The Middle Eastern Prince Who Tried to Change the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles, the document that ended World War I, turns 100 years old on June 28. The Treaty is known for making Germany accountable for the losses of the war and for redrawing many national borders in Europe.

What is less well known about the Treaty is how one Prince from the Hejaz kingdom attended the Paris Peace Conference to try and reshape the Middle East.

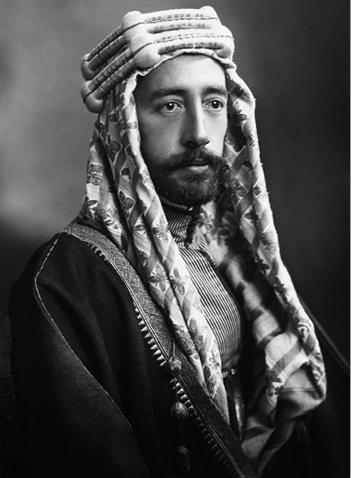

At the outset of the war British captain T.E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia) journeyed to the Middle East. He was seeking a ruler to lead the stalled Arab rebellion against the Ottoman Empire, with whom the British Empire was currently at war. The British wanted to weaken the Ottomans, and the Arabs resented being under their rule, so the task seemed straightforward. Lawrence found Emir (Prince) Feisal, the third son of the King of the Hejaz kingdom (modern-day Saudi Arabia) and knew he had found his leader. A charismatic man, Feisal was also believed to be a direct descendent of the prophet Mohammed, further encouraging the support of his followers. With the Emir in charge and the British supplying aid, the rebellion began in 1916. Arab troops reached the city of Damascus two years later.

This rebellion aided the British cause during the war, but as soon as the fighting stopped Arab leaders found themselves at odds with their former allies. In 1916, British and French diplomats had collaborated to divide the lands of the Ottoman Empire between their two nations. Known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, these nations split the Arab region into zones of European influence. This agreement went against the promise of independence the Arab army had begun a rebellion to achieve.

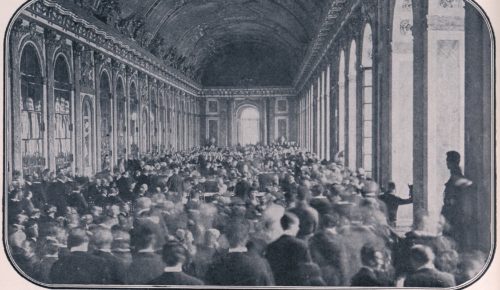

At the end of the war Lawrence found himself called to Paris to participate in the Peace conference that would redefine the world after the war. Representatives from around the world gathered to create what would later be described in the June 26, 1922, issue of The Saturday Evening Post as “that recipe for ruin otherwise known as the Versailles Treaty.” Knowing that few politicians were concerned about the Middle East after the devastation in Europe, Lawrence encouraged Feisal to come with him and argue for Arab independence.

He did just that, though not without French resistance. Arab independence undermined French desires for control the Middle East, and the French delegation made several attempts to keep Faisal from the conference. Refusing to admit him as a British Delegate (the title Feisal had arrived under), the British government was forced to issue formal complaints. The British intervention allowed him entry, though only as a representative of the Hejaz region. Both Lawrence (who felt guilty for encouraging the rebellion with promises of independence) and Feisal worked hard to convince delegates that Arab independence was something worth fighting for.

Finally, Feisal stood before representatives from the British Empire, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States (including President Wilson) and argued (with Lawrence translating) that the Arab army had fought for the promise of independence after the war. Twenty thousand soldiers had lost their lives in a rebellion for a promise of freedom that was undermined by the Sykes-Picot agreement. When asked if Feisal meant to rule over one massive Arab nation, the Emir asserted that he did not mean to speak for the desires of all Arab peoples, he only aimed to give them the right to choose for themselves. The French, however, continued their attempted sabotage, bringing in their own Syrian representatives to degrade the Emir in front of the delegates.

At the end of the conference, delegates chose to honor the Sykes-Picot agreement over Feisal’s and Lawrence’s opposition. Europeans divided the Middle East into nations in a manner described by a February 11, 1922 Post article, titled Business Revival and Foreign Trade, as having “disturbed the currents of traffic which go back to the time of the children of Israel in Egypt, to the early days of Bagdad and Damascus, and to Marco Polo.” The French and British selected governments for the countries they had formed without consulting the governed, increasing tensions in those nations that later lead to violent coups and wars that are still fought today.

Emir Feisal was made king of British-controlled Iraq as consolation. Initially reluctant, the Emir agreed to rule (crowned in a ceremony with the British anthem “God Save the King” playing) and spent his time as King forming the national Identity of Iraq. He continued to advocate for pan-Arab nationalism until his mysterious death at age 48 in 1933. Feisal had been staying in Bern, Switzerland when he was found dead in his hotel room. The official cause of death was a heart attack, though an autopsy was never performed, and the King showed some signs of arsenic poisoning. Arab national sentiment led to the first of a series of violent coups 25 years later.

The Paris delegates’ actions at the Paris Peace Conference had far reaching consequences, though not many people connect the roots of Middle Eastern conflict to those men in Paris in 1919.

Featured Image: Faisal’s delegation at the Paris Peace Conference. (Wikimedia Commons)

Strangling Instead of Shooting: Waging War by Embargo

If you’re old enough to remember 1973, you might recall those long lines of cars that began forming at gas stations that fall.

These lines were the result of the oil embargo — 44 years ago this month — against the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and the Netherlands, imposed by the Middle East nations of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Nations (OPEC), who were angered by the Western nations’ support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War.

So in October 1973, OPEC cut oil production by 25 percent and reduced their exports to NATO members in Europe. They cut off all oil exports to the U.S. The embargo would be lifted, they said, when Western nations pressured Israel to return land it had captured during the war and a process to restore peace in the Middle East had begun.

