North Country Girl: Chapter 65 — “You’re Fired”

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Through persistence, a lost diamond bracelet, and my best good fairy gift, my incredible luck, I was a real live magazine editor (well, assistant editor), at Viva, a magazine that suffered from multiple-personality syndrome and was losing boatloads of money every month.

The fact that Viva was such as mishmash of a magazine was not due to an incompetent staff. Everyone did their job well; we just had completely different ideas of what that job was.

I thought my job was to get as much free stuff as possible, through mentions in my frivolous little section, “Tattler,” volunteering to model products myself. I was photographed posing in a racing jacket that in real life made me look as if I were swaddled in Reynolds Wrap and running a device over my face that promised smoother skin, and was as effective as a wood sander in removing my epidermis.

The one thing I did take seriously was my responsibility to my first friend at Viva, the down-trodden managing editor, Debby, who was tasked with getting the magazine to the printers. I made sure that my copy had left my typewriter and was at the art department well before it was due.

The person who did the best job was Viva’s extraordinarily talented art director, Rowan Johnson. Through a fog of drink and drugs, and always past deadline, Rowan created stunningly beautiful covers for Viva. Unfortunately, at newsstands in most parts of the country Viva was still thought of as the penis magazine. Rowan’s ground-breaking work was doomed to be wrapped in brown paper and stuck under the counter with Hustler and Club magazines.

Most of the Viva editorial staff regarded their job as ignoring the penises of the past and the still-present soft porn and erotica and transform Viva into a competitor of Ms. and Mother Jones. Between the fashion sections featuring $1,000 dresses and the photos of nude smooching couples were articles such as “Daughters of the Earth: The Difficult Lives of Indian Women,” “Jane Fonda: An American Revolutionary,” “A Guide to Abortion in America,” and “The Facts about Wife Abuse.”

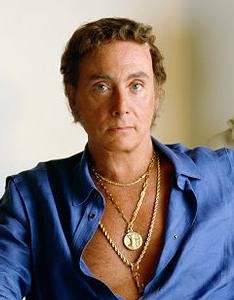

What Bob Guccione, who was footing the bill for this cockamamie magazine, thought of Viva was irrelevant, until suddenly it wasn’t. Guccione happened to pick up an issue of Viva whose lead story was a 5,000-word profile of La Pasionaria, a woman who had fought against Franco during the Spanish Civil War and was now an infamous Basque separatist.

Bob had taken one look at the wrinkle-faced, white-haired La Pasionaria, photographed in the style of Margaret Bourke-White, and yelled “What the f— is this?” Even if they were brave enough to attempt it, no one around him could have explained to Bob why there was a full-page photo of an 83-year-old Communist wrapped in a black serape in a magazine aimed at young, sexy, fashion-forward sophisticates.

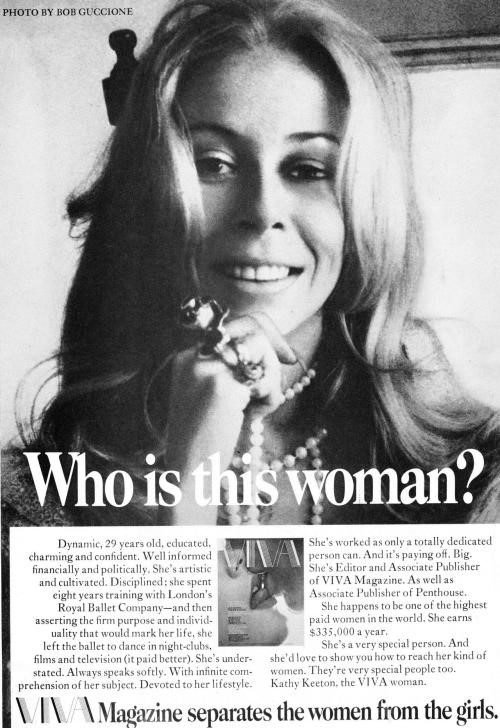

The era of the leftist, feminist attitude of Viva was over. Kathy decided that what Viva needed was an editor who could claw it out of the red, someone to woo advertisers into a magazine that now had a reputation for being not only X-rated but radically left-wing.

Our new editor was Helen Irwin, whose previous job was selling ad space in Tennis magazine. She looked the part — of a tennis player, not an editor. She was Amazonian, tall, blonde, sinewy, tan — I don’t think anyone would have been surprised if she had bounded into the office wearing tennis whites. Helen’s job at Tennis must have been easy: the magazine ran articles on tennis rackets and she sold ads to companies that made tennis rackets.

Helen’s mission was to turn Viva into a “consumer” magazine; at her first editorial meeting she said, “I want more beauty features. That will bring in Revlon and Clairol. Get someone to write an article on setting up a home bar. Check with the ad department to see what liquor companies to mention. And we’re going to do a guide to sports equipment. I have a meeting with Wilson this week.”

Viva had a new imaginary reader: A Babe Didrikson with a fondness for cosmetics, booze, and designer clothes, who was also an adventurous sexual libertine (the last item being the infallible Viva gospel according to Miss Keeton).

Several editors defected after this meeting. My scruples allowed me to stay. I liked my job. I liked getting free stuff and dining out on someone else’s dime. Just that week I had eaten blini and caviar at The Russian Tea Room, washed down with a disgusting shot of newly introduced, vile, and short-lived USA, America’s First Potato Vodka; and I had been invited to a Pernod-sponsored dinner at the swanky French restaurant, Le Perigord, on Park Avenue, where every course, from appetizers to dessert, tasted like Good & Plentys.

Of the surviving Viva editorial staff, I was the first to work with Helen, as I always delivered my copy to the art department well before deadline. Usually my bits of fluff were relegated to the assistant art director, but I was nervous about working with Big Blonde; I had begged Rowan, Viva’s genius art director, to do the layout for my “Tattler” section and to let me review it early in the day, before the bar across the street opened.

Rowan phoned me. “Come take a look, Gay.” I hurried down to the art department, made complimentary noises about Rowan’s work, and promised to never ask him again. I had just finished initialling my “GH-OK” on each page when Helen strode into the art department, swinging an imaginary racket. Rowan cowered as she approached; Helen had a good five inches and thirty pounds on him. With a powerful fronthand Helen slapped Rowan on the back and bellowed, “How you doing there, guy?” almost knocking him into the light table.

Rowan did not respond to Helen’s hearty hail fellow well met; he lit a fresh cigarette from the half-smoked one in his mouth and retreated to his office to find something to recuperate with. I handed Helen my pages of the magazine so she could approve my “Tattler” section and Rowan could get back to serious substance abuse.

Helen flipped slowly through the layouts. She started out obviously upset, and as she went on her eyebrows got higher and her jaw tighter. Helen put the papers down, whirled at me, and said, “You must be the most incompetent person I have ever met.”

I was busted. The editor had no clothes. This sport/sales woman had discovered that I was a fraud. It was like a bad dream, hearing someone vocalize my deepest fear, that I was an imposter, with no claim to being any kind of editor or writer or even a decent secretary. After all, I was only hired in the first place because someone wanted to go to bed with me.

I was so incompetent that when Helen asked me, in the chastising tone of a third grade teacher, “Do you know what you have done?” I didn’t have a clue.

Helen shook the pages at me. “Look again.”

I did and I was still baffled. Helen gave me the glare my mother used to when I claimed I didn’t know how to dry dishes. Helen grabbed the layout from me and started reading aloud. What came out was complete goobledegook:

“Loren ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In sit amet imperdiet turpis, a molestie elit. This is what you just okayed to run in the magazine,” she scolded.

The oboli dropped. Art directors, back in the pre-computer era, used what was known as Greek type, though it was actually Latin, as place holders for real copy. Greek type came in sheets so it could be cut up, laid out, rejected, re-cut, re-laid out, and eventually pasted down. Once the layout was approved, the actual text replaced the Greek type, the editor cutting or adding words to make it fit.

My brain was still cross-wired with panic, self-recrimination, and guilt and could not stop my mouth from blurting out “Are you stupid?” I may have added the f-word.

I had been working with Greek type since I picked up my first girl set at Oui, but the new editor of Viva didn’t even know what it was? Rowan, yanked from his office sanctuary and opium den, sobered up enough to explain Greek type to Helen. I stomped back to my cubicle, rolling my eyes all the way.

