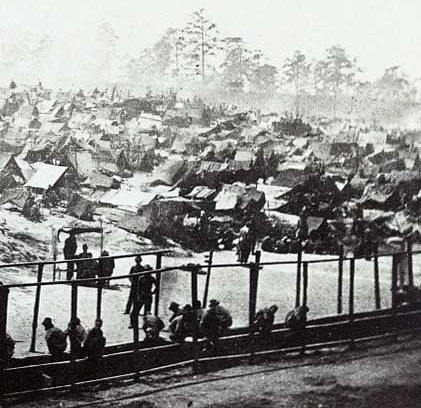

American Civil War Atrocity: The Andersonville Prison Camp

Of the 45,000 Union soldiers who’d been held at Andersonville Confederate prison during the American Civil War, 13,000 died. During the worst months, 100 men died each day from malnutrition, exposure to the elements, and communicable disease.

Restoring unity in America after the Civil War was never going to be easy. Too many Americans felt they could never forgive wrongs committed by the enemy during the conflict. Southerners could point to the destruction wrought by General Sherman’s army on its destructive march through Georgia and South Carolina. And Northerners could point to Andersonville.

This Confederate prisoner-of-war camp, which opened 150 years ago this week, was built in southeast Georgia to hold the Union prisoners who could no longer fit into Virginia’s prison camps.

Its stockade, in which prisoners were detained, measured 1,600 feet by 780 feet, and was designed to hold a maximum of 10,000 prisoners.

The prisoners arrived before the barracks were built and so lived with virtually no protection from the blistering Georgia sun or the long winter rains. Food rations were a small portion of raw corn or meat, which was often eaten uncooked because there was almost no wood for fires. The only water supply was a stream that first trickled through a Confederate army camp, then pooled to form a swamp inside the stockade. It provided the only source of water for drinking, bathing, cooking, and sewage. Under such unsanitary conditions, it wasn’t surprising when soldiers began dying in staggering numbers. The situation worsened as the camp became overcrowded. Within a few months, the population grew beyond the specified maximum of 10,000 to 32,000 prisoners.

After 15 months of operation, the camp was liberated in May of 1865. Of the 45,000 soldiers who’d been held at Andersonville, 13,000 died. During the worst months, over 100 men died each day.

News of the conditions at Andersonville came slowly to the North. The name wasn’t even mentioned in the Post until the following March, when the notices on page 7 announced the death of Robert Price “at Andersonville, Ga.…of chronic diarrhea.” A member of the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers, he “was taken prisoner by the rebels, May l5th, 1864” and managed to survive just three months in the camp.

As news of the death camp reached the newspapers, Northerners were newly enraged at the South and its army. Hearing of the miserable conditions and high death rate in the camp, Walt Whitman wrote, “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven, but this is not among them.”

Andersonville’s reputation was widely known when its name next appeared in the Post. In 1865, the Post’s front page featured a poem by Miss Phila H. Case, “In the Prison at Andersonville.” In this sentimental ballad, a narrator and his brother Ned are captured and shipped to Andersonville, where the brother soon sickens.

“He faded day by day—a prayer

Upon his lips for one sweet breath—

What wonder when the reeking air

Was chill and dank with dews of death.

But why delay my tale—he died

And careless hands bore him away,

For what was one when, side by side,

Hundreds were dying every day?”

In July, 1865, the Post reported “the former Rebel commandant [Jeff Davis] of the Andersonville prison is to be put on trial at Washington this week before a court-martial.” It adds no further comment, but an item just a few lines lower on the page reflects the bitterness many in the North were feeling. “Jeff Davis is reported, by the latest advices from Fortress Monroe, in the best of health and spirits.”

Many Northerners had expected the Federal government would hang the president of the Confederacy once he was caught after the war. But Davis, though indicted for treason, was never brought to trial. At the time the Post item above appeared, he was, in fact, living in leg irons and gravely ill. At the end of two years, the federal government released Davis on a bail of $100,000. The money was donated by Southern supporters as well as former Northern adversaries.

Andersonville’s commandant, Major Henry Wirz, didn’t fare quite as well. He was brought before a military tribunal in August of 1865 and charged with actions intended “to injure the health and destroy the lives of soldiers in the military service of the United States.” The court also charged him with murder “in violation of the laws and customs of war.”

There was no doubt Wirz allowed thousands of Union prisoners to die from exposure and malnutrition. Hundreds of ex-prisoners testified to his brutal punishments. But his defenders, both then and now, have offered several arguments in Wirz’s defense.

The federal government was partly to blame, they said, because it had halted its prisoner-exchange program.

By 1864, the Union army no longer believed it would win the war by a decisive strategic victory on the battlefield. It would have to win by attrition; that is, by wearing down the number of Confederate soldiers by death or capture until the Southern army could no longer fight. This strategy could work because the North had a greater population, and could replace the soldiers it lost, which the South couldn’t.

But the attrition strategy only worked if the Union refused to let its Southern prisoners return home and back into the Confederate army. In return, it meant Union prisoners would have to wait out the war, gathering in growing numbers in Southern prisons that barely had enough resources. However, the policy put a strain on Union camps as much as on those in the South.

Defenders of Wirz also point out the standards of hospitality were low in all prisoner-of-war camps. At the Union army’s camp at Rock Island, IL, for example, 1,300 Confederate soldiers died from an outbreak of smallpox. However, the Rock Island garrison eventually built barracks and a hospital to halt the smallpox epidemic. There were no similar improvements at Andersonville, where the death rate was four times higher than at Rock Island.

Others argued that the Confederacy couldn’t provide for its prisoners because it could barely provide for itself. The South was plagued by shortages because of the Union navy’s blockade of its coast, and the exorbitant costs of supporting its military, which left few resources for feeding or sheltering its prisoners.

These costs, however, were the unavoidable consequence of starting and continuing the war. Union soldiers had given themselves into the Confederacy’s care with the expectation of reasonable safety. Yet the soldiers who marched into Andersonville had less chance of emerging alive than the soldiers who marched onto the battlefield of Gettysburg.

The questions of guilt were troublesome. Obviously it took more than just Henry Wirz to make Andersonville possible. But once a court starts appointing guilt in wartime, it’s hard to tell where it ends.

In this case, it ended with the hanging of Major Wirz in November of 1865. The federal government was so reluctant to appoint blame that he became one of only three Confederates executed for their atrocities during the war.