Take an Epic Road Trip on the Lewis and Clark Trail

More than 200 years ago, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the Corps of Discovery, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, to explore the Louisiana Purchase and beyond. Journeying on the longest river in the present-day United States, Lewis and Clark’s team made their way across the continent to map the terrain, document wildlife, and establish relationships with native tribes. After a year and a half — and more than 4,000 miles — the Corps reached the Pacific Ocean.

Though the rivers and terrain traversed by the Corps of Discovery have changed over the years — for both natural and manmade reasons — you can still take a path comparable to theirs across the country. This year, the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail was extended to Pittsburgh to recognize the extensive preparations for the expedition that technically began near St. Louis. Traveling the 4,900 miles of the trail by car should take around a month, depending on how many of the hundreds of historical and natural stopovers you plan to include in your trip. The opportunity to encounter the complicated past of the country and its peoples firsthand is one that you’ll never forget.

St. Charles, Missouri

The Corps of Discovery reportedly bought all of the tobacco in St. Charles before venturing into the wilderness of the Louisiana Territory up the Missouri River. The Lewis and Clark Boathouse and Nature Center houses replicas of the keelboats that carried the team on their journey as well as interactive exhibits and a nature park. Nearby Frontier Park marks the spot where the Corps camped for five days, and — beginning there — you can bike 165 miles of Lewis and Clark’s route along the Missouri on the Katy Trail. If that seems like a lengthy trip, you can hike a mile or two of the trail instead.

Independence, Missouri

The hometown of President Harry S. Truman was also the place where Clark was separated from the party while hunting and found his way back by firing his rifle into the air. Independence is home to the National Frontier Trails Museum, where you can see artifacts and exhibits concerning the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe Trails as well as the Lewis and Clark Trail and the Mormon Pioneer Trail. About 14 miles outside of the city is Fort Osage, an outpost built under the direction of Clark after the expedition to defend the Louisiana Territory and trade with the Osage tribe.

The Loess Hills, Iowa

This region on the western edge of Iowa is known for its rolling hills and bluffs created by winds at the end of the last ice age. Visit the Waubonsie State Park, near Sidney, for trails and views of the Missouri River, and stop by the Mills County Historical Museum, in Glenwood, to see prehistoric Native American artifacts and a reproduction of a first-century earth lodge.

Pierre and Mobridge, South Dakota

The Corps of Discovery first encountered the Teton Sioux in Pierre. The Bad River Encounter Site marks the location of the council between the party and the tribe that almost turned deadly, and the downtown South Dakota Cultural Heritage Center offers interactive exhibits about early Native Americans and the settlers that followed. Further along the trail is Mobridge, a city across the river from the Standing Rock Reservation. The site of the now-destroyed Fort Manuel is where Sacagawea died six years after her journey with the Corps. Monuments to Sacagawea and Sitting Bull were erected on the reservation just across the river from Mobridge.

The Missouri Breaks, Montana

The Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument covers 149 miles of the river that took the Corps of Discovery three weeks to traverse. The badlands, cliffs, and plains of the area are largely unchanged since Lewis and Clark’s expedition and a must-see of any Lewis and Clark road trip. Be sure to visit the site where the Corps camped at Slaughter River — so named for their discovery of more than 100 dead buffalo — and the White Cliffs of the Missouri, where the Corps would have been shocked to see such geological splendor after spending time in “a country which presents little to our view, but scenes of bareness and desolation.”

