North Country Girl: Chapter 25 — No Smoking

After those weekend parties, I walked home alone through the frigid Duluth night, warmed by a sense of belonging, of acceptance. I had found a place in the world, and even more importantly, in high school. My gang of girls ebbed and flowed around me like a school of friendly, benevolent fish. We had our own designated cafeteria table within reach of an artlessly tossed roll from the table where the cute boys sat. Among the hundreds of other kids at East High, we had an uncanny ability to find each other; we never walked alone down those not-so-mean hallways. At birthday sleepovers, all of us would be there, bearing gifts of warm beers, jars of watered-down Beefeaters decanted from our parents’ bars, and packs of Tareytons, the gang’s cigarette of choice. I desperately wanted to be a smoker, like my friends, who tried to teach me how to inhale. I was unable to get past that first puff without coughing until my eyes were bleary, teary, and crossed. Nancy Erman would pound me on the back then pluck the ciggie from my hand to finish it herself.

I spent hours of each school day with Nancy, my own St. Peter who had ushered me into this heaven. We sat next to each other in all our advanced classes. We didn’t whisper or pass notes, we just vibrated together in the comforting solidarity of friendship.

Although most of my new gang had boyfriends, Friday nights were Girls Only, a rule we held to through all three years of high school, including summers. Saturday was date night; if you didn’t already have a steady boyfriend, this was when you tested out new guys at the Norshor or Granada movie theater, or over weird hamburgers at Somebody’s House, or making out in the back seat of a car. My heart-breaking experience with Steve LaFlamme had tamped down my desire to have a real boyfriend; this was a good thing, as outside of the slowly disintegrating Brad McCarthy, no boy seemed interested in me. Most Saturday nights a few phone calls would round up one or two other luckless friends and we single girls would hang out, drink, and look for unclaimed guys. On those nights when all of my friends were paired up with steady or prospective boyfriends, I sat at home, eating popcorn and watching Saturday Night at the Movies with my sullen sister Lani, who only looked up at the TV intermittently between scrawling nipples and pubic hair on all her Barbies with a black Magic Marker.

My friends took it for granted that since I was now a popular girl that I would, like all popular girls do, eventually land a boyfriend, the invisible magnet of popularity snaring and reeling in at least one boy. Even Carol, who despite her constant dieting, seemed to put on a pound a week, was out every Saturday night with big blond Artie, who never spoke but whose size earned him a starting spot on the varsity hockey team. As a token of love, before heading into the penalty box Artie always sent Carol a besotted wave of his gloved hand while standing over the body of his latest victim, who lay sprawled and bleeding on the ice.

Drifting along in my happy cloud of girlfriends, I had almost forgotten about Mary Ann Stuart until I got a letter asking if she could spend a week of Christmas vacation with me, since she had already told her mother I had invited her. Mary Ann arrived in late December, with a deep Florida tan, even bigger breasts, a gift of silver earrings for my still-crusty pierced ears, and disturbing news: we were double dating that night with a friend of John Bean’s.

It was a Friday night. I had looked forward to bringing Mary Ann along when I met up with my gang. They were not an exclusionary bunch, and Mary Ann knew some of the girls from the Deeps. But Mary Ann was too gaga over seeing, and kissing, and being felt up by John Bean to even consider the prospect of drinking lukewarm Fitger’s beer in Wendi Carlson’s bedroom while her mother was at bowling league.

I was torn. Even as it sunk in that I was only the Holiday Inn, that Mary Ann had really come back to Duluth to see John Bean, the code of honor among girlfriends meant that I couldn’t back out of the double date. I called Wendi and said we weren’t coming. Not showing up on a Friday night didn’t mean that you were ostracized or kicked out of the gang; knowing that you had missed out on the fun was punishment enough.

Skipping that Friday night with my friends was the first step in my accidental acquisition of a boyfriend. My date was Doug Figge, a pimply, unremarkable kid whose sole distinction was the ability to grow a slight moustache, a moustache that a first glance looked drawn on with eyebrow pencil. John Bean and Doug Figge went to the mysterious Central High, reputed home of tough guys and greasers, and they worked together at the Canal Drive-In.

Our dates dutifully arrived at seven and manfully shook hands with my father. Had Mary Ann not been there, my dad would never have allowed his just-turned fifteen-year-old daughter to get into a car with two scruffy boys with shaggy hair wearing black leather jackets completely unsuitable for Duluth winters. That must have been some sizeable golf bet.

We did not go to Somebody’s House, home of gourmet burgers and real tablecloths. We did not go to the London Inn, the drive-in that was the teeming heart of Duluth teen social life, the destination for every kid with access to a car. We didn’t even go to the Canal Drive-ln, where John and Doug worked, a joint that offered second-rate hamburgers and zero ambience.

