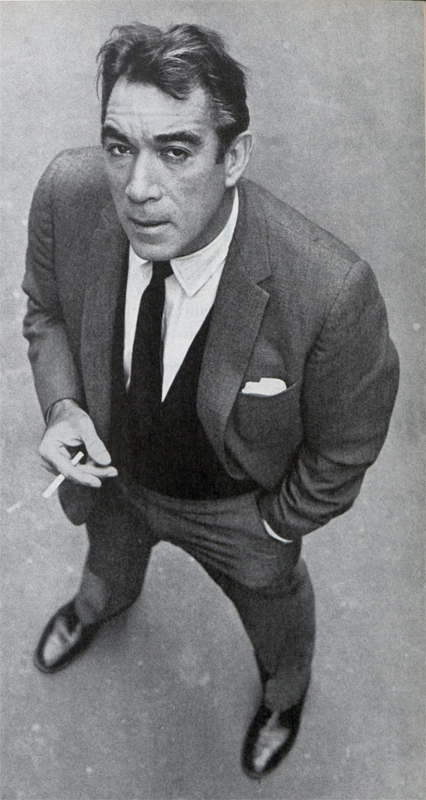

Leading Men of Hollywood: Marlon Brando

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood. This edition can be ordered here.

Before us, a crack, about half as wide as our car opened in the track. At the wheel beside me, Marlon Brando aimed the nose of his car at the opening. He shoved his foot down hard on the accelerator. My stomach flipped convulsively. I shut my eyes, then opened them. e crack widened in the split second before we bored into it. On each side of us frantic drivers jerked fenders out of our way.

As we hurtled through the opening, Brando put his head out. With contempt he said one word, “Toad!” to the driver on our left. He said it in a soft mumble. But it carried clearly.

As Hollywood interviews go, I thought, this one is going to be different.

I should have known from the beginning: that he didn’t mean what the usual dweller in Hollywood means when he says “to the beach.” Preparatory to creeping up on him, I had studied him from afar. My research had indicated that he is a nonconformist and endowed with a genius for the unexpected. He’d brought neighbors out of their beds at midnight because he’d chosen that hour to pound his African drums. Meeting a movie producer he had made up his mind in advance not to like, he’d held a fresh-laid egg in his hand while the producer shook it vigorously.

Paradoxically — and this makes him even more difficult to pigeonhole — when it comes to sad scenes on the screen, he is a four-handkerchief sentimentalist. Throughout a showing of THE YEARLING, he oozed tears. During a screening of THE WIZARD OF OZ, he wept copiously at the touching spots. Not having a handkerchief with him, he’d wiped his tears away on the face of the girl he was dating.

Despite such quirks, I was stupid enough to think that he would accept the Hollywood concept of “the really basic things.” What else could “to the beach” mean but a Malibu chalet, complete with picture windows, sun furniture and chafing-dish planters sprouting exotic plants? As for transportation, studios saw to it that you were rolled to keep an appointment with one of their stars in one of their long, purring limousines. Failing this, Brando would surely take me to the place appointed for our interview in his racy British sports roadster. As all the world knows, Hollywood stars come equipped with one of these at birth.

But I discovered that when Brando said “to the beach,” he meant just that. “I know a place where we can be alone,” he’d told me. “It’s 20 miles up the coast. Nothing but sand. We can sit there and talk while gulls hover overhead and pelicans dive — whoom! — for fish.”

As we headed in the direction of Santa Monica by way of Venice, Brando announced to me, “Back East the rocks are gray, dripping things. I don’t like the geology there. I haven’t yet found a place I’d like to live. Maybe around the Sault Sainte Marie Canal, where they’ve got big pine trees.”

We zoomed past Malibu. en past Los Tunas beach. Brando peered out as if looking for something. Then he found it. It was a side road leading behind a row of modest beach homes and running parallel to a stretch of sand bordering the Pacific. Stepping out of his car, Brando pulled off a T-shirt and dropped it on the front seat. He stepped out of his trousers—revealing faded swim trunks—and discarded his sneakers. I took my own shirt off and started to remove my slacks. Then I thought better of it. There’s no point letting the California sun have its merry way with me, I thought. Cooking my back, chest and shoulders is enough to pay for one interview.