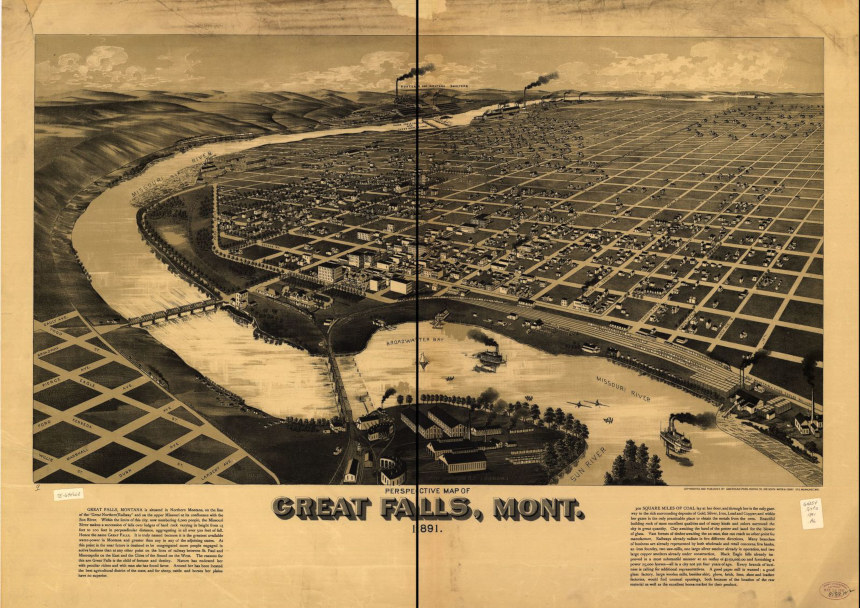

Great Falls, Montana

Lewis described the first of the five Great Falls as “a truly magnificent and sublimely grand object” when the Corps came upon the 400-foot waterfall in June of 1805. The group also took note of the freshwater springs now housed in Giant Springs State Park, which now feeds into a fish hatchery. Take advantage of the wildlife and breathtaking sights around this Montana hub, and visit during the Lewis and Clark Festival in June to enrich your historical adventure.

Salmon, Idaho

The Sacagawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center sits just outside the town of Salmon, where Sacagawea was born. The museum offers an outdoors experience of the Shoshone tribe to supplement the Lemhi County Historical Museum’s wealth of Lemhi Shoshone artifacts and exhibits. If you take a half-day to drive the Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road, the single-lane gravel road leads past several camps and sites along their trail. One of the most significant of these is Lemhi Pass, where the Corps stood and noticed “immense ranges of mountains still to the west” after thinking they were getting out of the Rockies.

The Dalles, Oregon

Clark estimated a village in the Columbia River Gorge to be drying 10,000 pounds of salmon when they passed through in 1805. The Corps traveled into the densely forested canyon from the arid desert of eastern Oregon, and — with breathtaking waterfalls, cliffs, and vistas — the area continues to be a land of plenty. The Dalles is the perfect place to learn and play, with the renowned Columbia Gorge Discovery Center giving an exhaustive history of the Gorge and places like Celilo Park offering spots for windsurfing and swimming.

Ilwaco, Washington

When the team reached the eastern end of Gray’s Bay, close to where the Columbia meets the Pacific, Clark wrote “Ocian in view! O! the joy” in his journal. As it turned out, they were still about 20 miles, and three weeks of storms, from sea. They reached the Pacific, eventually, in present-day Ilwaco, Washington. Cape Disappointment’s Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center offers a history lesson on the Corps’ journey against the backdrop of an 1856 lighthouse and the pounding surf of the Pacific.

Astoria, Oregon

Although the Corps of Discovery first met with the ocean in present-day Washington, the party took a vote that decided they would stay for the winter across the Columbia river in what is now Astoria, Oregon. They built Fort Clatsop and stayed from December 1805 to March 1806 — during which there were only six days without rain. The Lewis and Clark National Historical Park gives guided canoe tours, reenactments, and a replica of the original fort where the Corps spent their miserable winter thousands of miles from home.

Featured image: Ericshawwhite, Wikimedia Commons, via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

Taken For A Ride: Around the Midwest on a Triumph Bonneville

In an earlier issue (May/June 2018), I mentioned I would be taking a solo motorcycle trip south along the Mississippi River on my 1974 Triumph Bonneville. Several Post readers wrote asking if they could join me, one of whom was a woman wanting to know whether I was married and if I might like a little company. Apparently, there is nothing like a motorcycle trip to excite the imagination.

I’m pleased to report the trip was a success, though it went nothing like I had planned. When Rod Collester, my friend and a vintage Triumph expert, learned my intentions, he advised me not to ride a 44-year-old motorcycle with an oil leak rivaling the Exxon Valdez halfway across the country. Fortunately, I also own a new Triumph Bonneville that from a hundred yards away looks a lot like my old Triumph Bonneville, which, as we say in Indiana, is close enough for government work, so I rode it instead.

Then two friends, Ned and Mike, heard of my trip and asked if they could come along, and I said yes, even though they ride a Honda and a Harley Davidson. While I never hold someone’s gender, religion, race, national origin, or sexual orientation against them, I have been known to look down my nose at people with so little regard for Triumph motorcycles that they would ride something else. But I swallowed my pride and invited them to join me, provided they refrain from making snide comments about the size of my motorcycle (900cc) compared to theirs (1300 and 1800 ccs). They kept their word for the first hundred miles, and then Ned referred to my bike as a “moped” and Mike laughed so hard he snotted himself.