We went to Joe Sloan’s house, Joe who had played wingman to Wesley Baggot. I hadn’t been to that house for seven or eight years, back when Joe’s younger sister and I had occasionally played together. The gatehouse and the long driveway leading up to the massive Tudor Revival mansion, ominously stark against the snow, the gleaming grand piano lurking in the immense living room…it was all as familiar and as strange as a dream. Joe, who quickly shooed us inside his oddly dark and silent house, was no taller than he had been when I last saw him six months before, but he seemed older. He mumbled, “Hi Gay, something something” and again I got lost in his dark, deep eyes. I decided I did want a boyfriend, even if he was shut up at boarding school most of the year.

The five of us trooped down to the basement, which disappointingly looked like every other basement rec room used mostly by kids: sticky checkered linoleum tile floor, ping pong table with a torn net and one paddle, scratchy couches with hideous crocheted throws, and an aluminum standing lamp with a single working bulb. In keeping with dating etiquette, I had to sit next to Doug, while sending out frantic thought beams to Joe Sloan: HE’S NOT MY BOYFRIEND.

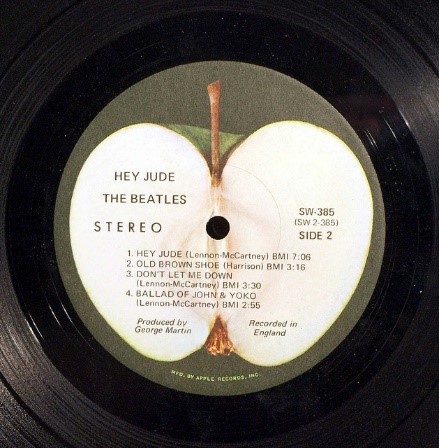

Joe did have a real stereo system, with separate turntable and speakers, instead of an RCA hi-fi disguised as a piece of classy furniture, or the tinny shoebox-sized contraption I received free (hah!) with my membership in the Columbia Record Club. Joe put “Hey Jude” on the turntable, that seven-minute drone that had been played over and over all fall in every basement and on every car radio. I wasn’t a fan of the B side “Revolution,” either, I just might want to carry a sign by Chairman Mao. But I smiled and twinkled at Joe as if I were the world’s biggest Beatles fan and ever so grateful to him for playing that particular track: Nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah…

Joe was not paying the least bit of attention to me as he was busy doing something with a small piece of paper. When he lit it on fire, I realized that here, at last, were drugs. The joint was passed around, refused by Mary Ann (“It makes me feel weird”…wasn’t that the point?) and came to me. I was thrilled that finally I was about to experience that transport of consciousness I longed for and scared to death that I would blow it, which I did. I took my first hesitant puff of a joint then erupted in a coughing fit a hundred times worse than a Tareyton one. Kind Nancy was not around to pound my back, Mary Ann just looked on, mortified. None of those boys ever offered me pot again.

Joe started to flip over “Hey Jude” when Doug handed him a Doors album, which gave Doug one point in my eyes, but did not make up for the pimples. No one talked, not even John and Mary Ann, the reunited lovers, who did eventually sneak away somewhere. The Sloan mansion had dozens of rooms they could use; it was a miracle they found their way back to the basement hours later. When Joe and Mary Ann left in search of a private love nest, Doug put his hand over mine, I scooted away, and Joe shut his gorgeous eyes.

That was my week with Mary Ann. If we weren’t in Joe Sloan’s basement, we were lounging around in my bedroom while she told me how much she loved John Bean, how it felt when he touched her, how every night a new piece of clothing was discarded and a new body part caressed.

Mary Ann sweet-talked my mother into driving us down to the Canal Drive-In, where Mary Ann and John traded looks of undying love over the sticky counter while John wrapped hamburgers in waxed paper. The garish yellow and red Canal was lit like an operating room, with chairs meant to encourage you to eat your burger and leave as fast as possible. Coming out of the crisp wintery air, the atmosphere at the Canal was a fug of uncirculated grease. Mary Ann and I sat there, scrunching our bottoms around in those plastic bucket-shaped seats, sipping cokes through paper straws until John and Doug got off their shift and it was off to the Sloan’s basement.

Mary Ann had not flagged in her crusade to pair me up with a boyfriend. She insisted that I like Doug: after all Doug had told John who had told Mary Ann how much he liked me, even though I don’t think we had exchanged ten words. On that basis, one night while Joe slipped into a pot and “Hey Jude” induced trance, Doug and I kissed and did the teen couple couch grapple.

Doug was a boy, so that was exciting, and he was a year older and had a driver’s license and smoked cigarettes and pot. He liked the Doors and he seemed to like me. I tried to like him back, as Joe Sloan still treated me as an inanimate object and there were no other contenders for boyfriend ringing me on the phone or walking me home from school.

