“The Thread of Truth, Part IV” by Erle Stanley Gardner

When he died, in 1970, Erle Stanley Gardner was the best-selling American fiction author of the century. His detective stories sold all over the globe, especially those with his most famous defense attorney protagonist, Perry Mason. His no-nonsense prose and neat, satisfying endings delighted detective fans for decades. Gardner wrote several stories that were serialized in the Post. In Country Gentleman, his 1936 serial “The Thread of Truth” follows a fresh D.A. in a clergyman murder case that comes on his first day on the job.

Published on December 1, 1936

The shabby little man, registered as The Reverend Charles Brower, died in Room 321 of the Madison Hotel, murdered by a deadly sleeping tablet. District Attorney Douglas Selby of Madison City, elected on a reform ticket, must find the guilty person, for he knew that the Blade, newspaper of the ousted gang, awaited the chance for a vicious attack.

But Mrs. Brower, come from Nevada to the California town near Hollywood, declared the slain man was not her husband. Yet the few effects in Room 321 were all identified with Brower, all save an expensive camera, a movie scenario, newspaper clippings of the screen favorite, Shirley Arden, and more clippings relating to litigation over the local Perry estate.

Working desperately, Selby learned that Shirley Arden had been a guest of the Madison Hotel the night of the murder, that a man had called upon her, and that a perfumed envelope containing five $1,000 bills had been left in the hotel safe in Brower’s name.

The Blade screamed for action on the case. Selby questioned Shirley Arden, discovered that her distinctive perfume did not tally with that of the envelope, and that she could not remember clearly the name of the man who had called for her aid in selling his scenario. She convinced Selby of her innocence; she even won his reluctant admiration and his promise of protection against the harm that connection with a murder case would do her career.

Then the first break. Spectacles found in Room 321 belonged to a Reverend Larrabie of Riverbend, upstate California town. It was the name Shirley Arden had been trying to recall! Selby and his staunch ally, Sylvia Martin, girl reporter on the friendly Clarion, hastened to Riverbend to return with Mrs. Larrabie. The slain man was her husband, but his murderer was yet to be found.

Then Brower appeared at the hotel to demand the $5,000 envelope, but refused to talk when taken into custody. Next Selby discovered that young Herbert Perry, one of the Perry estate litigants, had knocked on the door of the minister’s room the night of the murder. And then, to Selby’s dismay, Sylvia Martin pointed out that Shirley Arden had suddenly changed the brand of perfume she used — and the change coincided with the time of the minister’s death.

XIII

Events during the next few minutes moved in a swift, kaleidoscopic fashion.

Frank Gordon entered the office very much excited. There had been a shooting scrape down on Washington Avenue. A divorced husband had vowed no one else should have his wife and had sought to make good his boast with five shots from a six-shooter, saving the sixth for himself. Four of the shots had gone wild. The woman had been wounded with the fifth. The man’s nerve had failed when it came to using the sixth. He’d turned to run and had been picked up by one of the officers.

Held in jail, he was filled with lachrymose repentance and was in the proper mood to make a complete confession. Later on he probably would repudiate the confession, claim the police had beaten him in order to obtain it, that he had shot in self-defense and was insane anyway. Therefore, the police were anxious to have the district attorney present to see that a confession was taken down properly.

“You’ll have to go, Gordon,” Selby said. “This will be a good chance for you to break in. Remember not to make him any promises. Don’t even go so far as to tell him it would be better for him to tell the truth. Take a shorthand reporter with you and take down everything that’s said; ask the man if he wants a lawyer.”

“Should I do that?”

“Sure. He won’t want a lawyer — not now, when he wants to confess. Later on he’ll want a lawyer, or perhaps some lawyer will want him in order to get the advertising. How bad is the woman wounded?”

“Not bad; a shot through the shoulder. It missed the lung, I understand.”

“If it isn’t fatal he’ll plead guilty,” Selby said. “If it kills her, he’ll fight to beat the noose. Get him tied up while he’s in the mood.”

Gordon went out, and Sylvia smiled across at Selby.

“If cases would only come singly,” she said, “but they don’t.”

“No,” he told her, “they don’t, and this Larrabie case is a humdinger.”

The telephone rang.

“That,” Selby said, squaring his jaw, “will be Ben Trask.”

But it wasn’t Ben Trask; it was Harry Perkins, the coroner, and for once his slow, drawling speech was keyed up to an almost hysterical pitch.

“I want you to come down here right away, Selby,” he said, “there’s hell to pay.”

Selby stiffened in his chair.

“What’s the matter?” he asked. “A murder?”

“Murder nothing. It’s ten times worse than a murder,” he said, “it’s a dirty damn dog poisoner.”

For the moment Selby couldn’t believe his ears.

“Come on down to earth,” he said, “and tell me the facts.”

“My police dog, Rogue,” the coroner said; “somebody got him, with poison. He’s at the vet’s now. Doc’s working on him. It’ll be touch and go, with one chance in ten for the dog.”

He broke off with something which sounded very much as though he had choked back a sob.

“Any clues?” Selby asked.

“I don’t know. I haven’t had time to look. I just found him and rushed him down to the veterinary’s. I’m down at Doctor Perry’s hospital now.”

“I’ll come down and see what can be done,” Selby said.

He hung up the telephone and turned to Sylvia Martin.

“That,” he said, “shows how callous we get about things which don’t concern us, and how worked up we get when things get close to home. That’s Harry Perkins, the coroner. He’s been out on murder cases, suicides, automobile accidents and all forms of violent death. He’s picked up people in all stages of dilapidation, and to him it’s been just one more corpse. Tears, entreaties and hysterics mean nothing to him. He’s grown accustomed to them. But somebody poisoned his dog, and damned if he isn’t crying.”

“And you’re going down to see about a poisoned dog?” Sylvia Martin asked.

“Yes.”

“Good Lord, why?”

“In the first place, he feels so cut up about it and, in a way, he’s one of the official family. In the second place, he’s down at Doctor Perry’s Dog and Cat Hospital — you know, Dr. H. Franklin Perry, the brother who stands to inherit the money in the Perry Estate if young Herbert Perry loses out.”

“Well?” she asked.

“I’ve never talked with Doctor Perry,” Selby said. “The sheriff’s office found he didn’t know anything about the man who was killed, and let it go at that, but somehow I want to take a look at him.”

“Anything except a hunch?” she asked.

