Nudity, Fasting, and Eyelid Workouts: The Original Wellness Guru

One man you’ve never heard of is responsible for many of our notions about diet and exercise in America in the last 100 years. Though he was a largely-forgotten quirk of the turn of the century, many of his ideas about wellness have prevailed. Others — like his lifelong refusal to wear glasses — have depicted his movement as a too-natural health crusade.

Part Donald Trump, part Gwyneth Paltrow, and a tinge of Billy Graham. That was Bernarr Macfadden, the publisher, politician, and fitness fanatic born 150 years ago today.

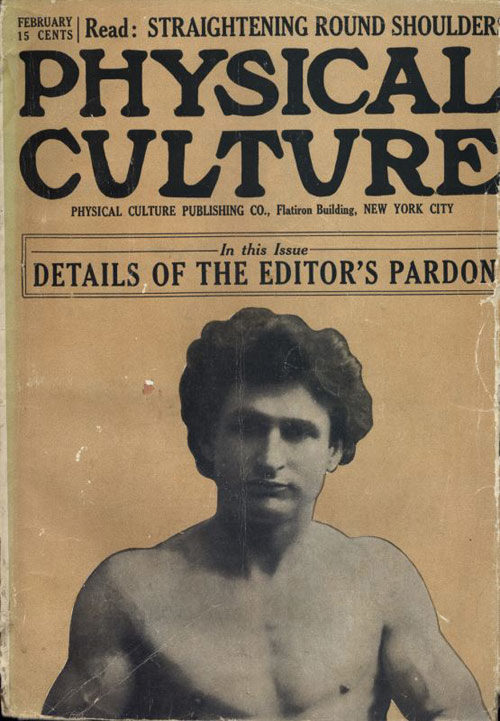

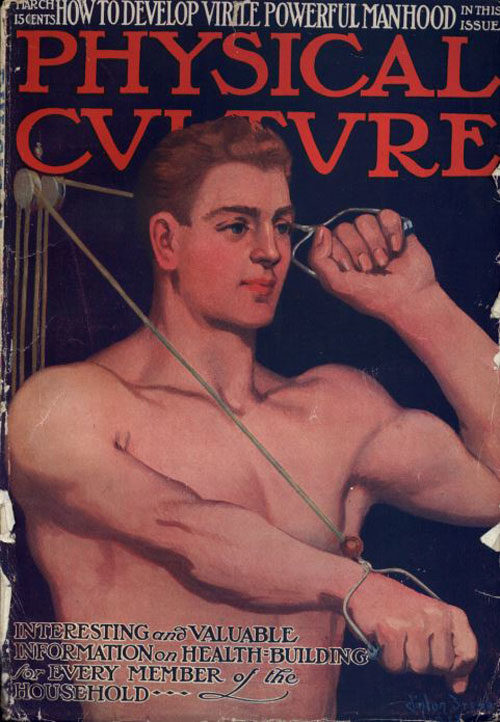

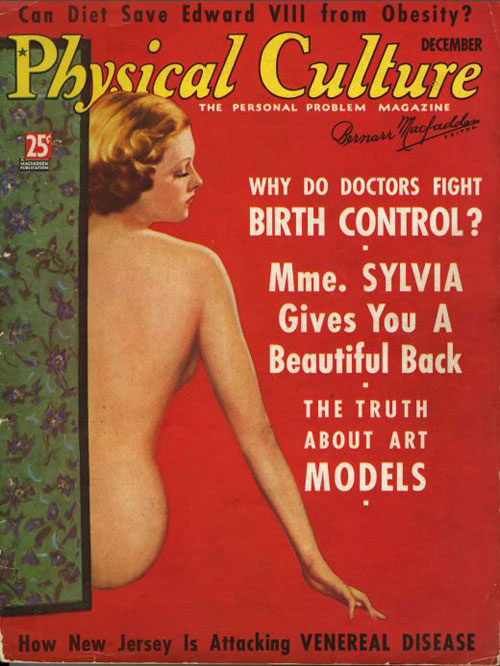

His legacy, the four-decades-published fitness magazine Physical Culture, proclaimed on its cover, “Weakness a Crime, Don’t Be a Criminal.” Early in his publishing career, Macfadden laid out the “curses of humanity” that he would fight until his last breath: prudishness, corsets, muscular inactivity, gluttony, drugs, and alcohol.