I picked up my briefcase, and we walked toward the water. Our bare feet squirted sand under our heels. I sat down and took a notebook and pencils out of my briefcase.

“I make a mistake in talking to anybody,” Brando said, eying my preparations warily. “What I have to say is either misinterpreted or misunderstood, and I always feel betrayed afterward. But I’m building up armor against this sort of thing,” he went on defiantly, “so they can’t hurt me anymore.” By “they” it was obvious that he meant people like me. He didn’t say it with conviction. Nor did it take much insight to see that the bruises left by previous interviewers still hurt.

Rumor Versus Reality

I took a sheaf of notes from my briefcase. They were jottings of statements made about him, quotations of remarks he was supposed to have made. I handed them to him, gave him a pencil and asked him to correct the ones he found inaccurate.

He brooded over them darkly. “It says here that I’m a ‘brilliant brat’; that I’m ‘rude, moody, sloppy, prodigal’; that I’m ‘part child, part genius’; that I’m ‘an unhousebroken harlequin.’ They also complain that I scratch myself like a monkey. If it’s rude to scratch when you itch, then I don’t want to bless the world with my presence,” he said, scratching himself.

“I wouldn’t mind if people made up clever things about me. They’re too lazy to do that. Most columnists don’t get a chance to talk to me, but since I’m a semipublic figure, they feel they have to write something about me anyhow.”

He studied the notes I’d handed him for a while, frowned, muttered and worked on them with a pencil. Then he gave them back to me. I found myself frowning and muttering over them too. Brando’s spelling was even more off beat than Brando.

One of the statements I’d attributed to him read: “He has vowed never to become a slave to Hollywood, a community he finds vicious, degrading, disgusting and degenerate.” He’d crossed that out and had written in the margin: “You can find this sort of thing anywhere in the world, but Hollywood somehow acts as a firtertizer for it.” I pondered this for several minutes before I decoded “firtertizer.” He’d meant fertilizer.

Another one of the many press statements I’d given him to read over ran something like this: “Brando has a Mexican girlfriend. He met her in Mexico while readying himself for his part in VIVA ZAPATA! He may marry the girl. He says he definitely wants to marry somebody sometime.” When he returned it to me, he had crossed this out. In its place he had written: “Nobody’s biasness.”

Later, Brando remarked that he is really the opposite of the young brute he played in STREETCAR. “I despise that kind of human being,” he told me. “I think the reason I was a success in the film version of the play was that during the two years I spent on Broadway in the part, I’d developed a special characterization for it. It is impossible to do this for the usual film. You don’t even have time to rehearse properly.

“I invented a garbled way of talking for it I felt suited the character. When the critics hear me say Shakespeare’s words understandably, they’ll say I’m taking on hoity-toity airs. No matter what kind of delivery I use, the critics will nudge me with a broom handle.”

He said that once during the filming of STREETCAR he’d purposely got drunk to see if it would help him live his part more realistically. “Why not?” he asked. “After all, the character I was playing was half boiled most of the time. But I was so much under the weather I couldn’t act, and they had to sober me up and shoot the scene all over again.”

I gathered up my notes, pencils and briefcase, and we went back to the car. “I’ll drop you at your hotel,” Brando said. I had spent the afternoon trying to be a character analyst, and I realized I’d flunked the assignment. I couldn’t wrap Brando up into a neat bundle. I’d listened to him talk about what he thought of life, letters and being an actor. But what he’d told me rattled around in my mind confusingly.

There was one thing I could be sure of. Brando is the most outstanding male personality to hit Hollywood in many a year. An actor can act his head off, but if he has no spark, he might as well drop dead. Brando gives off sparks in showers. I found myself liking him despite the chip he wore on each shoulder. But I was glad I didn’t handle his public relations. That way lay stomach ulcers. I was even happier that I didn’t have to make a cross-country auto trip with him. I know truck drivers who take active measures when called a “toad.”