“It isn’t even that,” he said; “but if that morphine was deliberately mixed in with the sleeping tablets, it must have been done by someone who had access to morphine, and who could have fixed up a tablet. Doctor Perry runs a veterinary hospital and … ”

“Forget it,” she told him. “That whole thing was a plant, along with the letter. Larrabie never took that sleeping medicine. Not voluntarily, anyway. His wife said he never had any trouble sleeping. Don’t you remember?”

Selby nodded moodily.

“Moreover,” she pointed out, “when it comes to suspicions, you can find lots of people to suspect.”

“Meaning?” he asked.

“Meaning,” she said, “that I’ve never been satisfied with this man Cushing’s explanations.

“In the first place, the way he shields Shirley Arden means that in some way she’s more than just a transient customer who occasionally comes up from Los Angeles. In the second place, he didn’t disclose anything about that five thousand dollars in the safe until pretty late. In the third place, he was so blamed anxious to have it appear the death was accidental.

“Now, whoever wrote that letter and addressed the envelope was someone who didn’t know the man’s real identity. The only thing he knew was what he’d picked up from the hotel register.”

“Therefore, the murderer must have been someone who had access to the information on the hotel register. And, aside from what he could learn from that register, he didn’t know a thing about the man he killed. Therefore, he acted on the assumption that his victim was Charles Brower.

“He wanted to make the murder appear like suicide, so he wrote that letter and left it in the typewriter. If the man had really been Charles Brower, nothing would ever have been thought of it. The post-mortem wouldn’t have been continued to the extent of testing the vital organs for morphine. And, even if they had found some morphine, they’d have blamed it on the sleep medicine.

“Now, the person who would have been most apt to be misled by the registration would have been the manager of the hotel.”

“But what possible motive could Cushing have had for committing the murder?”

“You can’t tell until you find out what the bond is between Cushing and Shirley Arden. I can’t puzzle it all out, I’m just giving you a thought.”

His eyes were moody as he said slowly, “That’s the worst of messing around with one of these simple-appearing murder cases. If someone sneaked into the room and stabbed him, or had shot him, or something like that, it wouldn’t have been so bad, but … Oh, hang it, this case had to come along right at the start of my term of office.”

“Another thing,” she said, “to remember is that the person who wrote the letter, and probably the person who committed the murder, got in there from 319. Now, there wasn’t anyone registered in 319. That means the person must have had a passkey.”

“I’ve thought of all that,” Selby said. “The murderer could hardly have come in through the transom, couldn’t have come in through the door of 321, and he couldn’t have come in through the door of 323 — that is, what I really mean is, he couldn’t have gone out that way. He could have gotten in the room by a dozen different methods. He could have been hiding in the room, he could have walked in through the door of 321, he could have gone in through 323. After all, you know, we don’t know that the door wasn’t barricaded after the man had died. From what Herbert Perry says, someone must have been in the room some two or three hours after death took place.

“But when that man went out he had only one way to go, and that was through the door of 319. If he’d gone out through 323, he couldn’t have bolted the door from the inside. If he’d gone out through the door of 321, he couldn’t have barricaded the door with a chair. There was no chance he could have gone out through the window. Therefore, 319 represents the only way he could have gone out.”

“And he couldn’t have gone out that way,” she said, “unless he’d known the room was vacant, and had a passkey, and had previously left the communicating door unlocked.”

“That’s probably right.”

“Well,” she said, “it’s up to you, but personally I’d be inclined to look for an inside job around the hotel somewhere, and I think Cushing is tied up too deeply with this motion-picture actress to be above suspicion. It’s a cinch she was the one who furnished the five thousand dollars.”

“You might,” Selby told her, “do a little work along that line, Sylvia. I wouldn’t want to get hard-boiled with Cushing unless I had something to work on, because, after all, we haven’t the faintest semblance of a motive. We … ”

“How about robbery?”

“No, I’ve considered that. If it had been robbery, it would have been an easy matter for Cushing to have taken the envelope with the five thousand dollars out of the safe and substituted another one. He could have made a passable forgery of the signature. Since it wasn’t Brower’s signature in any event, there wouldn’t have been much opportunity to detect the forgery.”

She started for the door, turned to grin at him and said, “On my way. I’ll let you know if anything turns up.”

“The devil of it is,” he told her, “this isn’t like one of those detective stories, which you can solve by merely pointing the finger of suspicion at the guilty person. This is a real life, flesh-and-blood murder case, where we’ve got to produce actual evidence which can stand up in a court of justice. I’ve got to find that murderer and then prove he’s guilty beyond all reasonable doubt.”

“And if you don’t do it?” she asked.

“Wait until you see The Blade tonight,” he said gloomily. “I have an idea Sam Roper is going to make a statement.”

She laughed and said, “Afraid you can’t take it, Doug?”

“No,” he told her. “That’s not what’s worrying me. I know damn well I can take it. What’s worrying me is whether I can dish it out.”

She grinned, said “Go to it, big boy,” and closed the door behind her as she left his private office.

Ten seconds later the telephone rang.

To Selby’s surprise, it was Shirley Arden, herself, at the other end of the wire.

“I think,” he told her, “there are some things we need to have cleared up.”

She hesitated a moment, then said, “I’d be only too glad to talk with you. It’s going to be very difficult for me to come up to Madison City, and you know the position I’m in after the nasty insinuations the newspapers have made. If I showed up there now, they’d have me virtually accused of murder. Couldn’t you come down here?”

“When?”

“Tonight.”

“Where?”

“You know where my house is in Beverly Hills?”

“Yes,” he told her, his voice still savagely official. “I once went on a rubberneck tour. Had an old-maid aunt out from the East. She wanted to see where all of the stars lived. Yours is the place that sits up on a hill, with the fountain in the front yard and the stone lions in front of the porch, isn’t it?”

“That’s the one. Could you be there tonight at eight?”

“Yes.”

“We can have a quiet little dinner — just we two. Don’t say anything about it. In other words, don’t let anyone know you’re coming to see me.”

“Do you know what I want to see you about?” he asked.

“Haven’t the least idea,” she told him cheerfully, “but I’ll be glad to see you under more favorable circumstances than the last visit.”

“The circumstances,” he announced, “won’t be more favorable.”

Her laugh was a throaty ripple as she said, “My, you’re so grim you frighten me. Tonight, then, at eight. Good-by.” She put the receiver on the hook.

Selby grabbed for his hat and started for Doctor Perry’s Dog and Cat Hospital.

…

Doctor Perry looked up as Selby came in. He was in his fifties, a man whose manner radiated quiet determination. A police dog was held in a canvas sling in a long bathtub. His head had drooped forward. His tongue lolled from his mouth. His eyes were dazed.

