Can a Retired Vaccine Company Executive Change How We Think About Pandemics?

As the United States passes another grim milestone with more than 100,000 deaths due to COVID-19, one scientist thinks his idea could have saved lives. And may yet save lives in pandemics to come.

In a small village in France, Dr. David Fedson has been working for the past 16 years to promote a cost-effective strategy of using generic drugs to combat a pandemic.

“If we ran trials on promising drugs before the pandemic and found this approach to treatment didn’t work, well, so what? I was wrong,” Fedson says. “But if, after the pandemic, the research confirms that this approach actually does work, and then we look back at all those people who died unnecessarily, we’re going to feel very bad indeed.”

Drugs such as statins (a cholesterol lowering medication) as well as ARBs and ACEIs (blood pressure medications) are the drug types that he advocates running clinical trials on, as stated in his 2020 medical paper, “Hiding in Plain Sight: An Approach to Treating Patients with Severe COVID-19 Infection,” and other published work. While not averse to vaccines, he sees the mounting death toll as a case in point that to fight a pandemic there needs to be a medical option on “day one,” when the virus first starts spreading.

“The only way to effectively confront a pandemic is to figure out a way to use what we already have,” Fedson says. “Drugs that are generic, inexpensive, and that doctors use every day in their practices.”

Fedson is a retired professor of medicine from the University of Virginia who also served as the medical director at Aventis Pasteur, a European vaccine company. He saw the weakness of a vaccine-only approach to an influenza pandemic back in 2001 when he was instrumental in establishing the Influenza Vaccine Supply International Task Force.

“The whole purpose of the task force was to get the companies we worked for — and the top-tier executives running them — to pay attention to the fact that someday we would have an influenza pandemic,” Fedson says. “And it became quite apparent to me that the global capacity to manufacture pandemic vaccines just wasn’t there. By the time the vaccines would become available, it would be too late.”

Dr. Alice Huang, a virologist and former Harvard Medical School professor who was involved in developing a vaccine for HIV, confirms that an approved vaccine for the coronavirus will take time.

“We all really need something sooner rather than later, but in my experience with making a vaccine…it takes a long, long time,” Huang says. “And when you read about people saying that it would take about a year to 18 months, that is if everything goes perfectly right.”

Fedson recounted an early career experience treating cholera patients in India, not by targeting the pathogen, but focusing on keeping the patients alive long enough so they could overcome the worst effects of the disease.

“I spent three months on the Johns Hopkins Cholera Unit in Calcutta as the team fine-tuned a formula to rehydrate cholera patients, a breakthrough that has saved tens of thousands of people ever since,” Fedson says.

What made it effective is that the rehydration treatment could be lifesaving not just for cholera patients, but also for those suffering from severe diarrhea caused by other diseases. Regardless of what brought on the severe diarrhea — it could be a virus, shigellosis, or any number of other infections — the same treatment would keep the patients alive long enough until their own defenses took over and the diarrhea stopped.

The same concept of focusing on the well-being of the host instead of defeating the pathogen may be applied to treating COVID-19 as well.

In the case of COVID-19, when the immune system becomes compromised, its response can be too strong, causing a self-destructive form of inflammation that has been dubbed the “cytokine storm.”

Cytokines are small chemical messengers that tell the immune cells of the body to become activated, so they are ready to fight the virus. As is increasingly evident in some COVID patients, when that inflammation occurs in the alveoli of the lungs — the air sacs critical for delivering oxygen throughout the body — it can cause acute respiratory distress (ARD) and death.

Dr. Brian Ward, a professor at the Centre for the Study of Host Resistance at McGill University, who specializes in immune system response, says that a virus usually does not kill its host, but that COVID-19 is behaving atypically.

“It’s a weird virus; it’s not like many of the other viruses that we deal with,” Ward says. “Even though we’re closing in on one and three-quarter million people infected in the U.S. and five and one-quarter million worldwide, we do not yet have a clear idea of why some people seem to walk through the illness and other people get into real trouble really fast. And certainly, the idea of the body’s reaction, the so-called cytokine storm theory, is one of the hypotheses for that late inflammatory reaction in the lungs.”

