“The Pace of Change” by Martin Luther King Jr.

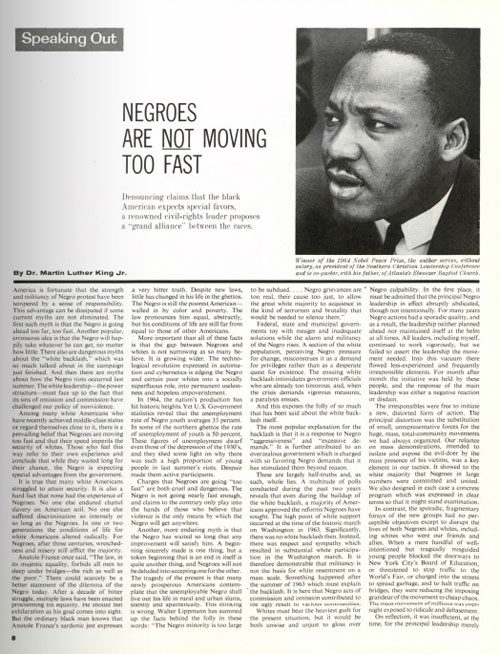

The March on Washington in 1963 seemed to herald a new era in civil rights. But in the following year, the persistence of “grinding poverty” drove some Black Americans to violence. Was progress toward equality and integration taking place too quickly, as some believed? In 1964, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., responded to that question in the essay excerpted below.

Despite new laws, little has changed in his life in the ghettos. The Negro is still the poorest American walled in by color and poverty. The law pronounces him equal, abstractly, but his conditions of life are still far from equal to those of other Americans. The gap between Negroes and whites is not narrowing as so many believe. It is growing wider.

Charges that Negroes are going “too fast” are both cruel and dangerous. The Negro is not going nearly fast enough, and claims to the contrary only play into the hands of those who believe that violence is the only means by which the Negro will get anywhere.

Another, more enduring myth is that the Negro has waited so long that any improvement will satisfy him. A beginning sincerely made is one thing, but a token beginning that is an end in itself is quite another thing, and Negroes will not be deluded into accepting one for the other. The tragedy of the present is that many newly prosperous Americans contemplate that the unemployable Negro shall live out his life in rural and urban slums, silently and apathetically. This thinking is wrong.

Federal, state, and municipal governments toy with meager and inadequate solutions while the alarm and militancy of the Negro rises. A section of the white population, perceiving Negro pressure for change, misconstrues it as a demand for privileges rather than as a desperate quest for existence. In 1963, at the time of the Washington march, the whole nation talked of Negro freedom, and the Negro began to believe in its reality. Then shattered dreams and the persistence of grinding poverty drove a small but desperate group of Negroes into the swamp of senseless violence. Riots solved nothing, but they stunned the nation. One of the questions they evoked was doubt about the Negro’s attachment to the doctrine of nonviolence.

Is the dilemma impossible of resolution? The best course for the Negro happens to be the best course for whites as well and for the nation as a whole. There must be a grand alliance of Negro and white. This alliance must consist of the vast majorities of each group. It must have the objective of eradicating social evils which oppress both white and Negro. It is not only more moral for both races to work together but more logical.

The majority of Negroes want an alliance with white Americans to tackle the social injustices that afflict both of them. If a few Negro extremists and white extremists manage to divide their people, the tragic result will be the ascendancy of extreme reaction which exploits all people.

Our nation has absorbed many minorities from all nations of the world. Many reforms were necessary — labor laws and social-welfare measures — to achieve this result. We accomplished these changes in the past because there was a will to do it, and because the nation became greater and stronger in the process. Our country has the need and capacity for further growth, and today there are enough Americans, Negro and white, with faith in the future, with compassion and will to repeat the bright experience of our past.