Doctor Perry’s sleeves were rolled up, his smock was stained and splashed. In his right hand he held a long, flexible rubber tube connected with a glass tank. He slightly compressed the end of the tube and washed out the sides of the bathtub.

“That’s all that can be done,” he said. “I’ve got him thoroughly cleaned out and given him a heart stimulant. Now we’ll just have to keep him quiet and see what happens.”

He lifted the big dog as tenderly as though it had been a child, carried it to a warm, dry kennel on which a thick paper mattress had been spread.

Harry Perkins blew his nose explosively. “Think he’ll live?” he asked.

“I can tell you more in a couple of hours. He had an awful shock. You should have got him here sooner.”

“I got him here just as quickly as I could. Do you know what kind of poison it was?”

“No, it was plenty powerful, whatever it was. It doesn’t act like anything I’ve encountered before.”

“This is the district attorney,” Perkins said.

Doctor Perry nodded to Selby and said, “Glad to meet you.”

Perkins said, “Doug, I don’t care how much it costs, I want this thing run to the ground. I want to find the man who poisoned that dog. Rogue has the nicest disposition of any dog in the world. He’s friendly with everyone. Of course, he’s a good watchdog. That’s to be expected. If anyone tries to get in my place and touch anything, Rogue would tear him to pieces. He’s particularly friendly to children. There isn’t a kid in the block but what knows him and loves him.”

The veterinarian fitted the hose over one of the faucets in the bathtub, cleaned out the bathtub, washed off his hands and arms, took off the stained smock and said, “Well, let’s go out to your place and take a look around. I want to see whether it’s general poison which has been put around through the vicinity, or something which was tossed into your yard where your dog would get it.”

“But why should anyone toss anything in to Rogue in particular?”

The veterinarian shrugged his shoulders. “Primarily because he’s a big dog,” he said. “That means when he scratches up lawns, he digs deep into the grass. It’s not often people deliberately poison any particular dog unless he’s a big dog, or unless it’s a little dog who’s vicious. Small, friendly dogs are mostly poisoned from a general campaign. Big dogs are almost always the ones who get singled out for special attention.”

“Why do people poison dogs?” Selby asked.

“For the same reason some people rob and murder,” the veterinarian said. “People in the aggregate are all right, but there’s a big minority that have no regard for the rights of others.”

“To think of a man deliberately throwing a dog poisoned food,” Perkins declared, “makes my blood boil. I’d shoot a man who’d do it.”

“Well, let’s take a run over to your place and look around,” Doctor Perry suggested. “You say the dog hasn’t been out of the yard? We may find some of the poison left there and learn something from it.” “How about Rogue? Can we do him any good staying here?”

“Not a bit. To tell you the truth, Harry, I think he’ll pull through. I’m not making any promises, but I hope he’s over the worst of it. What he needs now is rest. My assistant will keep him under close observation. Have you got your car here?”

“Yes.”

“Good. We’ll drive over with you.”

The three of them drove to the place where Perkins had his undertaking establishment, with living quarters over the mortuary. In back of the place was a fenced yard which led to an alley. There was a gate in the alley.

“The dog stayed in here?” Doctor Perry asked.

“Yes. He’s always in the building or here in the yard.”

Doctor Perry walked around the back yard, looking particularly along the line of the fence. Suddenly he stooped and picked up something which appeared to be a ball of earth. He broke it open and disclosed the red of raw meat.

“There you are,” he said; “another little deadly pellet. That’s been mixed by a skillful dog poisoner. He put the poison in raw hamburger, then he rolled the hamburger in the earth so it would be almost impossible to see. A dog’s nose would detect the raw meat through the coating of earth, but your eye would be fooled by the earth which had been placed around it. Let’s look around and see if we can find some more.”

A survey of the yard disclosed two more of the little rolls of poisoned meat.

“Notice the way these were placed along the sides of the fence,” Selby said to the coroner. “They weren’t just tossed over the fence, but were deliberately placed there. That means that someone must have walked through the gate and into the back yard.”

“By George, that’s so!” Perkins exclaimed.

“That’s undoubtedly true,” Doctor Perry agreed. “Now, then, if the dog were here in the yard, why didn’t he bark? Moreover, why didn’t the poisoner stand in the alley and just toss the rolls of meat in to the dog?”

Perkins turned to the district attorney and asked, “What can you do to a dog poisoner, Selby?”

“Not a great deal,” Selby admitted. “It’s hard to convict them, if they stand trial. And when they are convicted a judge usually gives them probation.”

“To my mind,” Perry said, “they should be hung. It’s a worse crime than murder.”

“That’s exactly the way I feel about it,” Perkins agreed emphatically.

They walked back through the yard into the back room of the mortuary.

“We’d better take a look around here, too,” Perry suggested. “This commences to look like an inside job to me. It looks as though someone you’d been talking to had casually strolled around here and planted this stuff. Can you remember having had anyone roaming around the place, Harry? It must have been someone who planted the poison right while you were talking with him.”

“Why, yes,” Perkins said, “there were several people in here. I had a coroner’s jury sitting on the inquest on the man who was murdered in the hotel.”

He turned to Selby and said, “That was yesterday, while you were gone. They returned a verdict of murder by person or persons unknown. I presume you knew that.”

“I gathered they would,” Selby remarked. “It seems the only possible verdict which could have been returned.”

He turned to Perry and said, “I’m wondering if you knew the dead man, Doctor.”

“No, I’d never seen him in my life — not that I know of.”

Selby took a photograph from his inside coat pocket, showed it to Doctor Perry.

“I wish you’d take a good look at that,” he said, “and see if it looks at all familiar.”

Doctor Perry studied it from several angles and slowly shook his head. “No,” he said. “The sheriff asked me about him, and showed me the same picture. I told the sheriff I’d never seen him, but now, looking at this photograph, I somehow get the impression I’ve seen him somewhere. You know, the face has a vaguely familiar look. Perhaps it’s just a type. I can’t place him, but there’s something about him that reminds me of someone.”

Selby was excited. “I wish you’d think carefully,” he said. “You know the man had some clippings in his briefcase about the litigation you’re interested in.”

“Yes, the sheriff told me that he did,” Perry said, “but lots of people are interested in that case. I’ve had lots of letters about it. You see, quite a few people got interlocutory decrees and then went into another state to get married. They’re worried about where they’d stand on inheritances and such. That’s probably why this man was interested … But he reminds me of someone; perhaps it’s a family resemblance. Let me see what clippings he cut out, and I may be able to tell you more about him. I must have had a hundred letters from people who sent clippings and asked for details.”

