8 Things You Didn’t Know About the Marines

The phrase “The United States Marine Corps” immediately conjures a number of images and ideas. Toughness. Honor. Tradition. And while that reputation can be traced back to 1775, the “Act for establishing and organizing a Marine Corps” was signed by President John Adams on this date, July 11, in 1798. On its 220th anniversary, we look some of the longstanding traditions that make the Marines the Marines. Some are reflected in the modern culture of this military branch, while others are just downright peculiar.

1. The Marines Have Two Birthdays

The modern Marine Corps descended from the Continental Marines assembled under the Continental Marine Act of 1775, which was initiated by the 2nd Continental Congress on November 10th of that year. Though the Continental Marines were disbanded at the end of the Revolution, the United States Marine Corps still commemorates November 10th as their official creation.

The Marines were “reborn” in 1798. The creation of the United States Navy and Marine Corps grew out of clashes with the French navy during the French Revolutionary Wars. An act of Congress formed the Navy in 1794, with Marines recruited to serve on newly created ships by 1797. Adams signed the “Act for establishing and organizing a Marine Corps,” authorizing a battalion of 500 privates along with a major and other officers. Revolutionary War veteran William Ward Burrows was made an initial major. Marines would serve in the Quasi-War, that undeclared war between the new French Republic and young United States that occurred between 1798 and 1800.

2. Why the Marines are “Marines”

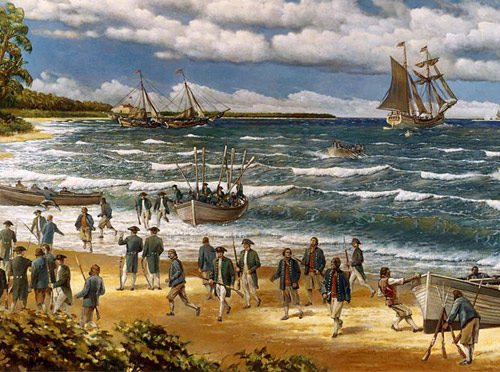

The term Marine came from the type of infantry that supports naval operations. The Marines of the American Revolution typically mounted amphibious assaults, landing from tall ships to conduct raids in locations like British ports in the Bahamas. During the Barbary Wars against piracy that ran from 1800 to 1815, Marines frequently fought in ship-to-ship battles, boarding vessels to capture them.

3. Thomas Jefferson Chose the D.C. Barracks Site

In 1801, President Thomas Jefferson and Burrows, now Lieutenant Colonel Commandant of the Marine Corps, chose the site of the Marine Barracks in Washington, D.C. A National Historic Landmark, it is still in use today as the official residence of the Commandant, the home of the U.S. Marine Drum and Bugle Corps, and the main ceremonial location for the Corps.

4. The Dress Blues Were Overstock

Sometimes a uniform is carefully designed and thought out over time. And sometimes, you take what you can get. The familiar ceremonial “dress blues” of the Corps adopted their look from an overstock of blue jackets with red trim that Burrows received upon his original appointment to major.

5. The First Marine Sword Was a Gift

While battling Barbary pirates in Africa, First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, eight other Marines, and over 300 mercenaries of Arab and European origin mounted an assault on Tripoli in an attempt to liberate the captured crew of the U.S.S. Philadelphia. Though they did not take the city, deposed Prince Hamet Karamanli allegedly presented a Mameluke sword to O’Bannon after the Battle of Derna. The sword story sparked the tradition of Marine officers wearing swords in dress blues.

6. Why Tripoli Is in the Marine Hymn

The other lasting legacy of the action was the inclusion of the lyrics “to the shores of Tripoli” in the Marines’ Hymn by Thomas Holcomb in 1942. The Hymn is the oldest of any of the songs that represent the U.S. Armed Forces. The original music was written in 1867 by Jacques Offenbach, but it wasn’t adopted as the official music of the Corps until 1929.

7. There Are a Lot of Active Marines

Today, the USMC boasts 186,000 active Marines with around 38,500 reserves. Roughly 7.6% of today’s Marines are women. Of the more than 22 million veterans living in the United States as of 2014, less than 1% were Marines.

8. They Perform MANY Jobs

Over 336 MOS (military operational specialist) codes, or job types, are presently available in the Marines; paths include everything from infantry to avionics to 60 different categories of linguistics. Even as new avenues for duty continue to expand, it’s safe to say that, even after more than 200 years, the Marines continue to pursue high standards in their service to the country.

A Turning Point in the Solomons

But in early August, the U.S. began its offensive in the Solomon Islands, northeast of Australia. On the morning of August 7, 1942, the U.S. Marines made their first amphibious landing in 44 years at Guadalcanal.

The Japanese had landed on the island in June and started building an airfield.

When completed, it would enable their bombers to push the U.S. and Australia out of the Solomons and even strike the Australian mainland.

