Do You Really Want Socialized Medicine?

In the following article, Post writer Steven Spencer examines legislation—spearheaded by President Truman—to nationalize U.S. healthcare. We think you’ll find it interesting how closely the arguments in this 1949 report echo today’s healthcare debate.

[See also: “Fixing Our Healthcare System” from our Sep/Oct 2012 issue.]

May 28, 1949—For the eighth time in 10 years the American people are being urged to let the Government pay their doctors for them, with money collected from the American people. The system is called compulsory health insurance, and the theory is that everybody who doesn’t have enough medical care today will surely have it tomorrow, because the Government will see to it that he does.

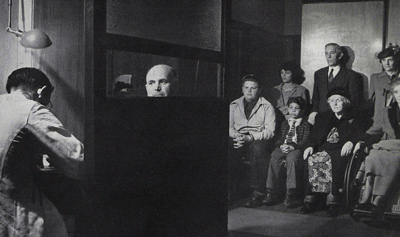

Between theory and practice there is a tremendous gap, much of which is currently being filled with arguments. Many of them fall in a familiar groove, but they are pitched this time against a more substantial background than heretofore, namely, the actual experience of 48 million residents of Great Britain under a comprehensive National Health Service. The scheme entitles everyone in Britain, visitors as well as citizens, to all medical, dental, and hospital care at the expense of the taxpayers.

Curiously, Britain is being called to give testimony for both sides of the American controversy. Many of those who want compulsory health insurance cite the British plan as a shining example for us to follow. Their opponents, including the American Medical Association, point to the same program as a warning of dire things to come if we adopt any Government-directed system and propose, instead, an extension of voluntary health insurance, with financial help from state and Federal governments.

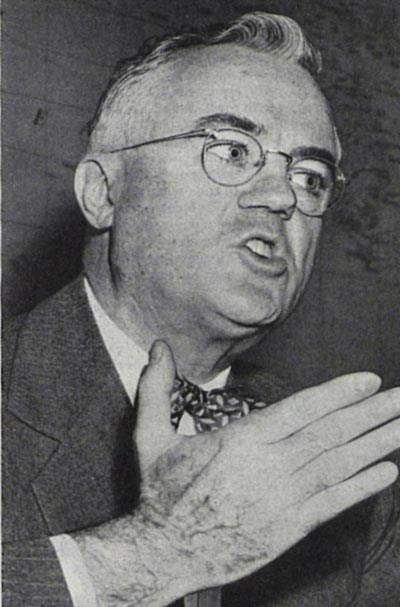

What is the story? Should Britain’s 11 months of nationalized medicine—socialized if you use the broad definition of that term—cause us to embrace or reject the compulsory plan so insistently advanced by President Truman, Federal Security Administrator Oscar R. Ewing, and the Wagner-Murray-Dingell group in Congress? In this article we shall look for an answer by examining the Administration’s health insurance plan in the light of the British experience.

The explanation for the two-way character of the British evidence is that, where there are as many people of intelligence and good will as one finds in England, no plan for the care of the sick will be a 100 percent failure—at least not at first. Most people are willing to give it a sporting chance. Even the British doctors, while swearing under their breath—and sometimes audibly—at Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan and the scheme which he and Parliament pushed through over their opposition, are trying sincerely to make it function. And certainly the majority of the working people—whose purchasing power has for years been much below that of Americans at comparable jobs—welcome a form of medical care supported mainly by taxes on the middle- and upper-income groups.

Yet it is highly significant that nearly everyone with whom I talked in England had some reservations about the scheme. People felt that too many were abusing it and thus jamming the traffic in the doctors’ offices, that many physicians were being overworked and underpaid, that dentists and eyeglass dispensers were making a killing, that the administrative machinery was cumbersome, slow, and inefficient. Even one of the government’s own regional officers remarked that “most people would not be so mad as to take over such a large thing all at once.”

The temptation to buy the whole package at one time is very great in this period of increasing dependence on government. In fact, the first danger in any proposal for government medicine lies in the ease with which it can be glamorized. Like the bodybuilding courses that come with a pair of 25-pound dumbbells, it looks magnificent on paper. Unfortunately, the result is usually far short of the pictorial promise in the advertisement. The dumbbell system has one advantage, though. If, after a few weeks, you are dissatisfied with your rate of deltoid development, you can stow the dumbbells in the attic and forget them. State medicine is not so easily shucked off, once you have installed it.

A good many of the British people admit they bought Bevan’s system a bit too hastily, and they now confess to a feeling of disillusionment. They had been won over by the bright promises of everything for everybody. Now that the scheme has been in operation almost a year, their enthusiasm has dimmed.

Three North of England women expressed this reaction in strikingly similar terms. Said a hospital superintendent, “I was for the plan, but this transitional period sometimes makes you wonder if it is worth while.” Then she added, “But I do think it will work out eventually.”

A miller’s wife, formerly a nurse, remarked, “I thought beforehand that nationalization of the hospitals would be good, but now that I’ve seen how it works out, I think I was wrong. … The county hospitals are operating 10 automobiles where they were running only one before. … Everybody feels he must get what he can out of the government before someone else does.”