The next day Helen called me into her office.

“You do not fit in with my plans for Viva,” she said and held out a check.

I was convinced that Helen could not possibly be speaking to me but to someone else who had snuck in behind me; I almost looked over my shoulder. Why was I here with this person who was being fired? The check Helen was waving in her hand had nothing to do with me.

Helen had completely flummoxed me twice in two days. But this time my brain synced up to my mouth. I said, “You’re firing me? You can’t fire me.”

I left Helen and went straight to Miss Keeton, who saw my crazed state, pushed me into her office, and shut the door. There was nothing to be done but to tell the truth, and I knew Rowan would back me up.

“I should not have said what I did, Miss Keeton. I love my job and want to be part of the new Viva.” Whatever that turned out to be. “I don’t deserve to be fired.”

I probably did deserve to be fired, but Helen Irwin, basking in her new position of power, had not bothered to let Kathy Keeton know that she was making a staff change. Her mistake trumped mine.

Miss Keeton sighed and said, “I’ll see what I can do, Gay.” I was dismissed and spent the rest of the day drinking alone at P.J. Clarke’s. I did not want to go home to my struggling artist boyfriend, Michael, and have to explain what I was doing at our apartment in the middle of the day or where next month’s rent was coming from.

I received my third and final wish from the magic diamond bracelet: to get a byline in the magazine, to be transformed from secretary to editor, and now, to keep my job.

Helen could fire me from Viva, but thanks to Miss Keeton, not from the company. As there was no way Helen was going to have someone on her staff who had publicly cursed her out, I was dispatched by Kathy over to Penthouse as editorial assistant, a demotion in title but a promotion from a rapidly failing magazine (Viva would close within the year) to one that made millions of dollars every month, the best-selling men’s magazine in America.

I gathered up my things and moved across the office. Two flimsy grey fabric-covered boards were erected for me in the back of a big room where three secretaries sat. Tucked away out of sight, I felt as if I had been smuggled into the Penthouse editorial department.

North Country Girl: Chapter 64 — The Accidental Editor

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

The Cape Cod vacation of drinking, solo hiking, and free fish was over; I was back at work. I fretted over my imprisonment in my secretarial fishbowl and tried to figure out a way to escape to the editorial side of Viva. The insanity of my chocolate article — an article both the advertising saleswomen and the editorial staff hated, an article about candy only one percent of the world could afford, an article written by a secretary — was a Hershey’s miniature of the insanity that Viva was at the time, a mashup of Vogue, Playgirl, and Ms.

The imaginary reader of Viva was a young woman with an unlimited budget for clothes and makeup (not to mention chocolates), who enjoyed sex with a wide variety of partners and without a shred of guilt, with literary taste that ran to Alice Munro and Joyce Carol Oats and who was a card-carrying leftie. I’d love to meet that girl. She’d be my new best friend.

The editors were on a mission to put Viva on the side of the angels, feminist angels anyway, with serious articles about the Equal Rights Amendment, sexism around the world, and profiles of firebrand women’s libbers.

This antidote to Viva’s penis problem (an experiment with the full Monty that did not end soon enough) was like grabbing the wheel of a car headed off a cliff and yanking it as far to the other side as possible, no matter what was there. Their concept of the Viva reader was the female equivalent of the man who supposedly bought Playboy for the articles, a reader so enthralled with the feminist content that she could ignore the gauzy photos of entwined lovers caught in the act, the ads for Penthouse, and the tips on how to make your boobs look bigger.

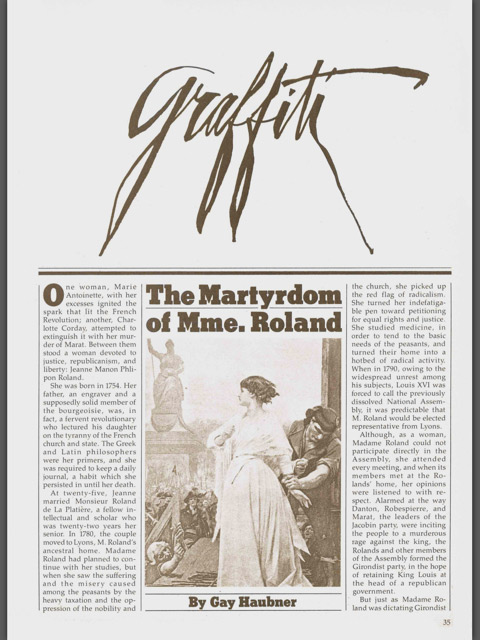

The sex advice column was replaced with features on notable but forgotten women in history, called, of course, “Her Story.” I managed to corner Viva editor Gini in the art department after days of bird-dogging her, toting around a tome on the French Revolution.

“Gini, have you heard of Madame Roland?” I asked and showed her an engraving of one of the most important thinkers and salon hostesses of the French Revolution; the engraving portrayed Madame Roland bravely ascending the steps of the guillotine (sent there by her male oppressors).

Rowan Johnson, Viva’s art director, looked over and realized that here was camera-ready art and therefore one less thing for him to do: “Yeah, Madame Rolaid, everyone’s heard of her, she’s famous in South Africa,” he said, and toddled off to lunch.

Gini gave her grudging consent to yet another secretary-written article, and I had my second byline in Viva. And despite my bad reputation as a mere secretary and a fake Pet, I began to worm my way into the good graces of the Viva staff.

Except for the fearsome Anna Wintour, the fashion editor. Kathy Keeton once asked me to deliver some notes about the fashion pages to Anna Wintour. I tiptoed up to her always closed office, thinking “Thar be dragons here.” To my surprise, my tentative knock (I was going to rap softly once and then dash back to my cubicle) was answered by a cracking of the door and a sliver of Anna Wintour’s face appeared, the part with the nose she looked down on me with. “Yes?”

I apologized for having to interrupt Miss Wintour with written instructions from our boss. Anna responded with an expression telegraphing no, she could not possibly read anything written by such a person as a South African. I backed off, curtsying my way down the hall, when she said, “I have this jacket,” and stuck her right hand out the crack of the door, holding on the crook of her index finger a brown and ivory houndstooth. “Maybe you would like it. I was going to give it to my maid.” It was an Yves St. Laurent and I wore it wore for twenty years.

I had barely snatched up the jacket when Anna shut the door on my face. I slipped Kathy’s hand-written pages under the door and immediately heard the rustling of paper being trod on by high heels.

(In 1979 after the tax break ended and Viva shut down, we broke into Anna Wintour’s office. It was a treasure trove — racks of designer clothes, shoes, and handbags, and bins of cosmetics, lotions, and perfume. The stuff was piled to the ceiling, as if the Collyer brothers had been fashion victims. It was a fluke that Anna had given me that Saint Laurent jacket, as apparently she never parted with as much as a lipstick.)

By the time I got back to Miss Keeton, she had forgotten about her notes to Anna Wintour and was in the grip of a brainstorm:

“Gay, get me Gini and that beauty woman, Suzanna. Oh, and…Anna Wintour” here Kathy looked off in the air, as if trying to will Anna Wintour to appear.

I was not about to go back to the lioness’s den.

“Miss Keeton, I just dropped your notes off. Anna wasn’t available.”

Kathy sighed, out of relief or frustration, I couldn’t tell. “Well fetch that round-faced girl who works for her.” That would be Georgia Gunn, Anna Wintour’s lackey and a lovely person.

Once I gathered everyone in Miss Keeton’s office, I headed back to my fishbowl.

“Wait Gay,” commanded Kathy. “I want you to stay.”

Was this it? Was I being promoted to the editorial staff?

Kathy spoke slowly as if announcing the discovery of the double helix. “Viva…is…going…to…”

Run recipes? Go back to naked men? Shut down completely?

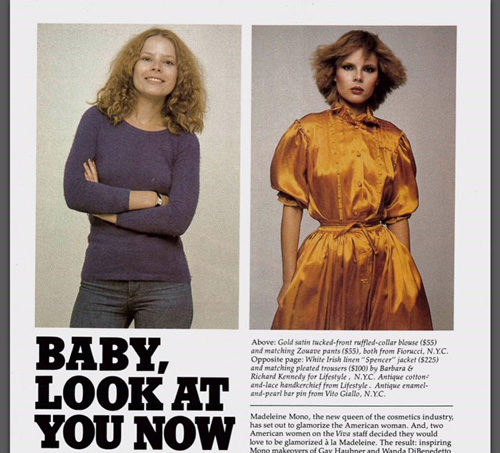

“Do a makeover.” Kathy sat back and awaited the accolades. I was the only one who beamed and smiled; nobody in that room had the nerve to tell Miss Keeton that even in 1978, the makeover was not a new idea; women’s magazines had traded for years in the ugly duckling business.