“Ever answer the letters?” Selby asked.

“No. I didn’t have time. It keeps me busy running my own business. Paying off the mortgage on this new hospital keeps my nose to the grindstone. I wish that lawsuit would get finished; but my lawyer says it’s about over now. I couldn’t pay him a regular fee, so he took it on a contingency. He’ll make almost as much out of it as I will.”

“Hope he does,” the coroner said. “He owes me a nice little sum on a note that’s overdue.”

The coroner took out the briefcase, suitcase and portable typewriter. “By the way,” he asked, “is it all right to deliver these to the widow? She was in to get them a while ago.”

“I think so,” Selby said, “but you’d better ask the sheriff and get his okay.”

“I did that already. He says it’s okay by him, if it is by you.”

“Go ahead and give them to her then. But be sure the inventory checks.”

The coroner opened the suitcase, also the briefcase.

“Well,” Selby said, “I’m going to be getting on back to the office. Perhaps Doctor Perry can tell us something after his examination of those poisoned scraps.”

“Wait a minute,” the veterinarian said, laying down the newspaper clippings the coroner had handed him. “What’s that over there in the corner?”

Perkins stared, then said, “Good Lord, it’s another one of the same things.”

They walked over and picked it up. Perry examined it, then dropped it into his pocket.

“That settles it,” he announced. “It was aimed directly at your dog and it’s an inside job, someone who’s been in here today. Can you remember who was in here?”

“The last man in here today,” Perkins said, “was George Cushing, manager of the Madison Hotel. It’s a cinch he wouldn’t have done anything like that.”

“No,” Selby said, “we’d hardly put Cushing in the category of a dog poisoner.”

“Who else?” the veterinarian asked.

“Mrs. Larrabie was in here, the dead man’s widow. She looked over the things in the suitcase and in the briefcase. And Fred Latteur, your lawyer. He came in to tell me he’d pay off my note when he had your case settled. He wouldn’t have any reason to poison the dog.”

“Let’s take a look around and see if we can find some more,” Doctor Perry said. “Each one of us take a room. Make a thorough search.”

They looked through the rooms and Selby found another of the peculiarly distinctive bits of poisoned meat.

“Anyone else been in here today?” Selby demanded. “Think carefully, Perkins. It’s important. There’s more to this than appears on the surface.”

“No … Wait a minute, Mrs. Brower was in. She’s on the warpath,” the coroner said. “She thought I had five thousand dollars that had been taken from the hotel. She insists that it’s her husband’s money.”

“Did she say where he got it?”

“She said Larrabie had Brower’s wallet, and that the five thousand-dollar bills had been in Brower’s wallet. Therefore, Brower was entitled to them.”

“What did she want you to do?”

“She wanted me to give her the money. When I told her I didn’t have it, she wanted to take a look at the wallet. She said she could tell whether it was her husband’s.”

“Did you show it to her?”

“The sheriff has it. I sent her up to the sheriff’s office.”

Selby said abruptly, “You can give the rest of the stuff back to Mrs. Larrabie, Harry. I’m going to take that camera. Tell her she can have the Camera in a day or two, but I want to see if there are any exposed films in it. They might furnish a clue. I’ve been too busy to give them any thought, but they may be important.”

“A darned good idea,” the coroner said. “That chap came down here from the northern part of the state. He probably took photographs en route. Those camera fiends are just the kind to put their friends on the front steps of the capitol building at Sacramento and take a bunch of snapshots. You may find something there that’ll be worthwhile.”

Selby nodded and pocketed the camera.

“You let me know about that dog,” Perkins said anxiously to the veterinarian. Then he turned to Selby: “I want something done about this poisoning. At least drag these people who’ve been in here for questioning. And I’d start with Mrs. Brower. She looks mean to me.”

“I’ll give you a ring in an hour or two,” Selby promised. “I’m pretty busy on that murder case, but I have a hunch this poisoning business may be connected somehow with that case. I’ll do everything I can.”

“It’s commencing to look,” Doctor Perry said, “as though this wasn’t any casual poisoning, but something that had been carefully planned to get Rogue out of the way. I’d guard this place day and night for a while, if I were you, Perkins.”

Selby said, “Good idea,” and left Perkins and the veterinarian talking as he started for his office.

XIV

Selby felt absurdly conspicuous as he parked his car in front of the actress’ residence. There was something about the quiet luxury of the place which made the stone Peiping lions on either side of the porch stairway seem as forbidding as vicious watchdogs.

Selby climbed the stairs. The vine-covered porch gave a hint of cool privacy for the hot days of summer.

A military-appearing butler, with broad, straight shoulders, thin waist and narrow hips, opened the door almost as soon as Selby’s finger touched the bell button. Looking past him to the ornate magnificence of the reception hallway and the living room which opened beyond, Selby felt once more that touch of awkward embarrassment, a vague feeling of being out of place.

That feeling was dissipated by the sight of Shirley Arden. She was wearing a cocktail gown, and he noticed with satisfaction that, while there was a touch of formality in her attire, it was only the semi-formality with which one would receive an intimate friend. When she came toward him she neither presumed too much on their previous acquaintance, nor was she distant. She gave him her hand and said, “So glad you could come, Mr. Selby. We’d probably have felt a little more businesslike if we’d dined in one of the cafes; but under the circumstances, it wouldn’t do for us to be seen together.

“The spaciousness of all of this is more or less a setting. I have to do quite a bit of entertaining, you know. Just the two of us will rattle around in here like two dry peas in a paper bag, so I’ve told Jarvis to set a table in the den.”

She slipped her arm through his and said, “Come on and look around. I’m really proud of this architecture.”

She showed him through the house, switching lights on as she walked. Selby had a confused, blurred recollection of spacious rooms, of a patio with a fountain, a private swimming pool with lights embedded in the bottom of the tank so that a tinted glow suffused the water, basement sport rooms with pool, billiard and ping pong tables, a cocktail room with a built-in bar, mirrors and oil paintings which were a burlesque on the barroom paintings of the nineties.

They finished their tour in a comfortable little book-lined den, with huge French doors opening out to a corner of a patio on one side, the other three sides lined with bookcases, the books leather-backed, deluxe editions.

Shirley Arden motioned him to a seat, flung herself into one of the chairs, and raised her feet to an ottoman with a carelessly intimate display of legs.

