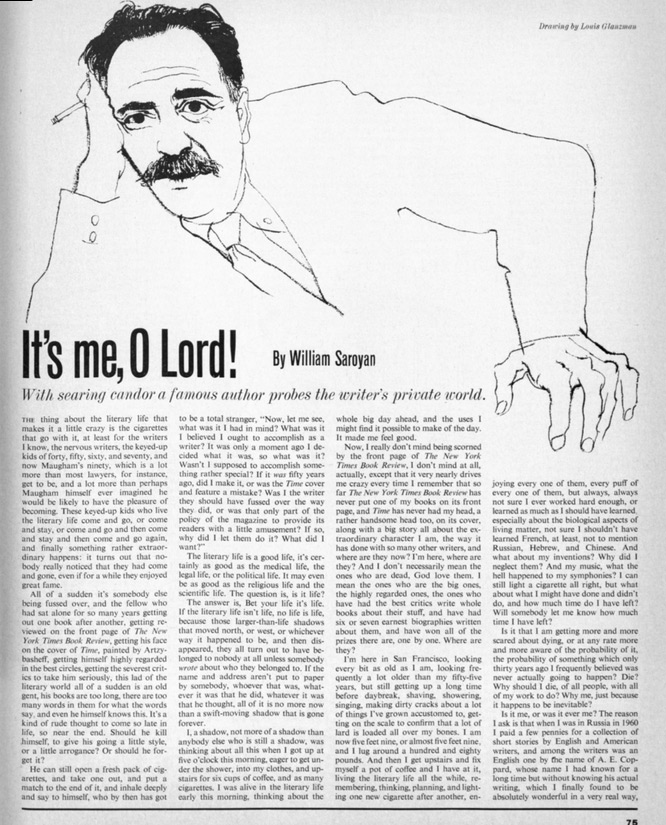

William Saroyan on Lying in Fiction and in Life

In 1964, the Post asked William Saroyan, the Armenian-American author of The Human Comedy, My Name Is Aram, and numerous other novels, to expound on his life as a professional author. “The literary life is a good life,” he writes. “It’s certainly as good as the medical life, the legal life, or the political life. It may even be as good as the religious life and the scientific life. The question is, is it life?”

In his essay “It’s Me, O Lord!” — a fantasia that follows his train of thought from cigarettes to confidence and self-doubt to the unstoppable aging of the body and of one’s body of work and ultimately to the consequences of lying in fiction and in life — Saroyan answers this question confidently. But that answer just leads to more questions, laying out the writer’s inner world of doubt.

At 55, Saroyan was a well-known, accomplished, and successful novelist, but still he was “always, always not sure I ever worked hard enough, or learned as much as I should have learned.” Readers contemplating living a literary life for themselves can find in his words either a monument to professional angst or a validation that their own doubt and second-guessing simply come with the territory.

In the end, Saroyan writes, “I don’t mind living the literary life, I live it the best way I know how.” And isn’t that the best we can expect of him, and of ourselves?

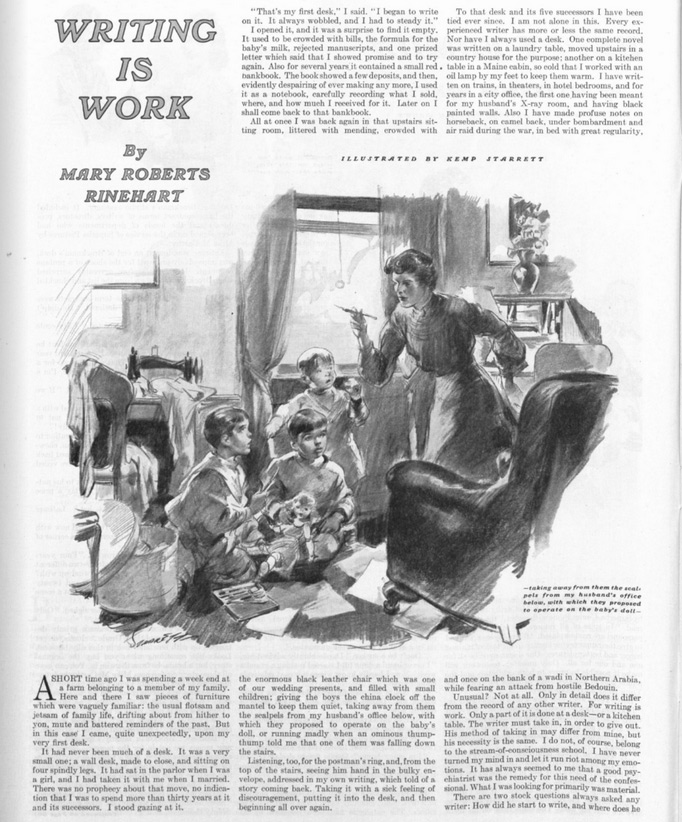

Mary Roberts Rinehart’s ‘Writing Is Work’

Each year at the start of November, thousands of writers — popular and unknown, experienced and amateur — set a goal of penning an entire 50,000-word novel in 30 days to mark National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo). Invariably, they each learn or are reminded of one simple truth: As Mary Robert Rinehart put it in 1939, “Writing is work. Only a part of it is done at a desk.”