Doug did not have all that much going for him as boyfriend material. A pong of French fries always clung to his hair. He went to a different high school so we would never walk hand in hand to class together. I hated going over to his pokey ranch house, which sat on a small, treeless plot in a neighborhood I had never been to before. His grey, sunken-faced parents, who didn’t speak to me, were always watching TV, slumped in matching Barcaloungers too large for their cramped living room. Plastic flowers stuck in empty bottles of Lancers and Blue Nun wine decorated the dining table and sideboard. There was not a single book in that house. I looked down my nose at all of it. I was a hippie, I was a revolutionary, I was a snob.

After her week of love, Mary Ann said goodbye to me through a veil of happy/sad tears: she and John had spent their last night together going all the way. Mary Ann claimed that he had a rubber, but as it was pitch black in that forgotten back bedroom in the Sloan mansion, she could not enlighten me as to how a rubber went on or came off, but who cares, she cried, it was magical, it was heavenly, she loved John Bean so much and he loved her, and she hoped that Doug and I would be just as in love. The sex sounded fun, but I could not imagine Doug Figge on the other end of a mysterious rubber-sheathed penis.

Mary Ann flew home to Florida, Joe Sloan was sent off to his bad boy boarding school, and I went back to East High and the company of my friends; a week away from them felt like an eternity. The girls were thrilled that I finally had a boyfriend, even if he did go to another school and therefore had no status, good or bad, in the East High caste system.

I wasn’t sure I had a boyfriend, or even wanted this particular one. But Doug beat out the competition, as there was none. He’d call, ask me out, and I went, Saturday after Saturday. We didn’t go to the movies or to Bridgeman’s for ice cream. We went to his sad little house, or if John Bean was working, down to the Canal Drive-In where John gave us free onion rings and cokes. When the Canal closed, John and Doug smoked pot and drank beers in the parking lot, while the gale-force wind off the lake buffeted the car. I sat smashed between them, trying not to cough as the air in the car turned blue with smoke. Doug and I would end the evening in the back seat of his parents’ Corvair, negotiating how much I really liked him.

I had no problem letting Doug stick his hand under my shirt. Mary Ann had warned me not to make the same prissy mistake I had with Steve Laflamme. Thanks to sleep-over confessions, I now knew that every girl in my gang who had a boyfriend of several months’ standing had gone at least that far. We girls prided ourselves on sharing everything, starting with the first kiss; our Friday nights were filled with drunken truth-telling and laughter, at ourselves, each other, and our clueless boyfriends. My gang of friends bonded over tales of our teenage romances and the knowledge that all our secrets were safe among us.

North Country Girl: Chapter 24 — Boyfriend and Girlfriends

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My friend Mary Ann Stuart was even more excited than I was at my landing a boy. “You like Steve, right? He’s cute. I think he’s cute, not as cute as Dave, but cute. I think he likes you a lot.” This was all we talked about as we walked from her house to the Deeps, where we spread our towels on a flat rock and rubbed baby oil on each other’s backs. Dave and Steve extracted themselves from a clutch of Cathedral High boys and came and sat with us. My life was complete. A boy liked me. We were SteveandGay, one of the acknowledged couples of the Deeps.

We started leaving the Deeps while the sun was still high, eager to get back to Mary Ann’s dimly-lit cabin, each day spending less time watching other boys make harrowing jumps into the river, and more time paired off, Mary Ann and Dave doing who knows what in her bedroom, Steve and I entwined on the couch, WEBC on the radio, playing that summer’s top 40. One afternoon, “Sunshine of Your Love” came on, and I could feel Steve shift his weight on me, pushing me deep down on the sofa and releasing another layer of dust. At the same time, his right hand cupped my bikini-enclosed breast. Without thinking, I grabbed the offending hand and pulled it off. Steve yanked his hand out of mine and stuck it back on my chest. We repeated this a few times before he sat up and asked “Why?” I couldn’t answer, “Because that’s what I think I’m supposed to do,” which was the truth. I said, “I don’t want to” and made a show of draping my shirt over what were my obviously irresistible breasts.

Steve looked down at the floor, then got up, banged on Mary Ann’s door, and shouted “Dave! I gotta go!” I had landed and lost a boyfriend in less than a week.

When Mary Ann and I got to the Deeps the next day, there was Steve. Talking to another girl. He did not so much as look my way the entire day. I wanted to pull my towel over my head or throw myself on top of that deadly refrigerator.

“What happened?” asked Mary Ann. “I thought he liked you.” She was horrified that I had lost my first boyfriend because he was trying to cop a feel. “Why didn’t you let him?” Mary Ann scolded me. “I don’t know,” I wailed, on the verge of adding to my public humiliation by bursting into tears. But what could I do now? I couldn’t go over to Steve and tell him I changed my mind, he could touch my breast if he wanted to. Mary Ann and I wracked our brains trying to figure out something to tell Dave to tell Steve that would give me a second chance. But it was too late. The next day at the Deeps, I got to watch Steve put his arm around his new girl, her mouth wide with laughter as she gazed adoringly at him. Mary Ann scooped up our stuff and hustled me back to her house, where I had a good cry until Dave showed up and I trudged home alone.

