8 Things You Don’t Know about “The Star-Spangled Banner”

How and why Francis Scott Key wrote the poem that would eventually become our national anthem is a well-known American legend. What is less known is that the journey from poem to anthem was long — more than a century — and fraught with controversy. Here are eight things that might surprise you about “The Star-Spangled Banner” and its divisive history:

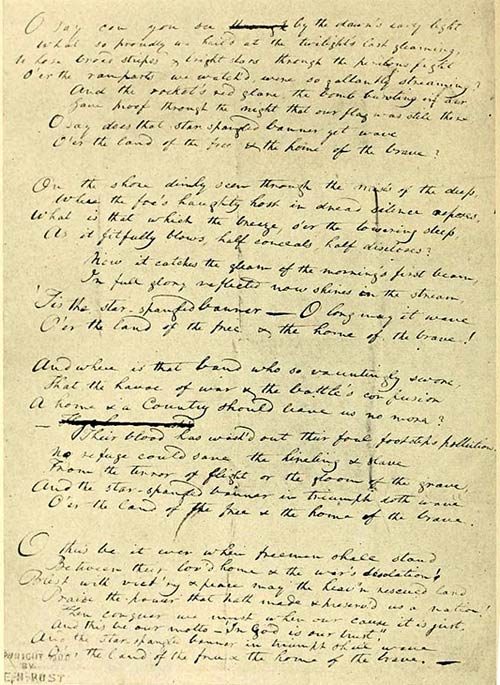

1. Francis Scott Key did not compose “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

On a list of the country’s greatest composers, you’ll find familiar names like Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and George Gershwin. Francis Scott Key will not — and should not — appear on that list. He was a lawyer and an amateur poet who, on September 14, 1814, wrote a poem called “The Defence of Fort M’Henry” while aboard a British ship during the night-long bombardment of Fort McHenry, Baltimore. Though you might say he “composed” the poem in a broad sense, he was not what is considered “a composer.” Some historians even believe he was tone deaf.

2. The tune for the national anthem is a British song about sex and drinking.

The Anacreontic Society was a gentlemen’s club of amateur musicians founded in 18th-century London and named for Anacreon, a 6th century B.C. Greek poet. Sometime in the late 1760s or early 1770s, John Stafford Smith wrote music to accompany words written by Society President Ralph Tomlinson. The result was “The Anacreontic Song,” or “To Anacreon in Heaven,” and its lyrics were no staid bastion of propriety. It ends like this (starting where “And the rockets’ red glare” is sung in the national anthem):

Voice, fiddle, and flute, no longer be mute,

I’ll lend you my name and inspire you to boot

And besides I’ll instruct you like me to entwine

The myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s vine.

Venus is the Greek goddess of love and sex, and Bacchus the god of wine. This last line is an invitation to get drunk and naughty.

Stafford’s tune was often appropriated for patriotic songs, and Francis Scott Key would have been familiar with it. It’s likely he intentionally fit the words of his “Defence of Fort M’Henry” to the tune of “The Anacreontic Song.” It quickly became the standard tune to which Key’s poem was sung, and it is now the national anthem of the United States.

3. The first word of “The Star-Spangled Banner” is not “Oh.”

Used almost exclusively in verse, the real first word of “The Star-Spangled Banner” — O — is, according to linguist Arika Okrent, a vocative O. “It indicates that someone or something is being directly addressed,” she writes, comparing it to a number of other well-known Os, including “O captain, my captain,” “O ye of little faith,” and “O Christmas tree.”

“Oh has a wider range,” she continues. “It can indicate pain, surprise, disappointment, or really any emotional state.”

And yes, it appears again in the penultimate line of the anthem: “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave …”

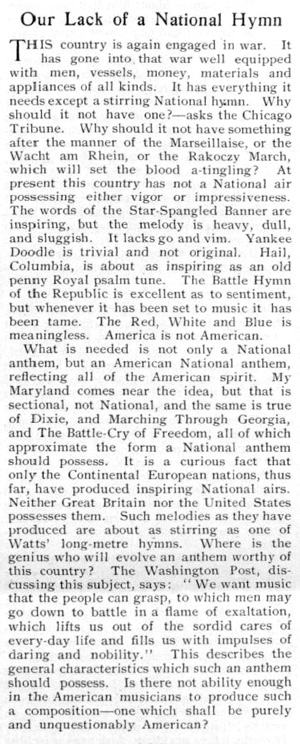

4. Many people opposed “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem.

It seems there were many reasons to dislike “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Music teachers and professional vocalists complained that the range of the song made it difficult to sing and to teach. Pacifists believed it was too violent in tone, a glorification of war. Nationalists didn’t like that the tune was of British origin. And Prohibitionists protested that our national anthem shouldn’t be what is essentially a drinking song. Other songs that were considered anthem-worthy were “America the Beautiful,” “Hail Columbia” (now the ceremonial march for the vice president), and even “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

