The First Black U.S. Senator Argued for Integration after the Civil War

Despite a days-long outcry from Democratic senators attempting to block the first African-American member of the U.S. Congress from taking his seat, Hiram Rhodes Revels was finally voted in to the Senate along party lines 150 years ago today.

Revels had been appointed to his seat by Mississippi Republicans, as senators at the time were selected by the state legislature instead of by popular vote. Revels had served as an alderman in Natchez, Mississippi, having settled there after traveling the country as a minister, educator, and chaplain for the Union army. When he arrived in Washington, D.C. to be sworn in, Revels was met with protest from the minority Democrats.

“There was not an inch of standing or sitting room in the galleries, so densely were they packed,” according to The New York Times, “and to say that the interest was intense gives but a faint idea of the feeling which prevailed throughout the entire proceeding.” An atmosphere of fervent argument erupted in the chamber in those few days of deliberation over whether or not to allow the first black senator into the body, but the Times only hints at the insulting, racist language hurled at Revels and his defenders.

The official argument used against Revels was that he had not been a U.S. citizen for the nine years required to be eligible for the U.S. Senate. Even though Revels was born a free man — in 1827 — Democratic senators argued that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 had given the Mississippi alderman only four years of citizenship. Several Republicans held that this was an absurd argument, and that the Senate ought to vote Revels in and begin a new age of representation for African Americans. Democrats accused them of “hollowness and insincerity” for the causes of black men, claiming Republicans were only looking after “partisan considerations.”

In the late afternoon, on February 25th, the vote was taken, and Democrats lost, 48 yays to 8 nays. The Times credited Revels for remaining dignified even though “the abuse which had been poured upon him and on his race during the last two days might well have shaken the nerves of anyone.” He took an oath of office, took his seat, and the Senate was adjourned for the weekend.

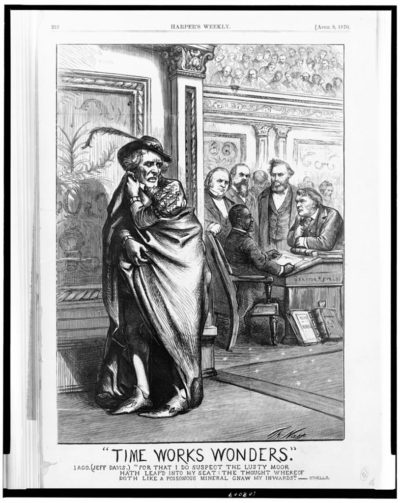

Of the two Mississippi Senate seats filled in that session, one had been most recently occupied by Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Harper’s Weekly ran a political cartoon by Thomas Nast that featured Davis as Iago, the traitorous villain of Shakespeare’s Othello, looking on at Revels taking his place in the chamber: “For that I do suspect the lusty moor hath leap’d into my seat: the thought whereof doth like a poisonous mineral gnaw my inwards.”

Revels only served in the U.S. Senate for about a year. Toward the end of his term, on February 8, 1871, Revels sat on the Committee on the District of Columbia as it heard arguments over a clause that would have effectively desegregated D.C. schools. Senator Revels addressed the committee, arguing against an amendment to strike the clause, saying, “If the nation should take a step for the encouragement of this prejudice against the colored race, can they have any ground upon which to predicate a hope that Heaven will smile upon them and prosper them?” He spoke about the oppression of African Americans all over the country that continued because of segregation in housing, church, transportation, and education, and he pleaded his fellow senators to consider how desegregated schools could help to empower African Americans “without one hair upon the head of any white man being harmed.” Unfortunately, his side lost the vote, and school segregation remained lawful in Washington, D.C. until 1954.

Revels was the first in a small wave of black southern congressmen during the Reconstruction Era. A few years after his term, another African American — Blanche Bruce — was elected to the Mississippi Senate. Bruce was able to serve a full term, but Mississippi hasn’t elected an African-American U.S. senator since. In fact, only ten have served in the history of the country.

Featured image: Hiram Revels, the first African American to serve as a U.S. senator. (Library of Congress / Brady Handy Photograph Collection)