I didn’t go back to the Deeps that summer. I still hung out at Mary Ann’s house when Dave wasn’t around, which was more and more as summer tilted towards fall and the start of football practice. Mary Ann had begun to cool on Dave when he showed up sporting a Johnny Unitas buzzcut. A new boy began hanging out at Mary Ann’s. John Bean was sixteen and had a car and money from his job at the Canal Drive-in, down on Duluth’s tatty lakefront. Dave, stuck on the playing fields of Cathedral High School, was history. I spent the rest of my time with Mary Ann listening to how much she loved John Bean up until the day her father put her on a plane to Florida.

I confessed the whole sordid story of getting dumped by Steve to Cindy Moreland, who was a sympathetic ear and insisted that I had done the right thing, not letting a boy touch me there. I wasn’t so sure.

Cindy was in the midst of an audacious plan: a back to school boy-girl party. Neither Cindy nor I had ever been invited to a boy-girl party, although we had heard of raucous ninth-grade goings-on at houses where the parents were away for the weekend. There were rumors of beer drinking and couples sneaking off to dark bedrooms; at one out-of-control party at the home of one of the most popular girls, Michelle Messier, the door to the refrigerator somehow got torn off and Michelle was grounded for the rest of her life.

Unfortunately, at Cindy’s party her parents were watching TV upstairs while a dozen of us kids sat around her basement, sipped cokes, burned our mouths with Jeno’s pizza rolls, and listened to records, until someone turned down the music and started a mildly exciting game of Truth or Dare.

Cindy had decided that my glasses were too weird and off-putting and I shouldn’t wear them at her party, especially because she had invited boys from Ordean, the other junior high, boys who didn’t know of our reputation as non-starters. Without my glasses I could barely make out Cindy’s face and everyone else at the party was an indistinguishable blur. I worried that if I had to pee I wouldn’t be able to find my way upstairs to the bathroom.

As I put down my giant glass of Coke, I heard my name and rashly called out “Dare!” I was dared to go into a closet and kiss Brad McCarthy, whoever he was. One of the blurs stood up, took my hand, and let me off somewhere. A door shut and we were in the pitch black, kissing. I didn’t get too excited, as I had no idea who Brad McCarthy was or what he looked like. At least by this point thanks to Steve LaFlamme I was an experienced kisser. Brad was not, and after enduring a few moments of his slobbering on my face, I said, “We should go back” and fumbled for the doorknob. I sat down next to Cindy, who gave me an odd look, and wiped something off my face with a pizza-stained napkin.

And now came the great day, the first day of high school. I had given up on the hope of miraculously transforming myself into anything but me, yet I still spent hours trying on outfits before I decided to make my East High debut in a cute floral printed baby blue minidress with open sleeves that tied at the wrist in dainty white ribbon bows. Thanks Mom. I gathered up the required huge fabric-covered navy binder filled with lined paper and colored acetate dividers, lots of sharpened pencils, a fistful of pens, and a slide rule. The backpack still had not been invented.

While I had been looking for love at the Deeps, my family had moved into 101 Hawthorne Road, a stately five-bedroom house one block from the high school, so it took but a minute for me to walk to East, leaving childhood behind, ready to start my new life as a full-fledged teenager. I plunged into the cacophonous halls of East, twice the size of my junior high, with thirteen hundred kids streaming in all directions, one-third unbelievably cool Seniors, one third stuck-in-the-middle Juniors, and one-third us nervous Sophomores, who were all anxiously piping up “Hi! Hi! Hi!” to anyone who looked vaguely familiar.

I had advanced classes in math, English, and history, and in each one I was greeted by my old fellow smarty-pants from elementary school, Nancy Erman, as if I were a long-lost sister, a bond forged back when we had combed our troll dolls’ hair together, moved little cars full of peg people around in the Game of Life, and smeared cream cheese and Welch’s jelly on white bread. Nancy had progressed in junior high to Queen Bee status, and had her own coterie of popular girls. She had a generous spirit and insisted that I was one of her gang, and suddenly, as if I had been touched by a fairy godmother’s wand, I was a member of the cool girls.

First I had to deal with an unforeseen and unfortunate predicament. As Nancy scooched over at the cafeteria table to make room for me, I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned to see a boy whose face was peeling away. I blinked, looked away, and tried to sit down as quickly as possible. From behind I heard, “I didn’t recognize you with your glasses. It’s me, Brad McCarthy.” Brad had severe psoriasis, his skin was patches of red and white, with flecks sheering off from his eye lids and lips and landing on his shirt. Nancy, who would have nicely shaken hands with a leper, looked up, smiled and chirped, “Hi Brad!” before going back to her sandwich. I wondered what it was that Cindy had wiped from my face, and took myself off to the girls bathroom, with Brad yelling behind, “Gay! Gay! I thought we could…”

I spent my first week of high school hiding behind doors and running into the bathroom before Brad got the message and left me alone, although he did give me the hangdog look every time we passed in the hall for the next three years. I was not that desperate, even though Nancy and most of the other girls in my new circle had boyfriends.