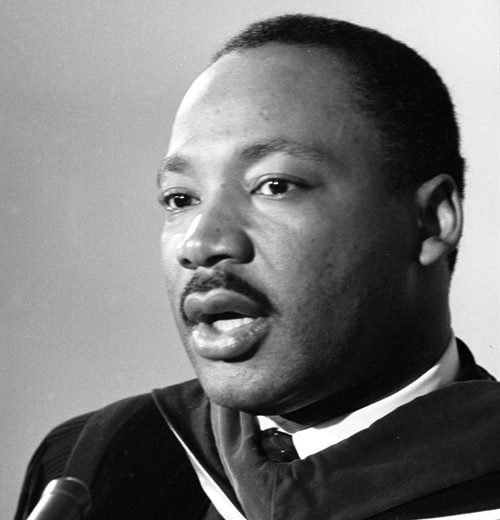

—“Negroes Are Not Moving Too Fast” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., November 7, 1964

This article appears in the March/April 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Russia’s Fake News Is Nothing New

When the Post reported on Russia’s intelligence services back in 1967, the KGB’s “Department D” did not get a lot of attention. It was the height of the Cold War (the Berlin Wall had gone up only a few years earlier) and the Soviet Secret Services posed deadly threats to the West. But today “Department D” has a new relevance.

The letter “D” stood for dezinformatsiya, a word coined by Soviet premier Josef Stalin to describe a policy of generating “fake news.” The department’s mission, according to the CIA, was to “defame and discredit” the United States by planting false or misleading articles about America in the media. Each year the department turned out over 350 derogatory news items, designed to “isolate and destroy” the United States.

Dr. Jim Ludes, who recently completed a study on Russian disinformation for the Pell Center, says that back in 1967, the Russians were exploiting racial unrest in America. They planted stories in American papers claiming Martin Luther King was a collaborator and an “Uncle Tom” because they thought his push for unity would strengthen America. After he was assassinated, they used the press to stoke resentment in the black community over his death.

Fifty years later, the old KGB is gone, replaced by the FSB, which does much of the same work and answers solely to President Vladimir Putin, an ex-KGB officer. But as American intelligence organizations have reported, some form of “Department D” is still very much alive.

According to Dr. Yuval Weber of the Daniel Morgan Graduate School of National Security in Washington, D.C., Department D is run by people like Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Putin confidante who ran a “Department of Provocations” — essentially a troll farm used to spread divisive and inflammatory stories before the 2016 presidential election. Weber says, “They engage in those sorts of activities without being official members of government, and if they’re successful can seek quasi-legitimate advertising contracts to cover disinfo operations. If they’re unsuccessful, they move on. It’s like a start-up culture in a sense.”

Russian disinformation, according to New York Times reporter Neil MacFarquhar, has one fundamental goal: “undermine the official version of events — even the very idea that there is a true version of events — and foster a kind of policy paralysis.”

Russia has aimed a torrent of misinformation at the U.S. that has deepened political divisions within our country—and many others — through the creation of fake accounts and the deployment of bots. Russian disinformation has also been at the center of controversy as President Trump and some of his political allies downplay the extent of Russian mischief and interference in our political life.

The openness that characterizes U.S. society has helped the Russians. David Darrow, associate professor of Russian history at the University of Dayton, says, “Our open institutions — our free press and free market … make us stronger, but they pose risks, and the Russians have been quick to exploit them.”

Featured image: Illustration from the “The Espionage Establishment” by David Wise and Thomas B. Ross from the October 21, 1967, issue of the Post.

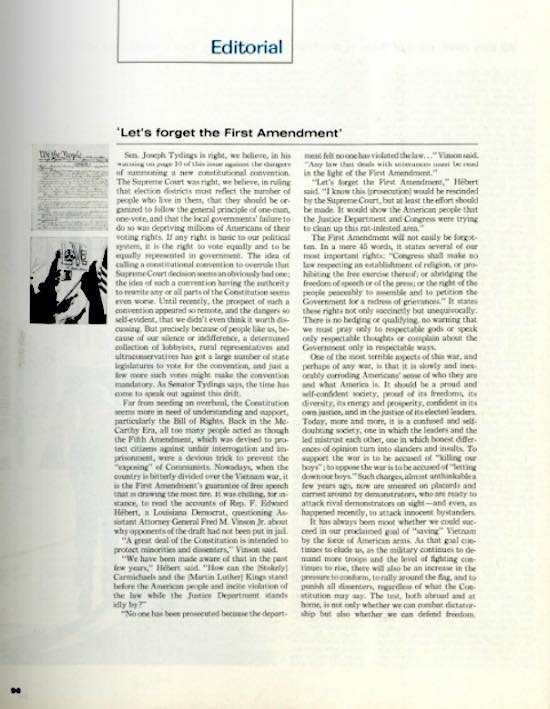

Let’s Forget the First Amendment

Not since the Vietnam War have Americans seen such an angry divide, manifested in outspoken resistance to government policies, protests, and the reaction against protests.