And a woman doctor, brushing a wisp of blond hair out of her eyes as she signed a sheaf of certificates and orders, confessed, “I was for the plan, but now we family doctors seem to be in danger of becoming simply form fillers and traffic officers, shunting people to this hospital or that specialist.”

Some of the British criticism of the National Health Service is bound up in a growing dislike of the whole idea of the welfare state, in which food, housing, fuel, and now medical care are at least partially provided by the government.

One of England’s leading medical scientists, head of an important government council, feels so strongly on this point that he told me, “If I were a young man in England today, I would get out and go somewhere else. I don’t object to seeing that the poor get enough to eat,” he said, “but why should I be taxed to the limit to put bread in the mouth of the employed worker, who should work hard enough and be paid enough so that he can buy his own food without heavy subsidies?” The comment is frequently heard in England that so much subsidizing is destroying the people’s initiative.

While the British health program differs in details from the compulsory health-insurance measure of Senators Robert F. Wagner and James E. Murray; and Congressman John Dingell; and their cosponsors, the two plans are cut on the same basic pattern. Both spread the wings of government-directed medicine over all or nearly all of the population. Both lean heavily on central government authority. And both are compulsory in that all wage earners and taxpayers must pay for the services, whether or not they approve them or make use of them.

The scope of the new Wagner-Murray-Dingell bill is not quite so broad as that of Bevan’s plan, since the former would cover only those under Social Security, with a few additional categories. But the trend is to broaden Social Security to take in almost everyone. “We aim to have everyone who is the head of a family become taxable,” explains Mr. Dingell, “so that he and all his dependents under 18 would be entitled to benefits. … Why, this is the most liberal proposition in the world.”

Many of Mr. Dingell’s opponents think his bill is far too liberal. Why, they ask, should tax-supported medical care be offered to everyone, the $10,000-a-year man as well as the family getting along on $1,500? The coverage of government medicine is one of the crucial issues of the whole controversy. Both sides agree that no one who needs medical care should be denied it because he is unable to pay. The opponents of compulsory insurance maintain that it is in the American tradition that those who are able to care for themselves and their families should not lean on government for help. The Wagner-Murray-Dingell group maintain it is too hard to determine who is able to care for himself and who isn’t, and that the easiest and fairest way is to make medical care freely available to everyone on the basis of compulsory wage deductions.

Mr. Dingell recalls that his own family lacked means for adequate medical care when he was a boy. “I contracted diphtheria,” he said, “at a time when it cost 25 dollars a shot for anti-toxin. My family couldn’t afford that, and I guess I was one of the very few who pulled through without it.”

He declares that he has seen people refused admission to hospitals because they had no money, and he cites the case of a man brought in from the street in Detroit with third-degree burns. “Because no one, including the policeman who brought him in, could insure the fellow’s bill,” Dingell said, “the patient was turned away from one hospital and had to be carried clear across town to the city receiving hospital. Under a system in which every hospital knew the Government would pay every patient’s bill, this would not have happened.”

The Doctor Glares at State Medicine

In 1944, doctors worried that socialized medicine, as proposed in the Murray-Wagner-Dingell bill, meant ruin for their profession. If readers doubted this, Frederic Nelson encouraged them to ask their family physicians.

[See also: “Fixing Our Healthcare System” from our Sep/Oct 2012 issue.]

December 9, 1944—Your recent doctor’s bills probably shared the envelope with a leaflet warning you against “socialized medicine.” The leaflet, sponsored by the National Physicians Committee, explains that, if anything like the Murray-Wagner-Dingell Social Security Bill passes, doctors will become state jobholders with no more personal interest in your tonsils than could be expected of the clerk of bills at the city hall. Friends of the medical-care sections of the Wagner Bill protest that the National Physicians Committee doesn’t really represent the docs, but the fact remains that your family doctor, who is wearing himself out by his efforts to spread medical care as far as he can, thinks his number is up.

Right or wrong, this is what most doctors think, and if you doubt it, the thing to do is ask your doctor. He will probably talk your arm off, but after all you get a $250 amputation for nothing. I can testify that there is no better way to outlast the other patients in the waiting room of a doctor’s office than to stop saying “Ah” long enough to introduce some such line as this: “Doctor, I heard on the radio the other night where a fellow was explaining that only reactionaries were against this Wagner Bill.” I have tried this topic on all sorts of doctors, from orthopedists to the plain general practitioner (G.P. Joe, as I suppose he will be known from now on). The result is practically always the same. My researches indicate:

- That American doctors are against socialized medicine or any modification thereof which subordinates them to bureaucrats, makes them salaried officials, or interferes with their professional standards.

- That American doctors are definitely interested in making medical care available to more people, and in plans to pay doctors’ bills on the insurance principle—provided such plans are nonpolitical.