My magical transformation had happened, just when I had given up believing. I was finally one of the popular girls. We called ourselves T.H.E. Gang and were as loyal to each other as the Foreign Legion, the Musketeers, or the U.S. Marines. Nancy was our leader, tall, smiley, freckly and friendly to even the most outcast of our fellow students. Teachers and parents adored her. Nancy’s closest friend was Paula Rivers, The Pretty One, with the face of a Disney heroine, a heart-melting smile, and long Breck blonde hair.

You did not have to be pretty to be in our gang, as evidenced by my acceptance, with my weirdly thick glasses and hair that had decided to go from mousy blonde to rat brown. You could have a beaky, bumpy nose or be as plump as Mama Cass. It didn’t matter what you looked like as long as you were quick to laugh, brave, eager to drink until you were legless, and steadfastly loyal; if you were willing to lie to cover up your friend’s whereabouts (“Yes Mrs. Haubner, Gay spent the night at my house.”), and showed up on the spot when needed, ready to help a girlfriend organize her pants so she could squat and pee in the snow.

These girls taught me how to be a friend and how to accept friendship, always with a whole heart, and I have expected and received nothing less from all the women in my life who have chosen to call me pal.

Tucked under Nancy’s wing I was escorted into this band of sisters, acknowledged as The Smart One, even by Nancy, who still bested me in math. Wendi Carlson was The Crazy One, who set her underpants on fire lighting farts and was the first girl in Duluth history to hop on the ladder of a moving train, ending her short, drunken ride with a tumble that left just a few bits of gravel embedded in her knees. I loved Wendi, even though her mother banned me from their house after I shouldered the blame for the scorched undies Wendi had thoughtlessly tossed in the clothes hamper. I was happy to do that far, far better thing, as Wendi was on the verge of being grounded until graduation, due to previous misdeeds.

In our gang there was none of the catty, petty behavior girl cliques are famous for. There were hysterical giggling fits and shared tears over duplicitous boyfriends. We borrowed clothes and forgot to bring them back. We played hairdresser, and took turns botching up each other’s hair, starting with Wendi using pinking shears to trim my bangs and ending with a hair coloring disaster: instead of the sun-streaked locks shown on the box of dye, Betsy Strauss ended up with big polka dots of orangey blonde in her hair. There were also matching splotches on several of my mother’s white towels. At parties we held back each other’s hair while we puked out bright orange Tango, a disgusting pre-mixed screwdriver, then scrubbed our faces with clean Minnesota snow before going back inside. We even pierced each other’s ears, using an ice cube, a potato, and a sewing needle sterilized in a wooden match for three seconds, which is why my earrings are crooked.

We slept over en masse at my home, taking over the empty bedrooms on the third floor, or at Nancy’s, whose elderly parents went to bed reliably at seven. We gorged on take out cheeseburgers and fries from the London Inn and swapped secrets and confessions until the last girl passed out in her sleeping bag. Best of all, at any home that was temporarily parent-free on a Friday or Saturday night, there were those illicit boy-girl parties I had only heard of, fueled by Tang, Boone’s Farm, sickly sweet booze siphoned off by Linda Lewis from her parents’ extensive and untouched collection of Bols after-dinner drinks, and for the boys, cans of Fitger’s beer Paula spirited away from the back room of her dad’s liquor store. Eventually all the lights would be turned off in the basement or the rec room and couples would disappear into dark corners. I sipped water-downed cream de cacao, put records on the hi-fi, and waited for a boy to sit next to me, until I gave up and went home, well before my curfew of ten o’clock, alone, drunk, and utterly happy.

North Country Girl: Chapter 23 — A Global Citizen Goes to the Deeps

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

If there was anything my mother hated, it was a mopey girl lounging on the couch with a magazine or book, sighing and pointedly not helping with housework. So she signed me up for a four-hour summer class at Woodland Junior High on Global Citizenship. The class was led by two serious young men who spent a lot of time boasting that they regarded us not as students and teachers but as equals; we were all partners in this amazing learning experience. They were do-gooders: they encouraged us to spend the afternoons with them as they canvassed for Fair Housing, knocking on doors and trying to explain to puzzled housewives that they should display the blue and white Fair Housing sticker on their front door to show that they would happily rent to black people. No one in our neighborhood rented out rooms in their home, and there was a dearth of black people to rent to. Our teachers gave us all Fair Housing stickers for our own doors; my mother immediately tossed it in the trash, muttering something about uppity Negros.

What were we supposed to learn in this summer class? To this day I have no idea.

