Russians Go to War to Win at Home

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S01260/CC-BY-SA)

In 1915, Russia was just starting to emerge from centuries of autocratic rule. Czar Nicholas II had recently broken with the Romanov dynasty’s 300-year-long tradition of autocratic rule to give the people a limited voice in their governing. His unprecedented move was a result of Russia being soundly defeated by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War. The loss shook Russians’ faith in their czar, his ministers, and his military officers. The people began calling for reform. At a peaceful protest in St. Petersburg, the czar’s troops fired on a crowd of petitioners. Hundreds were killed and, as news spread, protests and strikes erupted across Russia. In the end, Czar Nicholas permitted an assembly, called the Duma, which had limited lawmaking power. But the government’s underlying corruption and unresponsiveness remained, and public resentment simmered.

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H28740/CC-BY-SA)

Then came World War I. Russia mobilized its army to aid Serbia. But the government’s true reason for entering the war, according to a Post reporter in St. Petersburg at the time, was to regain its hold over its people.

“Report has it that never in the history of Russia had the autocracy been so close to tottering,” wrote Mary Isabel Brush. The czar’s ministers and his brother the grand duke believed a call to arms would revive patriotism and loyalty among the people. Maybe a good war would reunite Russia and put an end to all the talk about representational government.

The working class, however, had other ideas. They welcomed another war because they’d gained so much in the last one. When Brush asked workmen in the shops why they were fighting, the Duma was part of everyone’s answer. “Their legislative body was, to them, the final result of the war preceding, and they felt that the present strife would bring greater power to them.

“Let Russia win, and she thought her autocracy would be stronger than in the days of its strength. But the workingman thinks not. He says, let Russia win, and it will mean more rights for him. He will then be in a position to command. One of the large questions is: Which of them knows what he is talking about — the autocracy or the workingman? The answer will be heard round the world.”

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H28740/CC-BY-SA)

As it turned out, neither the autocrats nor the workers knew what would happen. The element that would soon dominate Russia wasn’t even part of Brush’s consideration. While she may have overlooked the power of Russia’s radical element, Brush was correct in her conclusion: the answer — the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 — would definitely be heard round the world.

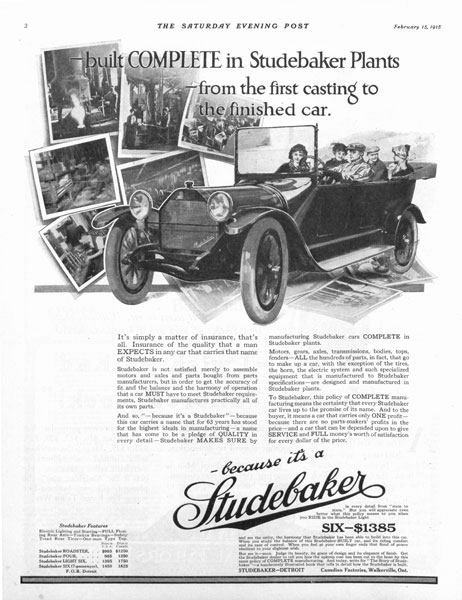

Step into 1915 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post February 13, 1915 issue.