Worldwide, there are currently more than 337,000 confirmed fatalities due to COVID-19 according to the World Health Organization’s May 24, 2020 coronavirus situation report, with the numbers likely to rise.

Instead of making the virus the primary target, which is what vaccines and antivirals do, Fedson says the top priority is to find a cost-effective generic drug — or a cocktail of drugs — that will reduce some of the worst consequences of the immune system’s overly zealous response to the virus and save lives.

“We’re talking about a way of treating people with acute critical illness due to any cause, and it can be a pneumonia, ARDs, it can be bacterial sepsis, it can be viral diseases, it can be lots of things that cause people to be hospitalized and get into ICUs,” he says. “The wonder and the beauty of it is that we’re using generic drugs that are available to people in Bangladesh, just as they are available to people in Boston.”

In the midst of the pandemic, Fedson’s idea may finally be gaining traction. Investigators at numerous U.S. universities — as well as in several countries outside the U.S. — have undertaken trials of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), a kind of cardiac medication that Fedson says might be especially effective when “repurposed” for use in pandemic illness. ACEIs and statins are being studied as well.

Two of the most important and innovative of these trials on ARBs are now underway with COVID-19 patients at the University of Minnesota trialing the blood pressure medication Losartan. As an ARB, Losartan blocks activity on a receptor site that raises blood pressure. It is possible that blocking this receptor will also diminish inflammation and reduce damage to the lungs of COVID patients.

“Losartan has an established safety profile and is readily available,” says Dr. Chris Tignanelli, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota Medical School overseeing the trials and administering the drug to both in-patients and out-patients. “We wanted to test a readily available, cheap, FDA-approved generic drug with potential efficacy against COVID-19.”

Tignanelli was initially swayed by promising reports written by doctors in China who observed “a one-third reduction in lung injury” in SARS-infected lab mice who were given Losartan. The current trials are financed in part by the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator Funds — a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation initiative.

Dr. Michael Puskarich, the other doctor running the University of Minnesota’s randomized control trials, also sees potential for Losartan.

“Losartan is different from the other treatments being tested right now — it’s not an antiviral medication,” Puskarich says. “We’re trying to prevent the lung injury caused by the virus that makes it so deadly. We’re trying to turn COVID-19 into an everyday coronavirus, the common cold.”

The cost for a typical regimen of Losartan (14 tablets) is $15. Tignanelli says Losartan most likely will not be a “miracle drug,” but could be used as part of a cocktail of drugs.

“The story probably won’t end with Losartan,” he adds. “I doubt that any single drug is going to be a magic bullet as we’re probably going to need some combination of anti-inflammatory drugs targeting different parts of the immune pathway.”

Drug cocktails are something that hospitals such as St. Luke’s University Health Network in Pennsylvania are administering to their COVID-19 patients. At St. Luke’s, doctors have used a combination of vitamin C, zinc, atorvastatin, and steroids, as well as high-flow nasal oxygen and other pioneering approaches.

“Of course, the concept of using cheap drugs makes perfect sense, even to a random person on the street,” Fedson says, recounting a woman he met on a bus pre-pandemic who agreed it was worth a shot. “Unfortunately, she is not the president of the United States, and she’s not the director of the NIH [National Institutes of Health], or the director of the CDC [Centers for Disease Control], or the director-general of the WHO [World Health Organization]. I wish she were. If she had been, we would be much better off today than we are.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Accidental Invention of the Lifesaving Pacemaker

Wilson Greatbatch — who was born 100 years ago today — was tinkering with an oscilloscope in 1956 when he installed the wrong resistor and accidentally invented the implantable artificial pacemaker.

Greatbatch noticed the device could be altered to drive a heartbeat and realized this was exactly what was needed to replace the bulky, painful pacemaker machines hospitals were using at the time. Patients with so-called “heart block” were suffering blackouts, dizziness, and often death because their hearts’ own electrical impulses could not properly function. By running electrodes directly from his new machine into the muscle tissue of the heart, Greatbatch discovered that his artificial pacemaker could keep a patient’s heart on track indefinitely.