5. The original poem had four verses and specifically mentioned slavery.

Thankfully, we don’t sing all four verses of Key’s original poem. Not only would that stretch the pregame anthem to more than six minutes, but the third verse would be a constant source of controversy. It contains the lines

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave

During the War of 1812, hirelings were black slaves hired to fight for the British military on the promise of freedom should they survive the war. Slaves and hirelings are the only people singled out for death or defeat in the poem.

Francis Scott Key, a slaveholder himself, certainly didn’t extend his vision of “the land of the free and the home of the brave” to people of color. As Jefferson Morley reports in his book about the race riots of 1835, Snow-Storm in August, Key was known to have publicly spoken about African Americans as “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community.”

6. A fifth verse appeared 47 years later.

In 1861, as the Civil War was spreading across the young country, American poet Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (father of the future Supreme Court justice) penned a fifth verse that spread widely in the north but eventually faded from the public consciousness. It, too, mentions slavery, but welcomes the “millions unchain’d” to “the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

When our land is illum’d with Liberty’s smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow at her glory,

Down, down, with the traitor that dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page of her story!

By the millions unchain’d who our birthright have gained

We will keep her bright blazon forever unstained!

And the Star-Spangled Banner in triumph shall wave

While the land of the free is the home of the brave.

According to the Library of Congress, the significance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was not lost on the Confederacy during the Civil War: Songs with names like “Farewell to the Star-Spangled Banner” and “Adieu to the Star-Spangled Banner Forever” — clearly a reference to Key’s song — were published and sung all around the South.

7. The U.S. had no official national anthem during World War I or the first eight Summer Olympic Games.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” found its first official use in 1889, when Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy directed that it be the official tune to accompany the raising of the flag by the Navy. In 1916, the year before the U.S. entered World War I, President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order stating that “The Star-Spangled Banner” should be played whenever the performance of a national anthem was appropriate.

Not until 1930 did a congressional bill to establish a national anthem find any traction. In that year, Maryland Representative John Linthicum (D) introduced a bill to make “The Star-Spangled Banner” the national anthem. President Herbert Hoover signed it into law on March 3, 1931, almost 117 years after the poem was first penned. March 3 is still celebrated as National Anthem Day in the U.S.

8. There’s still plenty of opposition to “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In July of 1976 — shortly after Independence Day in America’s bicentennial year — Texas Representative James Collins (R) introduced a bill to the House of Representatives to change the national anthem to “God Bless America.” Indiana Representative Andrew Jacobs Jr. (D) introduced not one but six separate bills to change the national anthem, one bill for each term he served between 1985 and 1996. His choice for anthem was “America the Beautiful” because not only is it easier to sing, but it also is more representative — the music was written by Samuel Augustus Ward and the words by Katharine Lee Bates, a man and a woman, both Americans.

More recently, Senator Tom Harkin (D) of Iowa took up the cause. At the end of 2014, he introduced a bill to the Senate to replace the national anthem, again with “America the Beautiful” because it “far better represents the scope and majesty of the geography of the United States of America as well as the principles of freedom, liberty, fraternity, and progress that are the unifying beliefs of our democracy.”

In each case, the bill was referred to a committee and never heard from again.

9 Songs of Uprising and Revolution

One hundred years ago today, Vladimir Lenin led the Bolsheviks in their takeover of the Russian Provisional Government. Their anthem was “L’Internationale,” a stirring song about “striking the iron while it is hot.” A catchy tune has always worked to galvanize the oppressed, wretched, and poor into action. The lyrics of revolutionary songs range from fearmongering warnings to prideful exaggerations to simple ridicule. The music varies among regions and time periods, though it often accompanies a march.

American Revolution: “Yankee Doodle”

The upbeat tune traces back to Europe, centuries before the American Revolution, but British soldiers sang “Yankee Doodle” in mockery of the colonists. The lyrics were meant to describe the foolish, classless American soldiers. However, the Yankees claimed the derisory tune as their own (and had the last laugh).

