Gallery: Mass Transit Through the Years

To accompany “The Looming Crisis in Mass Transit” from our Jul/Aug 2012 issue, we’ve highlighted some of our favorite transportation-themed Post covers. We welcome your comments below.

The Looming Crisis In Mass Transit

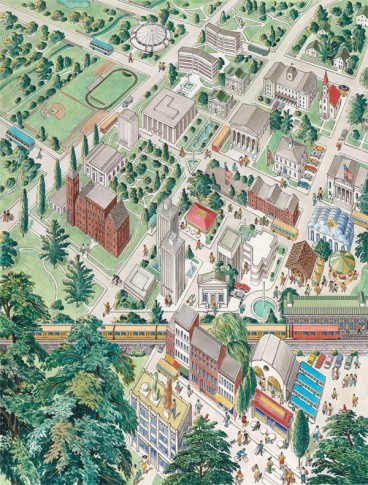

In Normal, Illinois, the construction of a new bus-train station revitalized a neighborhood in decline. (Illustration by Rodica Prato) Click here to view more Post covers featuring mass transit.

Over the past 50 years America made massive public investments in its highways—hundreds of billions of dollars in the interstate system alone. And largely because of that investment, cities and suburbs have grown into sprawling, disconnected clusters, largely dependent on the automobile. But America is changing, and it’s time to rethink the way we travel. “We have to change that and give people more options,” says John Robert Smith, president of Reconnecting America, a nonprofit in Washington, D.C., that advises local leaders on transportation planning.

What’s the problem with car travel? Not to put too fine a point on it, but our current network of roads and more roads (with a piddling number of trains and buses along the margins) is not sustainable. Today, 91 percent of Americans commute to work in a car, usually alone. The daily cost of fuel for cars is a staggering $1 billion-plus. Then there is conservation: All told, American drivers burn roughly one-quarter of the world’s oil. [See also What Government Needs to Do by Jim Oberstar, former chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.]

Demographic trends also reflect a country reconsidering its settlement patterns and transportation networks, particularly in light of an expected population increase of more than 100 million new citizens over the next 40 years. Much of the population—from retiring boomers and young people alike—will be closer to city centers where mass transit is available.

Petra Todorovich, director of America 2050, a national urban planning organization in New York City, says when you look ahead a few years, better mass transit will be sorely needed. “We can’t just keep building more highways and creating more sprawl,” Todorovich says.

What is essential for the success of mass transit is not just building the infrastructure itself, but connectivity. Travelers need to get from point A to point B quickly and efficiently. But for mass transit to work well, those same travelers also need to be able to switch easily from a taxi, a bus, a ferry, an airplane, or a train in a matter of a few steps to continue on to point C. In Europe, trolleys and high-speed trains run into the airports and the switch is accomplished in a short escalator ride. It’s seamless, even intuitive.

In America, not so much. “We are 30 to 40 years behind Europe and Asia,” said Smith, who adds that the big push for mass transit will have to come from state, city, and county governments and filter up to the federal level.

Despite the obstacles to rebuilding America’s mass transit system—and there are quite a few obstacles—there are also a few bright lights. A few months ago, I went to California to write a piece about the proposed bullet train that would run between San Francisco and Los Angeles. There’d been a storm of political fighting over funding—the cost of the train may exceed $50 billion—and battles over where to put the right of ways, but it appears California will start laying track in late 2012. The 220-mph train would be one of the largest public works projects ever attempted in the United States, but California has a history of doing big and gutsy infrastructure projects.

While the complete bullet train is at least a decade off, California is moving ahead on mass transit. In 10 days of traveling between its major cities, I avoided renting a car, even calling a cab. For such a supposedly car-centric state, the connectivity was remarkable. For example, beginning in Oakland, I traveled to Sacramento on the Capitol Corridor, a train operated by Amtrak but subsidized by the state.

From there, I caught another corridor train, the San Joaquin to Bakersfield where I easily stepped on an express bus to downtown L.A. On the city’s metro system, I rode the Blue Line light rail out to Long Beach, the Red Line to Hollywood, and then city buses to see friends in Wilshire and Silver Lake.

To reach San Diego, I took the Pacific Surfliner which runs hourly out of L.A.’s Union Station, and then a trolley to my hotel in Old Town. Over the next few days, I was on Sprinter, Coaster, and Metrolink—all commuter trains—and the Surfliner again. And when it was time to fly home, I caught an express FlyAway bus from Union Station to LAX.