The current wave of public protesting began in 2013, when the Black Lives Matter movement began its street demonstrations. Protesting rose sharply after the last election when opponents of the new administration staged massive demonstrations across the country.

Now some state lawmakers are launching counter-protests through new bills. They hope to discourage demonstrations by increasing the criminality and liability of protesting.

- Legislators in Minnesota and Iowa have proposed laws that will raise the fines for freeway protesters.

- A Washington state legislator wants to reclassify civil disobedience that results in “economic disruption” as “economic terrorism” — and a felony.

- Virginia and Michigan lawmakers also want to raise their penalties on protesting, including union-organized picketing. And Michigan and Minnesota legislators want to make it easier for businesses to sue individual protestors.

- North Dakota Republicans introduced a bill that would remove the penalties for running over and killing a protestor blocking a highway if the driver’s actions were “accidental.”

Activists claim the new state laws threaten the free speech protected by the First Amendment. The laws would overturn the tradition of allowing public protests so long as the demonstrators didn’t incite violence, disrupt public meetings of police business, resist arrest, or refuse to disperse when so ordered by police.

Fifty years ago, there was similar talk of restraining protests. Thirty-two state legislatures supported the idea of a Constitutional convention that would rewrite the laws on representation and voting rights.

A Post editorial from June 17, 1967, noted that the attack on Constitutional rights had now spread to the First Amendment. Representative F. Edward Hebert had claimed that the guarantee of free speech allowed black leaders (including Martin Luther King, Jr.) to “incite violation of the law.”

His solution? “Let’s forget the First Amendment.”

He knew the Supreme Court would overrule any measure violating the First Amendment, but he thought Congress and the Justice Department should at least try to clean up this “rat-infested area” of civil protests.

There are more than a few similarities between then and now. If the present state of social conflict develops as it did in 1967, there are more protests to come.

Read the editorial, “Let’s Forget the First Amendment,” from the June 17, 1967, issue of the Post.

Featured image: Mounted policemen watch a Vietnam War protest march in San Francisco, April 15, 1967 (Photo by George Garrigues, author GeorgeLouis, Wikimedia Commons via GNU Free Documentation License)

Getting Arrested at the Democratic National Convention

Hillary’s upcoming shindig is likely to seem sedate in comparison to the zaniness of last week’s spectacle in Cleveland. But, if anything, this is a turnaround from tradition. Historically, the Democrats have been the raucous ones.

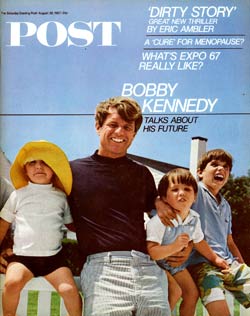

Just look at the 1968 Chicago convention. For context, recall that President Lyndon Johnson, amidst abysmally low ratings due to the unpopularity of the Vietnam War, had announced in spring that he would not run for a second term. That decision opened up the Democratic field to JFK’s brother Robert Kennedy and antiwar candidate Eugene McCarthy, as well as the more centrist Hubert Humphrey, the incumbent vice president.

In the months before the convention, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. There was the palpable sense that America was coming apart at the seams. On the convention floor, the bitterness boiled over into shouting and shoving matches, but ultimately Humphrey and the status quo prevailed.

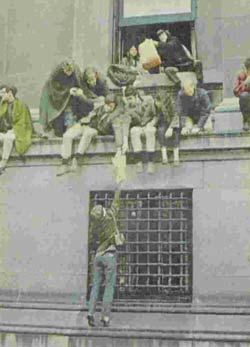

If this angered the antiwar delegates to the convention, it drove the 10,000 protesters outside into a pure and dangerous frenzy. Throughout the week, protesters were in open conflict with Chicago Mayor Daley’s security detail of 11,900 Chicago police — reinforced by more than 10,000 Army troops, National Guardsmen, and Secret Service agents.