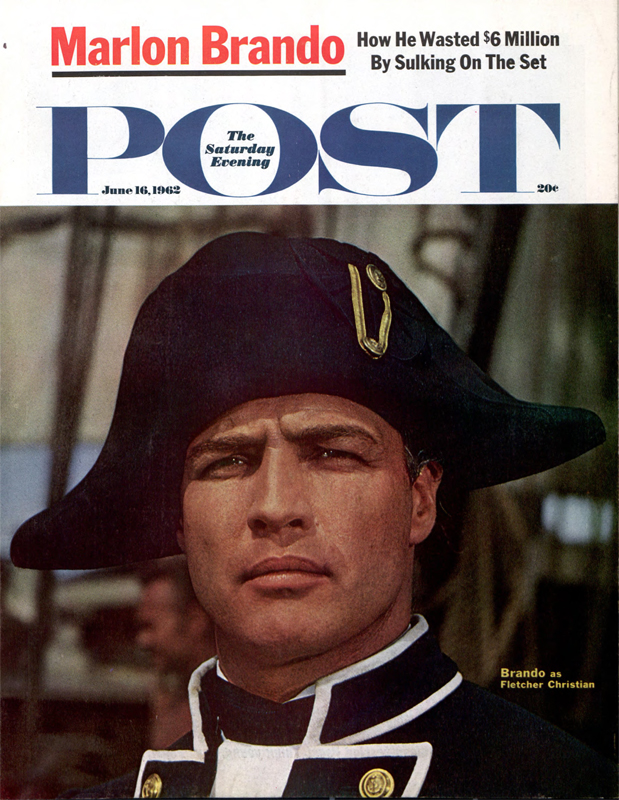

Bad Boys of Hollywood, 1962

Fifty years ago, the Academy Awards ceremony was handing out its Oscars to a remarkable crop of films—including big winners such as Lawrence of Arabia, The Miracle Worker, and To Kill A Mockingbird. Although Hollywood’s big-name actors were noted for memorable performances, several 1962 Post articles also pointed out that they were showing a trend toward rebellious, temperamental, and selfish behavior.

Rising stars like Anthony Quinn, Marlon Brando, and Peter O’Toole were becoming increasingly hard to work with, and were threatening the survival of the studios.

For example, an article about Anthony Quinn often described the actor as “volatile, unpredictable,” alternately gracious or bitter. A director, who had recently worked with Quinn in the movie Requiem for a Heavyweight, said, “I found Tony has great selfishness as a performer. He thinks how each scene can best serve him. Of course, when he’s good, he’s brilliant. He just makes it hard as hell for everyone around him,” [“Anthony Quinn, Unsettled,” October 13, 1962].

An article about Peter O’Toole, star of Lawrence of Arabia, mentioned the rumors among actors that O’Toole was brash, irresponsible, a braggart, and a drinker. The producer of Lawrence of Arabia believed the rumors, O’Toole said. “It hardly helped matters when a fifth of whiskey tumbled from my pocket during our first meeting,” [“Oscar Winner,” March 9, 1963].

Fellow Brit Richard Burton was becoming well known for his wild rages. While filming The Robe, he deliberately ran his head into a wall after failing to perform a stunt called for by the script. The year before, while performing in the Shakespeare festival at Stratford, “he got so carried away during a fight scene that he lifted [Michael] Redgrave and hurled him against the scenery, nearly bringing the set crashing down,” [“Actor With Two Lives,” January 27, 1962].

Robert Mitchum, who had just finished Cape Fear with Gregory Peck, instinctively fought any type of authority. His impatience often led him to lose his temper. When a studio phone failed to work, he destroyed his dressing room and walked onto the set to announce, “If they treat me like an animal, I’ll behave like an animal,” [“The Many Moods of Robert Mitchum,” August 25, 1962].

Newcomer Warren Beatty had starred in only three movies by 1962, but he was already making demands on the studio. He insisted on complete silence on the set while he was acting. He also demanded, and was given, the best dressing room on the lot, normally reserved for Gregory Peck, [“Brash and Rumpled Star,” July 14, 1962].

But of all the troublesome actors, none was more difficult or demanding than Marlon Brando. Lewis Milestone, who had recently completed Mutiny On The Bounty, told Post contributor Bill Davidson that Brando’s attitude—argumentative, uncooperative, and easily offended—“cost the production at least $6 million and months of extra work.”