She stretched out her arms and said wearily, “Lord, but it was a trying day at the studio. How’s the district-attorney business going?”

“Not so good,” he told her, his voice uncompromisingly determined.

The butler brought them cocktails and a tray of appetizers, which he set on the coffee table between them. As they clicked the rims of their glasses, Selby noticed the butler placing the huge silver cocktail shaker, beaded with frosty moisture, upon the table.

“I don’t go in for much of this, you know. And, after all, this visit is official,” Selby said.

“Neither do I,” she told him, laughing, “but don’t get frightened at the size of the container. That’s just Hollywood hospitality. Don’t drink any more than you want. There’s an inner container in that cocktail shaker, so the drink will keep cold as ice without being diluted by melting ice. You can have just as much or as little as you want.

“You know, we who are actively working in pictures don’t dare to do much drinking. It’s the people who are slipping on the downward path toward oblivion who hit it heavy. And there are always a lot of hangers-on who can punish the liquor. Try some of those anchovy tarts with the cream cheese around them. It sounds like an awful combination, but I can assure you they’re really fine. Jarvis invented them, and there are a dozen hostesses in town who would scratch my eyes out to get the recipe for that cream cheese sauce.”

Selby began to feel more at home. The cocktail warmed him, and there was a delightful informality about Shirley Arden which made the spacious luxury of the house seem something which was reserved for mere formal occasions, while the warm intimacy of this little den gave the impression of having been created entirely for Selby’s visit. He found it impossible to believe her capable of deceit.

She put down her empty cocktail glass, smiled, and said unexpectedly, with the swift directness of a meteor shooting across a night sky, “So you wanted to see me about the perfume?”

“How did you know?” he asked.

“I knew perfume entered into the case somewhere,” she said, “because of the very apparent interest you took in the perfume I used.

“As a matter of fact, I changed my perfume either one or two days before, I’ve forgotten which, on the advice of an astrologer. You don’t believe in astrology, do you?”

He didn’t answer her question directly, but asked, “Why did you change your perfume? “

“Because I was informed that the stars threatened disaster, if I didn’t … Oh, I know it sounds so absolutely weird and uncanny when one says it that way, but there are lots of things which seem perfectly logical in the privacy of your own mind which look like the devil when you bring them out into public conversation. Don’t you think so?”

“Go on,” he told her. “I’m listening.”

She laughed and flexed her muscles as some cat might twist and stretch in warm sunlight; not the stretch of weariness, but that sinuous, twisting stretch of excess animal vitality seeking outlet through muscular activity.

“Do you know,” she said, “we are hopelessly ignorant about the most simple things of life. Take scent, for instance. A flower gives forth a scent. A man gives forth a scent. Every living thing has some odor associated with it. I can walk down this path” — and she made a sweeping, graceful gesture toward the patio beyond the French windows — “with my feet incased in leather. Each foot rests on the ground for only a fifth of a second, if I’m walking rapidly. Yet my life force throws off vibrations. The very ground I have walked on starts vibrating in harmony with the rhythm of my own vibrations. We can prove that by having a bloodhound start on my trail. His nose is attuned to the vibrations which we call odor, or scent. He can detect unerringly every place where I have put my foot.

“Women use scent to enhance their charm. It emphasizes, in some way, the vibration they are casting forth, vibrations which are emanating all the time. One scent will go fine with one personality, yet clash with another. Do you see what I mean?”

“I’m still listening,” Selby told her. “And the anchovy tarts are delicious.”

She laughed, glanced swiftly at him. There was almost a trace of fear in her eyes and more than a trace of nervousness in her laugh.

“There’s something about you,” she said, “which frightens me. You’re so … persistently direct.”

“Rude?” he asked.

“No,” she said, “it’s not rudeness. It’s a positive, vital something. You’re boring directly toward some definite objective in everything you do.”

“We were talking,” he told her, “about the reason you changed your perfume.”

“For some time,” she said, “I’ve known that I was — well, let us say, out of step with myself. Things haven’t been going just right. There were numerous little irritations which ordinarily I’d have paid no attention to. But recently they began to pile up. I began to lose that inner harmony, that sense of being in tune with the rhythm of existence — if you know what I mean?”

“I think I understand, yes.”

“I went to an astrologer. She told me that my personality was undergoing a change, and I can realize she’s correct. Now that I look back on it, I think every successful picture actress goes through at least two distinct phases of development. Very few of us are born to the purple. We’re usually recruited from all walks of life — stenographers, waitresses, artists’ models. We’re a peculiar lot. We nearly always have a wild streak, which makes us break loose into an unconventional form of life. I don’t mean immorality. I mean lacy of conventional routine.

“Then we get a tryout. We’re given minor parts. We are given a major part. If it’s a poor story with poor direction and poor support, that’s all there is to it. But occasionally it’s a good story with good direction, something outstanding. A new personality is flashed on the screen to the eyes of theatergoers, and the effect is instantaneous. Millions of people all over the world suddenly shower approval upon that new star.

“On the legitimate stage, if an actress is a success, she receives a thunder of applause from the five hundred to fifteen hundred people who compose an audience. The next night she may not be doing so well. The audience may not be quite so responsive. If she does achieve success, it will be through constant repetition before numerous audiences. But, in the picture business, one picture is made, the moods of an actress are captured, imprisoned in a permanent record. That record is flashed simultaneously before hundreds of thousands of audiences, comprising millions of people. That’s why acclaim is so rapid.”

He nodded.

“Let me fill up your cocktail glass.”

“No,” he told her, “one’s plenty.”

“Oh, come on,” she coaxed, “have half a one. I want one more and I don’t want to feel conspicuous.”

“Just half a one, then,” he said.

She didn’t try to take advantage of his acquiescence, but was scrupulously careful to pause when his glass was half full. She filled her own, raised it to her lips and sipped it appreciatively.

“I’m trying to tell you this in detail,” I she said, “because I’m so darned anxious to have you understand me, and to understand my problems.”

“And the reason for changing the perfume,” he reminded her.

“Don’t worry,” she remarked; “I won’t try to dodge the question — not with such a persistent cross-examiner.

“Well, anyway, an actress finds herself catapulted into fame, almost overnight. The public takes a terrific interest in her. If she goes out to a restaurant, she’s pointed out and stared at. On the street, people driving automobiles suddenly recognize her and crane their necks in complete disregard of traffic. The fan magazines have published article after article about the other stars. Now they’re crazy to satisfy reader demand for a new star. They have perfectly fresh material to work with. They want to know every little intimate detail about the past.