Murray Kempton, a columnist for the New York Post and editor of The New Republic, was in Chicago to serve as a delegate for the liberal Senator Eugene McCarthy and also to write about the proceedings for the Post. After watching his candidate lose, he stepped outside to bear witness to the rioting in the streets, where he quickly found himself arrested along with hundreds of others.

The Decline and Fall of the Democratic Party

By Murray Kempton

Excerpted from an article originally published on November 2, 1968

We had arrived at 18th and Michigan, where the [national] guard and the police waited to say we could not go farther. The delegates had all found us and efficiently lined up behind Rev. Richard Neuhaus and me, since, for reasons obscure but connected with the failure of its beginning, ours was known as the Neuhaus-Kempton group. Such then was my last caucus; and, when Dick Gregory [the former comedian turned antiwar activist] went forward to get himself arrested and the Rev. Mr. Neuhaus to treat with the police, not knowing the procedure for getting arrested in Chicago as well as Gregory, I found myself stranded as its leader. Gregory’s blacks were juking in front of us; and [pacifist David] Dellinger’s strayed grays were no doubt preparing some manifestation behind us; and there fell upon me the sickening dread that at least two of our repertory companies were about to start their productions while ours, the amateur one, could not even think of its script.

Then Neuhaus returned at last, welcomed as no servant of the Lord often is, and said we should advance to confront the guard. There was nothing to do but get arrested, which took an unconscionably long time, during which we sat down symbolically, and then got up, because Gregory’s pards felt that it was about time to go into their performance and that we ought to stand and afford them free passage. A National Guard lieutenant colonel finally read his office over me, and I was moved, correctly but not cordially, into the wagon. Its bag was a mixed one of delegates and stray young people; riding over, the young called out “Free Vietnam” to the invisible streets outside. “Free assembly,” I ridiculously croaked.

In my usual job, you come to think of policemen as very much the same; when you are under arrest, they turn out to have quite extraordinary range. I should say that I met three nice cops for every nasty one; what surprised me was how far our permissive society has gone even with cops: A pleasant one feels free to be unusually pleasant and a mean one feels free to be unusually mean, neither of which tones is exactly what the book must command for treatment of that offender against society who is also its ward.

“Give me everything you’ve got with a sharp point,” the one who searched said. “One of you peace lovers put out an officer’s eye with a pin once. Do you know that?” He found a token that somebody had slipped me a long day ago and that I had put in my pocket without even looking at. It turned out to have the likeness of Martin Luther King on it; and he threw it to the floor. “Martin Luther Coon,” he said, grinding it with his shoe; “you all come from the same bag.” To my shame I did not make reply and only shuffled along, which is why it is so necessary never to be surprised. Yet, after this caricature, the trip to the Dark Tower, while tedious, had illogical moments of good manners. “What is a distinguished-looking man like you doing being arrested?” one of the booking detectives asked. I had no answer; the question, kindly meant, could only make me understand that I was getting old.

But, after a while, these desultory excursions into the study of policemen were driven away by the revelation of the other persons who had been arrested that night. The journey crept along in the company of The Professor of Physics at Stevens Institute and The Personnel Director of the Perth Amboy Hospital, The Telephone Company Lawyer, and then it would end in the waiting outside Riot Court, the Dark Tower itself, with the finding there of Harris Wofford, the President of A New York State University, of The Man from The New York Times, and The Rockefeller Man from Kentucky.

What could have brought them here in police custody? I knew why I was here; I had taken a contract. But what brought them, these safe men who had never before been arrested and probably never would be arrested again? It must be the indefinite suspension of their assurance of the virtue and redemption of America. The means of grace and the hope of glory had been taken away, because, after all, America had been their real God. And this night, otherwise inconsequential in our dreadful recent history, was The Night They Knew It.

But I could almost feel each of them, in his private heart, tending all afternoon toward this least dignified of places as the only one where they could be sure of being alone with their dignity. For them to have been in public that night would have been to rail or make bad jokes there; they had gone to the patrol wagon for privacy.