“Two actually. We’ll makeover Gay,” she ordered, pointing at that insignificant person badly in need of a haircut who was standing in the back, arms full of page proofs, mouth hanging open. “And that little brunette girl of Rowan’s” meaning the art director’s assistant, Wanda DiBenedetto. And that was all; we were dismissed to carry out Kathy’s demands.

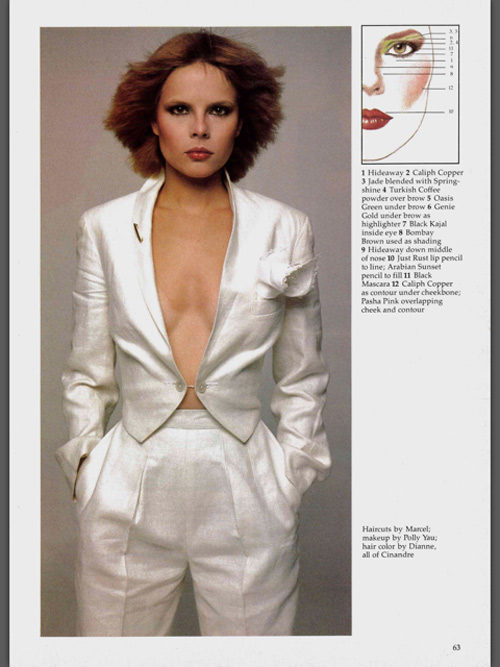

A week later I had a day off from my secretarial fishbowl and telephoning perverts, a day spent in a photo studio being transformed from frumpy and cheerful to Green Steel. The new me looked like a sawed-off villainess in a made-for-TV spy movie.

After loading about ten pounds of slap on my face, the makeup artist finished her work by smearing on a lipstick the exact shade of my outfit: a gold satin shirt and matching knickers. After a costume change, the makeup woman was called on again to brush contour shadow on my chest, in a bootless attempt to make it appear that I had two real breasts under the man-tailored jacket.

I tried not to take those gold satin knickers personally. Georgia Gunn told me Anna Wintour had been so offended by the trite, hackneyed, boring makeover idea that she had refused to take any part in it. Plus it was not being shot in Marrakech or Tahiti.

Georgia, caught between Kathy Keeton and Anna Wintour, Scylla and Charybdis, brought the clothing to the shoot, threw it in our direction, and spent the rest of the time hiding in a corner.

The day after my makeover shoot, Stephanie Coombs announced her resignation; she had landed a book contract and was on her way to becoming a full-time writer. Hoping that I was still basking in the twinkle of the diamond bracelet, I approached Miss Keeton on bended knee and asked for the now-open assistant editor position. I got it.

That issue of Viva, where I was transformed into a cut-rate Morgan Fairchild, was where my name first appeared on the editorial masthead.

My freelance for Oui prepared me for my slight responsibilities as assistant editor. Like Oui, Viva ran 10-12 short pieces in the front of the magazine promoting new books, music, places to go, things to eat, stuff to put on your hair, face, and body — except for “NO CLOTHES” as decreed by Anna Wintour; she would have had my guts for gaiters if I encroached on her fashion kingdom by so much as a hat pin.

I also accommodated the despondent Viva ad saleswomen, further befuddling the Viva reader by plugging cameras — “The Single Lens Reflex for the Single Girl,” stereo equipment — “Speakers for the House,” cheap foreign cars — “Drive Him Crazy,” and booze — “Cocktail Tease,” lifting copy directly from press releases and hoping I’d find a Technics turntable or a bottle of Galliano or a small Subaru delivered to my desk as my reward.

My goal was to get free stuff. I had barely got to taste the chocolaty fruits of my original Viva article. The first things I wrote as a real editor, even if only an assistant one, was on Viva letterhead to record companies telling them that my new position would include music reviews. The albums duly arrived, as did the occasional pair of concert tickets. Haircuts and manicures cost me only tips, because I wrote about new styles and trends from NYC’s “top” salons — the salons that colored my hair and scraped my foot calluses for free.

Whatever was fashionable in beauty, food, music, nightlife, Viva’s readers found in my little section, “Tattler,” three months after it had already passed out of style in New York City.

North Country Girl: Chapter 63 — Chocolate, Bars, and Bears

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

My tenure as secretary to Kathy Keeton, publisher of Viva and associate publisher of Penthouse, had been a wild mouse of a ride. The man who hired me tried to coerce me into sex, I had been an ignominious failure as a fake Penthouse Pet, and now I had attained almost human status in Miss Keeton’s eyes by finding and returning a $50,000 bauble her jeweler had dropped in her office’s white shag carpet.

There were few beings Miss Keeton deigned to speak to civilly: Bob Guccione, Pets, Viva ́s art director Rowan, her jeweler, the Rhodesian Ridgebacks, and advertisers, existing and prospective. For everyone else, Miss Keeton had perfected a look and attitude that relegated them to the status of bad waiters, or even bad busboys. If you were a mere editor, she had the ability to speak to the air in front of you while simultaneously staring through you.

But for the first time Kathy looked in my direction when she tossed off her demands and occasionally said please and thank you as if she might mean it. A few days following the affair of the missing tennis bracelet, she popped her head into my cubicle.

“Gay. I recall that you had some writing in your background. Would you be interested in doing an article for Viva?”

This reward for the return of the bracelet was almost as good as the diamond stud earrings I had been hoping for.

“Oh yes, Miss Keeton! I’d love to!” I gushed, praying that the assignment would not be something like “How to Find Your Own G-Spot” or “Are You Bi-Curious?” or any other supposedly erotic claptrap that would lower me even further in the eyes of Viva’s editorial staff.

The article I was to write was not about sex. It was about the next best thing: chocolate.

Viva’s advertising department was desperate to have something in the magazine they could tote around to media buyers at ad agencies that said “Look! No more penises! We’re not hardcore porn, just a regular woman’s magazine!” The delusional saleswomen wanted Viva to run an article on chocolate, in the hope that they could lure Nestlé or Hershey’s into the magazine. They convinced Kathy, who dropped into the next editorial meeting to strongly suggest that a story on “The Joy of Chocolate” be published ASAP. The editors, equally delusional in their belief that they were independent, balked at such froufrou subject matter appearing in their magazine. My sole ally, managing editor Debby Dichter, hinted to Miss Keeton that I would probably love to write the piece.

But the idea for an article for chocolate had banged around Kathy’s head too long, and had morphed into something else entirely, something consistent with Kathy’s belief that the Viva readers were all versions of her.

“Gay, don’t include any rubbish, no Godiva, ghastly stuff. I want only the top end, the most exclusive purveyors of chocolate.” I had my title: “Haut Chocolate.”

This writing assignment made me happy, but it did not make me any new friends. Viva’s editors, who tended to be politically to the left of Castro and who were never quite on my side to begin with, hated having the ad staff dictate what articles should run in the magazine. The fact that I was writing this puff piece — Miss Keeton’s secretary! — made it even worse.

What made up for my pariah status was the discovery that when you work for a magazine, you get free stuff.

All it took was a few phone calls and I had boxes and boxes of beautifully crafted and utterly delicious truffles and pralines from Teuscher and Neuchatel and other European chocolatiers messengered to me. I made a small uptick in my reputation by personally delivering each box to a different Viva editor. Then I called and requested more gift-wrapped boxes of chocolates to photograph for the article.

I did not fare as well with the ad saleswomen. Beverly Wardale, the alpha female of that wolf pack, showed up at an editorial meeting shaking the layouts of my article.

“What the bloody hell is this?” she demanded. “These companies don’t advertise! You can’t even buy these bloomin’ chocs anywhere except Fifth Avenue and Switzerland!” The editors all cut their eyes at Kathy, and Beverly, realizing that the article had Kathy’s chocolaty fingerprints all over it, departed in a huff, tossing the pages behind her.