From eight to ten, we played a weird model UN game. We were broken up into countries by lot. Each country had a round table with a small flag stuck in the middle and six to eight kids sitting around it, squabbling about who got to be President and who Minister of War. I was Ambassador to the UN and made regular trips to the big square table at the front of the room that proudly displayed a large blue and white flag that stood for unity and peaceful intentions.

Each country started with the same population and resources, it was up to us to decide whether we wanted to grow wheat, mine coal, trade with other countries, build cities, raise taxes, hold elections, or invade a neighboring country. The first few weeks of this were mildly entertaining; there were kids from other junior highs so there were new boys to yearn for. The rules were extremely complicated and required continuous hashing out and interventions by the teachers to resolve. Every day at ten we had to fill out mimeographed forms indicating what we as a nation had accomplished. The teachers took these forms and spent hours correlating them with the help of an overstuffed binder filled with the different formulae and outcomes for this very weird role-playing game. Each morning at eight, there were typed sheets waiting for us on our table, telling us if our country was deep in debt, had an unhappy populace, raised enough wheat to trade for iron, or had captured a foreign capital. This game, meant to teach us peaceful co-existence, was like Esperanto, well-intentioned but impossible to learn and pretty boring.

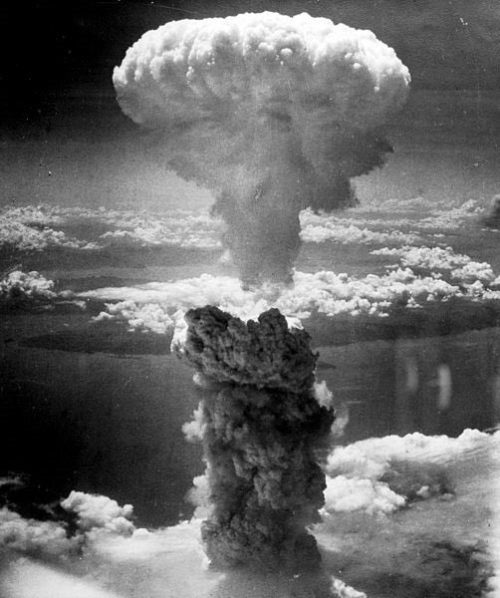

We soon figured out that the most fun we could have was declaring war on each other. Speeches were made, bombs were dropped, ploughshares hammered into swords. Funny insults were traded between countries, under the disapproving eyes of the two young teachers. The next day the papers on our tables told the sad tale that we had destroyed the earth. We got a short, head-shaking lecture on how we were not following the spirit of the game, striving for world peace and a better life for our people, and were a disappointment to both teachers. Thankfully, this was not real life, the world would be resurrected, and the game could start over again. The second round, we wasted no time in even glancing at our agricultural outputs, called up the atomic bombs immediately, and ended the world in a matter of days. At that point, one of the teachers broke down completely, tore the papers up, and announced that the class was over.

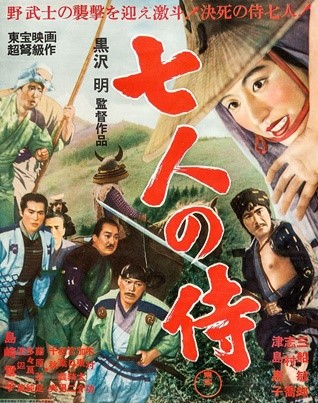

I wasn’t sad about the end of the stupid game, but by blowing up the earth twice, we had also killed off the second part of the class. From ten to twelve, the teachers huddled together over the binder and each country’s scrawled mimeographed sheet while we kids sat in a darkened classroom and watched movies, movies I had never heard of, that had definitely never made it to the Norshor or Granada theaters. Whoever selected the movies did a hell of a job. We saw Japanese movies: Yojimbo and The Seven Samurai. Italian movies: Juliet of the Spirits, Woman in the Dunes, Rocco and his Brothers. We saw The Seventh Seal, Nothing But a Man, and for some reason, The Good Earth, I guess as a nod to China. The movies were shown in a darkened classroom, one of the teachers appearing half way through to change the reel. At noon (or later, if it was a Kurosawa film) I would emerge blinking into the bright summer sunshine, more determined than ever to find a way out of Duluth and into the world. I felt as if I were stranded on an island, craning my neck and squinting over at another land close enough for me to almost make out its wonders, but impossible to swim to.

While my mornings were filled with world destruction and foreign films, my afternoons were gloriously unstructured. Cindy and I were still close, though she was spending more and more time practicing cheerleading, determined to make the East High junior varsity squad. She wanted me to try out with her, but I was too proud of my proto-hippie identity and too aware of my physical shortcomings to even consider a future as an East High Greyhound cheerleader.