We stood about and talked among ourselves as men unused to arrest probably do; Dellinger’s stray young grays, who had been there before and would be again, slept on the floor. I felt quite tender about them, because I had noticed that although they sometimes carry signs bearing the device of some four-letter word or other when they are on-camera, they do not write dirty words on the walls of detention rooms. Do they, among other reasons, go to jail for privacy too?

There is very little to the rest. We went on talking; The Man from the Times came out from the Dark Tower and said this was a rough judge; he had been told to stop slouching. (I cherish The Man from the Times, but, in fairness to the judiciary, he does slouch.) My name was called; I entered the Dark Tower. And there, as usual with me, the first sight, instead of the Beast, was the warm bright greeting of William Fitts Ryan, my congressman; the convention was over and he had generously come down to be my lawyer. Bill Ryan unsheathed his congressional identification card and gave rein to his imagination for hyperbolic explanations of the distinction of his client; the judge struggled to the summit of whatever foothills of grace are afforded by night courts, and I was set loose.

For a complete inside look on the 1968 Democratic National Convention, read the full text to Murray Kempton’s “The Decline and Fall of the Democratic Party.”

The Post Reports: The Long March on Washington

Fifty years ago, the hot topic in the Post was integration. We begin a series on the Post‘s civil rights reporting with original material from Martin Luther King Jr., James Meredith, Malcolm X, and other influential civil rights leaders and journalists.

The Rise of the Black Activists

By 1963, black Americans were taking control of the fight for civil rights. Read More »

The Deep South Says Never

In 1954, the White Citizens’ Councils began a campaign of intimidation to shut down the movement toward integration. Read More »

Black Students, White Schools

The Supreme Court ordered an end to segregated schooling, but the transition would not come easily. Read More »

Black Neighbors, White Neighborhoods

Throughout the ‘50s, white homeowners were panicking at the thought of blacks moving into their neighborhoods. Read More »

‘It’s Our Country, Too’

In 1940, civil rights activist and NAACP leader Walter White wrote a column for the Post examining how black Americans’ desire to serve their country was held back by government discrimination. Read More »

A Voice From a Truly Violent Year

Journalist Lance Morrow once wrote that the day John Kennedy was killed was the day the U.S. stopped believing it could choose its destiny. Faced with a rising tide of violence, he argued, Americans came to accept the future was beyond their control.

That sense of powerlessness would only be strengthened by the killing sprees that have become more frequent over the years. Since Charles Whitman shot 14 students at the University of Texas at Austin 46 years ago, 22 other Americans have opened fire on strangers in restaurants, schools, and, most recently, a movie theater. From 1990 to 2000, there were four of these shooting sprees. There have been six in the past two years.

When viewed alongside the current wave of political hostilities and mistrust in the country, some Americans have been tempted into seeing an imminent collapse of society. Sooner or later, the thinking goes, this streak of violence in American society will push the country to some disastrous end.

For perspective’s sake, we thought we’d offer some reflection on this subject from someone who lived in a truly violent and troubled year. In a Post article of 1968, Daniel Patrick Moynihan asked, “Has This Country Gone Mad?”

“Violence has rarely been altogether absent from American life… But I think the violence of this age is different: It is greater, more real, more personal, suffused throughout the society, associated with not one but a dozen issues and causes.

“The rise of black violence has been an… ominous and irrational turn… White terrorism against Negroes is an old and hideous aspect of American life, but… now it seems to be becoming a pastime for suburban housewives, taking target practice before television cameras, filling black silhouettes with white holes.

“Protest against war has been an old and honorable tradition in America, but with this war [in Vietnam] the peace movement itself has turned violent, threatening elected officials…

“One group after another appears to be withdrawing its consent from the agreements that have made us one of the most stable democracies in the history of the world.

“The espousal of violence, and violence itself, mount on every hand: private crime, organized crime; civil disorder at home to the point of insurrection, violence abroad on a scale unimagined.”

