Ogden Nash on the Car as Rite of Passage

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

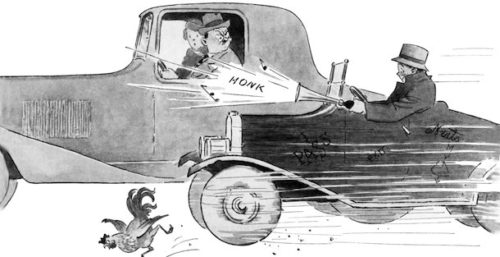

In this charming 1934 essay, the great American poet and humorist treats on the “in-between” generation — those who grew up while the horse and buggy was giving way to the automobile, and trusting in neither.

Psychiatrists differ among themselves as to just what is the most important step in the progress of the human male toward the complete life. They differ noisily, they differ bitterly, pausing occasionally to split the profits resulting from the argument, then resuming anew, as psychiatrists will. “The first kiss,” says Vienna. “The first shaving lotion,” says Berlin. “The first tail coat,” says London. New York holds out for the first weekly salary check, while Baltimore meekly suggests that the first approach of paternity may mean a lot.

The only conclusion to be drawn from this futile bickering is that psychiatry is not only in its infancy, as the doctors themselves admit, but lingers in the halcyon days before horseless carriages, when people could think of no better ways to pass the time than osculation, self-adornment, self-support, and matrimony. Lurking in the furthermost leather recesses of their secluded and luxurious consulting rooms, lost in morbid contemplation of the horrific and scandalous details that fill their case books, psychiatrists have failed to remark a fact now so well established as to be obvious to any mind but their own — that modern man begins to live life to the utmost only after he has driven his first car its first 1,000 miles. Take the case of Mr. Migg.

Mr. Migg belongs to the unhappy generation that was psychologically squashed between the tailboard of the buggy and the acetylene headlights of the Pope Toledo. Children born five years earlier than he, arrived with a curry comb in one hand and a bridle in the other; five years later, they wore goggles and were equipped with drivers’ licenses. To this in-between generation belongs the doubtful privilege of instinctively distrusting both the horse and the automobile.

People proud of their modernity spoke rudely of horses during Mr. Migg’s childhood; they wondered how they had ever put up with horses; their skittishness, their viciousness, their sloth, their undependability; Mr. Migg received the ineradicable impression that a horse was a combination of tapeworm, tiger, and tornado. He was definitely off horses. Once in his youth he gave a horse an apple because a girl asked him to and stood over him till he did it. He thinks it was the bravest act of his life, for he expected to lose his arm at the elbow. True, he still has his arm, but only, he is convinced, because that horse at that moment was gorged with elbows.

On the other hand, the very people who were selling their horses down the river, trading in their whips for monkey wrenches, and turning their stables into garages, planted in Mr. Migg’s mind a leeriness of automobiles which it has taken many years to uproot. The conversation of the pioneer motorist was prideful, but it reeked of disaster. It seemed to Mr. Migg that automobiles were always breaking down or blowing up. If he had to go from one place to another, he thought, give him the good old choo-choos every time.

Years passed. Automotive engineers spent thousands of sleepless nights figuring out ways to make life easier for the motorist. Finally one automotive engineer said to another automotive engineer, “I’ve got it;” and the other automotive engineer said, “What?” and the first automotive engineer said, “Let’s fix it so the motorist can motor sitting down.” Everybody thought that was a splendid idea and wondered why no one had ever thought of it before. The first step was to move the gasoline tank out from under the front seat. There was some stiff opposition to this move, as many people complained that getting out and lifting up the front seat every 10 gallons or so gave them a needed opportunity to recover hairpins, love letters, odd change, latch keys, and other small objects which they had been wondering where they were for days. Public reaction, on the whole, however, was favorable, and the automotive engineers went ahead. Lights, for example. It used to take two people to turn the lights on. One to stand twisting the jigger on the acetylene tank on the running board, and another to stand with a lighted match by the headlights. It could be done by one man, but he had to be exceptionally fast on his feet. If he took too long to cover the ground between the tank and the headlights, he was likely to be blown into the livery stable when he applied the match. This elaborate process finally struck some automotive engineer as being highly inconvenient. He was probably a slow-moving man with sore feet; at any rate, he succeeded in correcting it, and the rest of us can now turn on the lights without first stopping the car.

The designers were overcoming Mr. Migg’s prejudices one by one. When they fixed it so that you could start the engine without going out front and winding it up, he succumbed. He even speculated timidly on the possibility of some day learning to drive. It took several years for this idea to blossom, but eventually, on entering college, he borrowed his roommate’s car, somehow passed a Massachusetts driver’s test, and three hours later, turning out to avoid a truck, drove rapidly into the side of the Odd Fellows’ Hall in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. He left his roommate to cope with the Odd Fellows and took a train back to Boston.

The next time he straddled a steering rod was, as in the episode of the horse and the apple, at the instigation of a lady. She would like to go for a drive in the country, she said. Mr. Migg could think of no one who would not be better off for a drive in the country, and he said so. It was only then that he discovered that the lady did not drive. She could, she said, get her brother to drive, if Mr. Migg wouldn’t mind sitting in the backseat. Mr. Migg said he loved driving. They set off in a stream of traffic that failed to diminish as they left the city limits behind. Nevertheless, all went swimmingly till, halfway up a steep hill, the lady decided that she liked the looks of a little road leading off to the left. Chivalrous as always, Mr. Migg stuck out his hand, racked the gears to shreds, stalled the motor, and coasted backwards to the foot of the hill through a shrieking maze of infuriated 10-ton trucks. “I guess you’re not used to this car,” she said kindly. Mr. Migg agreed, and started up the hill again. After a few more failed attempts, she said she thought she remembered hearing that there were bandits or wild dogs or something along that road to the left and she’d just as soon go straight home.

He passed the next few years pleasantly in qualifying for a driver’s license in New York State. He finally obtained it, and almost immediately found himself the head of a family three states away. Cause and result? Mr. Migg hesitates to say. He only knows that he found that he and his wife would have to get a car, and get one immediate.

Once having bought his own car, he could think of nothing else but getting those first 1,000 miles under his belt. Mr. Migg begs for errands to drive. He drives to the mail box and the drug store and the grocery store, none of them farther distant from the house than a clean three-base hit, and he wishes he could drive from the living room into the dining room. When you’re trying to cover 1,000 miles at 27 miles an hour every inch counts. If the Miggs have the choice of several movies, they go not to the best but to the farthest. Old ladies far out in the country whom they haven’t seen in years are being surprised every day by little visits from the Miggs. They never lose a chance to take people home from parties, particularly if they live well out of the way. They are getting quite a reputation for being friendly and obliging.

Mr. Migg still winces when he has to pull over to let a homemade sports roadster go by. But he checked the mileage this morning. Only 57 more to go. Only 57 miles from manhood. He notices that the speedometer registers up to 95.

—“The First Thousand Miles,”

The Saturday Evening Post, February 24, 1934