The embargo’s effects were immediate. Oil rose to $5.11 a barrel, an increase of 70 percent. By the following June, it reached nearly $12 a barrel.

America still produced most of its own oil, but even the 15 percent loss of its Middle East fuel was felt across the country. Pump prices rose from 38.5¢ to 55.1¢ a gallon. The drop in supply meant gas stations frequently ran out of fuel, leading to long lines of cars and their panicked drivers.

Although OPEC dropped the embargo in April 1974, after President Nixon pressured Israel to withdraw from some of its conquered territory, Americans realized firsthand what a powerful tool embargoes could be. In 1975, The Saturday Evening Post suggested in “Our Option of Economic Warfare” how the U.S. could apply its own economic leverage to resolve international issues.

The idea was tried out when America placed a grain embargo on the Soviet Union in response to its 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. Unfortunately, the U.S. was then acting alone. Russia readily obtained the grain it needed from other countries, while American farmers suffered a drop in prices.

The U.S. was more successful with later embargoes. By limiting exports, restricting business and economic aid, or freezing assets, it has pressed reforms on countries that sponsor terrorism, violate human rights, or develop nuclear weapons.

These economic pressures led to Iran agreeing to curtail its nuclear weapon program. They have also created hardships for North Korea, though at this date, it’s uncertain that embargoes will successfully yield change.

American Angel

Frequent moves and fast-forming friendships are hallmarks of the military lifestyle. So is a deeply rooted sense of mission and loyalty to country and the men and women who serve. That mission may be what drives Karen, 51, to commit extraordinary acts of charity through her nonprofit organization, Landstuhl Hospital Care Project.

Since 2004, the organization has shipped more than 200,000 pounds of donated clothing and supplies, often at Karen’s own expense, to wounded and ailing soldiers in the Middle East. The bulk of donated items are mailed to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, the largest American military hospital outside of the U.S. Karen also sends supplies to medics, nurses, and chaplains at more than 150 military units throughout Afghanistan, Iraq, and other Middle East countries with U.S. military operations. “If we can help just one military member with a gift, then I hope they feel the respect, gratitude, and the love we have for them. That’s what keeps pushing me on—knowing that it makes their future a little bit easier,” Karen says.

Her labor of love can be back-breaking at times. Working out of her home in Stafford, Virginia, she fills boxes with an assortment of requested items. A typical shipment might include sweatpants, Crocs, socks, towels, pillows, or blankets. Four or five days a week, she drives to the post office in her white Chevy Suburban, which she reluctantly purchased a few years back when the charity grew too large for her beloved Jeep to handle.

Sometimes, Karen is lucky enough to find volunteers to help. But often, it’s just Karen and her packing tape filling up boxes and taping them shut for their distant journey. Halfway through 2012, Karen had already shipped 946 boxes, a number on pace to beat last year’s tally of 1,713 boxes. In fact, supply and demand have grown rapidly since the charity’s first year when it sent its first 33 boxes of supplies. Karen expects demand will increase as other nonprofits close their doors or shift their focus to helping returning soldiers.

The organization grew out of a simple request from Karen’s daughter who was living in Germany, where her husband was stationed. Would she collect DVD and videotape movies and send them to wounded soldiers at nearby Landstuhl hospital?

Karen appealed to her circle of family and friends, collecting 485 movies. Grateful for her enthusiasm, the chaplain at Landstuhl asked Karen to collect sweatpants. Again, she turned to family and friends who donated 108 pairs. To her dismay, she learned the number was a “drop in the bucket” to meet the hospital’s needs. At the time, as many as 1,000 soldiers were arriving at the hospital every month, and their first stop was the Chaplain’s Closet, a place where soldiers received donated clothing and supplies to replace their tattered and bloody clothing.

Karen reached out to veterans groups such as the American Legion and soon, donations came pouring in. But the more supplies she mailed to Landstuhl, the greater the requests for donations. In just a year, word-of-mouth spread among military medics and medical staff in the Middle East about the woman in Stafford, Virginia, who almost never said “no” to a request for supplies.

“There was never a plan for me to start a nonprofit,” Karen says. “What started as one or two boxes turned into thousands.”

Karen knew she needed help with the legal and financial realities of running a charitable organization. Today, a small but loyal group of volunteers—many with strong military ties—handle accounting, communications, and other vital support services.

In addition to running her nonprofit, Karen also spends a month at Landstuhl hospital every year as a volunteer, handing out clothing and supplies from the Chaplain’s Closet.

It was at the hospital that she met Marine Lance Corporal Justin Reynolds. In 2006, the young Marine was recovering from shrapnel wounds and other injuries suffered when his Humvee hit an Improvised Explosive Device in Iraq.

From the start, the wounded soldier from Ohio clicked with Karen and gave her the nickname “Mom Two.” One day, Karen got a call from Ann Reynolds, Justin’s mother. The soldier had returned home to recuperate but suffered a stroke resulting in partial paralysis. Karen hopped in her car and drove to the hospital in North Carolina where Justin was fighting for his life. There, the two “moms” met face-to-face for the first time.

Nearly two years later, a second setback robbed Justin of his speech and motor coordination. Again Karen dropped everything to visit the Marine and his family, now in nearby Richmond, Virginia. “Karen has been such a great friend,” says Ann Reynolds. “If I need something, I call Karen. She knows how to get it.”

Karen’s devotion to Justin and his family is a clear example of why she works so tirelessly for wounded military members. Karen, her friends and family members say, is the kind of person who simply refuses to back down. Karen believes Justin one day will regain his speech and motor skills. Until that day, she will support him, just as she supports her charity—until every military member comes home.