***

I had been at Viva long enough to accumulate a week’s paid vacation, but I had not accumulated the money to pay for a trip anywhere, unless it was via subway. My artist boyfriend, Michael and I were pretty much living on my $12,500 secretarial salary. The monthly check he received for his illustrations in Esquire magazine went right back out the door in the form of child support for his two kids back in Chicago.

Michael was starting to get illustration assignments from astute art directors who recognized his uncanny ability to capture personality in his portraits. He did not draw caricatures; he drew character. Michael’s genius was his ability to express in a few black lines and a charcoal wash the inner person. Michael could see, wanted to see, below the skin, past the face one presents to the world, and he looked with equal parts of empathy and curiosity.

Michael approached everyone with a wide open heart and whip-smart intelligence. He wanted to know what made them tick, what they liked, what motivated them. He was able to find common ground with anyone: he could talk sports, art, music, books, and movies, and was always more interested in your opinion than his own. I never introduced him to a single person who did not want to be his friend.

Both Viva and Penthouse were too slick, too air-brushed to have any use for Michael’s intellectual style of drawing. I dragged him and his portfolio up there anyway, and had him meet as many of the staff as I could buttonhole in a loop about the office. Michael’s charm turned out to be more effective in redeeming my reputation than a $100 box of truffles.

Even Viva’s editor, Gini, regarded me with a less jaundiced eye after she met Michael. Her own boyfriend, Bill Plympton, was also a cartoonist and illustrator, although a considerably more successful one than Michael.

My first friend at Viva, Debby Dichter, had long been a fan; she may have had a small crush on Michael. One night at dinner, Michael confessed to her, “I feel terrible” (he did, Michael was really really good at guilt) “that I can’t afford to take Gay on a vacation. She deserves it,” and he looked at me as if I were the moon and the stars.

Although I had mentioned our lack of funds to Debby on the few occasions it was my turn to complain about something, to please Michael Debby now sprang into action.

“My family has a house on Cape Cod, in Wellfleet. You could use it. It wouldn’t cost you anything.”

Michael and I set off in a borrowed car to a borrowed house, which turned out to be the perfect Cape Codder: an elegant two-story modern home, all glass and wood, set on a thickly treed lot, no neighbors in sight. I was thrilled, as was Michael, until it started to get dark.

Michael peered into the crepuscular forest and shuddered.

“There’s nobody around. What do you think is out there?”

“Owls, sleeping chipmunks…”

“Bears?” asked Michael. Up till now, to Michael a bear meant a burly man wearing a football helmet (or his young baseball playing relative, a Chicago Cub). I had grown up in a town that was a regular commute for bears; the classy Hotel Duluth had The Black Bear Lounge, as one had once wandered through the lobby, a bear in search of a beer in a bar.

“Michael, the closest bear is probably in the Boston zoo.”

“There are other big animals though,” worried Michael, as dusk erased the space between the trees, leaving only a few birches glowing like skinny ghosts. “Like ah, moose…moose and…”

“And squirrel?” I said in my best Boris Badenov voice. It didn’t help. Michael turned on every light in the house, including the garage and the back door. The master bedroom, with its big windows and woodsy view, was on the ground floor, too close to marauding squirrels; we slept in the attic, sharing a twin bed under the gleam of a Tinkerbell nightlight.

Michael was much happier in Provincetown, with its paved streets, stores, restaurants we couldn’t afford, art galleries that were not yet open for the season, and bars. He especially liked one bar that offered a 10:00 a.m. happy hour to accommodate the fishing crews. We ended up spending most of the day in that bar, a day I had planned on visiting the famous Cape Cod dunes, my goal a pilgrimage to the primitive (no electricity, no running water) shacks where Norman Mailer, Jackson Pollock, Eugene O’Neill, and Tennessee Williams had created masterpieces. Michael had agreed to this plan, but it was now almost three o’clock and I had reached my tolerance for day drinking.

We arrived at the dunes at the exact moment when the western light casts a weird spell over the lunar landscape, flinging deep violet shadows across that treeless spit of land, flattening everything out, and warping perspective; it was like being in a real-live Mystery Spot. We could see one shack on top of a nearby dune; after a half-hour trudge through the sand, the shack actually seemed farther away.

Michael turned around. The only sign of which direction we had come from were our footprints, slowly filling in with sand.

“We’re lost!” Michael freaked out. Outside of that gray, dilapidated cabin, which was either a block or a mile away, there were no man-made objects in sight.

I could not take this seriously. “At least there’s no bears,” I ribbed him. Michael looked at me as if I were a heartless monster who had lured him to this death trap.

“C’mon Michael, you have got to be kidding.” He wasn’t. “Cape Cod is like a mile wide here. It’s impossible to get lost, we walk one way and we hit the sea, the other and we hit Highway 6.”

“Or we could just walk in circles till we die.” I gave up, took Michael’s hand and, turning our backs to the setting sun, we returned to the parking lot and then on Michael’s insistence, back to the Fisherman’s Arms. He desperately needed a drink.

By the end of the week, Michael had spent so much time in that bar that he was practically an honorary fisherman, having charmed even the crabby old lobstermen. He justified his bar tab by the fact that when I came to pick him up after my solo visit to the Pilgrim Spring or retracing Thoreau’s Cape Cod walks or bird-watching at the kettle ponds, he was not allowed to leave without a flounder or haddock or pair of lobsters for our dinner. I gave a silent thanks to the gay waiters at Arnie’s back in Chicago for teaching the lowly coat check girl how to bone a Dover Sole and crack open a lobster.

North Country Girl: Chapter 62 — Diamonds are a Secretary’s Best Friend

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

My role as a replacement for Shonna Lynne, April’s Pet of the Month, at a Penthouse-sponsored race in upstate New York, was not my shining hour. Cy Preston, the Pet wrangler and an honest PR guy, was as good as his word; Miss Keeton never found out that I was a complete failure as a fake Pet, looking more like a drowned rat. But by Monday, the day after the race, the office rumor mill was already in motion.

“You posed as a Pet?” Debby Dichter took time out from her daily melt-downs over late copy and art and ads to interrogate me at my desk, while I compulsively scratched the hives on my neck; I had spent my day at the races inside the Penthouse hospitality tent, seeing how many shrimp I could eat. “I can’t believe it,” she chided.

I could see any hope for a promotion to the editorial staff evaporating. Every Viva editor was a feminist of some ilk, from Stephanie Coombs, who had bravely outed the sexual predator and former managing editor, Bernie Exeter, and moved up the editorial masthead; all the way to the fierce Martha Lorini, the fiction editor who smuggled stories by Gail Godwin, Doris Lessing, Renata Adler, and other fire-breathing authors into Viva. All of them clung firmly to their feminist credentials, despite the fact that their salaries were paid by a blatant exploiter of women. The Viva editors were a coven of tough, intelligent women I admired and longed to be part of, a group who dismissed me as a lightweight.

I managed to keep Debby as a friend and supporter after I took her out for a drink after work and told her the whole sad, soggy tale. She commiserated for thirty seconds before launching into her usual complaints about the impossibility of ever getting Viva to the printers on deadline.

“Even if the editorial is all in, even if the ad saleswomen finally give up hope that General Mills is going to take out a full-page ad for Cheerios, everything comes to a screeching halt at the art department. Effing Rowan.”

Rowan Johnson, the always drunken or drugged up (it was impossible to tell the difference, so deeply did he plunge into altered states) and preternaturally talented Viva art director, was, like Kathy Keeton, from South Africa. They had bonded over their shared homeland back in the London offices of Penthouse, even though they differed on apartheid. Kathy was completely for it: there was not a single black employee at Viva or Penthouse, and when Bishop Desmond Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize, Kathy dispatched reporters to South Africa to “dig up the dirt on that Kaffir.”

Rowan also saved the day when Kathy, reviewing the layouts of an already insanely late issue of Viva, discovered that Eartha Kitt, who was profiled in that issue, was black. The shriek that Kathy Keeton let out when she saw the full-page photo of Miss Kitt (who insisted on the “Miss” honorific for herself every bit as much as Miss Keeton did) sent most of the editorial staff off to hide in the ladies’ room. Rowan was summoned to explain to Kathy how this horrid thing had happened and to make it go away. Thankfully this occurred early enough in the day that Rowan was able to string a few words together coherently and he managed to talk Kathy down. He had done some of his best work on Eartha Kitt’s photos and the layout and didn’t want to have to create something entirely new two weeks after the issue was due at the printer.

