The Birth of Washington, D.C.: 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the Nation’s Capital

President George Washington signed the Residence Act 230 years ago this week on July 16, 1790. The Act provided for the establishment of both a temporary and permanent seat of government for the young United States. The temporary seat moved from New York to Philadelphia, but the new and permanent seat would be built by the Potomac River. The site became Washington, D.C., and as famous as it is, there are still facts that many Americans may not realize about how it came together, and what it might yet be. Here are ten things you didn’t know about the nation’s capital.

1. It’s in the Constitution

Article I of the United States Constitution immediately concerns itself with the establishment of the legislative branch and the creation of the House and Senate. In Section 8 of Article I, the powers of Congress receive some fleshing out (like the laying and collection of taxes, war declaration powers, post office creation, etc.). Clause 17 of that section also gives Congress the ability to create a federal district for the nation’s capital with the phrase “To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of Government of the United States.”

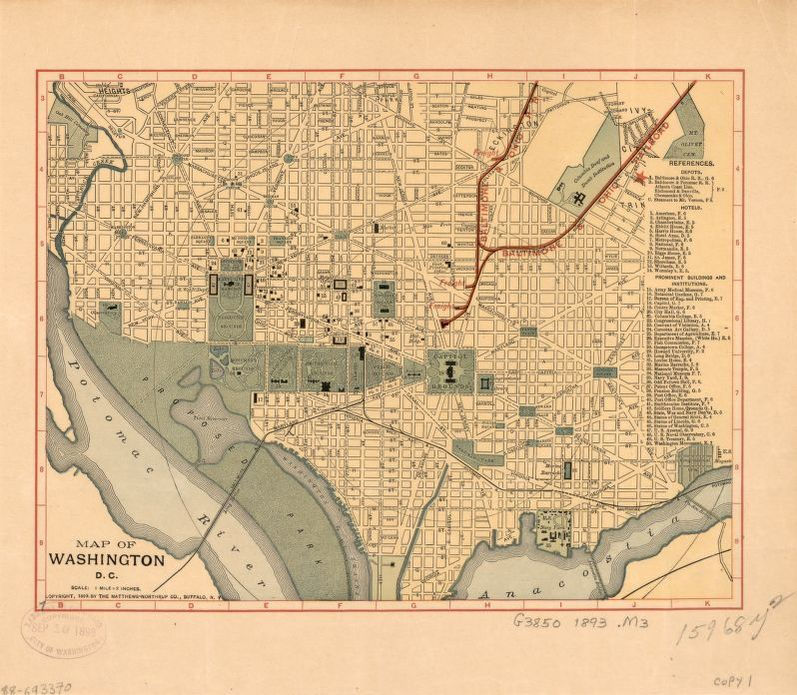

2. Maryland and Virginia Donated the Land

The language in the Clause that indicates “by Cession of particular states” meant that pre-existing states would donate the land for the new federal district. Maryland and Virginia donated the land that comprised the 10×10 mile square, which was also stated in the Constitution.

3. The Residence Act of 1790 Made It Official

Signed 230 years ago this week by President George Washington, the Act fixed the future seat of government at the Potomac site. A deadline of December 1800 was established for the new capital to be in use. The Residence Act also gave Washington the authority to appoint commissioners to run the project.

4. Why It’s the District of Columbia

Surveying and construction was soon underway. The appointed commissioners chose a name for the new federal city and district on September 9, 1791. The city itself was named after the first president (who had, after all, signed the Residence Act into law). The federal district was named the District of Columbia for reasons that run from obscure to uncomfortable now. For quite some time, “Columbia” was a nickname for America as a feminine form of Columbus (which is, of course, a controversial topicThe song “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” was even a contender for the official National Anthem. So, the city is called Washington, D.C. with the city and district in the same way that you would identify a city in a state as, for example, Indianapolis, Indiana.

5. The District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801 Covered the Details

Congress finalized the fine points with the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801. An organic act determines the necessary pieces of how a territory is defined, including what body has authority over it. Being a federal district, Washington, D.C. is overseen by Congress. The Act also created two counties within the district, Alexandria County (south and west) and Washington County (north and east), each with a court. As the district encompassed the pre-existing cities of Alexandria and Georgetown, they hewed to their already established local laws. However, as the district, including those cities, fell under federal control, Congressional representation was removed since the cities were no longer part of the states that they were originally in. The fact that D.C. residents pay taxes without representation has long been a bone of contention and is one of the primary drivers behind the “D.C. Statehood” movement.

6. John Adams Was the First President to Live There

John Adams was the second president, serving from 1797 to 1801, but he was the first to live in the White House in Washington, D.C. Adams and his wife, Abigail, moved into the House in 1800 before it was even completed. In the widely acclaimed HBO mini-series John Adams, which won 13 Emmys and four Golden Globes, the arrival of John and Abigail at the White House was dramatized. The scene makes a point of the irony that enslaved people built the “free” nation’s capital; while John and Abigail Adams were not slave owners themselves, they occasionally paid slaves owned by other district residents to do work at the property. The scene is reportedly accurate in its depiction of the conditions around the White House; while the building proper was finished, the surrounding area was largely muddy and uncleared upon their moving in.

7. The War of 1812 Wrecked the Place

The War of 1812 ran from June of that year until 1815, pitting the young United States against Great Britain. In 1814 on August 24, British troops made it to Washington and set about burning the city. The Capitol building suffered tremendous damage, including the loss of the then-current 3,000 volumes of the Library of Congress. The White House burned, as did the U.S Treasury, the Department of War, and other buildings. Fortunately for what was left, an enormous storm broke loose over the city and the pounding rain put out many of the fires. The storm touched off at least one tornado in the city, and the British withdrew to their ships, which were taking damage from the storm. All told, the British occupation of D.C. lasted just over a day, but much of the city, particularly the government buildings, would have to be completely rebuilt in the aftermath.

8. D.C. Had Famously Bad Water

A Killer in the White House. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Saturday Evening Post)

As documented in a Post story from 2019, early D.C. had no sewer system. The White House itself would have no running water for years; water was still being carried in by buckets before the fire in 1814. The Jefferson administration had looked into pumping in water as early as 1807, but no running water came until 1833. Unfortunately, there would be several problems with that over time, as the video above documents.

9. The Smithsonian Institution Started with a British Donor

Washington, D.C. is also home to The Smithsonian Institution, which was founded in 1846 and continues to be administered by the U.S. government. The name comes from James Smithson, a British scientist who made the original donation for a national museum. The Smithsonian as a whole includes 19 museums and galleries, most of which have enormous digital collections and videos that you can see at their sites online.

10. They’re Still Building Monuments

One could be forgiven for thinking that monument-building in D.C. has come to an end, but the city continues to add monuments and memorials to important people and events. The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial is still scheduled to open in September of 2020. Among the projects currently in the works is a National World I War Memorial that will be located in Pershing Park and memorials to Gulf War/Desert Shield/Desert Storm veterans, Native American veterans, and both free and enslaved Black Americans that served in the Revolutionary War. The Korean War Veterans Memorial is also slated for a “wall of names” like the one already featured at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.