How America Learned to Love Modern Art

“Horrible.”

“Shameful.”

“Obscene.”

When the early impressionists began exhibiting their works in the 1800s, the art critics of Europe couldn’t find enough words to attack their paintings. “Shocking.” “Degenerate.” “Works of idleness and impotent stupidity.”

The public could be just as critical. A visitor to an exhibit of Matisse and Picasso works gave a typical verdict: “Godalmighty rubbish.”

Had those long-ago critics controlled public opinion, modern art would have died in its infancy. Today, painters would be competing with photographers to produce pictures in life-like detail.

But modern art survived and eventually earned general acceptance. Today, we barely notice the cubist still-life hanging in a bank lobby or the enormous abstract painting in a restaurant. Furthermore, the works of Van Gogh and Monet, so loudly condemned in their day, are among the most popular paintings in the world. In 1990, Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet sold for $82.5 million, making it one of the world’s most expensive paintings.

How did modern art survive and gain a popular following, despite the hostile reception that critics and the public gave it?

According to a classic article in the Post (“The House that Art Built,” January 1965), much of the credit goes to The Museum of Modern Art, or MoMA. The then-revolutionary museum opened on November 7, 1929, barely a week after the great stock market crash. Its first exhibit contained paintings by Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Seurat, drawn from the collections of three women. For one of them, art collector Lillie P. Bliss, the exhibit was a chance to bring her Picassos out of the attic, since her mother had forbidden her to hang them in their house.

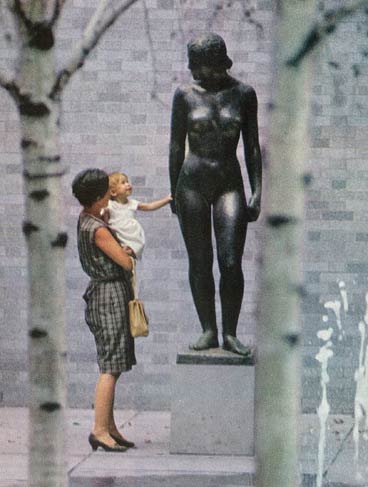

Visitors were enticed to the museum by its innovative and unpredictable exhibits. They also appreciated its informal atmosphere, and the fact that the museum didn’t take itself too seriously. After all, the museum’s director admitted, not all the works on display could be masterpieces. The museum would be lucky, he said, if one-twelfth of its paintings kept their value for 20 years.

Still, the new museum proved surprisingly popular with the public. The growing crowds at exhibits forced the museum to keep moving into larger galleries. Ultimately it came to rest in a Manhattan building that a 1947 Post article (“The Museum and the Redhead,” April 1947) described as “a fancy, six-story jack-in-the-box that is continually popping out with something new and remarkable.”

The MoMA also helped create the city’s booming market in contemporary art. The Post reported that, between 1930 and 1965, the number of New York galleries dedicated to contemporary art had grown from less than a dozen to 400.

Many visitors were still baffled and challenged by the museum’s experimental works from such artists as Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol. But even if they didn’t understand it, they seemed to accept modern art as significant. Americans’ opinions about new art were changing, said a museum lecturer told the Post. He could tell because people used to tell him that a 5-year-old could paint as well as the artists whose works hung in the museum. “Now, it’s gone up to 7- or 8-year-olds.”

But one museum, alone, couldn’t have lead to Americans’ growing acceptance of modern art. A larger influence was at work in the U.S., as Brenda Ueland observed in her 1930 article “Art, Or You Don’t Know What You Like.” (Continued on page 2.)

Learning Art from Advertising

Published just a few months after the MoMA opened, “Art, Or You Don’t Know What You Like” is still a well-written introduction to modern art.

In it, Ueland claimed that Americans were developing a taste for more abstract, expressive art because of advertising. Modern retailers were using contemporary art styles in their print advertising, and the ubiquity of these styles had slowly worn off the shock value.

The trend had begun before World War I, she said, when Parisian designers had hired young artists to illustrate their new fashions. Soon, manufacturers and retailers were copying the new style in their ads. As the writer explains:

“American fashion magazines … had formerly been lugubrious dressmakers’ manuals, full of … (old-fashioned) pictures of wasp-waisted ladies carrying parasols. (Now) fashion artists became sophisticated—modern. Not that there was anything particularly artistically valuable because ladies’ necks were now drawn two feet long and their slippered feet became two-pronged forks. But there was respect at last for originality and freedom.

“The artists began to get some real money for it. The movement spread from fashions to—automobiles, cigarettes, glass, silver, radios, grand pianos, furniture, bathrooms, and so on.”

The retail industry saw modern art as a way to give their products an up-to-date feel. They believed consumers would associate avant-garde design in advertisements with sophistication, youth, and innovation, whether the product was an automobile or a furniture polish.

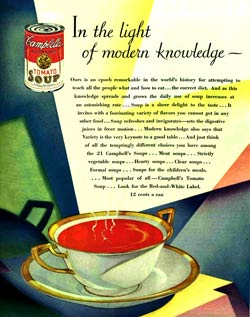

Over the years, magazine readers received a continuing education in the changing schools of art as advertising experimented with symbolism, modernism, art deco, and abstract art. The connection between modern art and advertising was so well established that Americans were less startled by Andy Warhol’s soup can art than art critics were. After all, we had learned to regard an advertisement as both a sales pitch and an artistic statement.

Advertising Follows Art Trends

The ads below, all from the Post, reflect the influence of modern art in advertising. The first group shows the limits imposed by a traditional style of illustration. The second group, all taken from the issue that included Ueland’s “Art, Or You Don’t Know What You Like” article, show how modernism affected the colors, illustration style, and layout in advertisements.

Early 1900s—Ads Trapped in Realism

1930s—Ads Show Influence of Modern Art