Co-star Trevor Howard said Brando’s behavior had been “unprofessional and absolutely ridiculous,” and Richard Harris said working with Brando had made “the whole picture a large dreadful nightmare.”

According to Milestone and other members of the cast, Brando rarely knew his lines and would fumble his way through as many as 30 takes of a single scene. He constantly used “idiot cards”—pieces of paper with his lines written on them—which he concealed on his person or somewhere on the set.

Says Director Milestone, “It wasn’t a movie production; it was a debating society. Brando would discuss for four hours, then we’d shoot for an hour to get in a two-minute scene because he’d be mumbling or blowing his lines. By now I wasn’t even directing Brando— just the other members of the cast. He was directing himself and ignoring everyone else.

“Did you ever hear of an actor who put plugs in his ears so he couldn’t listen to the director or the other actors? That’s what Brando did. … I’ve been in this business for 40 years, and I’ve never seen anything like it. … Whenever I’d try to direct him in a scene, he’d say, ‘Are you telling me, or are you asking my advice?’ [“The Mutiny of Marlon Brando,” June 16, 1962].

While Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer hoped to recoup the cost overruns of Mutiny on the Bounty, Twentieth Century Fox was starting to see similar budget problems on its production of Cleopatra.

Robert Wise, an Academy Award-winning director, predicted Hollywood would have to change to survive. Hollywood, he said, had built up its stars in order to compete with television. In the process, it had created monsters. “Brando’s behavior has made us realize how far out of hand the situation has gotten. More and more of us are saying. ‘The hell with the star. I’ll make little black-and-white pictures with good scripts and unknown actors.’ We must do that to survive. A few more mutinies by stars and we’ll all be out of business.”

Yet the Post editors seemed to expect actors to be demanding, difficult, and hard to work with. Movie stars had to be bigger than life in everything they did. The stars of Hollywood’s golden era, like Gable and Bogart, were “exciting personalities … every gesture and mannerism set them apart from ordinary men, creating about them the aura of a star.

“Each of these old-time stars was a vibrant personality with his own distinctive style. He snarled, fumed, raged, stormed, fought, loved, bled and died with a gusto that today’s pallid actors cannot match.” The editors compared the “glittering greats” of the past with the young stars of that year and concluded, “much of the excitement has gone out of the movies.”

