The 1969 Draft Lottery Didn’t Solve Nixon’s Problems

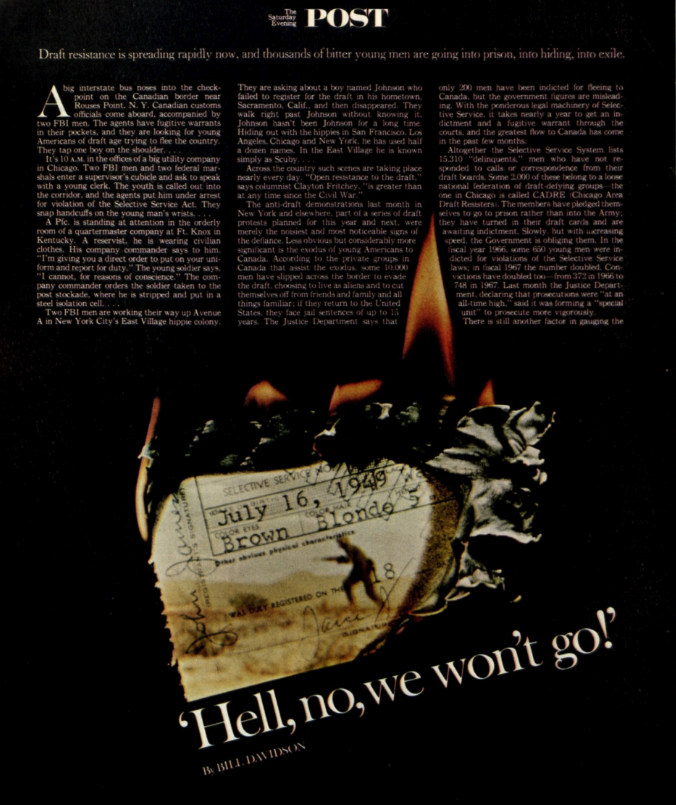

At the height of the Vietnam War, perhaps no stateside military issue caused as much friction as the draft. There was certainly already a groundswell of antiwar sentiment. The Saturday Evening Post ran an article on draft resistance called “Hell, No, We Won’t Go!” in the January 27, 1968 issue; the cover even depicted a burning draft card. The dislike for the random nature of the draft would only get worse in the days before and after the December 1, 1969, draft lottery drawing, which happened 50 years ago this week.

The draft had already been cited as an unfair process, and many Americans weren’t happy with the ongoing escalation of the country’s involvement in the war. With troop levels jumping from 82,000 in-country in 1965 to 500,000 by 1967, there didn’t seem to be much of an end in sight. Other social movements, like the hippie counterculture and the Civil Rights movement, began to intersect with anti-war activism, prompting louder and louder calls to end the U.S.’s role in the conflict.

President Richard Nixon sat in the center of it all. When he took office in January of 1969, he had publicly expressed a desire to begin a drawdown in troop levels. However, he wanted to achieve some kind of solution that brought Americans home, ensure the security of South Vietnam, avoid the appearance of a U.S. “loss” in any way, and move the U.S. military to a volunteer force; it was basically an impossible task. On November 26, 1969, Congress moved to modify part of the Military Selective Service Act of 1967; that adjustment gave the president the authority to change how the draft worked. That same day, Nixon issued Executive Order 11497, which allowed for random selection, or a draft lottery. It was held on December 1, 1969.

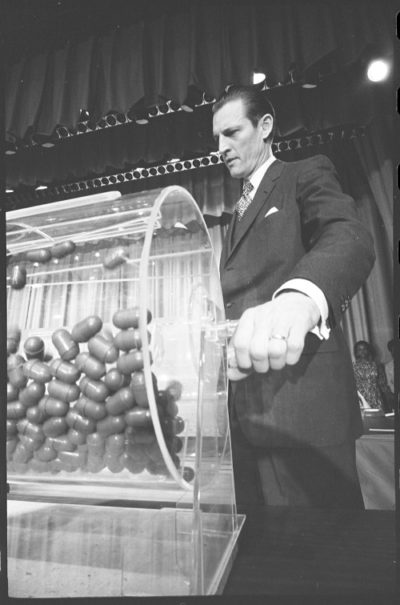

The lottery worked by putting every day of the year (including February 29) onto individual slips of paper and then packing each paper into a plastic capsule. The capsules were mixed in a shoebox, poured into a jar, and then drawn one at a time. The first drawn number was 258, which corresponded to September 14, the 258th day of the year. That meant that all eligible men of draft age (that were born on September 14 during a span of years that ran from January 1, 1944 to December 31, 1950) would be called to serve at the same time. Deferments were available for draftees that were actively in college or deemed physically unable to serve; some registered for the National Guard in an effort to stay home and avoid active deployment overseas.

The Draft Lottery. (Uploaded to YouTube by AP Archive)

At the time of the draft, 850,000 young Americans were affected. Local draft boards, with a span of 18- to 26-year-olds in the eligible range, chose 19-year-olds first., altering an earlier rule in which the oldest end of the pool was chosen first. The lottery, which some took to be a fair, random way of selecting personnel, turned out to have all sorts of incongruities and problems, with some dates having a higher concentration of births and perceived inequities in selection at the local draft board level, since wealthier draftees were more likely to earn a deferment due to college enrollment. It actually exacerbated opposition to the war, according to books like Peace: A History of Movement and Ideas by David Cortright; Cortright wrote that Nixon’s own task force for exploring the volunteer army transition reported that draft resistance surged “at an alarming rate” in 1970.

As the war went on, Nixon juggled drawing down forces while trying to negotiate an end to hostilities. Drafts occurred in 1970, 1971, and 1972; they were set to expire in 1973 under the original provision of the order, but the January 1973 cease-fire agreement negated it entirely before the last draft would have happened. While 18-year-olds are still required to register for Selective Service, the military did segue to a volunteer force after the close of the Vietnam War.

Featured image: The Drafty Lottery of 1969. (Photo by Warren K. Leffler; LOC.gov)