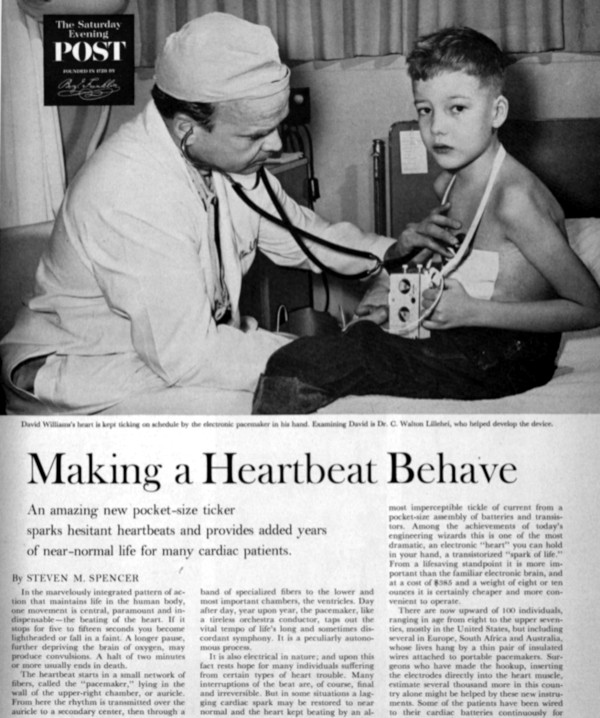

First, the device was tested on dogs, then — after some design improvements — it was ready for human testing in 1957. The medical marvel of “an amazing new pocket-size ticker” was covered in this magazine in 1961 in “Making a Heartbeat Behave.” The implantable artificial pacemaker allowed people with heart problems, many of them children, to lead full, active lives without the fear of constant fainting, or worse. “Among the achievements of today’s engineering wizards this is one of the most dramatic,” writes Steven M. Spencer, “an electronic ‘heart’ you can hold in your hand, a transistorized ‘spark of life.’”

In 1961, there were about 100 people using the new device. Now, about 3 million people in the world have an implanted pacemaker. Greatbatch’s invention was one of the most important of the 20th century, giving a renewed lease on life to millions of people in the decades after his serendipitous discovery. In the 1970s, he went on to develop a corrosion-free lithium battery so that pacemakers could run for a continuous 10 years instead of the previous 2-year lifespan.

The electronics savant worked into his senior years, developing treatment procedures for AIDS, a solar-powered canoe, and a low temperature nuclear fusion reactor. Greatbatch claimed in 2004 that he held more patents — about 150 — than any other living inventor.

Featured image: Photo by Bill Shrout (SEPS)

Cartoons: The Doctor Is In

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Bill Harrison

December 1, 1951

Bernhardt

November 3, 1951

George Smith

September 15, 1951

Galagher

September 8, 1951

Al Johns

July 4, 1959

Bill K

January 5, 1952

Vick Ericson

December 29, 1951

All cartoons: SEPS.

Are We Living Too Long?

Rolf Zinkernagel, a Swiss immunologist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1996, believes that the lifespan of human beings has far exceeded what it was intended to be: “I would argue that we are basically built to reach 25 years of age. All the rest is luxury.” Wealthy older people spend a lot of time and money maintaining their health and postponing death. Dinner-party conversations center on colonoscopies, statins (drugs which reduce blood cholesterol), and new diets. Many Americans who are not doctors subscribe to the New England Journal of Medicine. I have noticed a similar trend in well-off, older acquaintances of mine: health, and its maintenance, has become their hobby.

All quite laudable, but let’s take this trend to its logical conclusion. What are the consequences for society if average life expectancy rises to 100 years, or even more? We face the prospect of an army of centenarians cared for by poorly paid immigrants. The children of these centenarians can expect to work well into their 70s, or even 80s. The world of work will alter drastically, with diminishing opportunities for the young.

What if powerful new therapies emerge which can slow down the aging process and postpone death? Undoubtedly it will be the rich and powerful who will avail themselves of them. Poor people in Africa, Asia, and South America will continue to struggle for simple necessities, such as food, clean water, and basic healthcare. There will be bitter debates about whether the state should fund such therapies. The old are a powerful lobby group and, compared to the young, are far more likely to vote, and thus hurt politicians at the ballot box. Politicians and policymakers mess with welfare provision for the old at their peril. The baby boomers of rich Western countries are now in their 60s and 70s and are aiming for a different kind of old age than their parents. They demand a retirement that is well-funded, active, and packed with experience. They are unfettered by mortgage debt and are the last generation to receive defined benefit pensions. The economic downturn of the last several years has only strengthened their position. They are passionate believers in the compression of morbidity.