By some quirk of fate, we left on our trip the same day the tropical cyclone Alberto hit landfall in the Gulf Coast, spawning storms and record rainfall along our intended route. Instead of heading south, we rode northwest 350 miles to Galena, Illinois, where Ulysses S. Grant was living when the Civil War broke out, working as a clerk at his father’s store, a job he despised but took because he was broke. If you ever feel like giving up, it might help to remember that in 1857, Grant pawned his watch to buy Christmas gifts for his family, then 10 years later was a national hero, well on his way to the presidency. (Grant was so virtuous, I can’t help but think that if the motorcycle had been invented then, he would have ridden a Triumph Bonneville.) We spent the night at the DeSoto House Hotel, built in 1855 and named after Hernando De Soto, who was purported to have discovered the Mississippi River on May 8, 1541, much to the surprise of the Native Americans who were already there, many of whom he promptly killed.

In Olney, a storm struck from the northwest, and I prayed it would give birth to a tornado and kill me dead.

The next morning, dodging Alberto’s offspring, we rode south along the Great River Road to Fort Madison, Iowa. If you’ve ever eaten Armour bacon, then in a roundabout way you’ve visited Fort Madison, too, since their processing plant is southwest of town along Highway 61. The scent of meat hangs over the place, a not altogether unpleasant aroma. Every town should be so fortunate to smell like bacon. We stayed the night in a Super 8 motel owned by a man from India who, though unintelligible, was thoroughly helpful. I’m not sure why so many Indians own hotels in America, and I don’t care so long as the rooms are clean and they have a TV channel that shows The Andy Griffith Show and Gunsmoke.

The next day found us in Hannibal, Missouri, the hometown of Mark Twain, which we would never have figured out except for the Mark Twain Hotel, the Mark Twain Restaurant, the Mark Twain Cave, the Mark Twain Antique Shop, the Mark Twain Museum, Mark Twain Avenue, the Mark Twain Boyhood Home, the Mark Twain Memorial Lighthouse, and the Mark Twain Brewing Company, where Mike, against our advice, danced on a table. Continuing southward, we eventually crossed the Mississippi on the Golden Eagle ferry, motored seven pleasant miles across the Brussels peninsula, ferried across the Illinois River, and stayed the night at the Pere Marquette State Park Lodge, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. The next time someone tells you the government can’t do anything right, take them to the Pere Marquette State Park Lodge six miles west of Grafton, Illinois, and show them what America did when it had intelligent and visionary leaders.

If on the Judgment Day I am sentenced to hell, I will appeal the verdict by pointing out that I have already been there, on U.S. 50 crossing Illinois from Lebanon to Lawrenceville, an unrelentingly boring stretch of road 119 miles in length that felt like a thousand. In Olney, a storm struck from the northwest, and I prayed it would give birth to a tornado and kill me dead. Alas, I was not so fortunate and entered Indiana at Vincennes, the hometown of my parents and, coincidentally, Ned’s residence while serving as a district superintendent for the United Methodist Church during his years of checkered employment. I asked Ned if he wanted to go off the bypass and ride through town and he said “God, no,” or something to that effect. I could only conclude that when he left Vincennes, he had been asked never to return.

We continued east on U.S. 50 through Amish country down to French Lick, hometown of basketball legend Larry Bird, where we stopped for dinner at the West Baden Hotel and ate grilled cheese sandwiches, the only thing on the menu we could afford. From there, we rode through the countryside to our farmhouse in Young’s Creek, built by my wife’s grandfather, Linus Apple, in 1913 and restored 98 years later by my wife and me before I spent all our money on motorcycles.

The next day found us heading north toward home, a formerly bucolic drive until Indiana’s governor, three governors ago, had the bright idea to turn a perfectly good state highway into an interstate, transforming a two-hour jaunt into a four-hour Sisyphean slog. I rolled into our garage five days and 1,123 miles after our departure and remain, to this day, a jaded and weary man, worn down by the road and my association with two dubious characters. Next year, I am informed, we will tackle the Natchez Trace Parkway through Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. I can hardly wait.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and author of 22 books, including the Harmony and Hope series featuring Sam Gardner.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.