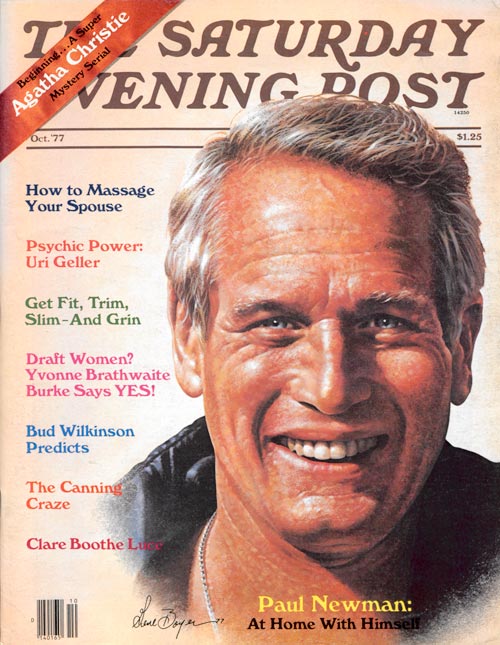

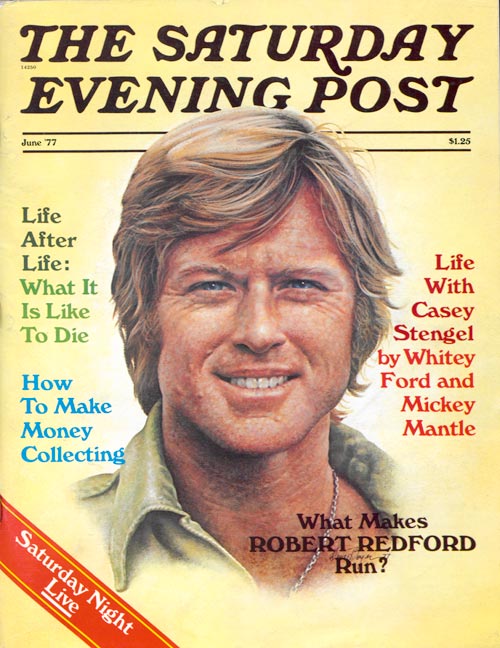

Classic Covers: Leading Men of the ’60s and ’70s

Sure, 1960’s and 70’s covers depicted the Vietnam War and politics. But happily, on occasion, a celebrity showed up. Last week, it was leading ladies. This week, celebrity covers showing some of the hottest male actors of the 1960s and 70s. We’ll call them our “leading men.”

Paul Newman by Gene Boyer, October 1977

October 1977

Illustration by Gene Boyer

Was there ever a cooler celebrity? His interests were as varied as auto-racing and large-scale philanthropy. And oh, yes, he was a darn fine actor. “Newman’s attraction as an actor has by now taken on some of the characteristics of a mythologically immortalized shrine where everyone wants to stand for a moment just to feel the magic,” wrote Erin James in the cover story. We in Indy know the mythological magic of a Newman spotting at the race track, sunglasses not quite eclipsing his handsome visage. This beautiful cover in 1977 was by artist Gene Boyer, who also did a Post cover of another famous actor and Newman pal earlier in the year (below).

Robert Redford by Gene Boyer, June 1977

June 1977

Illustration by Gene Boyer

The same artist captured not only the tousled blonde hair (sigh) and blue eyes in this 1977 cover, but the charm and intelligence as well. The baseball player in The Natural, the bearded mountain man in Jeremiah Johnson, the ambitious reporter in All the President’s Men—all worthy of another look. But combining him with Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973) was casting serendipity to be savored over and over again. Redford, of course, also gained renown as a director.

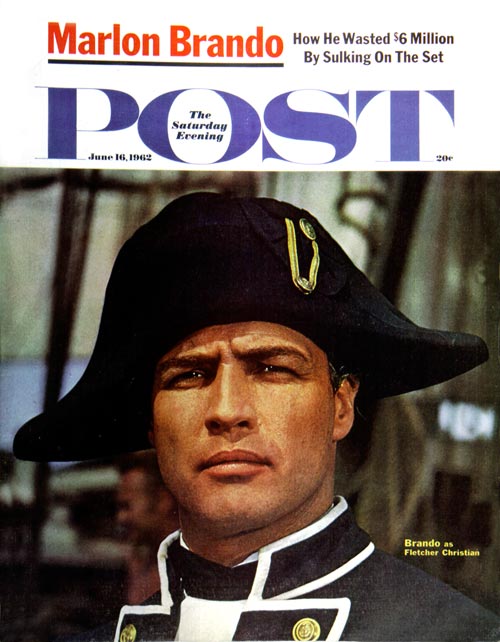

Marlon Brando by Eric Carpenter, photographer, June 16, 1962

June 16, 1962

Photo: Eric Carpenter

Billy Wilder, the noted writer-director, was having dinner with President Kennedy. “Wilder,” our article states, “prides himself on his knowledge of world affairs” and was prepared to intelligently discuss Laos or Berlin. “Instead the President devoted himself to the burning question: ‘When in the world are they going to finish Mutiny on the Bounty?'” The Brando cover had an accompanying story of how he was acting like a Hollywood brat. Gee, we’re glad that never happens anymore – well, except for Lohan. And Gibson. And…well, we digress. The director was quoted as saying the picture “should have been called The Mutiny of Marlon Brando.” Okay, in Brando’s defense, the film’s producer said “…with a modern actor like him, he’s got to feel the part and you must allow him to make his contributions to the script and the directing. Otherwise he can’t work.” We’re not advising you try to tell your boss that you’re just not “feeling” it, but that’s up to you.