The fact that any group should want anything else is a complete mystery to the doctor. He is driving himself at top speed to meet the demands on him, and is baffled by sociologists who think he could trot from bed to bed faster, if only the Federal Government would take over. Caught off guard, he is likely to give you something like this:

“You pay for your groceries, give the landlord his monthly check, and pay the undertaker a fabulous sum to bury you. But just let the doctor identify a strep infection in time, fix you up with the proper sulfa drug, and send you a bill for $28, and down you sit to write to your congressman demanding that doctors be sovietized and medical expenses subsidized by the state. I don’t get it.”

You say, if he hasn’t shut your face with a clinical thermometer: “But, doctor, there are a lot of people who simply can’t pay medical bills. Furthermore, even the average middle-class man with a good salary is knocked for a loop if he is hit by a $500 operation that keeps him from work for a couple of months. Nobody is blaming the doctor or expecting him to support his patients when they are flat on their backs. The problem is to find a way to help people pay for medical care, so that the doctor won’t have to treat the poor for nothing, hoping against hope to land enough rich men who don’t mind paying $2,000 to have an appendix lifted.”

Of course, your doctor hasn’t been listening. He has been waiting for you to stop talking, maybe snapping a nose elevator in the air to calm his nerves.

“You mention the people we treat free in clinics. Do you know what will happen to them under state medicine? In our clinic they get the attention of the best men in the profession. When Wagner and Murray get through with medicine, no doctor of any standing will ever see such a patient. Why? Simply because there will be a fee attached, and you can be pretty sure that some shyster with a brother-in-law at the city hall will grab all those cases.”

“All right, all right,” you interrupt, pushing aside the stethoscope, “but something has got to be done.”

“Sure,” agrees the doc, “but understand at the outset that you are dealing with the services of highly trained professional men and not with something you can dish out over the counter at the supermarket, or, if the customers can’t pay, through the Surplus Commodities Corporation.”

Let’s not assume from all this that the doctor has done nothing to meet new conditions. Actually, he has done quite a lot to put himself on a semi-collective basis. The individual doctor can no longer afford to equip himself with all the expensive machines and gadgets used in modern practice. If he lives in a city, he probably works around a hospital where he can treat his very sick patients and consult with other doctors on cases that puzzle him. If he is a country doctor, he does the best he can. Doctors have for years grouped themselves together to feed an assembly line of diagnosis and treatment without benefit of politicians. The trouble is that relatively few laymen can afford this attention. Some crotchety doctors think the patient isn’t missing much.

Because modern medical care is expensive, we have free clinics, special arrangements for the middle-class poor, and a gradual extension of treatment in hospitals at standard prices. Recently, a writer in Medical Economics protested that hospitals were providing too much medical care administered by salaried doctors and thus presenting a menace worse than “socialized medicine.” Obstetrics at flat rates, X-ray treatments, salaried anesthetists, and tonsillectomies “packaged to include surgical as well as hospital costs in one fee” were among the marketing schemes complained of. “It is time the medical profession prepared to defend the stand to which it gives lip service,” said the article. “It takes more than strong language at the AMA meeting once a year to turn the tide. We are approaching a day when physicians will be merely a class of skilled laborers, readily hired and fired by their community medical centers.”

To the man in the doctor’s waiting room this sounds like the corner grocer worrying about the supermarket. The layman is indifferent to the dilemmas of doctors because he isn’t familiar with them. At any rate, he was before the National Physicians Committee began its campaign to tell the customers how state medicine would affect them. The committee reports that its surveys reveal a trend away from socialized medicine as a result of the family doc’s mild words in his own behalf.

The patients never wanted state medicine anyway, but only some sort of prepayment scheme which would make it possible for a man of modest income to pay his own medical bills. Actually, the doctors want this too. They welcome patients who carry health insurance and many of them encourage and participate in group-insurance and group-medicine plans. But they don’t want a system, like that proposed in the Wagner Bill, in which the qualifications of doctors, educational standards, and the right to specialize in practice are determined by a board headed by the Surgeon General.

Because he isn’t much on politics, the doctor messed up his case pretty badly at first. Consequently, he got himself sued under the antitrust laws and pictured to the untutored as a leech who translates the oath of Hippocrates into English as “Never give a sucker an even break.” Actually, every man knows that his own doctor is a faithful and hard-working practitioner whose personal convenience is always at the mercy of his most capricious patient. We all know doctors who perform endless labors for nothing and treat the indigent as faithfully as their few wealthy customers. But so bad have been medical public relations that advocates of state medicine have succeeded in creating a doctor who doesn’t exist at all—a cold, calculating, selfish, reactionary politician whose object is to keep a very few people just well enough to pay exorbitant bills, but not healthy enough to dispense with the doctor. That picture, however, is changing. People are coming to find the bedside manner of Wagner, Murray, and Dingell a little unctuous.

The doctors have more to do—and I’m passing this along to the next doctor who treats me, if the door is handy—and that is to understand a little more fully than some of them do now that the public is not much interested in socializing them, but is genuinely concerned with the costs of medical care as a real problem in the lives of most people. Pari passu, the social planners may as well climb down from their high horse and interest themselves in the development of medical care on evolutionary lines, and by doctors, instead of a device to make doctors into political functionaries, thereby making the lot of the patients, including the poor ones, worse instead of better.