Marjory Stoneman Douglas and The Saturday Evening Post

Today, Marjory Stoneman Douglas’s name is most recognized as the name of the high school where 17 people were murdered by a gunman. But her legacy deserves more than this notorious footnote. Douglas was a leading conservationist in her time, playing a major role in preserving the Everglades. Her life tells a story of creativity, compassion, and persistence.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas (1890-1998) was a formidable figure in the Florida landscape during her 108-year life, working as an advocate for women’s suffrage, civil rights, and conservation. She spent the first part of her career as a journalist, the middle part as a freelancer writer, and the latter part as an advocate for preserving Florida’s ecosystems. At age 79, she founded Friends of the Everglades, proving that it’s never too late to get involved. The petite but forceful woman was fond of sherry, pearls, and putting politicians in their place. But that’s not why the editors at The Saturday Evening Post knew her.

Douglas and The Saturday Evening Post intersected during the middle portion of her life, after she had left her position as an assistant editor at The Miami Herald in 1923 and decided to take up writing short fiction. The Post gave her a platform, publishing 38 of her short stories between 1924 and 1941. Douglas’ fiction was often about Florida and the quirky people who inhabited it.

Her first story for the Post was “At Home on the Marcel Waves,” published June 14, 1924. In the story, Augusta, a 6-foot-tall no-nonsense woman of the seas, comes to town and saves not only a beauty salon but the frail proprietress who runs it. The salon owner gazes with wonder at Augusta getting undressed and marvels that “only that morning she would have been ashamed to look at a bare-naked woman. Now she had to confess that it was sort of beautiful. But then, one looked at these things differently in Florida.”

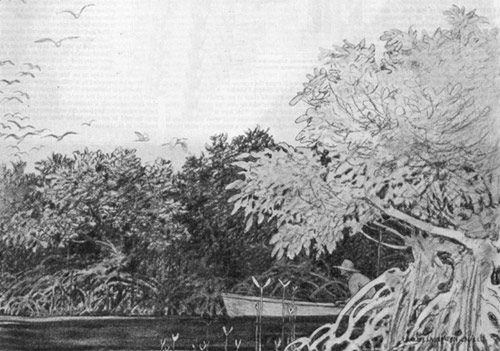

Many of her stories took place in the damp and snake-filled Florida wetlands. The Post published “Plumes” in 1930, which told the story of a game warden who was murdered by egret poachers. Of one of the emotionally stunted poachers — an escaped convict — Douglas writes, “He might not have, he could not possibly allow himself to have, any sort of emotion beyond the extremes of constant watchfulness, of constant caution, beyond a silent, aloof, moment-by-moment hoarding of the immense fact of freedom.”

In “Pineland,” a reporter drives home a woman whose son had just been hanged. Along the way, he learns her story of perseverance in the glades of southern Florida: “Staring at her he saw what it was really to be a pioneer, a woman, lonely, afraid of snakes, sustained by no dream of empire, but only by a six-shooter and the enduring force of her own will.”

Douglas also published a few nonfiction articles in the Post. In the December 25, 1931, issue, she profiled Dr. Frank A. Perret, one of the world’s great volcanologists, who lived on Martinique and studied the imposing, deadly volcano Pelée. (For his upcoming 70th birthday party, he planned to invite all 700 children on the island.) In “Wings,” (which, coincidentally, is the name of our feature story in our most recent issue), she wrote about the decimation of egrets in Florida’s wetlands.

Sixteen years later, Douglas would publish what is considered a classic in environmental literature, The Everglades: River of Grass, which is said to have had as much impact on environmentalism as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring.

As if she weren’t busy enough, Douglas was also involved in women’s suffrage, slum improvement, the ACLU (as a charter member), the Equal Rights Amendment, the protection of migrant workers, and support of local public libraries. At 79, she founded Friends of the Everglades to stop the construction of a jetport. They convinced the Nixon administration to pull funding, and the project was halted. Her advice was, “Be a nuisance where it counts. … Do your part to inform and stimulate the public to join your action. Be depressed, discouraged, and disappointed at failure and the disheartening effects of ignorance, greed, corruption, and bad politics — but never give up.”

She is a reminder that you can take up a cause that can change the world, no matter your age.