Post Puzzlers: January 4, 1873

Each week, we’ll bring you a series of puzzles from our archives. This set is from our January 4, 1873, issue.

Note that the puzzles and their answers reflect the spellings and culture of the era.

RIDDLER

MISCELLANEOUS ENIGMA

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

I am composed of 49 letters.

My 21, 12, 44, 32, 5, 17, was the name of the Spaniard who first discovered that America was not a portion of the Eastern Continent.

My 25, 14, 18, 11, 46, 25, 49, 45, is the name of a planet.

My 4, 28, 41, 47, 8, was the birthplace of Columbus.

My 48, 22, 10, 6, 24, 36, 48, 16, 27, 20, is the name of a city in the United States.

My 25, 40, 13, 17, 34, 31, 39, 7, 12, 29, 28, 38, was the name of a celebrated American general during the Revolutionary War.

My 11, 26, 25, 16, 19, 49, 37, 17, is the name of a high, rocky island noted as the place of exile and death of Napoleon Bonaparte.

My 34, 23, 45, 19, 33, 38, 25, 40, 11, 6, 43, 44, 31, 23, 38, was the name of a Roman king.

My 38, 29, 3, 12, 42, 27, 14, 10, 46, 16, is the name of a river in North America.

My 48, 17, 15, 9, 38, 47, 10, was the name of a President of the United States.

My 2, 23, 46, 30, 49, 34, 35, 33, 11, was the name of a celebrated Roman poet.

My whole is quite a true maxim.

Seaboard, N. C., EUGENE.

ANAGRAMS

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

NAMES OF AMERICAN CITIES

South America.

- See, a boy’s run.

- Move on tide.

- Gay Laura.

- Race Lad.

- Spare pilot.

North America.

- Hill had a pipe.

- We met Sir Ned.

- Worn key.

- Labor time.

- Try to sew.

- No more.

Seaboard, N. C., EUGENE.

CHARADE

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

My first is often found in my second;

My whole a beautiful plant is reckon’d.

Fort Totten, D. T. GAHMEW.

WORD SQUARE

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

- Part of a vessel.

- A tree.

- A female name.

- Used for music.

Fort Totten, D. T., GAHMEW.

CHARADES

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

I.

My 1st is an instrument of punishment.

My 2d is one-third of an ell.

My 3d is often seen in newly-mown meadows.

My 4th is one of the blessings of the night.

My whole is one of Scott’s characters.

II.

My 1st is a personal pronoun.

My 2d is part of the human frame.

My 3d is a product of farms.

My whole, an improving study.

III.

My 1st is a title of respect.

My 2d is part of the verb to be.

My 3d is what we do when taking our tea.

My 4th is a popular dish.

My whole is a State in the Union.

IV.

My 1st is man, expressed in a foreign tongue.

My 2d is the author of many crimes.

My 3d is something we all have but have never seen.

My 4th is a common article.

My whole is the birthplace of many great men.

PROBLEM

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

If the sides of a triangle be bisected, and perpendiculars be drawn from the points of bisection to the circumference of the circumscribed circle, they will measure 10, 34 and 98 rods, respectively. Required—the diameter of the ciroumseribed and inscribed circles, and the sides of the triangle.

An answer is requested.

E. P. NORTON, Allen, Hillsdale, Co., Mich.

ANSWERS

MISCELLANEOUS ENIGMA—Ill got gains are dearly bought, retribution soon will come.

ANAGRAMS—1. Buenos Ayres; 2. Montevideo; 3. La Guayra; 4, Caldera; 5. Petrapolis; 6. Philadelphia; 7. West Meriden; 8. New York; 9. Baltimore; 10. West Troy; 11. Monroe.

CHARADE—Shad-dock.

WORD SQUARES—

SPAR

PINE

ANNE

REED

CHARADES—1. Roderick Dhu. 1. History. 3. Mississippi. 4. Virginia.

PROBLEM—170 rods the diameter of the circumscribed circle—56 rods the diameter of the inscribed circle—90, 186 and 168 rods the sides of the triangle.