Keep in mind what was taking place as Moynihan was writing. In 1968, black militant activists were promoting violent resistance to white society. Black Panthers and policemen were trading shots in Oakland, Calif. The war in Vietnam was expanding: the Tet Offensive had brought enemy troops to the gates of the American Embassy in Saigon, and the U.S. began moving troops into Laos. Anti-war protestors became more militant; students took over Columbia University and rioted outside the Democratic convention. The murder of Martin Luther King Jr. and the subsequent riots were barely a month in the past. Just a few months later, Robert Kennedy would be assassinated while campaigning for the presidency.

In 2012, as the media reports (and sometimes promotes) messages of bitter social division, the separation between conservatives and liberals seem wider than ever before. But for all the bluster and threats, it still isn’t as great as in 1968. Back then, reactionaries and radicals were trying to overturn society, while a great number of Americans seemed willing to watch the collapse.

“A good many Americans do not hesitate to conclude from all this that American society is doomed, and they make no effort to conceal their great pleasure at this prospect. The ‘lust for apocalypse’… is something formidable to behold, especially in… the Ivy League radicals… [Meanwhile] Gov. George Wallace of Alabama… will have millions of Americans voting for him for President next fall… In East Harlem, a school official advises black children to get themselves guns and to practice using them. On silhouettes of suburban housewives, perhaps.

“Increasingly the nation exhibits the qualities of an individual going through a nervous breakdown. Is there anything to be done?”

Not a great deal, Moynihan answered, but a good beginning would be to abandon the myths that we could either control events or we were helpless. It would help, he said, if we “try to understand our collective strength as a people, and to try to see what is happening to that strength.

“The great power of the American nation…lies in our capacity to govern ourselves.

“Of the 123 members of the United Nations, there are fewer than a dozen that existed in 1914 and have not had their form of government changed by force since that time. We are one of those very fortunate few. More than luck is involved.”

What separated us from them was “the ability to live with one another.” America had been so brilliantly successful at this that we no longer appreciated it. It was time to remember what an accomplishment creative harmony was.

“An Englishman, an expert on guerrilla warfare, put it concisely to a Washington friend about a year ago. The visitor was asked why American efforts to impart the rudiments of orderly government seemed to have so little success in underdeveloped countries. ‘Elemental,’ came the reply, ‘You teach them all your techniques, give them all the machinery and manuals of operation… The more you do it, the more they become convinced and bitterly resentful… as they see it… you are deliberately withholding from them the one all-important secret that you have and they do not, and that is the knowledge of how to trust one another.”

This ability to trust, he continued, would not survive all the reckless talk about dissolution and despair. We shouldn’t come to accept civil hostilities and divisions as the natural state of America. “There must be a stop to this trend toward violence, and in particular, an immediate and passionate objection to any voice that gives aid and comfort to the present drift of events. That is almost a violent statement itself, but one surely warranted in the present state of the American republic.”

The Dangerous Doctor King

American history is filled with heroes, but only three are honored with national holidays — Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and Martin Luther King Jr. Of these, only the latter two were born in America, and Washington’s birthday also serves as President’s Day to honor all other presidents. Martin Luther King Jr. has his own holiday (although, the state of Virginia combines his holiday weekend with Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson Day).

A dedicated national holiday is a unique honor for an American, particularly when he was regarded with dread and suspicion in his own time.

Civil rights have always been a troublesome issue for a country that is publicly dedicated to equality. But for many years, the fate of minorities in the United States was only a peripheral problem to American society; white Americans could live their lives without ever confronting the problems of racism and segregation.

That began to change in the mid-20th century. The U.S. Federal Government secured the support of black Americans for the war effort by offering them new chances for advancement, both in the military and in military contracting. In 1954, the Supreme Court decided there could be no legal justification for racial inequality. States could no longer justify segregated schools. In 1955 Rosa Parks inspired 50,000 black Americans to protest segregation on buses in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1957 President Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock to enable black students to enroll in the local high school. Black activists staged sit-ins in the 1960s, and Freedom Riders took Ms. Parks’ protest further, testing the government’s willingness to support integration on interstate transportation.

In a relatively short time, the issue of race had moved to center stage. Some white Americans who had always enjoyed the full benefits of their rights had difficulty understanding the black Americans’ impatience and mistrust of the government. And they wondered about the charismatic leader who had emerged from this movement and talked boldly of immediate action. Martin Luther King Jr. made civil rights an issue that could not be ignored or dismissed as racial politics. It was an American issue.

