North Country Girl: Chapter 32 — Bamboozled at East High

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

As if we were still in elementary school, we teenagers delighted in anything that was a disruption in the school day. One poor kid, not the brightest light in the harbor, made a series of phone calls to the East office, claiming he had placed a bomb in the school, freeing the rest of us outdoors into the grey chill of a Duluth spring, no time to fetch coats or mittens from our lockers. Standing where somebody decided was a safe enough distance from a bomb, we kept warm by huddling in our little cliques, reveling over being sprung from chemistry or French II or metal shop.

Since the fake-bomb-threat miscreant had been spotted at the school’s one and only pay phone immediately before each evacuation, we all knew who he was, but our lips were sealed. The last time he called in a bomb threat, he must have been unhinged by the many thumbs up shot his way by passing students; he stuttered out to the school secretary, “And this isn’t (miscreant’s name)!” We never saw him after that.

Assemblies also broke up the school day; unlike the thunderous pep rallies held in the acoustically challenged gym, during assemblies you could have a whispered gossip or flirtation with the person next to you or even go to sleep.

One morning the crackly voice of Mr. Srdar, the principal, came over the ancient mesh loudspeakers mounted in every classroom. “Attention students: There will be a special assembly at ten o’clock tomorrow. All students are required to attend.” Rumors flew: was a friendly policeman in uniform coming to talk to us about drugs? Did they finally figure out which teacher was sleeping with his students? The worst scenario was yet another visit from Junior Achievement, touting the virtues of capitalism and on the prowl for future Titans of Industry. If that were the case, at least we could all catch an hour nap.

The next day we trooped into East’s auditorium and reverted to rowdy eight-year-olds; the big room rang with shouts, laughter, and whistles. The principal shushed us down into a quiet roar, and we jostled for seats, seats whose wooden bottoms had been worn so slick and shiny by generations of teenage bottoms that if you slumped or fell asleep you were in danger of sliding to the floor.

Mr. Srdar stood at the podium someone had thoughtfully placed on the left side, where it caught the watery spring light. He introduced the day’s special guest, who would speak to us about the famine in Africa.

This was unexpected and shut us up. We looked from side to side, acknowledging that every single one of us, even kids who couldn’t find the world’s second largest continent on a globe, had been implored to “Think of the starving children in Africa” when staring down a plate of grey meatloaf, calf’s’ liver, or boiled-to-death broccoli, which was supposed to make the disgusting mess more appetizing.

An earnest young man in khakis stepped up to the podium, introduced himself, and spoke about the war in Biafra, waving around a copy of National Geographic. He described the starving children he had seen, their stomachs bloated, their eyes dull. He said when the children’s hair turned red it was a sign that they were dying. Their bodies were not taking in enough nutrients to create the dark hair pigment: a little red-haired African child was a walking corpse.

He was good, so good that no one questioned why he had no photos, only a copy of a magazine, or why, if he was just back from Africa, he was as pale as any Minnesotan in March.

When he made a little choking noise in his throat, and dropped his head, girls all around me started to weep, searching in their bags for Kleenex to blot their tears and blow their noses. Even a few of the boys were squirming and blinking. This went on for a while, the young man droning on with his dramatic descriptions of dying kids and keening mothers. I wondered what the hell is going on here?

Then came the pitch. This nice young man was raising money for the starving children of Africa (no, we still couldn’t just send them our spinach and fish sticks) through a brand new kind of fund-raiser: a Walk-A-Thon, a 20-mile trek through Duluth. To participate, we had to ask our parents, parents’ friends, aunts, uncles, grandparents, any available adult with money in pocket, to sponsor us at so much a mile — preferably a dollar.

He said, “Imagine you’re holding a little African in your arms. Imagine that baby’s scrawny limbs, the distended belly barely covered in rags, the head that seems too large topped with a scruff of tightly curled, rust-colored hair. That baby is looking at you with big brown eyes, pleading for help. If you do not participate in the Save Africa Walk-a-Thon, you are dumping this poor dying baby out of your lap and letting that baby die.“

Even the football players were sniffing now, and some girls were red-faced from bawling. Mr. Srdar dabbed his own wet eyes with a big white hankie, congratulated the young man on the noble work he was doing, and assured him that he could count on East High students.