Despite Rowan’s belief in equal rights, Kathy adored him. She herself had brought him over from London to work at Viva.

I use the word “work” with reservations, as Rowan usually got to the office at eleven, went to lunch at one, and came back at four completely incapacitated. It had been whispered that Rowan came into work one weekend a month with a goodly supply of cocaine and laid out an entire issue of Viva in two days.

The biggest responsibilities of my secretarial days were 1) to immediately notify Kathy when the phone rang and a nasal voice said, “I have Mr. Guccione for Miss Keeton,” and 2) to keep track of Rowan. Kathy Keeton would be bored or lonely, or she decided that she hated a photo or illustration and it had to be redone immediately, or she’d want Rowan to help her pick out a new piece of jewelry, or she would have heard from Debby Dichter that it was now costing a thousand dollars a day to hold the printing presses past Viva’s absolute last deadline.

“Gay, get me Rowan,” she ordered. A phone call to the art department did not work; anyone who answered automatically said, “Rowan’s not here” and hung up. I had to hunt him down like a big game trapper after a wily creature. If I was very unlucky, he would be in his office with the door locked. I’d slip a note under the door, knocking and yelling, “Rowan! Miss Keeton wants you!” (never a response), beg the art staff to tell Rowan to stop ingesting or injecting whatever and come down to the other end of the office, and was then forced to dawdle about the halls, not wanting to face the wrath of Kathy by coming back empty-handed.

Between one and four, I knew where to find Rowan: across the street at P.J. Clarke’s, a single-story speakeasy left over from the 1920s that stubbornly hunkered among Third Avenue’s glass and steel skyscrapers. It had bare bones décor, a famous hamburger, strong drinks, and red-nosed, craggy faced bartenders who did buy backs every third cocktail. I’d walk into the bar, which reeked of spilled beer, cigarette smoke, and charred beef, and find Rowan wobbling on a stool, drinking his lunch. The task of removing Rowan from that barstool was made even harder because I felt so sorry for myself: I had no work friends to have a Clarke’s burger and Bloody Mary with. My only pal, Debby Dichter, chowed down a sandwich at her desk so she could get back to haranguing the Viva staff.

If I was very lucky, I would find Rowan mooning after Anna Wintour, the fashion editor. She too spent a lot of time behind her locked door; Rowan would linger outside her office, hoping for a glimpse or a word with his idol. Anna, however, looked at him as she did everyone around her: as if he were something on the bottom of her Charles Jourdan shoes. Even Kathy, whose own looks could curdle milk, was intimidated by Anna. It was all I could do to not tug on my forelock when Anna sauntered past me and into Kathy’s office, never waiting for an invitation, to demand more money to hire pricey photographers and ship them and half a dozen models (as well as Anna and her long-suffering assistant) to an exotic locale half way around the world. Kathy always gave in, forcing Viva even deeper into the red, in the forlorn and ludicrous belief that the Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar advertisers, Revlon and Dior and Blackglama, or even the humble L’Eggs panty hose, might be fooled into buying ads in the former penis magazine.

When not hunting down Kathy or Rowan, I sat in my fishbowl and willed the phone not to ring. The idiot at the switchboard refused to screen incoming calls or even ask the caller’s name or business. I would answer the phone “Miss Keeton”s office,” and there would be the heavy breathing noises of a weirdo or some guy with an urgent message for a Pet. I have no idea why I wasn’t allowed hang up; so what if Penthouse lost a reader, there were still 4,999,999 men plopping down their $1.50 for the magazine each month.

Along with her official titles of Viva Publisher and Penthouse Associate Publisher, Kathy also served as the Pet Closer. Every month or so, a shy, scared girl with enormous breasts and a pretty face would show up: “Um, ah, um, I have an appointment? With Miss Keeton?” I escorted the new meat into Kathy’s presence; she was no longer Ice Queen; she was now Benevolent Older Sister.

“Gay, we’d like some tea,” she ordered, not bothering to remember the girl’s name as she patted the cushion of the love seat, encouraging the terrified girl to sit next to her. I steeped and poured and set out sugar cubes and fetched milk from the dorm fridge that shared my fishbowl and eavesdropped on Kathy’s spiel.

These were the only times Kathy alluded to her own humble beginnings at Penthouse, in photos of her wearing nothing but ballet toe shoes. No one else was allowed to mention this and all copies of the issue of British Penthouse Kathy appeared in had mysteriously vanished.

Kathy’s job was to convince this 19-or 20-year old rube that the best thing she could do for her modeling/acting career was to spread her legs as far apart as possible for Bob Guccione’s camera. Pimps at the Port Authority Bus Station could have learned persuasive techniques at Kathy’s knee.

“Look at me,” Kathy confided, leaning in a bit closer to her victim. “I was a poor, struggling ballet student. I never dreamed of having a mansion, a limo, all of this” — indicating her gilded boudoir of an office with a heavily jeweled hand. Despite the fact that Marilyn Monroe was the last actress to launch her career through porn, way back in 1953, Kathy convinced these poor girls that showing off their gynecological goodies was the first step on the road to Hollywood stardom.

In the end, the girls fumbled around with their dainty china teacup, thanked Miss Keeton, and dutifully headed over to the House to be photographed by Bob Guccione.

It was hard not to be impressed with Miss Keeton’s gold and gems; I learned that the rings and bracelets and earrings she sported could be categorized by Sotheby’s auction house as “Important Jewels.” These pieces might have been tasteful if worn individually; Kathy piled them on and glittered like a disco ball.

Miss Keeton did not patronize Sotheby’s or Tiffany or Bulgari. Her jeweler came to her. He was an elderly small gentleman in a worn black suit, burdened with an oversized attaché case, Old World gracious and soft-spoken. Behind his Coke-bottle-thick rimless glasses his watery blue eyes still flashed the occasional glint, like the star in a sapphire.

I lingered over the tea-making and paper-gathering to ogle at what was in the jeweler’s case. After bowing to Kathy, the jeweler spread a jet black swath of velvet on top of the French Provincial coffee table. He intoned “24 karat,” “platinum setting,” “rare South Sea pearls,” “Burmese rubies,” like the words of a prayer, and gently set down each jewel as if he were placing gaudy constellations in a night sky: lion head door knocker earrings, the lions’ eyes round-cut emeralds; a gem-encrusted medallion with a heavy gold chain that would inspire envy in Kanye; a tennis bracelet, a string of chickpea-sized diamonds that would have blinded an opponent on the other side of the net; and rings with such gargantuan center stones they could double as knuckledusters. Kathy’s office was transformed into Aladdin’s cave.

Kathy dismissed me with a wave of her hand, but through her open office door I watched her try each piece on, while the jeweler murmured his approval. She took most of them, although no money or jewelry changed hands, usually adding an order for another gold chain for Bob or for one of the Rhodesian Ridgebacks.

The jeweler packed up his case, kissed Kathy’s hand, and came out to thank me with a handshake as soft as a cat’s paw. Kathy left an hour later without a word to me; I knew my duties. I turned on the forbidden overhead lights in Kathy’s office to ensure that when I was done everything was pristine for her start the next morning: no loose paper, no forgotten tea cup, making sure that her Mont Blanc pen, Virginia Slims, and a sparkling clean crystal ashtray were the only things on her desk. Under the glaring fluorescent lights, I saw a twinkling in the white shag carpet.

It was the tennis bracelet. This was a new concept to me — sports jewelry! — and I was enamored. I draped the bracelet over my left arm and grappled with the clasp, which was beyond my uncoordinated fingers. It was a bracelet a lover should put on you, finishing with a kiss on the pulse of your wrist.

I have a larcenous soul. I had boosted my sophomore year wardrobe from the clothing store I worked at, as did every other salesclerk (and probably the mail man and the meter maid); stealing seemed to be employee policy. And even unclasped, the bracelet looked so pretty on me.

But like so many mysteries from that time, I don’t know why it never occurred to me to keep the tennis bracelet. I took it back to my cubicle, dropped it in the top drawer, next to my pencils and paper clips and staple remover. I found the jeweler’s phone number in my Rolodex and called.