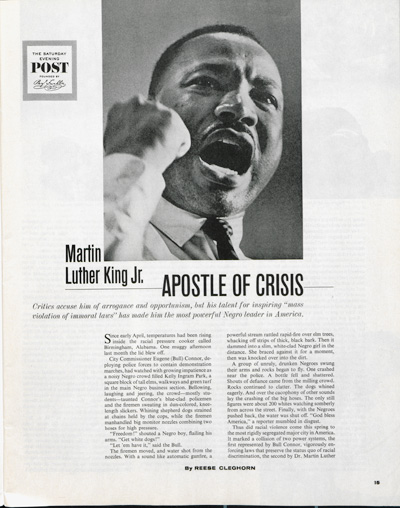

The Post published an article about Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963. Its author, Reese Cleghorn, recognized the need for integration, but he was skeptical about King.

He reported the Birmingham riots as if he had no stake in the conflict between black Americans fighting for their overdue civil rights and white racists who wanted to refuse them. Cleghorn seems to have gathered up every criticism he could find about King — though he was too busy to include the name of his sources.

For instance, he links King with violent black protesters:

“Thus did racial violence come this spring to the most rigidly segregated major city in America. It marked a collision of two power systems, the first represented by Bull Connor, vigorously enforcing laws that preserve the status quo of racial discrimination, the second by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. making a carefully planned assault on those laws and that discrimination.”

He presents King as a dangerous provocateur:

“[King] lighted a fire under the pressure cooker, well knowing that the ‘peaceful demonstrations’ he organized would bring, at the very least, tough repressive measures by the police. And although he hoped his followers would not respond with violence — he has always stressed a nonviolent philosophy — that was a risk he was prepared to take. Two months earlier his No.1 staff assistant, the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, had explained, ‘We’ve got to have a crisis to bargain with. To take moderate approach, hoping to get white help doesn’t work. They nail you to the cross, and it saps the enthusiasm of the followers. You’ve got to have a crisis.'”

King was imperious:

“For these and other reasons, some integrationist leaders felt that King had blundered in bringing crisis to Birmingham. It was not the right place, they maintained; this was not the right time; and mass marches to fill the jails—a tactic that bears King’s personal brand—was not the right tactic. Further, King had gone into Birmingham not only against the advice of these leaders but without even informing them. ‘That’s just arrogant,’ one said in exasperation.”

King was self-serving:

“Other detractors within the desegregation movement have bitterly accused King of tackling Birmingham primarily to raise money and to keep his name and his organizations, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), out in front on the teeming civil-rights scene.”

He was playing with fire:

“King’s magic touch with the masses of Negroes remains. They do not understand the intricacies of his tactics. What they see is a powerful crusader for equality who does something instead of just talking, who sticks lighted matches to the status quo and who is impatient with talk of waiting. Given the increasing unrest among Negroes, King’s flare seems likely to spread a trail of little Birmingham’s through the nation during the next few months.”

He was out of his depth:

“King bears heavy organizational responsibilities, and it is in this realm that he is most criticized.”

He was immoderate:

“Seven leading Alabama churchmen, some of whom had staked their prestige and positions upon a moderate solution in Birmingham, had openly criticized [King’s] actions there. He answered them with a publicly released 9,000-word letter … [which] split him from the white moderates of the South and suggested that Negroes would plot their own course in the future.”

Martin Luther King Jr. might have looked threatening to white Americans in the early ’60s, even those that considered themselves informed and fair-minded. He appeared far more attractive in a short while, though, as angrier voices arose in the black community. When the Black Muslim church started gathering supporters and Black Panthers became active, Dr. King suddenly seemed extremely moderate, reasonable, and comfortable.