The Walk-A-Thon was scheduled for that Saturday. We were told the meeting place and instructed to bring our sponsors’ money with us. We were not given sign-up sheets, collection envelopes, buttons, pamphlets, or t-shirts. None of us thought this was odd as we went about pestering parents, family friends, and relatives for money.

I knew better than to ask my own mom, certain what her response would be to giving away money to perfect strangers. My dad and one set of grandparents were Missing In Action, the other grandparents hundreds of miles away. I walked over to Lakeview Avenue, my old block, and knocked on the McCauleys’ door; they were an older couple who were always good for a couple of boxes of Thin Mints or Samoa Girl Scout cookies. I was not nearly as eloquent as the young man and had a hard time explaining why Mrs. McCauley should give me the immense sum of twenty dollars so I could go on a walk. She pulled a crumpled one from a change purse, I took it, thanked her, and headed over to Michael Vlasdic’s house.

Michael was not walking. He had no interest in any extracurricular activities besides listening to records, taking drugs, and screwing me. Always a good sport, Mrs. Vlasdic gave me a twenty and told me I was a gutes Maedchen.

On a bright spring morning, a sympathetic mother delivered me and a passel of my friends to the Walk-a-Thon starting point, where the young man stood with a clipboard, writing down kids’ names, taking their money, handing out blurry mimeographed maps, and thanking us for saving all those babies’ lives.

We were somewhere in West Duluth, a neighborhood I hadn’t been in for years, and then only to visit the small and smelly Duluth Zoo, where an irate, aggressive and way too close squirrel monkey had once tried to snatch my mom’s beehive hairdo off her head. As I squinted at the blurry map, trying to make sense out of all the random rights and lefts, the young man blew a whistle and we headed off en masse.

The first five miles weren’t so bad, we were with our friends, we were outside in the fresh sun of spring, joking and laughing, and extremely proud of ourselves. We were the better angels, the generation that was going to save the world. The next month, on April 22, a bunch of us do-gooders would be down on Park Point beach, celebrating the first Earth Day, saving the planet by creating rickety sculptures of driftwood while tripping on LSD.

By mile 10, there was no more laughter, only silent plodding. We wore flimsy sneakers and carried nothing; running shoes, bottled water, and energy bars had yet to be invented. I don’t know if anyone made it past the fifteen-mile mark. At that point I hobbled home, fell on the couch, and gingerly took off my Keds and ankle socks to reveal swollen, throbbing, blister-covered feet, while my mom yelled at me for being gone all day without calling.

What hurt even worse was finding out that our nice young man was not saving babies, but lining his own pockets. Too late Mr. Srdar got a phone call from a high school in St. Cloud, telling him to be on the lookout for a traveling flimflam man, who like Professor Harold Hill in The Music Man, went from one innocent small town to the next, selling us nothing, not even big trombones or ratatat drums.

Even though I had watched Michael Vlasdic tear up during that hornswoggle of a speech, now he was miffed that I had given away his mom’s twenty dollars, which would have bought four hits of acid.

Since my father had left, my own cash flow had trickled down to nothing. My mom did not have a bank account in her name. It took several phone calls and several weeks before my dad would reluctantly show up to place some actual cash in my mom’s hand. She would then, almost as reluctantly, peel off a few bills for me. From that pittance I had to pay for my share of gas and booze on Friday nights with my pals, and for the drugs Michael and I took on Saturday.

But suddenly it was summer, school was out, and I was sixteen, old enough to find a job. The Flamette, a diner that was swarmed with tourists in the summer, hired high school girls. My friends Nancy, Betsy, and Debbie waitressed there, I looked on, jaw agape, as they competitively counted up their tips after work. I filled out a Flamette application, leaving the “Experience” section blank, and was shown the door.

I next applied to be an A&W carhop; the manager took one look at my scrawny arms and knew that I would immediately dump a tray laden with those heavy glass mugs of root beer and ice cream over myself or a customer.

I lowered my sights to restaurant kitchen work. When we were still a family, my father had spent enough money at the Bellows Steak House that the manager recognized me as I sat in the waiting area on a June afternoon, clutching my application form. He hired me as a salad girl. I would work four nights a week and make $1.90 an hour.