Samuel Eliot Morison was the official naval historian at the time, and had already begun writing the complete naval history of World War II. By the time he finished his 15-volume account, he had studied every naval engagement of the war. This is what he said about Guadalcanal in an article written on July 28, 1962, in the Post:

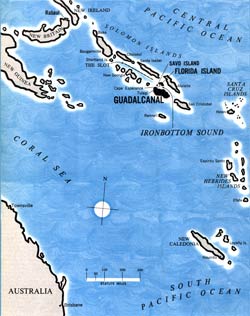

“You may search the seven seas in vain for an ocean graveyard with the wrecks of so many ships and the bones of so many sailors as that body of water between Guadalcanal, Savo and Florida islands which our bluejackets called Ironbottom Sound.

“There is something sinister and depressing about that Sound. [The marines] who rounded Cape Esperance in the darkness before dawn on 7 August remembered, ‘it gave you the creeps.’ Even the land smell failed to cheer sailors who had been long at sea; Guadalcanal gave out a rank, heavy stench of mud, slime, and jungle. And the serrated cone of Savo Island looked as sinister as the crest of a giant dinosaur emerging from the ocean depths.”

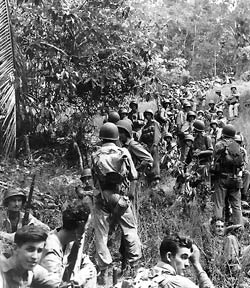

The U.S. forces were understandably intimidated. “The Japanese army in Malaya, the Philippines, and Java had acquired a reputation of invincibility, especially in jungle fighting, and its losses so far were minute. Their navy, despite its defeat at Midway, still had plenty of ships and planes to throw into the Solomons.” Fortunately, the Marine landing at Guadalcanal and neighboring Tulagi went well. By 4:00 PM, they had seized the unfinished airfield.

“Things looked very bright for the Expeditionary Force. Then, shortly after midnight, [began] the worst defeat in a fair fight ever inflicted on the United States Navy.” A Japanese task force of seven cruisers and one destroyer descended upon the Expeditionary Force, shot up the landing craft, and left the Marines without their naval supply line. Proceeding on to Savo island, they attacked first the Australian, then the American ships. Miscommunication, bad luck, poor judgment, and the element of surprise combined to give the Japanese a sizeable victory.

“It was not a decisive battle and not an unprofitable defeat,” wrote Morison, “although the cost was heavy—four heavy cruisers and one destroyer a total loss; 1270 officers and men killed and 709 wounded. … The Navy held an investigation, which found the blame so evenly distributed that nobody was punished. And it is well that Admiral Turner, primarily to blame, was not put ‘on the beach,’ because he became the leading practitioner of amphibious warfare in the Pacific. Many lessons were learned from this disastrous battle.”

As so often before, America’s entry into the war was marked by costly mistakes. Not being a warrior nation, we start each conflict with a civilian attitude and a reliance on what worked in the last war, and we are handed defeats. Fortunately, the American military always learns from these mistakes.

Over the next three months, American forces were able to hold their own in a costly standoff. “From sunup to sundown the Americans ruled the waves, big ships discharged cargoes, small ones plied between Lunga Point and Tulagi, as safely as in New York Harbor. But as the pall of night fell over the sound the Japanese took over. Allied ships cleared out like frightened children running past a graveyard, and small craft sought shelter. The ‘Tokyo Express’ of troop-carrying destroyers dashed in to discharge soldiers and supplies … and big ships tossed shells in the Marines’ direction. But the Rising Sun flag never stayed to greet its namesake; by dawn the Japanese were well away and the Stars and Stripes reappeared. Such was the pattern. … Any attempt to reshape it meant a bloody battle.”

At night, the Marines threw back repeated suicide attacks by the Japanese garrison. In the morning, Army engineers began to repair the bombing damage to Henderson airfield so vital supplies could be flown in.

“Ship losses were fairly balanced; two American light cruisers and four destroyers against two Japanese destroyers and a battleship. … But the enemy bombardment mission was completely frustrated.”

America didn’t know it was a turning point in the war. Military planners worried that every island battle across the Pacific would be just as long and bloody. But in 1962, Morison could point to Guadalcanal as “a definite shift of America from defensive to offensive, and of Japan in the opposite direction. Fortune now, for the first time, smiled on the Allies everywhere: not only here but in North Africa, at Stalingrad, and in Papua.”

Credit for victory in the Solomons should be given to over 80,000 Allied soldiers who fought there, and especially the 10,000 who died. But just as valuable as their fierce devotion and sacrifice was America’s readiness to learn from mistakes, to bring in better commanders, and to continue fighting when the grim price seemed too high. It was this spirit that prompted Winston Churchill to say, in 1942, “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”