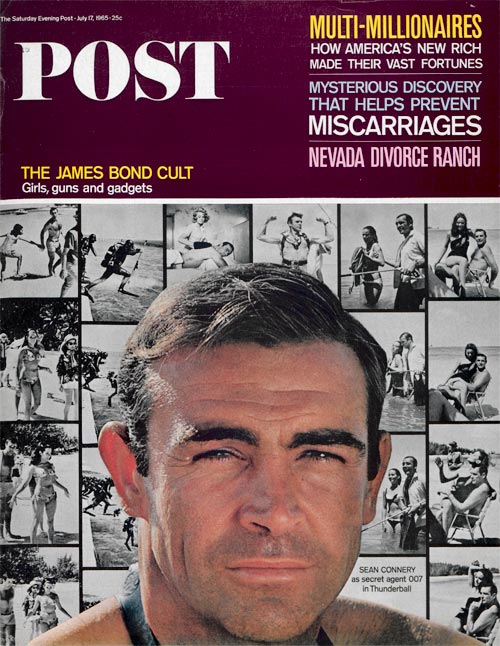

Sean Connery by Pierluigi & Loomis Dean, photographers, July 17, 1965

July 17, 1965

Photo: Pierluigi & Loomis Dean

The Bond phenomena did not escape The Saturday Evening Post. In July 1965, Sean Connery stands out against a background of Bond stills depicting “Girls, Guns and Gadgets.” There were photographers capturing Connery, all right: French, German, Swedes, English, Australian, and Canadian. “It was the biggest story I’ve ever been on,” wrote William K. Zinsser, “and it wasn’t any mere Dominican uprising or Cuba blockade. It was even bigger than that—the new James Bond movie was being filmed in the Bahamas!” The movie was Thunderball.

Richard Burton by Paul Ronald, photographer, December 3, 1966

December 3, 1966

Photo: Paul Ronald

“Richard Burton as the triumphant lover” read the caption. The lover in question was the lead in director Franco Zeffirelli’s The Taming of the Shrew. The Post cover was actually of Burton’s stunning wife Elizabeth Taylor as the shrew to be tamed (as we saw last week), and the cover cleverly folded out to show the male lead, full of all the bravado and magnetism of Shakespeare’s Petruchio…or of Richard Burton, come to that.

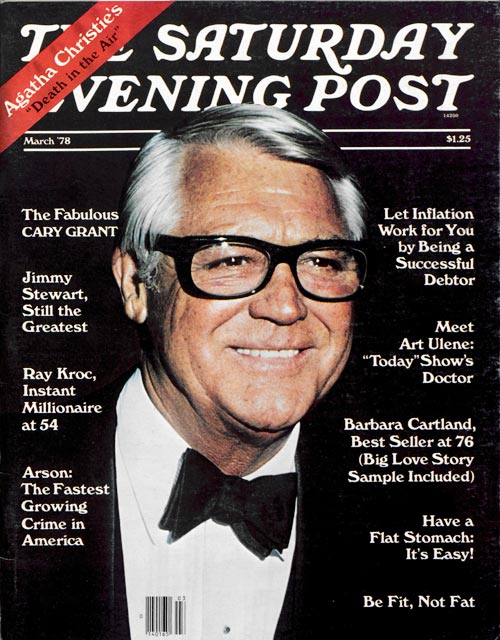

Cary Grant by Peter C. Borsari, photographer, March 1978

March 1978

Photo: Peter C. Borsari

“He’s the only actor,” wrote a Hollywood columnist, “whom other actors will turn around to see when he enters a room.” Even at age seventy-four, at the time of this 1978 cover, he was dashing and charismatic. The Post article attributed his youthfulness to “a regimen of exercise, moderation in food and drink and a penchant for enthusiasm (‘Marvelous!’ is his favorite response)”. The fact that he had a pretty thirty-two-year-old “companion” probably assisted as well. To quote actress Suzy Parker: “Who else goes to drive-in movies in a Rolls and totes champagne for refreshment?” How he managed to be charming, distinguished and funny was a conundrum we never solved, but always enjoyed. “The drama in a Cary Grant movie,” our article states, quoting critic Richard Schickel, “always lies in seeing if the star can be made to lose his wry, elegant and habitual aplomb. The joke likes in the fact that no matter what assaults and indignities the writer and director visit upon his apparently ageless person, he never does.”