At this point my father showed an unprecedented interest in my social life. “You should be friends with Mary Ann Stuart” he ruled, and drove me over to Northland Country Club himself to spend time with Mary Ann, the golf pro’s daughter. My dad must have owed him money. Mary Ann had been another shadowy figure in my life, appearing for a week or two in the summer around the Northland pool from her home in Clearwater, Florida, where she lived with her mother. But this summer she was to spend the entire time with her father, in a small rustic cabin on the country club grounds. Summer days are long in Duluth, and Mary Ann’s dad was out on the golf course from seven in the morning to seven at night. Mary Ann and I had the unheard of luxury of an entire house to ourselves. Put two 14-year-old girls in an empty house and they will have a single goal. The first thing Mary Ann said to me was, “Let’s go find some boys.” Mary Ann threw a cotton button-up shirt on over her bikini top and cut-off jean shorts, a look I copied every day that summer.

This was the official girl’s outfit at the Deeps, the best place to find boys, boys who were swimming and tanning and showing off. On a sunny day in Duluth, when the thermometer hit 75, the Deeps at Lester River were a teen wonderland, boys and girls, half-naked, checking each other out, arranged by the dozens on both banks, or waiting to make one of the Deeps’ death-defying leaps.

Despite everyone knowing someone’s second cousin who had cracked his head open on a discarded refrigerator lurking at the bottom of the Deeps, teenage boys ventured higher and higher dives, clinging one-handed to birch saplings before flinging themselves off the jutting cliffs. I was scared of the refrigerator, a white ghost just visible beneath the tannin-dark water, and stuck to the lower jumps well away from the Frigidaire. But one time in a desperate effort to get a boy to notice me, I worked up the nerve to launch myself off the 40-foot-high railway bridge spanning the Lester River downstream from the Deeps. My courage sprang from my near-sightedness; Mary Ann held my glasses so I couldn’t see how far below the river was. The impact tore my sandals apart and I had to walk back to Mary Ann’s shaking and barefoot.

Besides death from misadventure, the Deeps was also famous for smoking, beer drinking, necking, and even petting. Good girls from nice families, Cotillion girls, did not go to the Deeps; I knew better than to ever let slip to my parents that I spent almost every day there. And if I had not been in the company of Mary Ann Stuart, I would never have been brave enough to venture to the Deeps. Cindy was horrified at my daring.

But Mary Ann knew how to talk to boys, who talked back to her large breasts. I had heard Northland Country Club pool mothers cluck about Mary Ann’s “early development,” and she continued to develop. I learned from Mary Ann what you really needed to get a boyfriend and it was not a winning personality or a cute dress or Yardley lip gloss. My breasts were barely big enough to justify wearing a bikini top, but I benefited from the halo effect given off by Mary Ann’s Playmate-worthy chest.

Boys would wave and call out “Mary Ann!” before they made their terrifying leaps into the river. Boys would offer Mary Ann Tareyton or Old Gold cigarettes and Mary Ann would smoke them. Boys would ask Mary Ann about life in exotic Florida. I would stand to the side and try to look interesting.

Sometimes Mary Ann would pretend to be mad at one of her suitors, and I at least got to talk to a boy, even if all he wanted was to know was how to get Mary Ann to pay attention to him again. Mary Ann would spot us whispering together and say later, “I think he likes you,” and I would sigh, wishing it were so.

Mary Ann finally made her selection from the worthy contenders: Dave Arsenault, tall for his age, a Cathedral High football and hockey player, and a famous Deeps diver. By the beginning of July he had achieved a nut brown tan, which set off his dreamy white-toothed smile and his thatch of dark hair, just long enough to be cool, and soon to be cut down to a crew cut by his football coach.

As the sun dropped between the trees on the other side of the river, Mary Ann said, “Dave, you want to come over to my house?” Dave did, and he and Mary Ann vanished into her room, while I lounged on the creaky, dusty couch, paging through old golfing magazines before giving up and going home.

And just like that, Mary Ann and Dave were boyfriend and girlfriend, and I was the third wheel. This was an unacceptable situation to Mary Ann; she ordered Dave to find a boy for me. She was a real friend.

I ended up with Steve LaFlamme, another Cathedral High hockey player and a knock-off version of Dave Arsenault, but still way too cute for a girl of my middling looks, a girl with smaller than average breasts who wore weird glasses. Steve just ambled back to Mary Ann’s house one afternoon with us; when Mary Ann and Dave disappeared into her bedroom, Steve sat down next to me on that saggy, scratchy sofa. I watched, terrified, as his head loomed in closer and closer to mine, until our faces were smashed together. Oh my god I’m being kissed, what is he doing with his tongue, it feels huge, I can’t wait to tell Cindy, where is my own tongue suppose to go? I disentangled myself to take off my glasses, which were digging into the side of my head, and thinking that now Steve would get to admire my true beauty. Steve took one look, screwed his eyes shut, and went back in for the kill.

By the time Dave emerged from Mary Ann’s bedroom, collected Steve, and waved goodbye, my lower face was achy and sore. I didn’t care. My first kiss and was what we did necking or making out? Did this mean he was my boyfriend? I guess I liked him, even though he never actually talked to me, outside of asking, “You’re going to East?” I wasn’t sure he knew my last name so how was he going to call me? Dave called Mary Ann every evening.

