Selling Cars to Women in the 1930s

John LaGatta

January 6, 1934

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

In 1914, the Curtis Publishing Company, parent corporation of the Post, had commissioned a study of the automobile market. Designed to help its sales force understand and capture a booming new market, it also provides today valuable insight into the thinking of the time. A follow-up study was published in 1932. The following selection from that later report documented the fact that women were not just influencing car-buying decisions but actually buying and driving cars. The modern reader may hold her nose at the presumptions made about female character, taste, and (implicitly) intelligence, but for the same reasons, this excerpt is a fascinating look, not just at car buying trends, but at gender roles and stereotypes of the 1930s.

Our 1914 marketing report said: “Whatever is bought for family use is selected largely by the wife, and the automobile is no exception. Dealers’ estimates of the proportion of sales of pleasure cars in which women are an important factor vary from 50 percent to 95 percent.” But, few women owned or drove cars in 1914. Cars were still heavy and hard-steering. Cars used by women were mostly chauffeur driven. For a woman to take a car to a service station was so unusual as to seem out of place. Driving was a novelty and a hardship; it had yet to become a matter-of-fact occurrence in woman’s everyday life.

Today, not only are women in the family the determining influence in the purchase of a car, they are at the wheel, weaving confidently through crowded traffic, driving at express-train speed along the highways, parking with the dexterity of experts, shifting gears noiselessly, and steering with one-finger control.

What has changed? Let’s begin with the self-starter, which gave the first great impetus to women’s use of the motor car. Prior to this time, the car had to be cranked by hand. Whether they would admit it or not, women were afraid of the motor car, and fear with inconvenience, discomfort, and physical inaptitude were only to give way gradually before self-starters, electric lights, cord tires, closed bodies, four-wheel brakes, easier steering, shock absorbers, and easier shifting.

Fear of the Breakdown

Good as motor cars were in 1914, there were still two bugaboos that held back the woman’s market. One was mechanical trouble and the other was tire trouble. Cars still were subject to tantrums on the road, carburetor trouble, spark plug and other ignition trouble, broken springs, leaky radiators, and a host of minor annoyances. To the dyed-in-the-wool motor car fan, these difficulties were interesting challenges to mechanical resourcefulness; to the woman they were fatal to any hope she might have to own or drive her own car. On the road mechanical trouble rendered a woman helpless. She was under obligations to the first Good Samaritan motorist passing by or at the mercy of the nearest repairman.

So, too, with tires. Jacks, rims, patches, tire cement, tire talcum, tire pumps, and tire irons were out of her line. Today with tires that frequently run over 30,000 miles without trouble, it is difficult to realize that 3,000 miles was a lot of service for some tires in the early days. With each improvement mechanically, more and more women were attracted to the utility and pleasures of car use and ownership.

Financing

With the introduction of time payments, car sales involving the woman gained new impetus. Until then sales were for cash only. To the woman who consciously or not budgeted the family expenditures, hundreds of dollars could not be spent all at one time for a motor car. It meant drawing on the family savings, or even mortgaging the home. It was beyond most women’s comprehension. Responsible for the family expenditures, women instinctively opposed so great an investment.

Broken up, however, into relatively small monthly payments, with a relatively small payment down, the purchase of a car assumed reasonable proportions. It came within the family’s ability for fulfillment without hardship. Women again came to the aid of an industry approaching “saturation.”

Closed Cars

Meanwhile another important factor had been at work. Seventy percent of all cars produced in 1922 had been open models. Good as these open models had been, certain of their features were objectionable to women. They were cold and drafty. Curtains sometimes leaked. If tops were lowered, they had to be raised — a man’s work. Side curtains had to be furled and unfurled, snapped into place and unsnapped, stored away in the summer and brought out in the winter. Their composition windows cracked and scratched easily, became opaque and made for poor visibility.

In 1922, the Fisher Body Corporation started advertising closed bodies nationally. In 1923 the Hudson Motor Car Company announced a closed coach which sold for $5 less than the corresponding open model. This small seed was to bear great fruit. But at first the obstacle was cost. The difference between the cost of a Dodge 1921 Model Touring Car and a Dodge 1921 (closed) Sedan was $865. Few women could see the desirability of paying $865 more for the same car with a little different body on it just to be comfortable. Thus, the high price of early closed cars impeded the growth of the industry and shut out a waiting multitude of year-round women drivers.

Once prices came down, that unloosed the floodgates of buying. Vast new markets opened up. A car which the whole family could use and enjoy winter or summer became its own justification. Women’s support in car purchase could be depended upon increasingly.

