Reckoning with the #MeToo Movement: An Interview with Linda Hirshman

There was a whisper in one of my online communities. “My former manager is on the job market,” one tech woman wrote. “Since he’s leaving the company due to being put on a PIP (personal improvement plan) for his treatment of women and PoC employees, I thought I’d warn people. Here’s his name.”

For most women, the #MeToo movement wasn’t a surprise — except perhaps that so many famous men finally faced the consequences of their actions. Given the dismal gender ratio in many professional fields, and recent reports about abuses in every business from Hollywood to tech firms, preventing sexual harassment is an urgent matter to women. I’ve met few women without a personal story about sexual harassment or sexism.

We have seen several reasons to cheer at the #MeToo movement, as well as heartbreak when we see how little progress has been made. At best, we’re in a time of transition, where previously-accepted behavior now results in someone losing his job.

As is true during any time of change, it’s important to understand where we started, how we got here, and how the past should inform our path forward.

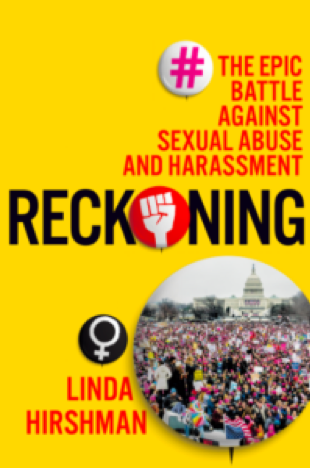

That’s why I so urgently wanted to sit down with Linda Hirshman. Her book, Reckoning: The Epic Battle Against Sexual Abuse and Harassment, lays out the important events in the pursuit of justice for workplace harassment, explains its unresolved legal issues, and compares it to earlier social changes. It’s not just that Hirshman is an experienced lawyer who has argued in front of the Supreme Court, or that she’s a marvelous writer (the sort who makes you stay up past your bedtime to read “just one more chapter”). I wanted Hirshman’s wisdom personally because I learned so much from her earlier book, Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution, which chronicles the social history of the LGBTQ movement.

(For transparency: I know Hirshman, though not exceptionally well. She’s a member of my book club, and, it turns out, the exact right person to explain Oscar Wilde’s legal problems in the context of The Picture of Dorian Gray.)

I wanted to find out how the #MeToo movement compared to similar movements to advance human rights; what moved it from the theoretical to the practical? How far away are we from genuine societal change?

As Hirshman writes in Reckoning, “In any social justice movement in America — abolition, racial civil rights, feminism, gay rights — the battle always seems to involve the same three campaigns, although not always in the same order. First, the movement must appeal to the judiciary and the rule of law, so central to American Democracy. Yet the court does ultimately follow the election returns, so the second field of battle is popular politics. Finally, to achieve the first two goals of legal and political change, a movement must, at day’s end, win the air war and change the culture.”

The nature of the cultural part of social change depends on the time and place. “The piece that interested me is the media,” Hirshman says. In the gay revolution, the theater was a key influence. In #MeToo, it’s been the Internet and print media. (You can read a book excerpt from Hishman’s Reckoning, about the feminist Internet, The Revolution will be posted.)

One frequent element of real social change is a backlash, Hirshman explains, once you get close to the tipping point. “You get this weird social change,” she says, as the established culture responds with a pendulum swing to the old ways of doing things. She has a whole chapter about how the establishment culture responded to feminism, and what it took for it to revive.

These events look like a setback, Hirshman says. “But under the surface, social change is accepted. You get a little more of what you need.” The backlash has unpredictable consequences, such as the Clarence Thomas hearings (where Anita Hill’s testimony of sexual harassment was rejected) that led to more women going into office, in what became known as the “Year of the Woman.”

Some men become paranoid in the wake of the movement, scared to interact with women lest they be accused of impropriety. For example, 60% of male managers now say they’re uncomfortable mentoring women. Doesn’t that get in the way of women moving forward?

Hogwash, Hirshman says. Men were already refusing to mentor women, or to fund women in venture capital.

“This is male hysteria,” she says. “It’s punitive. There is no universe in which going to coffee with someone will be mistaken for romantic behavior. Men threatening to stop [meeting with women professionally] are blackmailing uppity women. To say nothing of being illegal according to the civil rights act of 1964.”

There’s nothing wrong with a professional relationship, she points out. But don’t try to date someone when you are in a business relationship, where you can possibly have a career impact on the other person.

“The social power is so heavily in favor of the men that they just shouldn’t [look for a romance at work]. If that means less courtship, so be it.”

Hirshman would like us to keep in mind that social change always happens when there is a crack in the establishment. “The arc of history does not bend towards justice; it more wiggles like a politician who discovers his cell phone has been hacked,” Hirshman says.

Featured image: The Women’s March in San Francisco, January 20, 2018. (Sundry Photography / Shutterstock.com)