“Hello, this is Miss Keeton’s office. Could you please tell Mr. Jacobs that he left something here?”

Thirty minutes later, the little man showed up, breathless and red and looking as if he were about to have a heart attack. I sat him down on my chair, put the bracelet in his hand, and rushed to get him a glass of water. When I returned he was mopping his brow with a large handkerchief and slipping the bracelet into his jacket pocket, which did not seem to me the safest place for a just recovered $50,000 piece of jewelry.

It occurred to me later that I was due a small thank you piece of jewelry, maybe half carat diamond studs? I did receive a very nice thank you card from Mr. Jacobs. And that old mensch did me a solid: he called Kathy and told her that I had found and returned a Very Important Piece of Jewelry, especially important as it was one of the items she purchased.

Because of that, in Kathy’s eyes I was now almost a person.

North Country Girl: Chapter 61 — The Flying Fake Penthouse Pet

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Some names have been changed.

I had landed my first job in New York: secretary to Kathy Keeton, publisher of on-the-skids Viva magazine, sister publication to the notorious and extremely successful Penthouse. Viva was one of my favorite magazines, and my salary was enough keep the wolf from the door of the Lilliputian Chelsea apartment I shared with my artist boyfriend, Michael.

There was one catch. According to managing editor Bernie Exeter, who had hired me, if I wanted to keep my job I had to sleep with him. Under this threatening black cloud, I was reduced to a wreck of a secretary, concentrating mostly on avoiding Bernie. Thankfully my responsibilities did not go much beyond answering the phone, making cups of tea, and fetching cigarettes for Miss Keeton.

Before my first wretched week at Viva was out, Debby Dichter, the assistant managing editor, who was friendlier to me than anyone else, popped into my cubicle with her usual mass of papers and an “I’ve got a secret” smirk.

“Don’t say anything to anyone else but Bernie’s been fired. I’m the new managing editor.” I swallowed and breathed and croaked out something between a “What?” and a “How?”

“Stephanie Coombs, the editorial assistant, you’ve met her, she’s young and blonde, like you. Bernie told her if she didn’t sleep with him he’d get her fired.” Debby’s eyes widened at such villainy. “Ugh, I mean can you imagine. Stephanie laughed at him and went right in to see Kathy.”

I now remembered: Stephanie had showed up unannounced the day before, saying “Sorry, Miss Keeton. It’s important. Can I shut the door?”

Debby continued, thrilled with her juicy tidbit. “Stephanie told Kathy what Bernie said to her. So Bernie’s fired and Stephanie’s new title is assistant editor.”

My relief was a physical lightening, as if I had been carrying around an incubus who suddenly pulled his teeth from my neck and flew away. Then I was furious, mostly at myself. Could it have been that simple? Did I just miss out on a promotion from secretary into the vacant editorial assistant slot? It was too late now. I couldn’t raise my hand and wail, “Me too, Miss Keeton, me too!”

It took a few hours for my mind to process the most important lesson: It wasn’t my fault. Whatever sick, misbegotten idea I had that when men acted like assholes it was because of something I said or did or how I looked, even as an eight-year-old being molested in Goldfine’s toy department, was wrong. It wasn’t me. It was them. Evil Bernie thought he had the power to bully young blondes into sex until one of them laughed in his face and busted him.

The waves of emotions had wiped me out by the time I got home. I just wanted to sit on our tiny orange couch in our sloping apartment and have Michael hold me. “Is everything okay?” he asked. “You’ve been so strange. Do you hate the job? You can quit. Well, maybe you could find another job and then quit…”

“I’m fine,” I said and made him stop talking with a kiss.

I was fine. I liked Miss Keeton, even if I felt like a combination zookeeper and handmaiden to this glamorous creature from another world. I was slightly in awe of the editorial staff, some of whom treated me like the secretary I was, some of whom acted as if I might be their equal, and one of whom, Debby Dichter, now elevated to the even more frantic managing editor position, seemed to want to be my friend. Debby knew everything that was going on not only at Viva but also at Penthouse magazine; she and her Penthouse counterpart spent hours commiserating on the inability of anyone to ever get anything in on deadline.

Debby made Chinese food for Michael and me in her Upper East Side studio; over sesame noodles she dished about the magazine. Debby was not as confident as Bernie Exeter had been about Viva’s future.

“Just look,” she said, opening the current issue. “Other than the cigarettes, there are no paid ads! This,” pointing to an ad for Frangelico liqueur, “was free ‘cause they bought an ad in Penthouse. I have to keep pages and pages of Viva open every month, in case a miracle happens and someone sells an ad. That’s why there’s this,” she said, stabbing a photo of a pouting, bare-breasted woman in a big straw hat and pearls, a full-page ad promoting Penthouse magazine. “And this,” turning to an ad for Penthouse Forum, a Reader’s Digest-sized magazine for material too filthy for Penthouse itself. “Otherwise we’d be running blank pages every month.” Debby closed the magazine in disgust. “Viva could have recipes for apple pie and articles on the joys of motherhood, and we’d still be the penis magazine; we’re losing millions of dollars every year. You’ll be okay, you’re Kathy’s secretary.” I flinched. “But the rest of us?”

As managing editor, Debby was a professional worrier. But Viva was only kept alive because of the cascade of cash generated by Penthouse.

Money poured in faster than it could be spent. Bob bought a museum’s worth of art to fill The House (we were never allowed to call it a mansion, even though it was the largest private residence in Manhattan; mansion smacked too much of the Playboy universe); Miss Keeton bought jewelry and a trio of enormous, hideous, pedigreed Rhodesian Ridgebacks that were prone to attack guests to The House and could only be controlled on their walks to Central Park by Guccione’s mobbed up chauffeur, Guy.

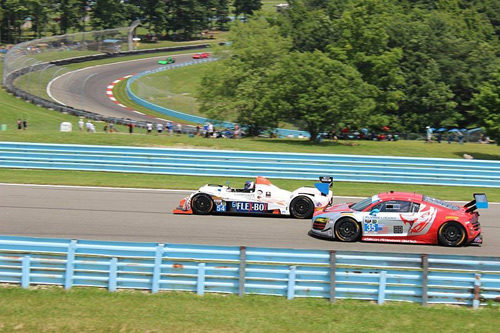

Even though neither Bob nor Kathy ever showed any interest in automobiles unless they were Penthouse advertisers (a tiny contingent of Asian car manufacturers), Penthouse also sponsored a Formula One race car, driven by the International Motorsports Hall of Famer, Stirling Moss.

One Friday, a few weeks after my escape from the lustful, lubricious Bernie Exeter, Miss Keeton called me into her office.

“Gay, I need you to work on Sunday.”

“Yes Miss Keeton.” I didn’t mind. I was even a bit excited. I imagined that working on Sunday meant that I would finally get to see the inside of The Guccione House (if I didn’t get my throat ripped out by Ridgebacks) and its fabled masterpieces, including, according to Debby Dichter, a Picasso hanging above the basement swimming pool.

“Guy will pick you up, very early I’m afraid, to get you to the airport on time.”

Wait, what? “Yes, ah Miss Keeton?”

She waved a hand at me, her version of “Shut up.”

“Wear that…that ‘outfit’ you had on the first day.” She was alluding to the fatal Kenzo tunic and harem pants I wore when I met Bernie Exeter, an outfit that laid crumpled on my closet floor, a painful reminder of my stupidity. “And,” here Kathy wrinkled her elegant nose as she looked down it at my ankle boots, “Nice shoes. Something with a heel.” Kathy, who never had to race down subway stairs to catch a train, lived in strappy, glittery stilettos.

I was mystified, stunned into silence. Kathy sighed, and deigned to explain.

“Shonna Lynne is sick. Well, she claims she’s sick. You’re going to take her place.” Shonna Lynne, who went on to star in I Need 2 Black Men and Deep Throat Girls 11 was April’s Pet of the Month; she had two large assets I did not. Kathy seemed to have the same thought and her eyes briefly rested on my chest. She said, “You’ll be fine, that other blonde girl is going too,” and I was dismissed.