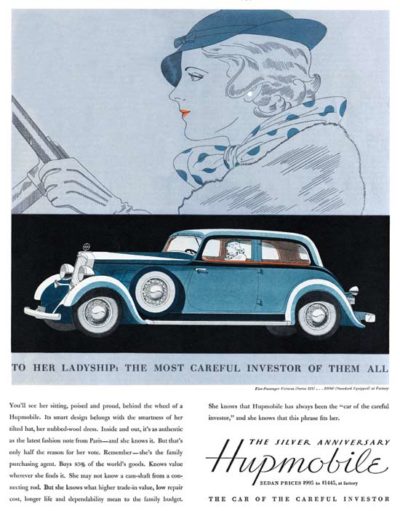

Of no little importance in this development were the means by which women’s interest was intrigued by advertising. Car advertising featured fine-looking modishly gowned women at the wheel. In upholstery, finish, body hardware, flower vases, vanity cases, floor coverings, and instrument hoards, body designers got away from the utilitarian and went feminine. In effect, the motor car became a drawing-room on wheels. By 1931, 92.2 percent of all cars were closed.

Color and Design

With lacquer finish it was easier to keep cars looking well. Many retained a bright and shining newness for years instead of months. The dull appearing car, to which women were more sensitive than men, was passing. Car manufacturers, meanwhile, were giving their cars better lines. Lines, color harmony, upholstery, body hardware — this was a language a woman understood.

Important as eye appeal became in attracting the favor of the woman, mechanical improvements of value in exploiting this market were not overlooked. Shorter wheel bases and easier steering that overcame woman’s difficulty in parking came in 1924, as did balloon tires with greater safety and riding comfort. Four-wheel brakes overcame the fear many women had of not being able to stop. Automatic windshield wipers that relieved her of the necessity of taking one hand off the wheel as was required by the hand operated wiper, car heaters that maintained room temperature in below zero weather, shock absorbers as regular equipment — all contributed toward increased momentum of sales to women.

Better Roads

The fear that many women drivers had of traffic and cross streets passed with easier handling cars and better traffic

control. Widened streets and roads, stop lights, stop streets, one-way streets and highways, under and over passes, and standardized traffic regulations — all these factors contributed toward making driving by women easier and more pleasurable.

Throughout all this period the building of good roads had been removing one more handicap to increased use and ownership of cars by women. In 1914, and long after, road trouble was accepted as part of the game. Tow rope, shovel, and tire chains were still necessary touring equipment. Extricating a car that was stuck in the mud or sand or that had skidded into a ditch was no work for women. Today all that is changed. A woman can drive from Michigan to Florida on an uninterrupted ribbon of paved road over 1,000 miles long. She can drive almost anywhere in the United States or Canada on roads that may be better paved than the streets in her own home city.

Skidding Reduced

Between 1914 and 1932 one of the drawbacks to increasing use and ownership of cars by women was fear of skidding. Muddy, gravelly, and slippery roads; two-wheel brakes; car weight and high center of gravity; hard steering — all contributed to this problem. It took an expert driver to pull himself out of a skid. It required strength of arm as well as quickness of action. The feeling of utter helplessness that came from a skidding car spoiled many a promising woman motorist.

With safe roads, better balanced cars with lower centers of gravity, easy operating four-wheel brakes, low-pressure tires, and easier steering, the skid largely disappeared as a menace to increased women’s use.

Easier Gear Shifting

In learning to drive a car, and in operating it afterward, many women were inclined to have some trouble with the clutch and the gear shift. Here, again, a certain knack was needed. By nature not mechanically inclined and often with no very clear idea as to exactly what these mysterious operations were all about, more women than one gave up the desire to drive at the first lesson. In 1928 easier gear shifting was introduced by Cadillac and LaSalle. Today syncro-mesh, syncro-shift, or some other form of easy gear shift is regular equipment even on low-price cars. At last here was a shift that any woman, no matter how great a novice, could operate without clashing. Another appreciated improvement that met with women’s favor had been made.

Less Noise

Another gradual improvement of considerable influence was due to increasing quietness. Grinding and clashing gears, racing and knocking motors, squealing brakes, squeaking bodies, springs, and shackles were enough to annoy, if not to unnerve, any one inclined to fear that any unfamiliar noise meant the car that cost so much money was being ruined. The fuel knock that sounded as if the car were pounding itself to pieces began to disappear in 1923 with introduction of anti-knock gasoline. Cars that run today almost as quietly as a sewing machine have everlastingly removed that barrier to woman’s use.

Her Car — A Woman’s Necessity

While from 1914 to 1931 we believe that the woman was most important as a passenger and of great influence in directing motor car purchase, from 1932 on it is our belief that her presence to the industry will be most felt as an increasing user of motor cars. In our consumer survey, women were reported as driving in 54.4 percent of the homes interviewed. The motor car today is woman’s mark of social standing.

In conclusion, between 1914 and 1931, with each new improvement in construction, that made woman’s use safer, more comfortable, or more convenient, great numbers enlisted in the ranks of women car owners and drivers. Women handle cars today easily, expertly, and fearlessly. Nervous tension has given way to relaxation and real motoring enjoyment. The road to the woman’s market at last is wide open.

—“Increasing Ownership and Use of Motor Cars by Women,”

The Passenger Car Industry, 1932