That night I mentally kicked Napoleon Solo, Mick Jagger, and Robert Plant out of bed and fell asleep imagining Steve telling me how much he liked me, Steve kissing me, Steve reaching over the table at Somebody’s House to hold my hand, Steve kissing me, Steve and I frolicking in the pools at the Deeps, Steve kissing me…

An Ordinary House

For many of us the home that’s fondest in our hearts is one we remember from childhood. For me it was the first actual house I ever lived in—a rental the family moved into when my father, a textile salesman, was transferred to Baltimore from New York. Up until then, we’d been living in an apartment in the Bronx, also a rental. I’m not sure co-ops and condos even existed then. If they did, Mary Ann and I sure didn’t know about them.

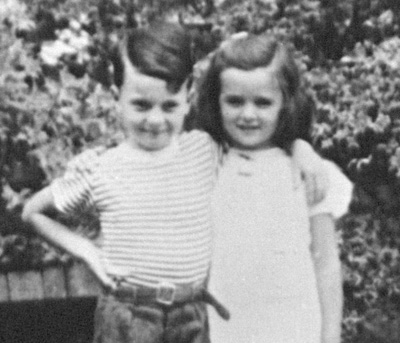

Mary Ann is my sister. We were both 8 years old at the time, but we weren’t twins. We were what everybody called “Irish Twins,” born in the same year; I in January, and she in December. My folks talked up this move to Baltimore, telling us we’d be living in a place with a lawn. This seemed pretty exotic to us, and we were really looking forward to that. On the day we moved in, while the moving men were unloading furniture from the van, Mom looked out an upstairs window and saw the two of us lying on our backs on the little postage stamp of a lawn, looking up at the sky. But the front lawn didn’t look small to us. It looked like the country. Imagine our delight to find out the place had a backyard, too. Also small, the backyard provided a little more privacy and enough room for playing tag and hide-and-seek with neighborhood kids. We’d bounce a rubber ball off the steps, use a bamboo clothesline stick as a pole vault, and hide Easter eggs when that season came. Big enough for games and growing a victory garden—mostly tomatoes, pumpkins, and radishes, as I recall. And sure enough, victory did come, didn’t it? We did win World War II. Around that time, our baby brother was born, and sharing his growing up would be a big part of our life story, too. While there would be other houses we’d call home, our first home on Edgewood Road is the one that always comes to mind.

The house had a big front porch with a swing on it. When it rained, we’d hang out there with neighborhood kids, tell each other movies we’d been to, scene by scene, and sing rounds like “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” That porch was where Mr. Shapiro used to leave the dozen or so copies of The Saturday Evening Post that I used to deliver to neighbors. I remember laughing a lot at the cartoons, and sometimes those Norman Rockwell covers were funny, too. I never thought I’d be in The Saturday Evening Post. Later, I’d also delivered The Baltimore Sun. All those things I associate with the outside of that particular house on Edgewood Road.

Inside, of course, was the kitchen. I remember Mom putting newspapers on the kitchen linoleum and spraying us both with calamine lotion, head to toe with a flit gun, when we accidentally rolled around in some poison ivy. In that room, I also remember the more pleasing aroma of dinner being cooked. They say smell is the strongest sense memory. I can still smell mushrooms being sautéed and the aroma of split pea soup simmering on the stovetop. Whatever the dinner was, the family would always eat it every night in the dining room when Dad was home. Afterwards, Mary Ann and I would help with the dishes: I’d wash, and she’d dry, or vice versa. There was a lot of singing going on, too.

In the living room was the piano, which always got a workout. Mom played “That Old Silver Moon Shining Down Through the Trees.” Both Mary Ann and I were taking piano lessons from Miss Matilda Dietch so there was much practicing. Usually we played a duet; “Voices of Spring” is one I remember as well as “Tales from the Vienna Woods.” When the piano wasn’t playing, the radio was. No TV of course in those days. But to this day I can tell you who sponsored which shows: The Shadow was Blue Coal; Jack Benny, Jell-O; and The Lone Ranger, Silver Cup Bread.

The expression “Home Sweet Home,” to me, is the memory of voices and faces in that place on Thanksgiving and Christmas, of friends and relatives—grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and a little dog named Inky.

It’s not the rooms of that house I think of so much as what went on there. It’s always the people; the singing, laughing, and joking—and occasionally quarreling and crying. Quite often, actually, come to think of it. You go back and look at a house all these years later, and it seems so different now, much smaller than you remember. And you realize that if it’s still there at all, it has to be basically what it was. It’s us who have changed. It’s not the brick and mortar, the shape, or size that matters. It’s the people; it’s the life. Old Edgar Guest had it right when he wrote, “It takes a heap o’ livin’ in a house t’ make it home.”