“Of course, lots of it’s hooey. Lots of it isn’t. People are interested. I’m not conceited enough to think they’re interested entirely in the star. They’re interested in the spectacle of some fellow mortal being shot up into wealth, fame and success.

“Every girl working as a stenographer, every saleslady standing with aching feet and smiling at cranky customers, every waitress listening to the fresh cracks of the wise-guys in some little jerkwater, greasy-spoon eating joint, realizes that only a few months ago this star who is now the toast of the world was one of them. It’s a story of success which they might duplicate. It’s Cinderella come true.

“No wonder a star’s personality changes. She emerges from complete obscurity, drab background and usually a very meager idea of the formalities, into the white light of publicity. Visiting notables want to lunch with her; money pours in on her; there’s pomp, glitter, the necessity of a complete readjustment. An actress either breaks under that, or she achieves poise. When she achieves poise, she’s become a different personality, in a way.”

“And why did you change your perfume?”

“Because I’ve passed through that stage and didn’t realize it. I’d been using the same perfume for months. And during those months I’ve been undergoing a transition of personality.”

She pressed an electric button. Almost instantly the butler appeared with a steaming tureen of soup.

“Let’s eat,” she said, smiling. “We’re having just a little informal dinner. No elaborate banquet.” He seated her at the table. The butler served the soup. When he had retired, she smiled across at Selby and said, “Now that that’s explained, what else do we talk about?”

Selby said slowly: “We talk about the brand of perfume you used before you made the change, and whether you were still using this same brand of perfume on last Monday, when you stayed at the Madison Hotel. And we once more talk about why you made the change.”

She slowly lowered her spoon to her plate. The elation had vanished from her manner.

“Go ahead and eat,” she said wearily; “we’ll talk it over after dinner — if we must.”

“You should have known,” he told her, “that we must.”

She sighed, picked up her spoon, tried to eat the soup, but her appetite had vanished. She was conscious of her obligations as hostess, but when the butler removed her soup dish it was more than two-thirds filled.

A salad, steak, vegetables and dessert were perfectly cooked and served. Selby was hungry, and ate. Shirley Arden was like some woman about to be led to the executioner and enduring the irony of that barbaric custom which decrees that one about to die shall be given an elaborate repast.

She tried to keep up conversation, but there was no spontaneity to her words.

At length, when the dessert had been finished and the butler served a liqueur, she raised her eyes to Selby and said with lips which seemed to be on the verge of trembling, “Go ahead.”

“What perfume did you use on Monday, the old or the new?”

“The old,” she said.

“Precisely what,” he asked her, shooting one question at her when she expected another, “is your hold on George Cushing?”

She remained smiling, but her nostrils slightly dilated. She was breathing heavily. “I didn’t know that I had any hold on him,” she said.

“Yes, you did,” Selby told her. “You have a hold on him and you use it. You go to Madison City and he protects your incognito.”

“Wouldn’t any wise hotel manager do that same thing?”

“I know Cushing,” Selby said. “I know there’s some reason for what he does.”

“All right,” she said wearily, “I have a hold on him. And the perfume which you smelled on the five thousand dollars was the perfume which I used. And Cushing telephoned to me in Los Angeles to warn me that you were suspicious; that you’d found out I’d been at the hotel; that you thought the five thousand-dollar bills had been given to Larrabie by me. So what?”

For a moment Selby thought she was going to faint. She swayed in her chair. Her head drooped forward.

“Shirley!” he exclaimed, unconscious that he was using her first name.

His hand had just touched her shoulder, when a pane of glass in the French window shattered. A voice called, “Selby! Look here!”

He looked up to see a vague, shadowy figure standing outside the door. He caught a glimpse of something which glittered, and then a blinding flash dazzled his eyes. Involuntarily he blinked and, when he opened his eyes, it seemed that the illumination in the room was merely a half darkness.

He closed his eyes, rubbed them. Gradually the details of the room swam back into his field of vision. He saw Shirley Arden, her arms on the table, her head drooped forward on her arm. He saw the shattered glass of the windowpane, the dark outline of the French doors.

Selby ran to the French door, jerked it open. His eyes, rapidly regaining their ability to see, strained themselves into the half-darkness.

He saw the outlines of the huge house, stretching in the form of an open U around the patio, the swimming pool with its colored lights, the fountain which splashed water down into a basin filled with water lilies, porch swings, tables shaded by umbrellas, reclining chairs — but he saw no sign of motion.

From the street, Selby heard the quick rasp of a starting motor, the roar of an automobile engine, and then the snarling sound of tires as the car shot away into the night.

Selby turned back toward the room. Shirley Arden was as he had left her. He went toward her, placed a hand on her shoulder. Her flesh quivered beneath his hand.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “it’s just one of those things. But you’ll have to go through with it now.”

He heard the pound of heavy, masculine steps, heard the excited voice of the butler, then the door of the den burst open and Ben Trask, his face twisting with emotion, stood glaring on the threshold.

“You cheap shyster!” he said. “You damned publicity-courting, doublecrossing … ”

Selby straightened, came toward him. “Who the devil are you talking to?” he asked.

“You!”

Shirley Arden was on her feet with a quick, panther-like motion. She dashed between the two men, pushed against Trask’s chest with her hands. “No, no, Ben!” she exclaimed. “Stop it! You don’t understand. Can’t you see … ”

“The devil I don’t understand,” he said. “I understand everything.”

“I told him,” she said. “I had to tell him.”

‘Told him what?”

“Told him about Cushing, about . . .”

“Shut up, you little fool.”

Selby, stepping ominously forward, said, “Just a minute, Trask. While you may not realize it, this visit is in my official capacity and … ”

“You and your official capacity both be damned!” Trask told him. “You deliberately engineered a cheap publicity stunt. You wanted to drag Shirley Arden into that hick-town murder inquiry of yours so you’d get plenty of publicity. You deliberately imposed on her to set the stage, and then you arrange to have one of your local newshounds come on down to take a flashlight. “Can’t you see it, Shirley?” Trask pleaded. “He’s double-crossed you. He’s … ”

Selby heard his voice saying with a cold fury, “You, Trask, are a damned liar.”

Trask pushed Shirley Arden away from him with no more effort than if she had been some gossamer figure without weight or substance.

He was a big, powerful man, yet he moved with the swiftness of a heavyweight pugilist and, despite his rage, his advance was technically correct — left foot forward, right foot behind, fists doubled, right arm across his stomach, left elbow close to the body.