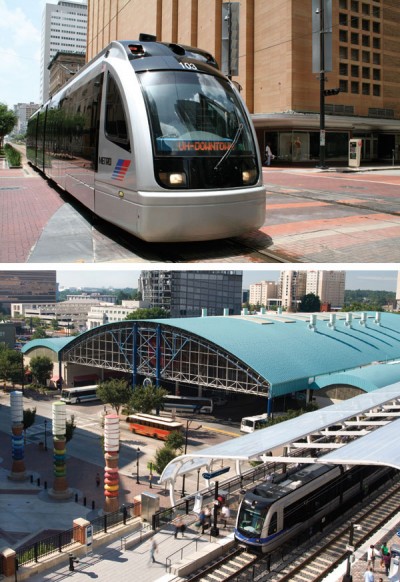

What is happening on the West Coast is being repeated around the country. New light rail systems are being built or expanded in Salt Lake City, Denver, Dallas, Portland, Seattle, Atlanta, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and Charlotte. Cities, such as L.A., are actually restoring service where decades ago they literally ripped out street car tracks to make room for cars. But it’s not just trains. Buses operating on natural gas, hybrid engines, and even overhead electrical wires are redefining city bus service. And in rural America, counties and other entities are finding ways to bring mass transit—typically bus or van service—to people who can’t afford cars or are unable to drive.

Mass transit is very much in the public eye, which is not surprising when one considers rising gas prices, highway congestion, unsustainable suburban sprawl, and an aging population. In 2011, Americans took 10.4 billion trips on public transportation, the second-highest annual ridership since 1957.

“For a long time, most transit riders were captive riders. They couldn’t afford a car and had to use the bus,” says Todorovich. “Now we are seeing more people using it as a lifestyle choice.”

Lifestyles matter, too. Many experts see America’s embrace of handheld devices and the desire to be connected electronically as another factor favoring mass transit over driving. Drive a car and you can’t or, at least, shouldn’t text. “If you are on a train or bus, you can stay on your iPad or smartphone,” adds Todorovich. And buses and trains that are Wi-Fi equipped make connecting that much easier.

It’s a big step from wanting or needing mass transit, to actually building it. With little clear direction from the feds, the solutions will be different for different localities. Which brings us to the bus-versus-train argument. Many urban areas are choosing to build light rail—even though improved bus service can be just as effective and would be a ton cheaper, says Professor G. Scott Rutherford, director of the TransNow Regional Center at the University of Washington in Seattle. That’s because buses run on infrastructure already in place—namely roads—and they are able to easily go off that right of way into neighborhoods, such as suburbs. Building new right of ways for trains is difficult and expensive, especially when trying to retrofit rail into highly urbanized environments.

But many cities see light rail as the only way to lure people out of their cars, says Rutherford. “There’s a rail bias,” he says. “Hey, I love trains, too, but an honest analysis in many communities would show that trains are not as good as buses.”

He points out that the common image of the loud and smoky city bus is a thing of the past. Buses today are cleaner, quieter, and quite efficient compared to automobiles.

Just as important, despite my successful experiment in California, in most American cities, bus stations, train stations, and airports were not built with an eye toward connectivity. Most such travel hubs are separated by several miles—the only transport option is an expensive cab ride. Even where there are attempts at connectivity, they are often problematic. In Milwaukee, Amtrak’s commuter train stops near Mitchell Airport, but passengers have to board a shuttle bus and then be deposited at the front of the airport. At the Seattle-Tacoma (Sea-Tac) Airport, the new light rail train only gets within 1,200 feet of the baggage area. The train station is located in the parking garage.

The obstacles range from turf wars to simple lack of foresight: “You could put the bus right in the front of the terminal, but the airport doesn’t want to interfere with single passenger cars picking up passengers. And because it sells parking, it doesn’t want to sacrifice spaces to get the train closer,” Rutherford says. “A lot of problems are jurisdictional. Transit crosses regional and political boundaries and there are competing interests.”

Gas Should Be More Expensive

If we want to reduce fossil fuel consumption, I say, we should raise the price of gasoline to $7 a gallon.

Reason: Today this country burns through 21 million barrels of oil per day, 60 percent of which is imported. Only with some shared economic pain will we ever change our habits.

High gas prices will force us to think before we drive. It will encourage mass transit use, car pooling, and the sale of more fuel-efficient cars.

The auto industry will not suffer because it has learned that it can charge more for cars that are cheaper to build if those cars have a few luxury touches.

Individuals will spend more dollars on gasoline, even factoring in the reduced usage, but American motorists are notoriously inefficient and have traditionally done an awful job of planning their errand runs.

Average families will feel the pain, but, in my view, a move to less-expensive beer and other consumer goods should go a long way toward softening this inconvenience.

Drivers who own gas-guzzling pickup trucks will be motivated to carpool or take mass transit where it’s available.

Because mass transit is not as widely available as it should be, much of the gas price increase would be allocated to improving our railroads and creating more bus lanes.

As for diesel fuel, I would leave it at its current price of $4 a gallon. Yes, that will encourage the sale of diesel vehicles, but despite the hue and cry of environmentalists about all things diesel, those cars today are just as fuel efficient as the gas-burning kind.

Large diesel trucks, of course, must remain because they deliver the majority of the goods we consume.

My proposition is simple enough. Higher fuel prices mean less fuel consumed, and that means cleaner air and reduced dependence on imported fossil fuels.

A tough proposal? Sure. But Americans are a tough people capable of making hard decisions when it comes to spending.

The opinions expressed in “The Contrarian View” do not represent those of The Saturday Evening Post.