Putting the Mouth Back in the Body

In the 17th century, a barber surgeon ministered to the dental needs of the Plymouth Colony. In the 18th century, goldsmith and ivory turner Paul Revere, a hero of the American Revolution, constructed false teeth in Boston. Tooth decay and toothaches were seen as inevitable parts of life, and care of the teeth was widely considered a mechanical concern.

By the turn of the 19th century, science and specialization were transforming many aspects of Western medicine. A growing emphasis upon clinical observation and an increasing array of instruments — stethoscopes, bronchoscopes, laryngoscopes, endoscopes — brought a sharper and narrower focus to the study of disease. Physicians and surgeons, increasingly working together, developed new approaches to treating specific ailments of the heart, the lungs, the larynx, the stomach, the bowel.

They left teeth to the tradesmen.

But Chapin Harris, who began his career as an itinerant dental practitioner, led the effort to elevate his trade to a profession. Within the span of a year, between 1839 and 1840, Harris worked with a small group of others, including Horace Hayden, a Baltimore colleague, to establish

dentistry’s first scientific journal, a national dental organization, and the world’s first college of dentistry.

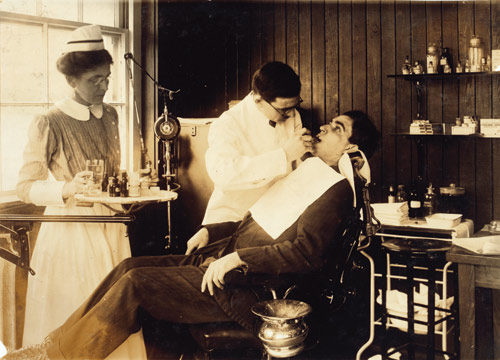

Dental students learned the mechanics of drilling and filling teeth and constructing dentures. They learned to perform extractions. Then they went out to practice in the villages, towns, and cities of a growing nation.

In 1880, Ohio dentist Willoughby D. Miller traveled to Germany to work in the laboratory of physician and scientist Robert Koch. Koch had traced the cause of anthrax to a specific bacterium. In two more years, he would present his discovery of the microbe responsible for tuberculosis, a killer of millions. Koch helped transform the study of disease.

Willoughby Miller studied oral bacteria on a microscopic level and began to see the mouth as the vector for all manner of human suffering. Bacteria invaded the bodies of people and animals by way of their mouths, causing deadly epidemics such as cholera and anthrax. But the mouth was not just a passive portal for illness. Miller saw it as an active reservoir for disease, a dark, wet incubator where virulent pathogens were able to multiply.

Leading American and British physicians concurred: The human mouth was a veritable cesspool. Aching teeth and inflamed tonsils were teeming with newly discovered germs. Physicians ordered dental extractions, tonsillectomies, and the removal of other suspect organs for the treatment of disorders ranging from hiccups to madness — for arthritis, angina, cancer, endocarditis, pancreatitis, melancholia, phobias, insomnia, hypertension, Hodgkin’s disease, polio, ulcers, dementia, and flu.

Vaccines were sometimes concocted and administered in concert with dental extractions in the belief that they would counter the effect of the germs that were released from the roots of the teeth. The English writer Virginia Woolf was preparing for such an ordeal in May 1922 when she wrote to her friend Janet Case. “The dr. now thinks that my influenza germs may have collected at the roots of 3 teeth. So I’m having them out, and preparing for the escape of microbes by having 65 million dead ones injected into my arm daily. It sounds to me to be too vague to be very hopeful — but one must, I suppose, do what they say,” she wrote.

In the United States, the physician Charles Mayo, of the Mayo Foundation in Rochester, Minnesota, acknowledged that some of his patients had complained about being left toothless. But he was convinced that the oral cavity was the seat of most illness. “In children the tonsils and mouth probably carry 80 percent of the infective diseases that cause so much trouble in later life,” he noted.

“Total clearance,” the removal of all the teeth, remained widely recommended.