Something in the very nature of the man’s posture warned Selby of that which he might expect. He was dealing with a trained fighter.

Trask’s fist lashed out in a swift, piston-like blow for Selby’s jaw.

Selby remembered the days when he had won the conference boxing championship for his college. Automatically his rage chilled until it became a cold, deadly, driving purpose. He moved with swift, machinelike efficiency, pivoting his body away from the blow, and, at the same time, pushing out with his left hand just enough to catch Trask’s arm, throw Trask off balance and send the fist sliding over his shoulder.

Trask’s face twisted with surprise. He swung his right up in a vicious uppercut, but Selby, with the added advantage of being perfectly balanced, his weight shifted so that his powerful body muscles could be brought into play, smashed over a terrific right.

His primitive instincts were to slam his fist for Trask’s face, just as a person yielding to a blind rage wants to throw caution to the winds, neglect to guard, concentrate only on battering the face of his opponent. But Selby’s boxing training was controlling his mind. His right shot out straight for Trask’s solar plexus.

He felt his fist strike the soft, yielding torso, saw Trask bend forward and groan.

From the corner of his eye, Selby was conscious of Shirley Arden, her rigid forefinger pressed Against the electric push button which would summon the butler.

Trask staggered to one side, lashed out with a right which grazed the point of Selby’s jaw, throwing him momentarily off balance.

He heard Shirley Arden’s voice screaming, “Stop it, stop it! Both of you! Stop it! Do you hear?”

Selby sidestepped another blow, saw that Trask’s face was gray with pain, saw a rush of motion as the broad-shouldered butler came running into the room, saw Shirley Arden’s outstretched forefinger pointing at Trask. “Take him, Jarvis,” she said.

The big butler hardly changed his stride. He went forward into a football tackle.

Trask, swinging a terrific left, was caught around the waist and went down like a tenpin. A chair crashed into splintered kindling beneath the impact of the two men.

Selby was conscious of Shirley Arden’s blazing eyes.

“Go!” she commanded.

The butler scrambled to his feet. Trask dropped to the floor, his hands pressed against his stomach, his face utterly void of color.

“Just a minute,” Selby said to the actress, conscious that he was breathing heavily. “You have some questions to answer.”

“Never!” she blazed.

Trask’s voice, sounding flat and toneless, said, “Don’t be a damned fool, Shirley. He’s framed it all. Can’t you see?”

The butler turned hopefully toward Selby.

“Don’t try it, my man,” Selby said.

It was Shirley Arden who pushed Jarvis back.

“No,” she said, “there’s no necessity for any more violence. Mr. Selby is going to leave.”

She came toward him, stared up at him.

“To think,” she said scornfully, “that you’d resort to a trick like this. Ben warned me not to trust you. He said you’d deliberately planned to let the news leak out to the papers; that you were trying to put pressure on me until I’d break. I wouldn’t believe him. And now — this — this despicable trick.

“I respected you. Yes, if you want to know it, I admired you. Admired you so much I couldn’t be normal when I was with you. Ben told me I was losing my head like a little schoolgirl.

“You were so poised, so certain of yourself, so absolutely straightforward and wholeheartedly sincere that you seemed like pure gold against the fourteen-carat brass I’d been associating with in Hollywood. And now you turn out to be just as rotten and just as lousy as the rest of them. Get out!”

“Now, listen,” Selby said; “I’m … ”

The butler stepped forward. “You heard what she told you,” he said ominously. “Get out!”

Shirley Arden turned on her heel.

“He’ll get out, Jarvis,” she said wearily. “You won’t have to put him out — but see that he leaves.”

“Miss Arden, please,” Selby said, stepping forward, “you can’t … ”

The big butler tensed his muscles. “Going someplace,” he said ominously, “besides out?”

Shirley Arden, without once looking back over her shoulder, left the room. Ben Trask scrambled to his feet.

“Watch him, Jarvis,” Trask warned; “he’s dynamite. What the hell did you tackle me for?”

“She said to,” the butler remarked coolly, never taking his eyes off Selby.

“She’s gone nuts over him,” Trask said.

“Get out,” the butler remarked to Selby.

Selby knew when he was faced with hopeless odds.

“Miss Arden,” he said, “is going to be questioned. If she gives me an audience now, that questioning will take place here. If she doesn’t, it will take place before the grand jury in Madison City. You gentlemen pay your money and take your choice.”

“It’s already paid,” the butler said.

Selby started toward the front of the house. Trask came limping behind him.

“Don’t think you’re so much,” Trask said sneeringly. “You may be a big toad in a small puddle, but you’ve got a fight on your hands now. You’ll get no more cooperation out of us. And remember another thing: There’s a hell of a lot of money invested in Shirley Arden. That money buys advertising in the big metropolitan newspapers. They’re going to print our side of this thing, not yours.”

The butler said evenly, “Shut up, Trask; you’re making a damned fool of yourself.”

He handed Selby his hat and gloves; his manner became haughtily deferential as he said, “Shall I help you on with your coat, sir?”

“Yes,” Selby told him.

Selby permitted the man to adjust the coat about his neck. He leisurely drew on his gloves, and said, “The door, Jarvis.”

“Oh, certainly,” the butler remarked sarcastically, holding open the door, bowing slightly from the waist.

Selby marched across the spacious porch, down the front steps which led to the sloping walk.

XV

Selby found that he couldn’t get the developed negatives from the miniature camera until the next morning at nine o’clock. He went to a hotel, telephoned Rex Brandon and said, “I’ve uncovered a lead down here, Rex, which puts an entirely new angle on the case. George Cushing is mixed in it some way, I don’t know just how much.

“Cushing knew that the five thousand dollars came from Shirley Arden. He’s the one who warned her to change her perfume after he knew I was going to try and identify the bills from the scent which was on them.”

“You mean the money actually did come from the actress?” Rex Brandon asked.

“Yes,” Selby said wearily.

“I thought you were certain it didn’t.”

“Well, it did.”

“You mean she lied to you?”

“That’s what it amounts to.”

“You aren’t going to take that sitting down, are you?”

“I am not.”

“What else did she say?”

“Nothing.”

“Well, make her say something.”

“Unfortunately,” Selby said, “that’s something which is easier said than done. As was pointed out to me in a conversation a short time ago, we’re fighting some very powerful interests.

“In the first place, Shirley Arden’s name means a lot to the motion-picture industry, and the motion-picture industry is financed by banks controlled by men who have a lot of political influence.

“I’m absolutely without authority down here. The only way we can get Shirley Arden where she has to answer questions is to have her subpoenaed before the grand jury.”

