Alien Enemies: America’s Persecution of German Citizens During World War I

The news in early March of 1917 wasn’t good. Americans learned that German submarines were going to resume their attacks on all ships heading to England. Just days later, the U.S. government released the text of the Zimmerman Telegram, an intercepted message from Germany to Mexico. If the U.S. entered the war, it read, and Mexico declared war on the U.S., a victorious Germany would force America to return the territories of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona to Mexico.

Even before these news items, American opinion had generally turned against the German cause. It had been Germany, after all, who sank the Lusitania. And it was probably Germany who blew up an island in New York Harbor where the U.S. had been storing ammunition.

Now, as war drew closer, the country was growing more apprehensive about spies and saboteurs working for Imperial Germany. Many Americans suspected their German neighbors of being foreign agents. Pro-war propaganda in the newspapers helped to further demonize all Germans in Americans’ eyes. The public’s fears were shared by the federal government, which pondered how it would handle aliens from an enemy nation.

It was a problem that the U.S. would struggle with in subsequent conflicts.

In “Alien Enemies,” an article from the March 17, 1917, issue of the Post, author Melville Davisson Post describes how Great Britain developed its approach to handling German aliens. Based on Britain’s experiences, he recommends the U.S. take aggressive measures against anyone of German ancestry in America, including stripping naturalized German Americans of their citizenship and subjecting them to military justice. He also urges the forcible relocation of all resident aliens away from areas of military significance.

When war did come, President Wilson signed orders that labeled all Germans in America “enemy aliens.” He barred them from working in or near military facilities or Washington, D.C. This caused so many Germans to lose their jobs that the Labor Department feared a serious shortage of manpower.

All Germans had to register with the Post Office and carry identification papers at all times. German business owners had to open their account books to authorities. In several states, the attorney general ordered that Germans’ bank accounts be made public.

Several orders appear to have been motivated more by profit than national security. Late in the war, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer seized the assets of German companies in the U.S., which were then sold to Americans. And just days before the war ended, the U.S. confiscated the patent rights of Germans, which included the patents to valuable industrial chemicals and medicines.

The enemy alien laws affected 250,000 German men and 6,300 German women. Out of this number, the Justice Department’s Enemy Alien Registration Section incarcerated 2,048 Germans. Some, like Karl Muck, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, left America when released from camp and refused to ever return.

Those Germans who avoided detention endured harassment and vandalism from Americans throughout the war.

In later years, it became clear that the government’s actions against Germans had been excessive and did little to protect the country from enemy sabotage or subversion. Yet America was destined to repeat the mistake 25 years later with its Japanese citizens during World War II.

The author discusses Great Britain’s solution to the problem with German citizens living in England while it was fighting Germany. Though the U.S. wasn’t yet in the war, he believed German agents were already in America and recommended rigorous methods for isolating both Germans citizens and naturalized citizens from Germany.

Featured image: Photo from Brown Brothers, New York City, from “Alien Enemies” in the March 17, 1917, issue of the Post.

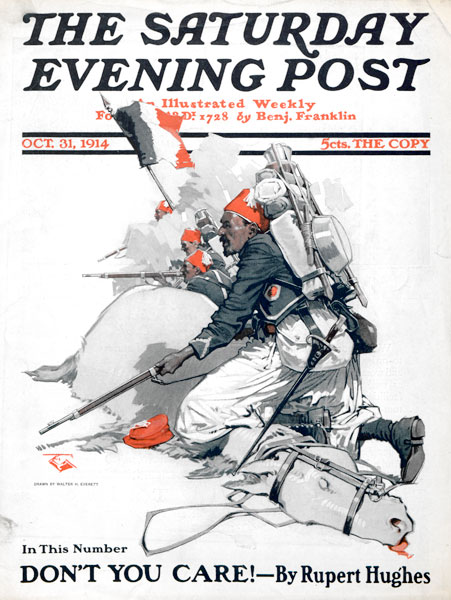

The Great War: October 31, 1914

In the October 31, 1914, issue: The Post publishes its first piece of world war fiction, a war reporter’s shares his experiences in Belgium, and a U.S. senator predicts an economic boom.

The Miller of Ostend

By Melville Davisson Post

In its first piece of World War fiction, the Post brought up a topic that would become one of the major controversies of the war: civilian atrocities.

For weeks, stories about German brutalities against Belgians had been circulating in the media. The stories would become more violent and more numerous as the war settled into a frustrating stalemate. And when the U.S. entered the war, the stories would be revived and embellished to build American support for the war.

Did they actually occur? Did German soldiers really butcher helpless Belgians? What about the story of Germans cutting off the hands of Belgian children?

Were Germans murdered in their sleep or poisoned by the people of Belgium, or ambushed by isolated squads of partisans? In this story, an elderly miller exacts vengeance for a granddaughter killed in a German air attack.

It’s a brutal little story unlike the polite fiction usually run by the Post. But it’s possible the editors chose it out of sympathy for inoffensive Belgium or out of a desire to see Germany punished for violating this neutral country.

Melville Post (no relation) continued to write after the war and, in time, became an early and influential author of mystery stories.

“Presently, far away toward Brussels, a thing like a wingless goose appeared in the sky. It traveled at great speed and soon took form and outline. It came on like a projectile toward Ostend. One could distinguish now its long aluminum cylinder and the strange equipment of the Zeppelin, all painted gray like a warship.

“There was a long, dull roar, and the glass-enclosed terrace of the Kursaal that bowed out toward the promenade of Leopold south along the Digue de Mer flew into a cloud of dust and broken tiles.