In the face of the mass extractions, dentist and dental x‑ray innovator C. Edmund Kells stood up for tooth preservation. In an address in 1920 before a national dental meeting held in his hometown, New Orleans, Kells denounced the sacrifice of teeth “on the altar of ignorance.” He demonstrated the usefulness of his x-ray machine in examining teeth and the power it gave dentists to offer second opinions and to resist the orders of physicians to extract teeth needlessly. Kells urged “exodontists” to “refuse to operate upon physicians’ instructions.” And he contended “that the time has come when each medical college should have a regular graduate dentist upon its staff to teach its medical students what they should know about the oral cavity.”

But it could be difficult for dentists to defy physicians. The two professions not only distrusted each other — they inhabited separate worlds. The tensions and lack of communication hurt patients, concluded the respected biological chemist William J. Gies in his major 1926 report on dental education in the United States and Canada for the Carnegie Foundation. Gies was troubled by the entrenched disdain for dentistry he found among medical professionals. “Even research in dental fields is regarded, in important schools of medicine, as something inferior,” wrote Gies, who himself had been deeply immersed in the study of oral disease at Columbia University.

Gies firmly believed that dentistry should be considered an essential part of the healthcare system. He called for the reform of dental education, for closer ties between dental and medical schools and between the two professions.

“Dentists and physicians should be able to cooperate intimately and effectively — they should stand on a plane of intellectual equality,” Gies noted in a speech to the American Dental Association. “Dentistry can no longer be accepted as mere tooth technology.”

The mass extractions and surgeries continued through the 1930s. As microbiology advanced, however, the research underlying them was held up for closer scrutiny. Untold millions of teeth had been extracted, and the diseases the extractions were intended to cure persisted.

The growing availability of antibiotics in the 1940s offered new tools for fighting infections. But Gies’ calls for closer ties between dental schools and medical schools met with resistance. Many dentists rejected the idea. In 1945, an effort to integrate the faculties of the dental and medical schools at Gies’ own institution, Columbia University, was strongly opposed by the dental faculty. The dentists’ act of defiance was applauded by the editors of the Journal of the American Dental Association. “The views of the majority of dentists in the country cannot be misunderstood on the question of autonomy. The profession has fought for, secured, and maintained its autonomy in education and practice for too many decades to submit now to arbitrary domination and imperialism by any group,” they wrote.

Today, nearly all American dental and medical schools remain separate.

In addition, cooperation has also been complicated by another disjoint between the two professions: the fact that dentistry has historically lacked a commonly accepted system of diagnostic terms. Treatment codes have long been used in dentistry for billing purposes and for keeping patient records, but the long absence of a standardized diagnostic coding system for dental conditions has inhibited the understanding of the workings of oral disease, some researchers have said.

A uniform, commonly accepted diagnostic coding system would represent a major shift of emphasis in dentistry, “a move from treatment-centric to diagnostic-centric” care, said UCSF dentist Elsbeth Kalenderian, who spearheaded a dental coding initiative as a professor at Harvard. Efforts are now underway to put such a system into place. The integration of medical and dental records will become increasingly important as researchers such as Robert Genco, from the University of Buffalo, continue with their work. Over the past three decades, Genco has focused upon periodontal disease and its relationships with wider health conditions.

Years of study have led Genco and his team to a sense that obesity, periodontal disease, and diabetes are all “syndemically” bound by inflammation. Other researchers are more conservative in their assessments. The diseases are deeply complex. But the clues of biology will eventually bring oral health into the larger understanding of health, and dental care into the wider healthcare system, Genco has predicted. The gap between oral healthcare providers and medical care providers will need to be bridged, he said in an interview. “We all have the same common basic sciences. We all train in a similar fashion. But still the professions are separate. We dentists don’t look too much at the rest of the body, and the physicians don’t look at the mouth.”

Science has become a leading force in integration, Genco explained. “It’s getting us to look together at the patient as a whole. It’s a two-way street. Physicians and dentists really have to integrate in their management of the patient. So it is bringing the professions together. Putting the mouth into the body.”

This article appears in the March/April 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Copyright © 2017 by Mary Otto. This excerpt originally appeared in Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America, published by The New Press Reprinted here with permission.