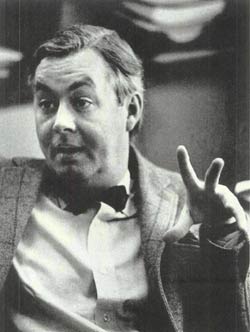

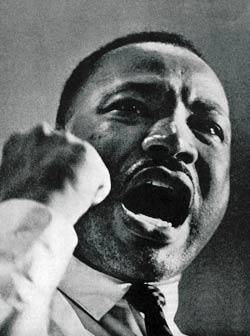

Overall, Cleghorn tries to be informed, but he was writing from a time when middle America still felt it had the luxury of disapproving and dismissing the voices of black America. Cleghorn does little to allay fears of future riots and racial violence. Even the chosen photograph seems to heighten the effect; you’d have to look long and hard to find a more menacing picture of Dr. King.

Click here to read Cleghorn’s original article from 1963 [PDF].

President Obama to Speak at NAACP

A Proud Moment in a Long Struggle

President Obama will be in New York on July 16 speaking to a crowd of 10,000 people. While he has addressed much larger groups, rarely has he spoken on such a significant occasion: America’s first black president will be giving the keynote speech at the 100th birthday celebration of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The NAACP was formed in 1909 to address a rising opposition to civil rights. Racism in America was discarding its subtlety, coming out in the open, and making a new bid for power. Southern legislators had enacted new laws that made it difficult, if not impossible, for black Americans to vote. Racial tensions ignited race riots, and more were coming.

Dr. W.E.B. DuBois edited the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, and helped frame the association’s goal:

“To promote equality of rights and to eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for the impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the court, education for the children, employment according to their ability and complete equality before law.”

The early years were daunting and Washington extended little sympathy for the cause. The NAACP addressed the need to end official segregation, promote black men to officers in the military, and oppose the rising enrollment in the Ku Klux Klan. The effort met consistent opposition from southern legislators who blocked federal legislation against lynching.

Halfway through its first century, the NAACP was confronting racism as virulent as ever. Black Americans were achieving some of their goals, but they were also being accused of seeking their rights too aggressively.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Nov. 7, 1964

In the November 7, 1964, Post, Dr. Martin Luther King addressed this issue directly in his article, “Negroes Are Not Moving Too Fast.”

“Among many white Americans who have recently achieved middle-class status or regard themselves close to it, there is a prevailing belief that Negroes are moving too fast and that their speed imperils the security of whites. Those who feel this way refer to their own experience and conclude that while they waited long for their chance, the Negro is expecting special advantages from the government. It is true that many white Americans struggled to attain security. It is also a hard fact that none had the experience of Negroes. No one else endured chattel slavery on American soil. No one else suffered discrimination so intensely or so long as the Negroes. In one or two generations the conditions of life for white Americans altered radically. For Negroes, after three centuries, wretchedness and misery still afflict the majority.

“Anatole France once said, ‘The law, in its majestic equality, forbids all men to sleep under bridges—the rich as well as the poor.’ There could scarcely be a better statement of the dilemma of the Negro today. After a decade of bitter struggle, multiple laws have been enacted proclaiming his equality. He should feel exhilaration as his goal comes into sight. But the ordinary black man knows that Anatole France’s sardonic jest expresses a very bitter truth. Despite new laws, little has changed in his life in the ghettos. …

“Charges that Negroes are going ‘too fast’ are both cruel and dangerous. The Negro is not going nearly fast enough, and claims to the contrary only play into the hands of those who believe that violence is the only means by which the Negro will get anywhere. …

“A section of the white population, perceiving Negro pressure for change, misconstrues it as a demand for privileges rather than as a desperate quest for existence. The ensuing white backlash intimidates government officials who are already too timorous, and, when the crisis demands vigorous measures, a paralysis ensues. …

“Our nation has absorbed many minorities from all nations of the world. In the beginning of this century, in a single decade, almost nine million immigrants were drawn into our society. Many reforms were necessary—labor laws and social-welfare measures— to achieve this result. We accomplished these changes in the past because there was a will to do it, and because the nation became greater and stronger in the process. Our country has the need and capacity for further growth, and today there are enough Americans, Negro and white, with faith in the future, with compassion, and will to repeat the bright experience of our past.”

The NAACP has no reason to close operations this year. There is, alas, still more work ahead. However, we hope they, and the country, savor the moment when President Obama shares the podium with America’s first black secretary of state, Colin Powell, and our first black attorney general, Eric Holder. America should be very proud of this organization and the long dedication of its generations of members.