North Country Girl: Chapter 7 — We Have Ice Cream in the Fridge

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

TV, board games and toys, and school were indoor activities. But year-round, with the exception of raging blizzards, my mother ordered me to put down my book and go “play outside.” We had enough kids on Lakeview and Vermillion for a good game of Spud (very few cars went down our single-block-long street) or freeze tag. I had a particular fondness for “Mother May I;” little prig that I was, I delighted in sending kids back who forgot to ask permission. “Red Light, Green Light” was too prone to cheating, and always ended up as “I saw you move!” (a lie) countered by “I didn’t move!” (another lie). Once a summer, the ice cream truck magically found its way to our block to interrupt our street games, and I would lose my mind with desire for a Nutty Buddy only to by informed by my mother that if I wanted ice cream we had some in the fridge.

My mom was stingy with treats, doling them out occasionally and always one at a time. Each year we went to the Norshor theater to see the annual Disney feature, missing only “Bon Voyage” as it was condemned by the Catholic church for having a scene where the harried American dad is accosted by a Parisian hooker. Going to the movies was treat enough. Getting popcorn or Junior Mints from the snack bar would be gilding the lily.

It was the same at the Northland Country Club pool. Once in a great while I would be allowed to buy a frozen Snickers or Milky Way at the snack bar, at the exorbitant price of fifteen cents, five cents more than the going rate. Mostly we arrived at the pool after lunch and were forced to exist on grapes from home. But once or twice a summer my mom, my sister Lani, and I would sit up on Northland’s gracious veranda, looking out over the pool and first tee, and order divine hamburgers and golden French fries with brown crispy ends. I would slather everything on my plate with ketchup; Lani would leave most of her food for my mom and I to finish up. I later found out that my mom was afraid my dad would be mad about her minor country club charges; he was too busy losing hundreds of dollars in the never-ending Northland poker game to even notice our once a month lunches on the bill.

We were allowed hot chocolate when skiing at tiny Mount du Lac, but that bordered on a life saving measure when we came out of the zero degree cold with soggy wool mittens and frozen-over ski boot laces. The Mount du Lac “chalet” was a squat square concrete building, with window seats overlooking the three ski slopes (beginner, with the jerky tow rope that yanked me forward, landing face in the snow; intermediate, with the impossible to balance T-bar that dumped me on my back; and advanced, where I never managed to set ski on). The chalet had a jukebox and a pinball table, both of which I was dying to play (probably to postpone my return outside). Putting a dime in either of these machines was regarded by my mom as the height of wastefulness. When I finally got to play pinball, with my own dime, I was astonished at how quickly and surely the silver balls tumbled to the bottom and down the hole, failing to set off even a single bell of pinball success.

Why anyone would put money in a jukebox baffled my mother. “You can hear the same songs for free on the radio!” Pinball was even worse in her eyes: not only did you throw away a dime that could have bought an ice cream cone, candy bar, or bottle of pop, your brain cells curled up and died when you played such a stupid game.

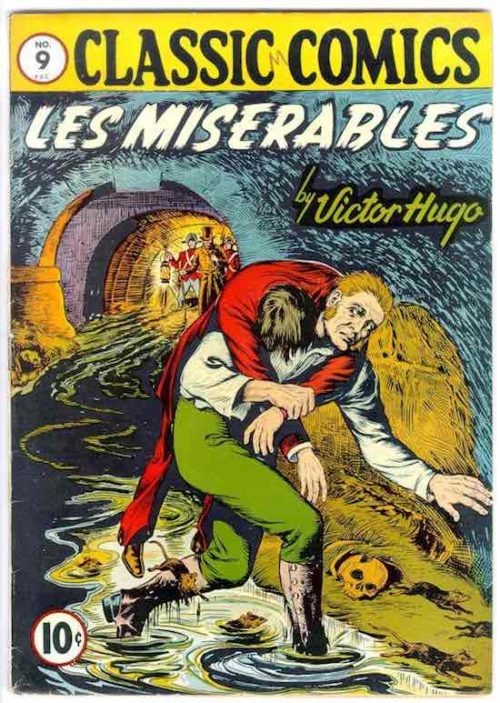

Since all my mother’s efforts to transform me into the outgoing, cute, popular girl that she had been had failed, my mother turned her attention to protecting and improving my one asset, my smarts. She regarded comic books (except for the tedious Classics Illustrated) and Mad magazine as insidious destroyers of children’s intelligence: “If you read comics it will make you so stupid you won’t be able to read anything else.” I couldn’t get enough of that forbidden fruit. A neighbor girl stopped asking me over to play because I could not be budged from her older brother’s breathtaking collection of Mad magazines.

My preferred reading was definitely lowbrow, but I would read anything. When I ran out of library books, I resorted to our World Book Encyclopedia, or the lavishly and gorily illustrated children’s bible (heavy on the Old Testament) that somehow washed up on our living room bookshelf. There were also a few ancient children’s books that I read over and over: The Story of Live Dolls, The King of the Golden River, The Five Little Peppers, and Alice’s adventures both in Wonderland and through the Looking Glass. Eventually my mother realized that I was not to be bullied off of the couch and into the clique of popular Congdon Elementary girls. If I was going to have my nose in a book every waking hour, it should be a book that would improve my mind.

One glorious day I came home from school and found a brown box from the Classics Book Club addressed to me. Getting anything in the mail with your name on it was thrilling. I had long pleaded for my own subscription to Highlights for Children just for that reason, but that was not going to happen while my father could bring home the torn, scribbled-on old Highlights from his office. Inside this book-shaped box was a book, Shakespeare’s Comedies, the plays printed in mouse type on tissue thin paper nicely bound in gilded imitation leather. I started right in on The Tempest, reading the Miranda part out loud and understanding maybe a tenth of what was going on.

The next month brought the Tragedies. I had figured out how to skip the boring parts of the plays, which were everything except the lead female role: I dragged my finger down the page until I found lines for Juliet and Cleopatra and Ophelia, which I declaimed aloud from my sofa stage. The following month the Histories arrived which I barely cracked. Henry, Henry, Henry. Where were the good female roles?

Then came the dunning letters. Which were also addressed to me. My mother had thoughtfully put the subscription to the Classic Book Club in my name, but she had never bothered to pay for it. According to them, I owed $36.00 and my membership would be revoked and I would never receive the next book in the series — Plato’s Republic— unless they received payment in ten days. Where was I going to get the astounding sum of $36? I went to my mother in tears. She looked at the letter, crumpled it up, and tossed it in the garbage. Even more than she hated wasting money, my mother loved getting something for nothing; we had the books already, so why pay for them? But the letters kept coming, informing Miss Gay Haubner that the Classics Book Club was about to take legal action to recoup their money. For months, I expected someone to show up at the door and arrest me.