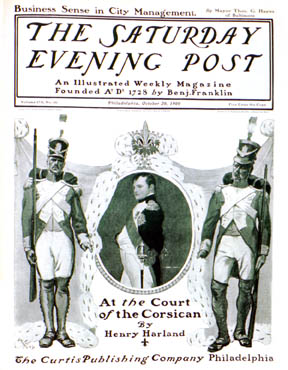

190 Years Ago: The Post Covers The Death of Napoleon

As the country’s most popular, most widely read magazine, The Saturday Evening Post became an American institution in the 20th Century. But, as our 190th birthday reflects, our history goes far back, starting 95 years before Norman Rockwell ever entered its offices.

You get a sense of how old the publication is when you consider that the biggest news story in its first issues was the death of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The death of Napoleon Bonaparte is placed beyond a doubt. News has been received from Liverpool dated July 8th. The Ex-Emperor died of a cancer in the stomach, and was buried on the 7th of May.

In that summer of 1821, the news of the ex-emperor’s death sparked many debates at dinner tables across America. Was Napoleon a liberator or a tyrant?

The Post picked up the story in August and was still running related items into October.

The illness of the ex-emperor lasted in the whole, six weeks. During the latter days of his illness he frequently conversed with his medical attendants on its nature, of which he seemed to be perfectly aware.

As he found his end approaching, he was dressed, at his request, in his uniform of Field Marshal with the boots and spurs, and placed on a camp bed, on which he was accustomed to sleep when in health.

In this dress he is said to have expired. Though Bonaparte is supposed to have suffered much, his dissolution was so calm and serene that not a sigh escaped him or an intimation to the bystanders that it was so near.

Still widely revered in France, Napoleon had many American admirers who regarded him as a champion of liberty. Most of the world hated and feared him, though. Napoleon had kept Europe at war for twelve years. His struggle for empire had cost the lives of 6 million soldiers and civilians. He had been defeated and imprisoned, but escaped and narrowly missed becoming the ruler of Europe.

Despite his past, and the destruction he caused, he seemed to enchant people. He made admirers out of most people who met him—even his enemies. Since his re-capture in 1815, journalists had been writing of his intelligence, his vision, and his destiny. Now that he was safely dead, and could never again escape from exile, it became easier, and safer, to sing his praises.

The Post quoted one particularly fawning passage from a British newspaper.

“[Napoleon’s] person was well-turned, broad in the shoulders, and, till he grew fat, very elegant downwards. The late Mr. West told us that he had never seen a handsomer leg and thigh.

His head was somewhat too large for his body, but finely cut, as we may all see in his medals. It looks like one of the handsomest Roman emperors. His face [had] a forehead of genius, and mouth and chin of resolute beauty.

Napoleon was of a warm temperament, generous and affection…. His abilities, independent of his warlike genius, were considerable. His intellect was strong and searching, and he acquired so much information that he could converse with all sorts of men on the topics which they had particularly studied.

[A Swiss historian who met Napoleon] says, “quite impartially… I must say, that the variety of his knowledge, the acuteness of his observations, the solidity of his understanding… his grand and comprehensive views filled me with astonishment, and his manner of [conversation], with love for him.”

While the Post reprinted such hero worship, it wasn’t buying any of it. The editors, being sturdy champions of the republic, viewed Napoleon dispassionately:

Thus has terminated the life of perhaps the most extraordinary man who has ever figured upon the stage of history. Born obscurely, and without evident means of advancement, he rose to supreme power, not only over France, but over the continent of Europe, and his authority was extended to both hemispheres.

Disdaining man but as the means of his own exaltation, he probably surpassed all other rulers in his ascendancy over everyone who came within the vortex of his personal influence.

After having dethroned kings and overthrown empires, he himself became the football of fortune, was dethroned and exiled to a high rock in the midst of the ocean, under the guard of the greatest powers of Europe.

There he was imprisoned, and there he has expired—a striking example of the inevitable destruction attending an uncontrollable ambition, and a warning to despots.

The Post’s editors, Messrs. Atkinson and Alexander, knew that celebrity news would sell papers. But they recognized that Napoleon Bonaparte, like most celebrities, was best admired from a distance.