lonely watches of the night it hurt. It hurt him so keenly that his staff did everything possible to protect him. We even hid newspapers and magazines from him if they contained particularly unrestrained criticism…”

When notified of being relieved his military command, Huff says, MacArthur responded, “without much change of expression or demeanor. He didn’t like it, but it was an order.” MacArthur did not drag his feet. He tied up the loose ends and returned to the US.”

Even beyond the articles featured in The Post in 1951, MacArthur lived out his days rather quietly. Other than chairing the Board for the Remington Rand Corporation, he lived his final years in New York City. He died in Washington, DC in 1964.

MacArthur’s critics cannot be dismissed; they point to the general’s arrogance and self-absorption, his short-sighted preparations in the Philippines, his readiness to promote a war with China, and his political posturing in the ’40s and ’50s. They also compare MacArthur’s performance with those of Generals Eisenhower and Marshall — men who achieved greater things without his posturing or recklessness.

Still, MacArthur was a powerful figure to Americans during the war years. He became a symbol of America’s strength and determination. He inspired devotion and confidence, both of which proved valuable to our success in the World War. Any man who draws such lasting admiration from so many Americans must represent something great about our country.

In the 1977 Saturday Evening Post article “More Than A Star,” Gregory Peck described his role as the general in the movie, “MacArthur.”

“I came to this role with a grab bag full of prejudices… Now I’m full of admiration for the man. His faults were on such a grand scale they’re too obvious to discuss. They weren’t petty. There was no meanness in him and most of the things that MacArthur detractors say are based on idiosyncrasies — his long hair, his corncob pipe, his informal dress. It was kind of inverse snobbism — never wearing any medals. It was the theatricality of knowing less is more. When he stood with generals and admirals, he stood out in his simplicity. He made them all look silly.”

Read The Courting of Jean Faircloth, published on September 8, 1951 [PDF].

Read The General’s Last Fight, published on October 27, 1951 [PDF].