True Grit vs. The Wild Bunch: The Week of Peak Western

They opened one week apart 50 years ago. One featured the matchless giant of the genre; the other came from one of its great directors. True Grit opened first, followed just seven days later by The Wild Bunch. These two films reflected different views of the Western, but also proved how versatile and durable the form could be in the right hands.

Charles Portis’s True Grit first saw light as a novel serialized in The Saturday Evening Post in 1968; the following year, it was adapted into a screenplay by Marguerite Roberts. John Wayne had campaigned for the lead role of Rooster Cogburn after reading the book, and championed Roberts as a writer despite her having been “blacklisted” during the Red Scare. Wayne would later recall the script as the best he’d ever read.

Wayne, of course, typified the Western genre in the American consciousness. Of the approximately 170 films he appeared in, over 80 of them were Westerns. Wayne was conservative politically and curated his reputation to the point where he declined to appear in the Western comedy film Blazing Saddles because he felt that the raunchy material went against his family-friendly image. That image actually made a for a good fit with the material of Grit, where Wayne’s cantankerous U.S. marshal develops a vaguely paternal relationship with young Mattie (played by Kim Darby), who hires him to track down her father’s killer.

The original trailer for True Grit (Uploaded to YouTube by Paramount Movies)

Despite pushing against the boundaries of the traditional Western by highlighting the fact that Cogburn is an aging protagonist, much of the plot fits within the confines of what people were expecting of the genre and Wayne. The curmudgeonly Cogburn is a decent and heroic man, as is the third member of his and Mattie’s group, Texas Ranger Le Boeuf (country star and occasional Beach Boy substitute Glen Campbell). Justice is served, evil is punished, and Mattie even promises to have Cogburn interred at her family plot when he dies. The film traffics in themes of “found family” as much as it does in the well-worn revenge and justice tropes of the Old West.

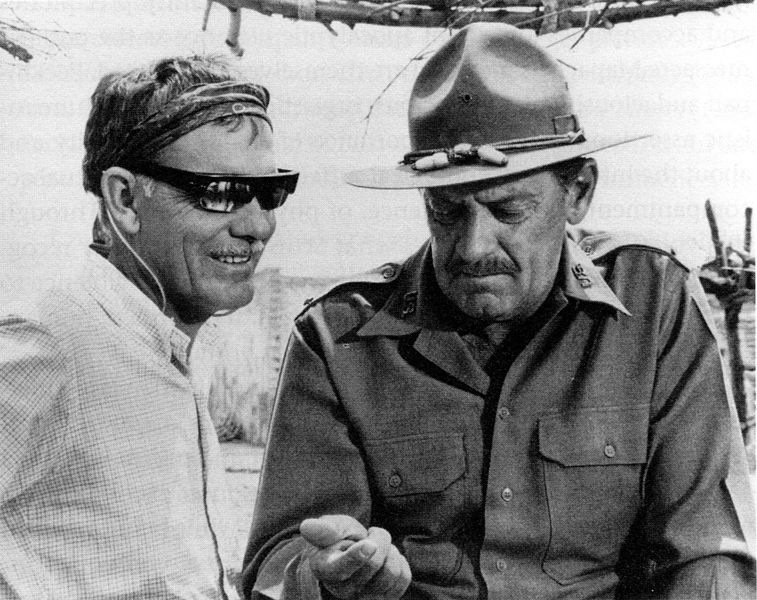

Released just one week later on June 18, 1969, The Wild Bunch leans into a very different sensibility. Directed by Sam Peckinpah, who rewrote the film from an original screenplay by Walon Green and Roy N. Sickner, The Wild Bunch captures the same ethos of the aging cowboy, but flips it from lawman to outlaw. The film taps into the idea of “honor among thieves,” challenging the audience to identify with a cast of hardened criminals while suggesting that they do indeed adhere to their own version of a code.

The original trailer for The Wild Bunch (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Bros.)

The overall plot of The Wild Bunch, which involves a group of outlaws (led by William Holden and Ernest Borgnine) chasing their last score, isn’t that unusual. Neither is the subplot of the group being pursued by a now-deputized former ally (played by Robert Ryan). What sets the story apart is the way in which the steady approach of the modern world is transforming the West. The characters are aging, and the country they knew is changing around them; they recognize their own mortality and the fact that they are, in a sense, outdated characters.

But the larger, and more shockingly revolutionary change, is the frank depiction of violence. Peckinpah leans into the brutality. His shoot-outs pull no punches. They are bloody, messy affairs that strip away the lie of the clean gunfights that filled earlier movies of the type. Civilians, including women and children, die in public crossfires. Bodies are riddled with bullets. And the blood doesn’t just flow; it bursts. This is the same frank depiction of violence that began in part with Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 and continued throughout Peckinpah’s own work, including Straw Dogs and Cross of Iron, signaling the beginning of what was called “the new Hollywood,” which placed a greater emphasis on realism and cinema as visceral experience.

The two films met with very different receptions. Wayne won both the Golden Globe and Academy Award for best actor for True Grit, while the title song (sung by Glen Campbell) was nominated for both distinctions, as well. The movie turned out to be a solid box-office performer, as well.

The Wild Bunch was instantly polarizing; the late critic Roger Ebert recalled that, at the initial screening, he stood to defend the film against an attack from the critic for Reader’s Digest, who had questioned why such a film had even been made. A number of prominent critics did praise The Wild Bunch, including Vincent Canby of The New York Times; Time also weighed in with positive notices, offering unabashed praise of Holden and Ryan and going on to state that “[the film’s] accomplishments are more than sufficient to confirm that Peckinpah, along with Stanley Kubrick and Arthur Penn, belongs with the best of the newer generation of American filmmakers.”

One person that wasn’t a fan of The Wild Bunch was, perhaps unsurprisingly, John Wayne. Wayne noted privately and in interviews that he felt that that film destroyed the myth of the Old West. The actor commented on Clint Eastwood’s similarly nihilistic High Plains Drifter in 1973; in a 1993 interview with Premiere magazine, Eastwood recalled that Wayne wrote him directly and said, “That isn’t what the West was all about. That isn’t the American people who settled this country.”

Over the years, True Grit continued to be held in high esteem, while The Wild Bunch grew in reputation among critics and film scholars. Peckinpah’s command of violent action and quick editing can be seen today in the work of directors like John Woo and Quentin Tarantino. True Grit received an acclaimed remake in 2010, while The Wild Bunch has managed to avoid multiple efforts at a new version. It’s fair to say that Bunch helped usher in the age of the revisionist Western, seen in films like Unforgiven that take a more unflinching look at consequence of violence. It’s perhaps strange that two genre classics that were so different from one another were released in the same week, but it did seem to mark a tidal shift when the narratives of American film grew darker and the myth of the American West began to be resigned to just that: a myth.