“You’re going to do that?”

“Yes. Get a subpoena issued and get it served.”

“Will she try to avoid service?”

“Sure. Moreover, they’ll throw every legal obstacle in our way that they can. Get Bob Kentley, my deputy, to be sure that subpoena is legally airtight.”

“How about the publicity angle?”

“I’m afraid,” Selby said, “the publicity angle is something that’s entirely beyond our control. The fat’s in the fire now. The worst of it is they think that I was responsible for it. Miss Arden thinks I was trying to get some advertisement.”

“What do you mean?”

“Someone — I suppose it was Bittner — took a flashlight photograph of me dining tete-a-tete with Shirley Arden in her home.”

“That sort of puts you on a spot,” the sheriff sympathized.

“Are you telling me?” Selby asked. “Anyway, it’s absolutely ruined any possibility of cooperation at this end.”

“How about Cushing? What’ll we do with him?”

“Put the screws down on him.”

“He’s been one of our staunchest supporters.”

“I don’t give a damn what he’s been. Get hold of him and give him the works. I’m going to get those pictures in the camera developed, and then I’ll be up in the morning. In the meantime I’m going out to a show and forget that murder case.”

“Better try a burlesque, son,” the sheriff advised. “You sound sort of disillusioned. You weren’t falling for that actress, were you?”

“Go to the devil,” Selby said. “ … Say, Rex!”

“What?”

“Give Sylvia Martin the breaks on that Cushing end of the story. She’s the one who originally smelled a rat there.”

“What do you mean?”

“Talk with her. Get her ideas. They may not be so bad. I thought they were haywire when she first spilled them. Now I think she’s on the right track.”

Selby hung up the phone, took a hot bath, changed his clothes and felt better. He took in a comedy, but failed to respond to the humor of situations which sent the audience into paroxysms of mirth. There was a chilled, numb feeling in the back of his mind, the feeling of one who has had ideals shattered, who has lost confidence in a friend. Moreover, there was hanging over him that vague feeling which comes to one who wakes on a bright sunny morning, only to realize that the day holds some inevitable impending disaster.

After the show he aimlessly tramped the streets for more than an hour. Then he returned to his room.

As he opened the door and was groping for the light switch, he was filled with a vague sense of uneasiness. For a moment he couldn’t determine the source of that feeling of danger. Then he realized that the odor of cigar smoke was clinging to the room.

Selby didn’t smoke cigars. Someone who did smoke cigars was either in the room or had been in it.

Selby found the light switch, pressed it and braced himself against an attack.

There was no one in the room.

Selby entered the room, kicked the door shut behind him and made certain that it was bolted. He was on the point of barricading it with a chair, when he thought of the similar circumstances under which William Larrabie had met his death.

Feeling absurdly self-conscious, the district attorney got to his knees and peered under the bed. He saw nothing. He tried the doors to the connecting rooms and made certain they were both bolted on the inside. He opened the window and looked out. The fire escape was not near enough to furnish a means of ingress.

His baggage consisted of a single light handbag. It was on the floor where he had left it, but Selby noticed on the bedspread an oblong imprint with the dots of four round depressions in the corners.

He picked up his handbag, looked at the bottom. There were round brass studs in each corner. Carefully he fitted the bag to the impression on the bedspread. Beyond any doubt someone had placed the bag on the bed. Selby had not done so.

He opened the bag. It had been searched hurriedly. Apparently the contents had been dumped onto the bed, then thrown back helter-skelter.

Selby stood staring at it in puzzled scrutiny. Why should anyone have searched his handbag?

What object of value did he have? The search had been hasty and hurried, showing that the man who made it had been fighting against time, apparently afraid that Selby would return to the room in time to catch the caller at his task. But, not having found what he looked for, the man had overcome his fear of detection sufficiently to remain and make a thorough search of the room. That much was evident by the reek of cigar smoke.

The prowler had probably lit a cigar to steady his nerves. Then he had evidently made a thorough search, apparently looking for some object which had been concealed. Selby pulled back the bedspread.

The pillows had lost that appearance of starched symmetry which is the result of a chambermaid’s deft touch. Evidently they had been moved and replaced.

Suddenly the thought of the camera crashed home to Selby’s consciousness.

He had left the camera at the camera store, where the man had promised, in view of Selby’s explanation of his position and the possible significance of the films, to have the negatives ready by morning. Evidently that camera was, then, of far greater importance than he had originally assumed.

Selby opened the windows and transom in order to air out the cigar smoke. He undressed, got into bed and was unable to sleep. Finally, notwithstanding the fact that he felt utterly ludicrous in doing so, he arose, walked in bare feet across the carpet, picked up a straight-backed chair, dragged it to the door, and tilted it in such a way that the back was caught under the doorknob.

It was exactly similar to the manner in which the dead minister had barricaded his room on the night of the murder.

TO BE CONTINUED (READ CONCLUSION)

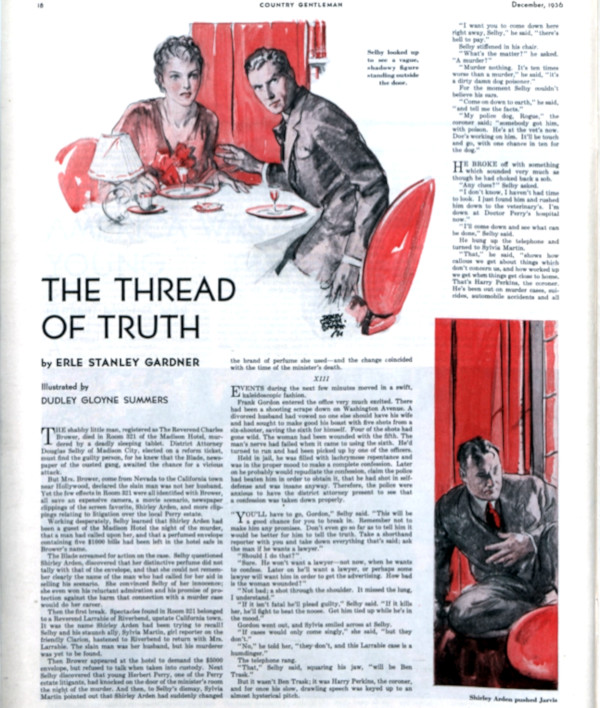

Featured image: Selby looked up to see a vague, shadowy figure standing outside the door. (Illustrated by Dudley Gloyne Summers; SEPS)