My work night started at four o’clock. My primary duty was preparing the mix for the big salad that came with every dinner and that was ninety percent iceberg lettuce. In the basement prep kitchen I’d give each head of lettuce a good thunk on the bottom and twist out the core as instructed by the scary chef. He had also shown me how to operate the electric lettuce shredder without losing a finger, but I was too terrified of that whirling, deadly contraption to put a hand anywhere near it. Instead I stood across the room and tossed heads of lettuce towards the blades, again and again, gathering the bits that went all over the floor and adding them to the giant plastic salad bin.

I assembled salad after salad so that they could be delivered, cold and crisp, to diners who would smother them with French, Thousand Island, or Roquefort. It was my job to keep the tripart salad dressing servers filled; I never washed those servers, just gave them a quick wipe with a kitchen rag to clean off the crust along the sides of the silvery cups and the top of the ladles.

My other task was making shrimp cocktails, and boy, Duluthians loved their shrimp cocktails. After the eight hundred salads were made and chilling, I pulled a huge bag of shrimp out of the freezer and dunked it in a sink filled with lukewarm water. I spent the next hour peeling and deveining shrimp, stopping to pull out salads for early bird diners and hoping that they wouldn’t order the shrimp cocktail as basically they would get shrimp-flavored ice cubes.

The nadir of my night was when some brave or deluded soul ordered a platter of oysters or clams on the half shell. While unordered shrimp ended up in the next night’s scampi, the restaurant had no use for leftover bivalves, so I could not defrost them in advance. I had to struggle with each frozen shell, holding it under running water, attacking it with an oyster knife, and cutting my own hands to pieces. Then I had to slice a lemon.

Finally, towards the end of the night, with a few hateful customers lingering in the dining room trying to decide if they should have one more Grasshopper or Golden Cadillac or Brandy Alexander, the kitchen would quiet and slow. The cooks scraped black squares of pumice up and down the grill while the waitresses snuck back to my little area to grab a forbidden smoke. I was in awe of these creatures, with their elaborate updos, kabuki eyebrows and eyeliner, and pockets bursting with ones. They paid me no attention at all, I was a mere salad girl, covered in shreds of lettuce and smelling of shrimp.

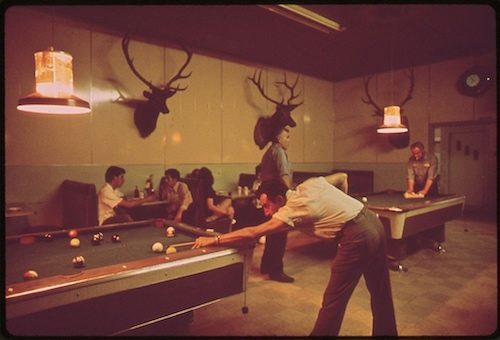

Every week I cashed my paycheck at the Bellow’s and immediately set out to buy drugs, a task that pathologically shy Michael Vlasdic had relegated to me. Even with my onerous work schedule, the freedom of summer meant that Michael and I could trip several times a week. There were kids from East High who could be counted on to have acid, my old admirer Stan now one of them. I could call John Bean; although I was always afraid that he would bring along Doug Figge, he never did. If no one I knew had LSD, I took the bus downtown to the scary, sinister pool hall, where the greasers from Central and Denfeld High hung out, a place that was so forbidden to a nice East High girl that it went unmentioned.

Fortunately, I never had to actually go into that dimly lit den of perdition. I’d poke my head in the doorway, and some long-haired guy in a white tee would nod, follow me out, and lead me to the back alley.

I hated buying drugs at the pool hall, convinced that I was going to be raped, robbed, and murdered by one of the dodgy seventeen-or eighteen-year-old dealers. I pleaded with Michael, “I’ll give you the money, but please, can you go make the buy?” Michael blanched at the idea of talking to a stranger, even one who sold drugs; but I was tired of risking my life. He reluctantly took my money and I felt like the worst girlfriend in the world.

That evening I let myself into the Vlasdic’s house. Michael was lying on the living room floor, staring at the ceiling. I shook him, “Michael. You bought acid right?” He nodded. “Ah, can I have mine?” He shook his head, pointed at his open mouth, and closed his eyes. I disgustedly left him there to trip on his own, went back home straight as a stone, and kept control of the money and the drugs from then on.