I was going to be a Fake Pet. Shonna Lynne and a dozen other real Pets were kept around to pretty up The House, promote Penthouse, and amuse (in many ways) advertisers. These girls, despite their sultry, wide open photos in the magazine, always started off eager to please; they still believed that they had just gotten their first big break and did everything they were told, sweet obedient puppies.

As the months passed, and Hollywood kept refusing to call, sadder but wiser Pets would clue the newbies in that their real future was not on the big screen, but on the small stage at strip joints, where they could earn $1,000 a night. Once the Pets were raking in the dough, when their presence was requested at a trade show or dinner with a potential advertiser, Shonna and her ilk were no longer available. One would think that being a Pet meant having sixteen near-fatal periods a year, a stomach highly susceptive to food poisoning, and at least eight deathly-ill grandmas.

I had not realized that posing as a Penthouse Pet was part of my job description; I can’t imagine that the sullen brunette I replaced as Miss Keeton’s secretary was ever asked to don the “Penthouse Pet” sash Cy Preston, Penthouse’s PR guy, handed to me as I scrambled into the limo at six in the morning on that freezing cold, pouring rainy Sunday.

Along with the gnomish Cy, who I knew from his weekly meetings with Kathy on the “Viva Problem,” there were six girls, all as gloomy as the weather; one of them, a blonde with a chest as unimpressive as my own, I recognized; she worked in the opposite end of the office from me.

“Mr. Preston,” I ventured. “Where are we going?”

“The race,” he answered, then realized that Kathy had told me nothing. “Elmira. Watkins Glen.” I blinked blankly. “Stirling Moss. Formula One. We’re hosting a big party, flew a bunch of advertisers and circulation guys up there yesterday, all you have to do is walk around, look pretty, act nice. And if you don’t get too drunk, you might get to wave a flag, but we’re counting on Vicki.” Here Cy waved at a dozing redhead; she was Penthouse royalty, The Pet of the Year, Vicki Johnson.

I had only a rudimentary grasp of New York geography, but I knew, as I looked out the limo’s dark tinted windows through the now Noah’s Ark level downpour, that we were leaving Manhattan, headed for New Jersey. The other girls in the car were asleep, with the exception of the sullen blonde from the office who was smoking a cigarette as if she hated it. I was about to introduce myself, when she scowled at me through the menthol smoke.

We pulled into a small airfield, the limo drove right up to a plane, and Cy Preston escorted us one by one on board, shielding our (well, everyone else’s) elaborately styled hairdos and carefully applied cosmetics under his umbrella. We took off, headed north into even more rain, and within the hour, descended through the dark grey clouds to an even smaller airfield, where we were decanted into a pair of Lincolns under a monsoon that flattened everyone’s hair and washed away the layers of makeup and turned Cy’s umbrella inside out.

“It looks like you girls will have time to get pretty again,” said Cy, looking out ahead at an endless queue of motionless cars; we were as deadlocked as any traffic jam in Lagos or New Delhi. In the time it took to drive half a mile, we girls could have gone through a dozen different wardrobe changes. Cy kept looking at his watch, rolling down the window to stick his head out, to the shrieks of those of us getting soaked in the back seat, and muttering to himself.

I don’t know why the Pets weren’t brought in the night before; money could not have been an issue. But now, despite the blast of chilly air every time he opened the window, Cy Preston was sweating bullets. At this rate, we’d be lucky to make it to the track in time for Vicki to wave the checkered flag signaling the end of the race.

“I gotta get to a phone,” Cy instructed the driver, who pulled out of the endless line of traffic and into a gas station. Fifteen minutes passed before Cy reappeared, drenched to the skin.

“You know where the high school is?” Cy asked the driver, who nodded and headed back the way we had come, followed by the second car. We ended up by the school’s football field, in the parking lot behind the bleachers. Everyone but me smoked as we waited for something.

This is where I cue “Ride of the Valkyries” in my inner movie, accompanied by a “whump whump whump,” first barely heard over the pitchfork rain that became louder and louder, until from out of the leaden sky onto the football field descended an Army helicopter. Cy had called in the troops.

Out of the helicopter jumped a man in uniform and helmet, who dashed over to our car, crouching close to the ground. Cy rolled down the window. “Mr. Preston?” the soldier asked, while getting a good look at the Pets huddled in the back seat. “We’ll get you to Watkins Glen in a jiffy. Now y’all gotta be real careful when you run to the copter, hunch over so the blades don’t hit ya.”

With this encouragement, I followed Cy out of the car and immediately sunk up to my ankles in mud, my high heels vanishing beneath the sodden grass. I leaned on a thrilled soldier to extricate my feet from the mire, took off my ruined shoes, and ran barefoot to the helicopter.

When we were all on board, the pilot turned around with a mile-wide grin and said, “Wowee, who’s gonna believe this!” as excited with his cargo of Pets as if we were bare-assed naked.

The Army was all it could be. We flew over that unmoving, endless line of cars and within minutes set down in the relatively dry center of the racetrack. Cy shook hands with the pilots, crowed “Pet of the Year, guys!” and made Vicki kiss them, which she did damply and graciously. He then hustled us across the race course to where several large tents sagged sadly in the rain.

One of those tents was festooned with a drooping “Penthouse Formula One” banner; despite the crappy planning someone had actually thought to partition off a small changing area inside. “Fix yourself up, girls,” ordered Cy.

I watched the other girls whip out hot curlers, blow dryers, and makeup kits bigger than my grandfather’s tackle box. I had a lipgloss, ruined shoes, and mud-spattered white pants I would never wear again. My “Penthouse Pet” sash had somehow gotten ripped. I was too intimidated to ask to borrow a comb.

When we emerged half an hour later, the wet chicks were transformed into a bevy of (mostly) busty beauties, ready to charm the crowd — except for me. Cy sighed, took me aside, said, “I won’t tell,” and relieved me of my sash. I did not get to wave a flag and managed to avoid talking to anyone. I did position myself right by the extensive buffet table and ate so many shrimp I came up in a rash the next day.

North Country Girl: Chapter 60 — Me Too

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Some names have been changed.

With ridiculously unfounded optimism, I had sent off my resume to Viva magazine (notorious sister publication to Penthouse), and had been miraculously summoned to an interview with Bernie Exeter, the managing editor, who ever more miraculously, offered me a job. I just had no idea what the job was.

“Oh, I thought I told you. The job is secretary to Kathy Keeton, Viva’s publisher,” Bernie said.

I squeezed out a smile to hide my disappointment: I had expected to be offered at least editorial assistant. I had not a single secretarial skill and no idea of what a publisher did, but it was a job at a magazine, a magazine I loved. And my artist boyfriend Michael and I were stone broke, with no idea of where next month’s $400 rent would come from.

“Sure, yes, when do I start?”

“Right away. Let’s meet Kathy first.” Bernie hauled me up by my arm and my head swam. What was happening? Bernie seemed nonchalant about hiring me to work for someone else. What if this woman hated me on sight? We headed down the hallway, Bernie clasping my elbow as if I were a reluctant three-year-old. A glass enclosed cubicle held a sullen brunette woman who waved us into a large corner office.

The gray industrial hall carpet ended at the door of this office, and a thick swath of white shag, soft as fleece, began. The office was lit by little gilded lamps set on little gilded tables. Before a white and gold brocade loveseat was a low gilded coffee table and a silver tea service. Behind a white and gilt spindly-legged French Provincial desk sat an older blonde, her long hair held back in what looked like a painfully tight pony tail. She was dressed in an outfit that made my own inappropriate garb (sleeveless tunic, harem pants) seem as conservative as a lawyer; she wore leg-hugging ivory silk pants and a plunging halter top that looked like two scarves tied together, showcasing breasts that had no visible means of support despite their impressive size. I had often read the phrase “dripping with gold and diamonds;” now I got to see it in real life.

“Gay Haubner, this is Miss Keeton, the publisher of Viva.” I flinched at Bernie Exeter’s faux pas, as Miss Keeton, without rising or acknowledging the slight, offered me a jewel-encrusted, perfectly manicured hand.

“Miss Keeton, it’s a pleasure to meet you,” I said, trying to will saliva into my mouth.

“She’ll be great as your new secretary,” Bernie said, as he passed her my portfolio. Kathy glanced at it, asked me several questions about Oui’s circulation and ad sales, none of which I could answer, and handed the portfolio back to me.

