The Case for Saving Endangered Species: 1964 and Today

Since the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620, more than 500 species and varieties of animals and plants on our continent have become extinct, including the California golden bear, the eastern cougar, and the Tacoma pocket gopher.

Conservationists have been working for generations to preserve species that are precariously close to joining those 500. They’ve been helped by the Endangered Species Preservation Acts of 1966, 1969, and 1973.

These laws, supported by conservationists, naturalists, and hunters, have saved several species of wildlife, including alligators, bald eagles, peregrine falcons, wolves, grizzly bears, and California condors.

The whooping crane, for example, came dangerously close to extinction. In his 1967 article, “A Close Look at Wildlife in America,” Bil Gilbert reported that only 43 whooping cranes remained. Today, with protective measures, the population has risen to 603. But with their wetlands disappearing beneath developments, the whooping cranes’ longevity still isn’t assured.

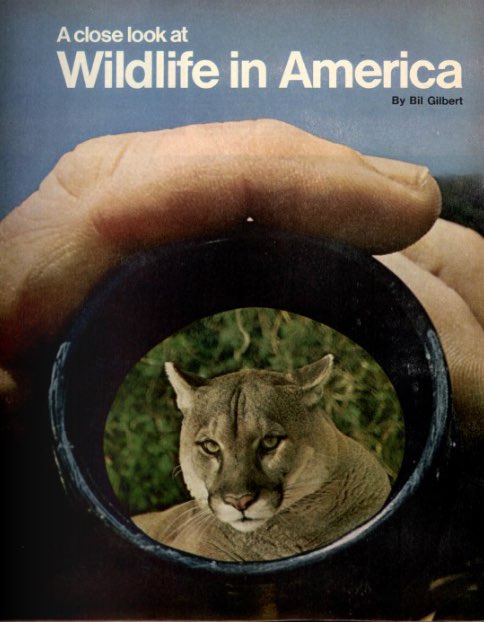

In 1967, Gilbert’s ideas about ecological damage would have been unfamiliar to many. In his article, he tried to make a solid case for the importance, and the complexity, of conserving wildlife and preserving an ecological balance.

Then, as now, some Americans wonder why saving species is important apart from keeping bird watchers, wildlife lovers, and hunters happy. Here are four:

- Preserving natural diversity. With every species that disappears, the environment loses a little more of the reserves it needs to respond to natural or man-made disasters. As the monarch butterfly population drops sharply because of overuse of herbicide, so does the population of birds that feed on the monarch larvae, which, in turn, alters the fertilization patterns of the plants that feed any number of other animal species, including us Homo sapiens. If monarch butterfly populations fall off, remaining butterfly species can’t make up for the missing link in the food chain.

- Contributing to medicine. Tarantula venom is now being tested as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Taxol, now the standard treatment for ovarian cancer, is based on a molecule so complex that researchers might never have developed it. It was discovered in a weed tree, the Pacific yew, which was routinely discarded in logging operations.

- Monitoring health risk. In 1913 , miners began bringing canaries into the mines with them because the birds would register the presence of poisonous gases before the miners. Today, honeybees are used to monitor air quality, mollusks for water quality, and swallows, bats, and fish for rising presence of pesticides in the environment. A sharp decline in a species could signal a rising danger to humans.

- Boosting the economy. Wolf tourism in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho brings over $35 million in revenues to those states. When bird watchers come to Texas each year, they pump $400 million into the state economy.

We can’t count on the natural world to adjust itself to the vagaries of human progress, or on human ingenuity to develop a miraculous, last-minute solution when extinction starts hitting home. Ultimately, the species we’re trying to save is our own.

Featured image: American Elk (John James Audubon, Brooklyn Museum)