The Argument: Should America Reinstate the Draft?

YES

The draft would compel us to share the sacrifice.

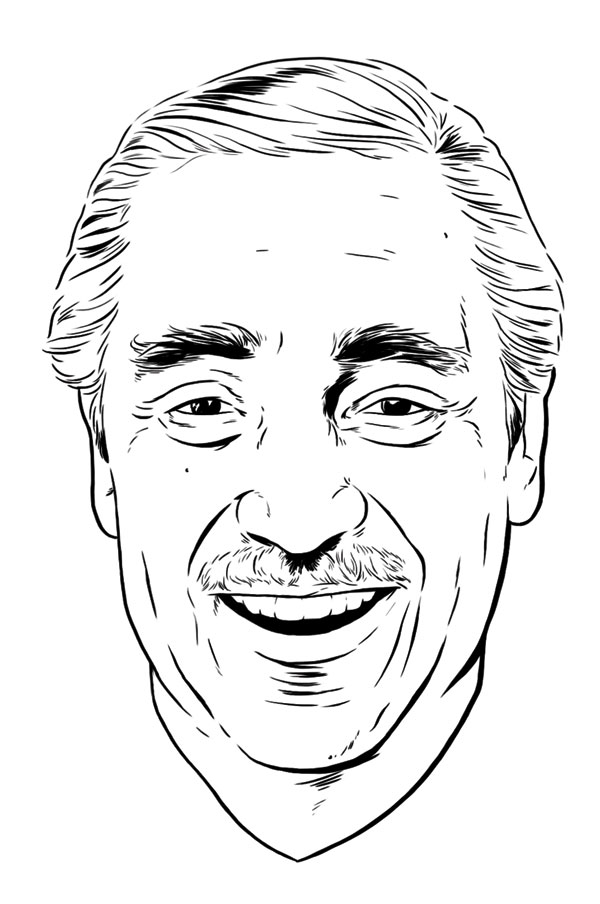

by Congressman Charles Rangel

On a freezing night in November of 1950, I found myself and dozens of fellow soldiers marching along the icy banks of the Ch’ongch’on River amid the cracks of mortar fire and the glints of Chinese bayonets. The war in Korea was in full force, and my battalion was retreating because our vehicle column had sustained an attack. After a three-day nightmarish trek through enemy territory, 40 of us escaped. In the battles around Kunu-ri, more than 5,000 American soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured. Ninety percent of my unit was killed.

When we returned home, many of my comrades were haunted by memories of their combat experience. They were consumed with guilt, couldn’t sleep or function in their jobs, and became severely depressed. In short, they developed “shell shock,” or what today we call post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD. Following the lead of generations of soldiers, most of them suffered in silence, did not seek treatment, and never got better.

Today, we have the awareness and the resources to protect our troops from PTSD. We now know that prolonged exposure to combat is a primary cause of this affliction. A 2008 Army Surgeon General’s study confirmed that more tours of duty mean a greater risk of PTSD for soldiers. Twelve percent of soldiers on their first deployment suffer mental health problems, compared to 27 percent of those on their third and fourth tours. Moreover, suicide rates among veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars are approximately three times higher than in the general population. Yet we subject our troops to more cumulative months of combat than ever before, with shorter rest periods in between.

During Vietnam, almost no Americans were required to serve more than a single tour of duty overseas, although some volunteered for more. In Iraq and Afghanistan, however, nearly half of all soldiers are sent on multiple combat tours—sometimes as many as four. These are separated by reprieves that constantly shift in length, but are always too short to allow for substantive mental health treatment.

This is the inevitable result of having less than one percent of our population carry the burden of war for the remaining 99 percent. More than 15 million registered for the Selective Service System; only 1.4 million are on active duty. This explains why 300,000 veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars—nearly 20 percent of the returning forces—suffer from PTSD or major depression. It is not fair or morally defensible to saddle the brave Americans who volunteer for the Armed Forces with tours of duty that expand in length and frequency as our conflicts intensify.

As a nation we should ask ourselves how we can protect our troops’ mental health while maintaining our national defense. Two years of civil service from all U.S. residents would allow us to meet both of these goals. Our military ranks would swell and there would be no need to demand repeated service from our troops. That is why I continue to call for Universal National Service, which would mandate a two-year service requirement for Americans ages 18 to 25. While my “draft” bill is unlikely to become law, it is important that we open a national conversation about how we can all share in the sacrifice for our country.

Requiring two years of service from everyone would compel us to rethink how and why we send young Americans into harm’s way. Too few of the country’s leaders have a personal stake in the well-being of the Armed Forces, and the outcome is predictable. Since the end of the draft in 1973, every president, Democrat and Republican alike, has approached warfare with the mind-set of invading, occupying, and expanding our nation’s influence. It was this attitude that got us into the unnecessary and costly wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and that threatens to mire us in deadly wars in the future. We make decisions about war without worry over who fights them. Those who do the fighting have no choice; when the flag goes up, they salute and follow orders.

A universal service mandate would do more than deter future military entanglements. As shown in a report by the Congressional Budget Office, most of our volunteer troops come from economically depressed urban and rural areas. We have developed, in effect, a mercenary army. In New York City, an overwhelming majority of volunteers are black or Hispanic, recruited from lower income communities such as the South Bronx, East New York, and Long Island City. These enlistees are enticed by bonuses up to $40,000 and thousands in educational benefits.

Military service is a privilege, and it should not be shouldered only by those for whom the economic benefits justify great personal risk. If young men and women of all races and socioeconomic statuses served together, our citizens would come to share or at least understand one another’s values, points of view, and beliefs. Empathy and mutual respect would provide a much-needed antidote to the cynicism that today’s youth feel because of the extreme partisanship in Washington.

A universal national service requirement, even if it does not mandate enlistment in the Armed Forces, is the one mechanism we know will truly protect our troops, unify the nation, and bring fairness to our military. Furthermore, it will season our future leaders with the harrowing realities of war, ensuring that they will never commit our troops to the battlefield unless they are willing to send their own children.

Charles Rangel has served 43 years as a Congressman from the 15th district in New York City. He is the ranking Democrat on the House Ways and Means Committee and serves on the Joint Committee on Taxation.

View the next page to read defense expert James Lacey’s argument.