She said, “I hope you can start right away, ah, Gay?” I nodded confirmation that was my name. Bernie Exeter, bowing and scraping, dragged me off by my elbow again, and I spent the next hour in a small interior office covered on every surface with files and papers, added my own filled-out forms to those piles, and found out that I would make $12,500 a year, and have health insurance and two weeks’ vacation. I was a grown-up.

I spent the next day smashed in with the sullen woman in the secretarial fishbowl, who took me though my duties, the most important of which was to always address my new boss as Miss Keeton.

Miss Keeton rarely wrote letters. My bad dream the night before of having to take dictation in shorthand, which I did not know, and then losing my pencil and then discovering I had no pants on, thankfully was not a premonition.

Because of her other job title, Miss Keeton did, however, receive a lot of mail, letters with “Kathy Keton, Penthouse Associte Pubisher,” written in block letters or childish scrawls on envelopes stamped with a prison or army base as the return address. Hundreds of strange lonely men just picked her name off the Penthouse masthead and assumed that she could arrange dates for them with Penthouse Pets or that that Kathy would become their pen pal.

And there were the phone calls. Back in those days when even a professional office phone system was only a slight improvement over two tin cans and a string, there was no voice mail, no direct numbers. The airhead at the switchboard, who had her job solely because she was the girlfriend of the Penthouse treasurer, automatically put through all the calls to Kathy Keeton, even the collect ones from penitentiaries.

“But you have to answer every call,” the sullen woman instructed. “And,” she added with a shudder, “you have to be nice to them.”

“Also,” she said, “the religious nuts who call threatening to kill Miss Keeton or blow the place up? Don’t worry about it. Nothing’s happened yet. Those guys, though, yeah you can hang up on them.”

I was given a few additional instructions that did not have to do with dealing with crank calls and letters. By noon I was on my own. Miss Keeton was out that day, so all I had to do was keep track of the few legitimate callers, writing down their name, phone number, and message on a small pink “While You Were Out” slip and skewering the paper onto a wicked looking spindle, an oddly satisfying action.

In the afternoon, a few members of Viva’s staff who passed by my enclosure stopped to introduce themselves. I met the “smart cookie” new senior editor, Gini Kopecki, who was dressed in non-designer jeans, wore not a lick of makeup, and had long hair of an indeterminate color parted down the middle. I met Debby Dichter, the assistant managing editor, diminutive and dark and frantic, who came by every hour with her arms full of loose glossy magazine page proofs for Miss Keeton. I met the art director, Rowan Johnson, a shaggy South African, who showed up roaring drunk at 3:30 under the impression that he had a lunch date with Kathy.

At five, I picked up my purse to go home, infinitely pleased with myself for landing this job and already wondering how long it would take me to be promoted to editor.

Bernie Exeter blocked my exit.

“Let’s go for a drink and you can tell me about your first day,” he said. I wanted to go home and celebrate with Michael in our new apartment, a minuscule one-bedroom hidden away in a Chelsea mews, the second floor of a carriage house, with six-foot ceilings and a floor that slanted so much a dropped orange would roll from kitchen to living room.

“Sure,” I said, “That would be great.”

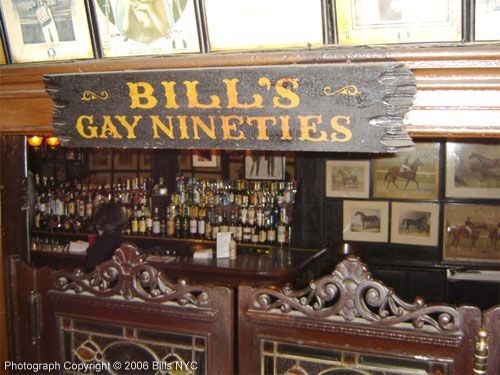

We went around the corner to Bill’s Gay Ninties, a below-sidewalk-level bar that was weirdly outdated even in 1977. Bill’s Gay Nineties was decorated like a phony saloon at a Colorado tourist attraction, a really down-on-its-luck tourist attraction that only survived because it happened to be up the road from the Cave of the Winds or Estes Park. It was a maze of small rooms, with dingy red-flocked wallpaper and dusty chandeliers, staffed by bored waiters in striped shirts, suspenders, and sleeve garters. The bartender had muttonchops and a handlebar mustache.

One drink, I thought, and some gushing about how grateful I am, and I can go home. Bernie let me rattle on and on, and even though I didn’t want it, a second drink appeared before me. I was struggling to get to goodbye, see you tomorrow, to escape from this creepy place, where gray businessmen drank alone and “Sweet Georgia Brown” crackled out of a shitty speaker.

“So,” said Bernie Exeter, “You like the job.” I thought I had made that clear over the past half hour.

“Oh, yes I can’t tell you how much I appreciate what you…”

“You can show me.”

I knew what was coming.

“Why do you think I hired you, Gay?”

Because I can write? Because I put down good money, month after month, to read Viva? Because I dress like Miss Keeton’s poor relation?

Somehow my second drink had disappeared and a third one had taken its place.

“I hired you because I want to go to bed with you. So if you like your job and want to keep it, you know what to do.” Bernie Exeter sat back and looked at me, a raven eying a semi-squashed bug.

This was not the first time I had received a tit-for-tat offer, though never so explicitly. I couldn’t even flutter my eyelashes or act as if I didn’t understand what was going on, my usual response.

“But…but…I have a boyfriend!” was the only thing I could come up with. This got a laugh and a reprieve.

“Okay,” said Bernie Exeter, finishing his drink and then mine. “Maybe not tonight. I’ll give you a few days. Remember, there are plenty of other girls who want this job.”

I stumbled out of Bill’s Gay Nineties and found my way to the subway and the sweet Chelsea apartment that had claimed all of our savings. Michael threw open the door, beer in hand, and swept me up in a ridiculously happy hug. “How was it? Is it great?”

“Yeah it’s really, ah, good.”

I tried desperately to think of something amusing or interesting that had happened, but all I could visualize was an image of that message spindle, with me impaled between pink paper slips. “Kathy — Miss Keeton — wasn’t there. I met some nice people. The guy who hired me took me out, I think I drank too much. I have to go to bed.”

All night I lay in bed like a plank of wood reliving the past two days and wondering what I had done wrong. That stupid outfit. I should have worn a business-like skirt and a white blouse with a peter pan collar, like the brunette I replaced. With a bra underneath! I had to go buy a bra. No. That wasn’t it. It was because my writing portfolio was full of nude photos from my Oui magazine gigs; Bernie Exeter must have thought I was coming on to him. Maybe it was something I said? I looked up at the ceiling, which was a few feet about my head, and tried to recall every word I had spoken to Bernie Exeter. I felt guilty and ashamed.

But I went back to the Viva office the next day, back to my little fishbowl. I had decided that when Bernie Exeter came by, twirling his mustachios and demanding his droit de seigneur, I would clutch my bosom and shout no, no, a thousand times no. I figured they’d have to pay me for two days anyway, and did long division on a scrap of paper to see how much that would be. At ten, Miss Keeton showed up and requested a cup of tea and a pack of Virginia Slims. At noon, Bernie Exeter appeared and glowered at me as I handed him the tower of magazine pages Miss Keeton had spent the morning marking up with red pen. At five, I checked the halls to see if the coast was clear and skedaddled home, where I lay awake a second night.

A few days passed. I tried to avoid Bernie Exeter. If I heard his voice in the corridor, I picked the phone and held a one-way conversation while scribbling “crap crap crap” on a message slip.

Somehow I still had a job. I met the other editors and the extremely well-dressed and desperate Viva advertising saleswomen, and a sweaty, unhappy circulation manager. Rowan Johnson, the drunken art director, introduced himself to me several times. I spent a few frantic minutes searching for Miss Keeton when Bob Guccione called, and then was mortified to finally find her in a stall in the ladies. I opened sticky letters from Joliet and waited for one long-winded dirty phone caller to run out of steam so I could say, “Thank you for calling!” and hang up. I reminded Miss Keeton of appointments with her hair dresser, dermatologist, astrologer, interior decorator, and jeweler. I fetched packs of Virginia Slims and made cups of tea. After Miss Keeton left for the day, I went into her office to remove and file every paper from her desk; she liked to start fresh every morning. I looked at that empty white desk and wished my mind were as blank.