“Meanwhile, as though signaled of the approach of the Zeppelin, an English submarine arose like some fabled sea-thing out of the slime of the harbor. A figure emerged from the turret, seized a lever, and a gun that was folded into the back of the monster swung up into place, other figures appeared, and the gun lifting perpendicular opened fire on the dirigible. …

“Finally the Zeppelin, driving dead away toward Brussels, was seen suddenly to list. It hung for a moment half balanced over, then it glided slowly down. A shot traveling parallel with the cylinder had ripped open the gas compartments along the whole side. …

“It did not fall — the gas chambers on the other side of the long aluminum envelope were enough to prevent that, but not enough to hold it in the air, and listing heavily it descended slowly into the fields. The detachment of Belgian cavalry riding the Brussels road raced toward it.

“At the dull boom of the first explosion the old miller, sitting on his door step, arose and started to return to Ostend. … He knew the city, and the direction of the sound located for him where the deadly thing had struck.

“His awful fear was justified. Under the wrecked glass of the Kursaal, among the scattered cots and the wounded—now mangled dead men—a little broken thing, with a red cross stitched to her sleeve and the sun still nestling in her hair, lay motionless across the sill of a door.”

Marsch, Marsch, Marsch, So Geh’n Wir Weiter

(the German translation of the American Civil War song lyric “Tramp, tramp, tramp, the boys are marching”)

By Irvin S. Cobb

Cobb reported he’d seen none of the atrocities that others had reported in Belgium. But in this installment, he sees several examples of the German’s stern military justice.

The German army developed a harsh attitude toward the Belgians. They had originally expected Belgium would permit them to march through the country to invade France. They were surprised, then angered, when the Belgians not only refused German demands to pass through, but resisted their advance with force.

The first stories of atrocities, it seems, came from the Germans, who reported that Belgian civilians were waging a guerilla war, ambushing prisoners and sabotaging equipment. As Cobb reports, German officers believed these stories and used them as justification for executing people they considered dangerous to their army. The colonel who kept him under guard told Cobb he could not cross the front lines to reach Brussels for fear of what his own men might do.

“‘For your own sakes … I dare not let you gentlemen go. Terrible things have happened. Last night a colonel of infantry was murdered while he was asleep; and I have just heard that fifteen of our soldiers had their throats cut, also as they slept. From houses our troops have been fired on, and between here and Brussels there has been much of this guerilla warfare on us. To those who do such things and to those who protect them we show no mercy. We shoot them on the spot and burn their houses to the ground.

“‘We make no attempt to disguise our methods of reprisal. We are willing for the world to know it; and it is

not because I wish to cover up or hide any of our actions from your eyes, and from the eyes of the American people, that I am refusing you passes for your return to Brussels today. But, you see, our men have been terribly excited by these crimes of the Belgian populace, and in their excitement they might make serious mistakes.’

“On the second morning of our enforced stay … we watched a double file of soldiers going through a street. … Two roughly clad natives walked between the lines of bared bayonets. One was an old man who walked proudly with his head erect. The other was bent almost double, and his hands were tied behind his back.

“A few minutes afterward a barred yellow van, under escort, came through the square fronting the railroad station and disappeared behind a mass of low buildings. From that direction we presently heard shots. Soon the van came back, unescorted this time; and behind it came Belgians with Red Cross arm badges, bearing on their shoulders two litters on which were still figures covered with blankets, so that only the stockinged feet showed.

“Along toward five o’clock a goodish string of cars was added to our train, and into these additional cars seven hundred French soldiers, who had been collected at Gembloux, were loaded. With the Frenchmen as they marched under our window went, perhaps, twenty civilian prisoners, including two priests and three or four subdued little men who looked as though they might be civic dignitaries of some small Belgian town. In the squad was one big, broad-shouldered peasant in a blouse, whose arms were roped back at the elbows with a thick cord.

“‘Do you see that man?’ said one of our guards excitedly, and he pointed at the pinioned man. ‘He is a grave robber. He has been digging up dead Germans to rob the bodies. They tell me that, when they caught him, he had in his pockets ten dead men’s fingers which he had cut off with a knife because the flesh was so swollen he could not slip the rings off. He will be shot, that fellow.’

“We looked with a deeper interest then at the man whose arms were bound, but privately we permitted ourselves to be skeptical regarding the details of his alleged ghoulishness. We had begun to discount German stories of Belgian atrocities and Belgian stories of German atrocities. I might add that I am still discounting both varieties. I hear of them daily, almost hourly, but usually the proof is lacking.”

Permanent Prosperity

By Albert J. Beveridge

Not only did former U.S. Indiana Senator Beveridge (R) expect the war would bring an economic boom to the United States, he thought it could last even beyond the war. But it would require the government keeping politics out of its economic policy.

“Every day we hear of the great material prosperity the present world war will bring us. … We are adjured to lament this tragedy of the nations and to pray for its ending, nevertheless we are advised to make the most of the situation and to fill our pockets while we can, and as full as we can.

“Without any foreign war, and purely from our natural advantages, handled in a common-sense manner, we ought to have a much greater prosperity in the United States than we ever have had. … Why, then, is this not the case? … Partisan politics.

“[It] turns the crank, which runs the endless chain of tariff ups and tariff downs; of business fever and business chill; of a diseased prosperity and a diseased depression. Thus it is that tariff earthquakes periodically shake and shatter American business. Thus it is that we have not and never have had steady and normal business conditions. Thus it is that such a thing as permanent prosperity is unknown in America. And steady normal business and permanent prosperity never can be had so long as we allow partisan politicians to make our tariff the football of partisan politics.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.