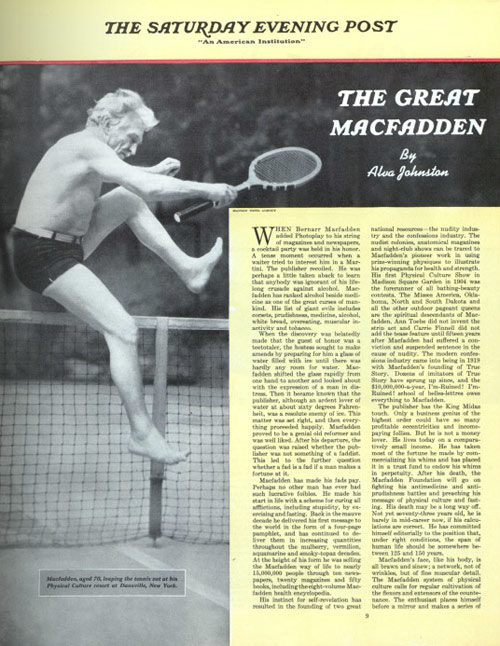

When The Saturday Evening Post profiled Macfadden, in 1941, the 72-year-old wack-of-all-trades was “all brawn and sinew” and running a magazine empire of his own with titles like True Story, Photoplay, and Liberty. It all started in 1899 with Physical Culture. The self-proclaimed “professor” of physicality started the publication in an office in Manhattan. He wrote guides for exercise and fasting and featured half-naked photographs of himself demonstrating his prescriptions.

His magazine’s circulation grew to hundreds of thousands in a few years as he proselytized — often under various pen names — about vegetarianism, antivaccination, bodybuilding, and even methods for better sex. Physical Culture was marketed to men and women, and Macfadden edited the rag with a unique philosophy of confessional honesty and reader interaction. Articles on “Straightening Round Shoulders” were followed by “Beauty Culture for the Hair,” and Macfadden’s always-candid editorials railed against white flour and prudery, especially if it came in the way of educating the masses frankly about their bodies.

The obscure American icon could best be characterized by his tendency to stick to his guns, even if it involved doubling down on wild, unsubstantiated claims. “Form your opinion upon a given subject and stick to it, argue it out, fight it out,” he wrote in the first issue, “and this opinion you take up will bring in its trend a wonderful flow of thought, of ideas. Whether these be right or wrong, it does not matter a jot.” Macfadden would argue for workers’ rights, temperance, and appreciation of the nude human form. Most of all, however, he asserted that modern medicine was worthless and that a healthy diet (and some intermittent fasting) could cure any disease imaginable.

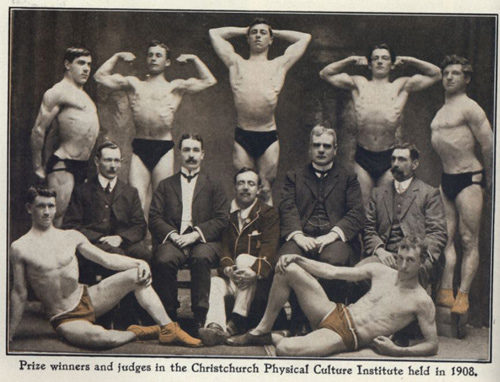

The recent migration of Americans from rural to urban surroundings generated all sorts of health complications and societal woes, and so Macfadden’s attempts to stoke a simpler, healthier lifestyle were well-received. In 1905, he opened Physical Culture City, a planned community in northern New Jersey where inhabitants could practice a lifestyle of fitness and clean eating with no red meat, no white bread, and no high-heeled shoes. The publisher had high hopes for his health utopia, but it hosted only a small, dedicated group, and nearby towns were freaked out by the village’s half-dressed, vegetarian populace.

In 1907, Macfadden was arrested for distributing “obscene, lewd, and lascivious” materials through the mail. It was a classic case of prudishness. Unlike most large publications of the time, Physical Culture prided itself in facing head-on issues of sexual health and depicting sexuality. “The exposure of ‘sexual affairs,’” Macfadden wrote, defending a recent serial, “was an essential step toward clean morals.” Still, he was sentenced to two years in the New Jersey Penitentiary and fined $2,000. He urged his readers to plead President Theodore Roosevelt, whose active lifestyle Physical Culture had commended, to commute his sentence, but it was fruitless. Instead, it was Roosevelt’s successor, hefty President Taft, who pardoned Macfadden and saved him from serving time.

The health nut took his affairs to Battle Creek, Michigan, where cereal magnates John Harvey Kellogg and C.W. Post had already built a wellness mecca. The Bernarr Macfadden Sanatorium offered hydropathy, osteopathy, milk diets, and other forms of alternative medicine in a stark mansion setting. Instead of committing to a rural planned community, clients could vacation in Macfadden’s house of Turkish baths and naturopathic doctors, and they did. Famed writer Upton Sinclair visited Macfadden’s facilities and published The Fasting Cure in 1911 in support of his friend’s homeopathic methods.

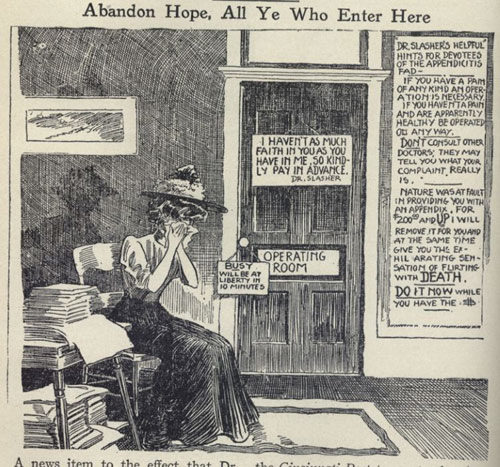

Macfadden moved the operation to Chicago after a few years and set to work finishing Macfadden’s Encyclopedia of Physical Culture, an ambitious collection of wellness knowledge in five volumes. His Encyclopedia documented many now-understood health habits and exercises far ahead of its time. Macfadden recommended whole grains, coconuts, and olive oil and condemned unnatural and processed foods. He also laid bare the fundamentals of sexual intercourse and clashed with modern understandings of microbiology. “The healthy, vigorous, athletic student here has no fear of disease; he is immune,” the Encyclopedia claims. “Unconsciously he lives in the recognition of a fact that the doctors and learned men have forgotten, that disease can find no lodgement in a healthy body.” Macfadden began a formal conflict with the medical establishment, namely the American Medical Association, that would last until the end of his long life.

In his dogged quest for a better way, Macfadden’s stubbornness and martyrdom served him well… until they didn’t. Eventually, after more obscenity trials prompted him to flee to Europe, Macfadden took up his businesses again, but over time his credibility shrank as scientific evidence countering many of his claims grew. Although he had been instrumental in making Americans interested in physical fitness (The YMCA’s attendance tripled in the first 10 years of his magazine), his bizarre advice for “natural” breathing and eyelid workouts seemed a less-viable sell toward the midcentury. Macfadden lost most of his fortune and died in relative obscurity, but his contributions to publishing (for better and for worse) and to alternative forms of medicine persist. His call for greater autonomy and responsibility for one’s wellness, however peculiar a practice may seem, is one that echoes through generations as if by human nature.