For Rinehart, known by some as “America’s Agatha Christie” (though she was publishing mysteries for nearly a decade before Christie’s first novel), the demands of writing and rewriting on top of the responsibilities society placed upon her gender — wife, mother, cook, and housekeeper — were so rigorous that her health suffered. But even sickness could not deter her. She could not simply stop writing; it was a habit, a need, even when it made her physically ill.

Writers, according to Rinehart, “speak with loathing of their job, but few of the professionals really stop. For one thing, the early urge to write, in time, becomes the habit of writing. We are often miserable at our desks or typewriters, but not happy away from them.”

So she kept going. She kept writing: four dozen novels and plays, numerous short stories and serials — including the Tish Carberry series first published in The Saturday Evening Post — essays, and travelogues. She even served as a war correspondent for the Post during World War I. Her work earned her fame and fortune, led to her receiving an Honorary Doctorate in Literature from George Washington University in 1923, and allowed her to help her sons found the publishing house Farrar and Rinehart.

Even in success, though, she was not immune to the discouragement and self-doubt that sometimes strike authors at any level. “My own personal discouragement,” she writes, “is so keen that it reaches the point of neurosis, and I have never failed to have it. At some time during any given piece of work it overtakes me. The story seems pointless, the writing bad. I am overwhelmed by a sense of futility. I want desperately to quit, and I have a sense of actual nausea at the sight of my desk. But eventually I carry on.”

Writers who dream of a career as a novelist can find words of both encouragement and warning in Rinehart’s “Writing Is Work,” first published in the Post on March 11, 1939. Above all, though, her message is one of perseverance. Writing is not easy, but you must carry on because, ultimately, “this is writing. A world passing by, and someone with a pen or a typewriter trying to put a bit of it on paper.”

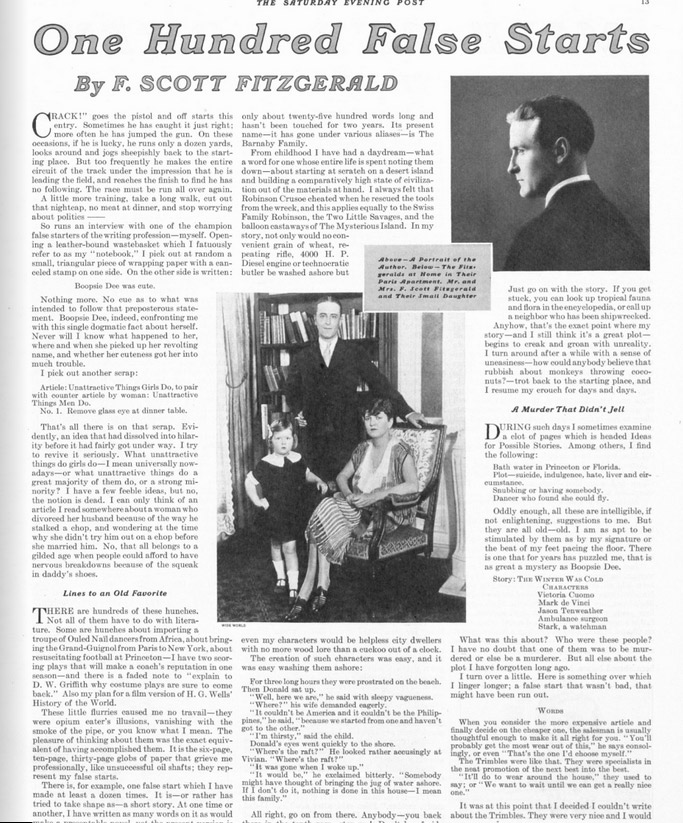

F. Scott Fitzgerald on One Hundred False Starts

For would-be and have-been novelists around the world, National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) is a time of excitement and self-discovery on one hand, but struggle and self-doubt on the other. Can I tell this story all the way through? Will people like it? Am I even telling the right story?

If you’re a writer and you find yourself struggling with your story, take heart: It happens to all authors all the time. No matter how great a writer you are, wonderful works of fiction don’t just fall from your pen.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was one of the greatest American storytellers of the 1920s and ’30s, and even his process of creating fiction was fraught with starts and stops, second-guesses, and outright failures. He writes, “It is the six-page, ten-page, thirty-page globs of paper that grieve me professionally, like unsuccessful oil shafts; they represent my false starts.”

Not getting the story right the first time is not a sign of failure as a writer. Perhaps you just haven’t dug into your experiences deeply enough to find the right story to tell. And according to Fitzgerald, your choices are actually quite limited: “Mostly, we authors must repeat ourselves — that’s the truth. We have two or three great and moving experiences in our lives … and we tell our two or three stories — each time in a new disguise — maybe ten times, maybe a hundred, as long as people will listen.”

Whether or not you agree with Fitzgerald’s estimation of the depth of a storyteller’s well of ideas, his success in the field is undeniable. On March 4, 1933, the Post published his “One Hundred False Starts,” offering readers a glimpse into how he collected story ideas and attempted — and often enough failed — to turn them into fiction he was proud of.