The Medical Insurance Mess: How We Got Here

We shouldn’t be surprised that healthcare insurance has become a contentious issue. For most of our history, it developed with little planning or regulation. True, the U.S. has one of the most advanced healthcare systems in the world, but it has also become the most expensive.

Today, according to Forbes, the rising cost of healthcare is Americans’ chief financial worry.

And yet, for all we are paying, we may not be getting the best healthcare for the money.

A 2014 study found that the U.S. has consistently ranked lowest behind 11 leading European nations for effectiveness, safety, responsiveness, access, efficiency, equity, and life expectancy.

The problems with healthcare insurance reach back to the early 20th century. The first medical insurance policies were issued in 1890, but Americans didn’t generally adopt the idea. They preferred to pay for medical services as needed and avoid expensive hospital care if at all possible. They were so successful that, by the 1920s, hospitals in many cities were struggling to stay alive.

In 1929, an official at Baylor University hospital in Dallas noted that Americans annually spent more on cosmetics than on healthcare, but they didn’t mind their cosmetics expenses because the costs were small and continual. So Baylor hospital developed a program that collected a small monthly fee, on the scale of a household expense, to cover future healthcare needs. The program, which was offered to public school teachers for 50 cents a month, proved successful and eventually became the Blue Cross plan.

During the Depression, healthcare costs in many cities became unaffordable. The Roosevelt administration proposed a public-sector solution: a national health-insurance program similar to Social Security. However, the idea was strongly opposed by the American Medical Association, which feared that insurance providers would dictate how doctors would treat patients.

Employers became the primary source for medical insurance during World War II. Struggling to find enough qualified personnel, employers normally would have offered higher salaries to lure the best workers. But Washington had put a cap on wartime salaries. Fortunately, the IRS ruled that medical insurance could be added to employment packages without violating the wage ceiling. One company after another began offering health insurance.

When the war ended, President Truman tried another public-sector solution: an optional public health-insurance plan that would cover major medical expenses. Again, the AMA opposed the idea, along with the Chamber of Commerce, which labeled it socialism.

When it became clear that government health insurance would never pass, trade unions began bargaining with businesses for employer medical insurance. The IRS encouraged the idea by giving employers a 100% tax deduction for insurance costs. Medical benefits were also tax-exempt for employees.

This arrangement proved very attractive to businesses and workers. The number of Americans with health insurance rose 700 percent between 1940 and 1960, when about 70 percent of Americans had medical insurance. But three groups weren’t covered by employer-based healthcare insurance: the poor, the elderly, and the chronically sick. In 1966, President Johnson proposed Medicare and Medicaid to extend medical coverage to these groups.

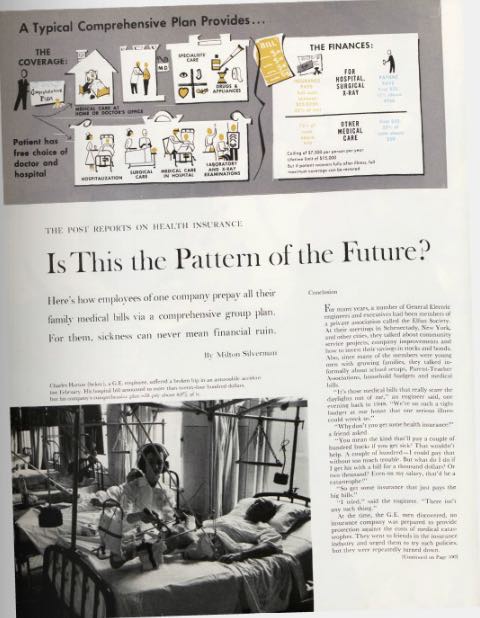

This combination of private and public insurance programs might have served America indefinitely had costs remained static. But, as the graph below shows, healthcare costs rose steadily, and sharply.

Over the years, politicians have suggested public programs to make healthcare more affordable.

- Senator Ted Kennedy proposed a single-payer plan.

- President Nixon came up with a plan of mandates and incentives for employers.

- President Clinton took Nixon’s approach and added financial help for people who couldn’t afford insurance.

In 2010, President Obama managed to get his controversial Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, dubbed “Obamacare,” passed. It was intended to improve health outcomes, lower costs, and make healthcare more accessible. Since its passage, this public program has been bitterly opposed by conservatives.

Opponents argue that the federal government can’t require Americans to pay into a healthcare program.

But this wasn’t the first government-run mandatory-contribution healthcare system in the U.S. In July 1798, Congress ordered the Collector of Customs to obtain 20 cents a month from every American sailor “to provide for the temporary relief and maintenance of sick or disabled seamen.” The system, which operated the government’s Marine-Hospital Service, remained in operation until 1870.

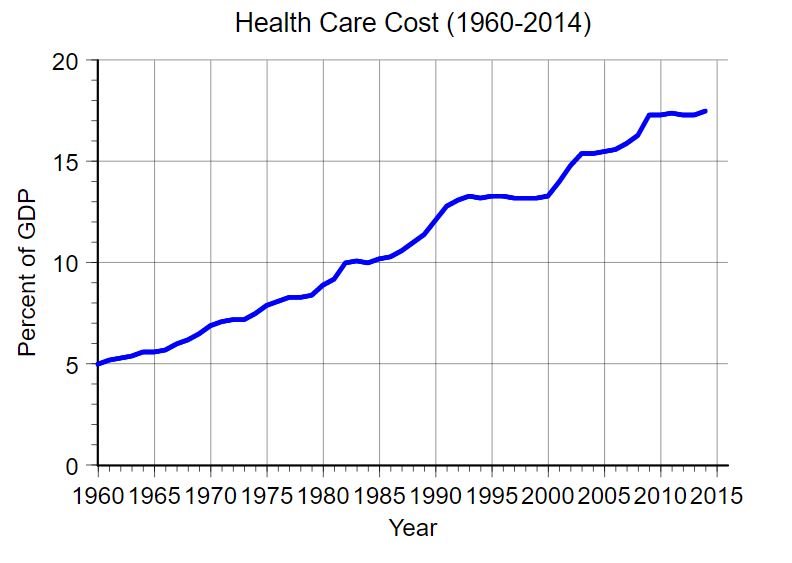

That information comes from “The Post Reports on Health Insurance,” a three-part report by Milton Silverman that the Post published in 1958. It offers today’s readers a picture of the medical industry before Medicare and Medicaid. Even then, there were concerns about “the upward soaring pattern” in healthcare costs, which were rising at 5 percent a year.

The series also explains how the insurance industry, in an attempt to hold down healthcare costs, monitored for signs of insurance fraud and overbilling. The final installment asked, “Is This the Pattern of the Future?” and described a new approach to medical insurance that should seem familiar to readers today: the policyholder pays a deductible and co-insurance fee for their care. In return, the insurance company covers the remainder of all expenses.

Obviously, the answer to Silverman’s rhetorical question was “yes.”

Featured image: Queen of Angels Hospital, Los Angeles. Three out of every four patients in this big (502-bed), busy institution are covered by health insurance of some kind.

Photo by Sid Avery