Maypole Memories

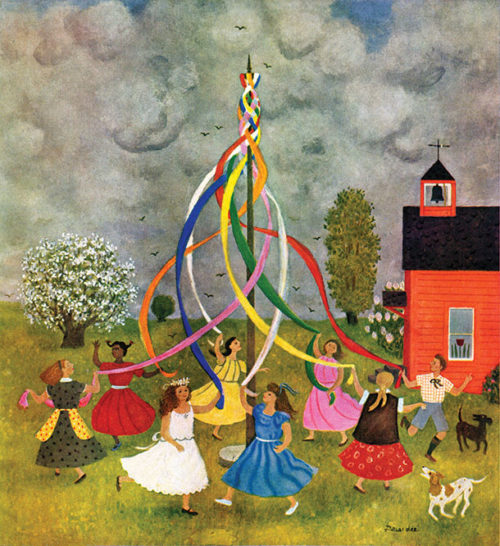

Several years ago, our town built a new elementary school, everything from the old school was hauled to the new, except for the playground maypole, which had been removed after flinging some kid into the next county. The maypole was the centerpiece of May Day, a holiday no longer recognized in our town after people noticed the communists were holding parades that day and deep-sixed it. But Mrs. Conley, my fourth-grade teacher, wasn’t cowed by capitalists or communists, so marched us to the maypole, where we welcomed spring. The most agile boy trailing streamers of ribbon would shinny up the pole, tie them off at the top, then slide back down. We would take the ribbons in hand, extend them straight like spokes on a wheel, and parade in a circle, earths of humanity orbiting our maypole sun. Mrs. Conley would recite from William Wordsworth’s poem “Lines Written in Early Spring”:

The birds around me hopped and played,

Their thoughts I cannot measure:—

But the least motion which they made

It seemed a thrill of pleasure.

By then it was lunch and we would file inside to the cafeteria where Mrs. Sisk had been cooking all morning. In concession to spring, our thrill of pleasure was ice cream for dessert, eaten with flat wooden spoons that left splinters on our tongues. I sat next to Stevie Wright, who was lactose intolerant long before the phrase had been coined. For the sake of his health, I would eat his ice cream, too.

May Day signaled the first day of recess baseball. Mrs. Conley would carry the bats and balls out to the playground, then leave us to divide into teams and play. Today, adults insert themselves into the game to coach and umpire, to keep things on the up-and-up, but Mrs. Conley believed in free-range baseball, in letting us settle matters ourselves, first yelling and screaming, then lowering our voices, giving here, taking there, seeking common ground. Workers of the world uniting, just like the communists.

I was chosen near the end, an obvious burden to any team, so while playing right field would drift unnoticed to the maypole. Other boys would be there, running in circles, lifting off their feet, riding the currents of centrifugal force like the hopping birds of Wordsworth’s poem.

Doris Lee

The Saturday Evening Post

May 4, 1946

Occasionally, a boy would let loose and take flight, landing in a bloody skid on the gravel that covered the playground. Today, playgrounds are covered with shredded rubber to ensure soft landings, but back then we understood the gravel as a metaphor, that high flying eventually resulted in rough landings.

When I was in high school, I dated a girl who lived a block from the school. In the spring of our romance, we met there and swung, side by side, hardly talking. She was shy and I was scared, knowing talk was expected. Instead, we would see how high we could swing, arcing back and forth until the chains were parallel to the earth. The chains would sag and we would feel weightless, descending until the chains caught tight, jerking and twisting us. Now those lines written in early spring are faded, replaced by fresher lines since written.