But this vision of aging is wishful thinking. Many now face an old age in which the final years are spent in nursing homes. There are several societal reasons for this: increased longevity, the demise of the multi-generational extended family, and the contemporary obsession with safety. None of us wants to spend the end of our life in a nursing home; they are viewed (correctly) as places which value safety and protocol over independence and living.

What are we to do? We will not see a return of the preindustrial extended family; the future is urban, atomized, and medicalized. The bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel outraged the baby boomers with his 2014 essay for the Atlantic, “Why I Hope to Die at 75.” He attacked what he called the American immortal: “I think this manic desperation to endlessly extend life is misguided and potentially destructive. For many reasons, 75 is a pretty good age to aim to stop. Americans may live longer than their parents, but they are likely to be more incapacitated. Does that sound very desirable? Not to me.”

Auberon Waugh (who died aged 61), son of Evelyn Waugh (who died aged 62), once remarked, “It is the duty of all good parents to die young.” Montaigne put it like this: “Make room for others, as others have made room for you.”

Charles C. Mann wrote an essay in 2005 for the Atlanticcalled “The Coming Death Shortage,” which envisaged a future “tripartite society” of “the very old and very rich on top, beta-testing each new treatment on themselves; a mass of ordinary old, forced by insurance into supremely healthy habits, kept alive by medical entitlement; and the diminishingly influential young.”

I am broadly in agreement with Mann that ever-increasing longevity is bad for society, but the problem is this: Given the opportunity of a few extra years, would I take them? Of course I would. There is an old joke: “Who wants to live to be 100? A guy who’s 99.”

Medicine has taken much of the credit, but longevity in developed countries has increased owing to a combination of factors, which include not only organized healthcare, but also improved living conditions, disease prevention, and behavioral changes, such as reductions in smoking.

Interestingly, the maximum human lifespan has remained unchanged at about 110–120 years; it is average longevity which has increased so dramatically. Where do we draw the line and call “enough”? We can’t. John Gray has eloquently argued that although scientific knowledge has increased exponentially since the Enlightenment, human irrationality remains stubbornly static. Science is driven by reason and logic, yet our use of it is frequently irrational. Does this phenomenon have any relevance to my daily work as a doctor? Well yes, it does. Irrationality pervades all aspects of medicine, from deluded, internet-addled patients and relatives, to the overuse of scans and other diagnostic procedures, to the widespread use of drugs of dubious benefit and high cost. Cancer care has been described as “a culture of medical excess.” Overuse and futile use is driven by patients, doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. The doctor who practices sparingly and judiciously has little to gain either professionally or financially.

Many within medicine view with alarm the direction modern healthcare has taken — that spending on medicine in countries like the U.S. has passed the tipping point where it causes more harm than good. We have seen the rise in the concept of disease “awareness,” promoted, not infrequently, by pharmaceutical companies. Genetics has the potential to turn us all into patients by identifying our predisposition to various diseases. Guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology on treatment of blood pressure and high cholesterol levels identified 76 percent of the entire adult population of Norway as being “at increased risk.” This ruse of “disease mongering” (driven mainly by the pharmaceutical industry) has identified the worried well, rather than the sick, as their market.

We cannot, like misers, hoard health; living uses it up. Nor should we lose it like spendthrifts. Health, like money, is not an end in itself; like money, it is a prerequisite for a decent, fulfilling life. The obsessive pursuit of health is a form of consumerism and impoverishes us not just spiritually, but also financially. Rising spending on healthcare inevitably means that we spend less on other societal needs, such as education, housing, and transport. Medicine should give up the quest to conquer nature, and retreat to a core function of providing comfort and succor.

Editor’s note: Would you agree that the way medicine is practiced in America today favors longevity over quality of life? We’d like to hear your opinions for a follow-up discussion to be published in the next issue. Send your comments to [email protected].

From The Way We Die Now by Seamus O’Mahony. Copyright ©2017 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Maritin’s Press.

This is article is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock