The Buried History of West Virginia’s Coal Wars

Unlike most holiday imagery, a symbol for Labor Day can be difficult for many Americans to conjure. Is it a muscled arm wielding a tool? An American flag? The dreaded hammer and sickle?

To West Virginians like Wilma Steele, the perfect symbol for Labor Day is a red paisley bandanna. This was, after all, the unifying costume of West Virginia coal miners during the largest labor uprising in American history.

Steele is a board member and co-founder of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, a humble collection of artifacts and displays in Matewan, West Virginia. The museum is one of the only surviving testaments to the struggles of the state’s coal miners in the early 20th century – a labor story that Wilma believes more people ought to know.

Matewan sits in Hatfield-McCoy country, in the southwest corner of the state, just across the Tug Fork River from Kentucky. The town of 500 people includes a downtown district designated a National Historic Landmark for its role in the escalation of the mine wars.

At the turn of the 20th century, southern West Virginian coal miners faced uniquely squalid working circumstances. While the United Mine Workers of America had organized many of the mines in Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, mine owners in West Virginia discouraged their workers from unionizing, hiring guards from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to squash dissent and evict striking miners. West Virginian mine workers lived in company housing and bought their groceries (and mining tools) from company stores with their pay, a company currency called scrip.

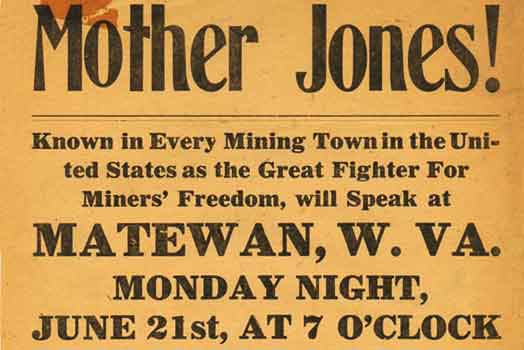

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, a brassy and bold labor leader, began speaking to miners around the state in the 1890s, giving powerful calls to action laced with obscenities. According to James Green’s The Devil Is Here in These Hills, a U.S. district attorney “named her ‘the most dangerous woman in America’ because she could, by her own words and deeds, persuade hundreds of men to walk out the mines.”

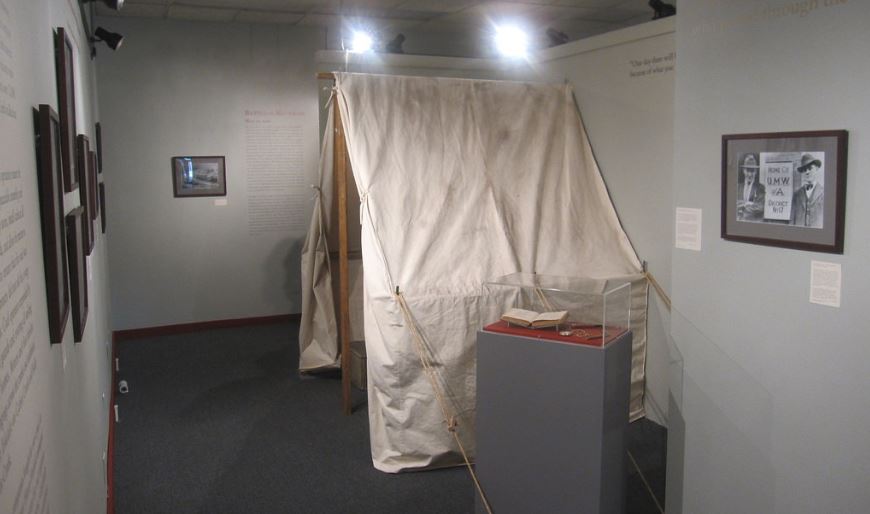

And she did. The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strikes brought a year and a half of armed conflict between miners and mine guards to the Kanawha Valley southeast of Charleston in 1912. After striking for better wages, an eight-hour workday, and the right to assemble and organize – all having been afforded to their northern counterparts – miners were evicted from their houses and took to canvas tents in the hills provided by the UMWA. Mother Jones called on the workers to take up arms against the Baldwin-Felts agents, who had shot at the miners’ tents from train cars, and the workers retaliated. Miners fired on trains bringing in mine guards and strikebreakers and blew up railways with dynamite. Governor William Glasscock declared martial law and sent the National Guard to bring order to the region three times, and his successor Henry Hatfield finally established a lasting – albeit all-around unsatisfying – negotiation between mine owners and strikers.

The West Virginia mines saw relative peace during World War I, but the next eruption of violence put little Matewan on the map in 1920. After a significant rise in UMWA membership in Matewan, Baldwin-Felts agents arrived to oust union members from Stone Mountain Coal Company housing. The town mayor, Cabell Testerman, and union-sympathizing police chief, Sid Hatfield, confronted the agents near Matewan’s train station on their way out, and the ensuing shootout left 10 dead: seven agents, two miners, and mayor Testerman. No one could agree on who shot first, but the Matewan Massacre rallied UMWA members in West Virginia to boost their southern membership and begin a general strike.

Martial law was declared in Mingo County, and scores of miners were arrested under suspicion of union activity. The governor sent over 1,000 special police to Mingo, strengthening UMWA claims around the state that the county’s miners were under attack.

Meanwhile, Sid Hatfield was acquitted in the murder trial and became a hometown hero to Mingo County miners. But when Hatfield and his deputy were gunned down by Baldwin-Felts agents on August 1, 1921, the already-volatile strike became an all-out war.

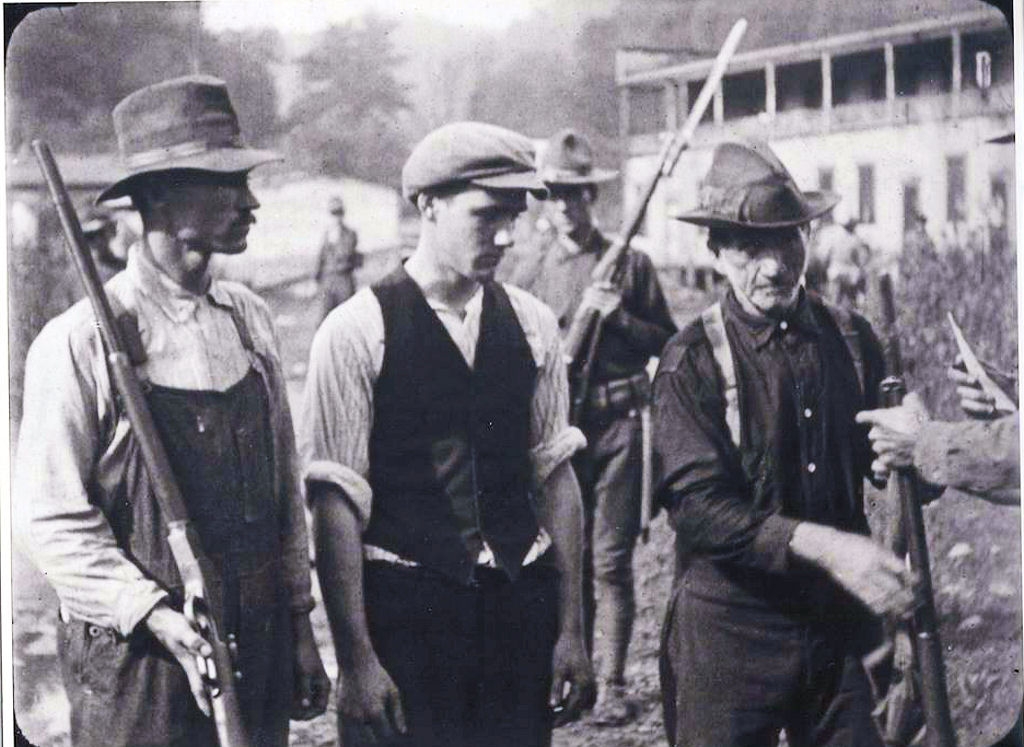

“The only way to get your rights is with a high-powered rifle,” claimed organizer and longtime miner Frank Keeney, as he gathered thousands of miners in Lens Creek in the weeks following Hatfield’s assassination. The “Redneck Army” consisted of immigrants, black miners, and generational West Virginians wearing red bandannas around their necks. The plan was to march to Mingo County to free their jailed comrades, but first the army would have to cross Logan County, where Sheriff Don Chafin had assembled the Logan Defenders, made up of thousands of local and state police as well as Baldwin-Felts agents.

The 10,000-strong Redneck Army clashed with the Logan Defenders at Blair Mountain. Chafin’s men utilized machine guns and even biplanes with homemade bombs against the miners in the five-day skirmish. Even so, only about 20 men died overall in the Battle of Blair Mountain. Two thousand federal troops broke up the fighting and dispersed the respective forces under the command of President Harding.

The leaders behind the Redneck Army, Keeney and others, were indicted for state treason, but most escaped conviction. The harshest blow was to the UMWA, whose numbers dwindled in the coming decade. It wasn’t until F.D.R.’s New Deal programs of the 1930s that the miner’s union picked up again.

The stories of Mother Jones, Frank Keeney, Sid Hatfield, and the rest of those involved in the mine wars were kept among West Virginians for generations – along with the physical remnants of the state’s difficult past.

Long before they opened the Virginia Mine Wars Museum in 2015, Wilma Steele teamed up with some other West Virginians to incorporate their heirlooms, artifacts, and local history in a way that could benefit everyone. A canary cage used by miners during the period kept the birds that would warn the workers of dangerous methane in the mines. Oil-wick cap lamps kept an open flame on a wick attached to the workers’ hats that both allowed them to see their work and also posed the severe risk of igniting explosions. Metal scrip pieces could buy provisions at the company store while only going for about 75 percent of their worth for cash. Rusted remnants of an 1873 Remington carbine and some bullet casings recovered from Blair Mountain illustrate well the tools of a miner who has put down his pickaxe.

Kimberly McCoy, a museum guide who grew up in Matewan, shows guests the bulletholes on the back of the museum’s brick building from the Matewan Massacre while explaining how folks in town always felt about “Smilin” Sid Hatfield. “Children around here are generational coal-mining children. They need to know how their grandparents and great-grandparents struggled for them to be able to choose a profession today instead of going into the coal mines at 15 years old,” she says.

The museum believes the story of the mine wars should be taught to all West Virginian schoolchildren. That’s why, this year, they’ve created curricula for fourth-, fifth-, eighth-, and eleventh-grade students to learn about the decades-long struggle of the state’s miners. Given the complicated and contradicting historical accounts of the events, students are encouraged to read primary sources and think critically about the working conditions of miners and child laborers and to take part in role-play, considering how they would’ve acted 100 years ago.

Keeping the history of the mine wars alive for West Virginians has been a battle of its own. In 2011, Wilma Steele marched on Blair Mountain with hundreds of others in the group Appalachia Rising to call for an end to mountaintop removal mining and declare the mountain a protected historic site. The place where 10,000 “rednecks” took up arms against big coal was, coincidentally, at risk of being mined itself by several companies who claimed surface mining permits on Blair Mountain.

Mountaintop removal mining began in the 1960s, but it became more prevalent in Appalachia in the ’90s. The widely-criticized form of coal mining is executed by blasting off mountaintops with explosives to reach coal seams underneath. According to the EPA, mountaintop mining poses significant risks of contaminating nearby streams and rivers. Many Appalachians, like Steele, have long opposed the practice because of the detriment on nearby communities: deforestation, loud explosions, and dust accompany the mountaintop mining process. The landscape is often spoiled, and the number of jobs created in the region cannot begin to reconcile with the damage.

Blair Mountain Battlefield was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, then de-listed after a few months due to objections from the coal companies with permits in the area. Just this June, the site was added back to the list after years of legal battles and advocacy from groups like The Sierra Club and Friends of Blair Mountain.

The spirit of the Redneck Army was also present in the state this past February when West Virginia public school teachers protested in Charleston during a nine-day strike for higher wages while wearing red shirts and – for some – red bandannas. The demonstration set off a chain of teacher strikes and marches in Oklahoma, Arizona, and Kentucky.

Wilma Steele believes in the historical significance of the red bandanna, and that’s why she shares them with activists everywhere she goes. “The paisley pattern on a bandanna shows organic designs and geometric designs in balance,” she says, “the figures in paisley could look like a tear, or a drop of blood, or they could come together to form a heart.” Her husband Terry was a 4th-generation coal miner, and he belongs to UMWA 1440 in Matewan. The building housing the union presides over the historic town, and it’s a short walk from where Sid Hatfield confronted agents from Baldwin-Felts. Kimberly McCoy comes from generations of miners too. The historic labor struggles of West Virginians might be difficult for outsiders to grasp, but – like the bulletholes in the brick of the museum’s exterior – the implications of the mine wars are imprinted on the people. “I know the history,” McCoy says, “it’s my history.” When asked what the stories of Sit Hatfield and Frank Keeney can mean for others, she says, “We are the story of the working class. We’re proud of rednecks here.”

Sources and further reading:

The Devil Is Here in These Hills by James Green

Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922 by David Corbin