French Revolution: “La Marseillaise”

The French national anthem was written in 1792 as a rousing call to Frenchmen to fight against the Austrian invaders (“They’re coming right into your arms / To cut the throats of your sons, your women!). “La Marseillaise” gained its name from its popularity among the fédérés (volunteer soldiers) from Marseilles in the French Revolution.

Young Turk Revolution: “Mshag Panvor”

Grikor Mirzaian Suni wrote the anthem of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, “Farmer, Laborer.” The ARF was involved in the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, which led to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. The ARF went underground during Soviet control of Armenia, but since the fall of the Soviet Union the party has once again gained influence in government.

Easter Rising: “The Foggy Dew”

Canon O’Neill’s ditty, “The Foggy Dew,” was written in Ireland in 1919 about the Easter Rising, a five-day armed rebellion in Dublin in 1916. O’Neill’s tune comes from other traditional Irish folk songs, but the lyrics reflect many Irish opinions of the time that Irish soldiers leaving to fight in World War I for the British ought to have stayed home to fight for their own independence. The most popular recording of the song is by Sinéad O’Connor with The Chieftains in 1995.

Russian Revolution: “L’Internationale”

Eugène Pottier’s ubiquitous socialist hymn was the anthem of the Russian Revolution as well as the Soviet Union and many other leftist entities worldwide. Vladimir Lenin wrote in 1913: “In whatever country a class-conscious worker finds himself, wherever fate may cast him, however much he may feel himself a stranger, without language, without friends, far from his native country — he can find himself comrades and friends by the familiar refrain of the Internationale.” Pottier wrote the lyrics after the fall of the Paris Commune in 1871.

Mexican Revolution: “La Cucaracha”

The traditional Mexican folk song, “La Cucaracha,” wasn’t originally sung with lines about marijuana, but Pancho Villa’s army added in lyrics when they sang it during the Mexican Revolution. Their version of the mariachi song also contained revolution-specific lyrics about hardship and referred to President Huerta as the cockroach in question.

Cuban Revolution: “Hasta Siempre”

The “Nueva Trovo” movement in Latin America in the 1960s focused on culturally significant, authentic music as opposed to commercial projects. Carlos Puebla’s “Hasta Siempre, Comandante” was written to Che Guevara when the revolutionary departed Cuba to stoke uprisings elsewhere after the Cuban Revolution ended successfully in 1959. “We will carry on / as we followed you then / and with Fidel we say to you / ‘Until forever, Commander!’” ends Puebla’s Cuban folk song.

The Cultural Revolution: “The East is Red”

Mao Zedong disseminated a heroic image of himself in various forms of propaganda during The Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. One of them was “The East is Red,” an unofficial anthem of the People’s Republic of China during that time. The lyrics proclaim “Chairman Mao loves the people / He is our guide / to building a new China / Hurrah, lead us forward!”

Romanian Revolution: “Deșteaptă-te, române!”

“Didn’t we have enough of the blinded despotism / Whose yoke, like cattle, for centuries we have carried?” goes the Romanian national anthem, an old song called “An Echo” written during the revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire. Later titled “Wake Up, Romanian!,” the song was stripped of its national anthem status in 1947 during the country’s stint of communism, and it made a resurgence in the Romanian Revolution in 1989.

7 Game-Changing Athlete Protests

In the hyper-competitive world of high-stakes athletics, an injection of politics or social justice can inspire annoyance or rousing support; but it always starts a conversation. For over a century, these athletes have used the field, court, or track to express a broader view of how the world ought to be.

Peter O’Connor

1906 Olympics

The Irish Olympian won gold and silver medals in the 1906 games. O’Connor was registered with Great Britain since Ireland lacked an Olympic Committee. At the medals ceremony, the Union Jack was raised, so O’Connor climbed a flagpole and hoisted an Irish flag while his teammate fought off guards below. His act of resistance was likely the first time an Irish flag was seen at an international sporting event.

Taiwanese Athletes

1960 Olympics “Under Protest”

Taiwanese Olympic athletes marched into Rome’s 1960 opening ceremony behind a sign reading “UNDER PROTEST.” The team was vexed at their committee’s decision to enter the games under the island’s western name, Formosa, instead of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s preferred designation, Republic of China.

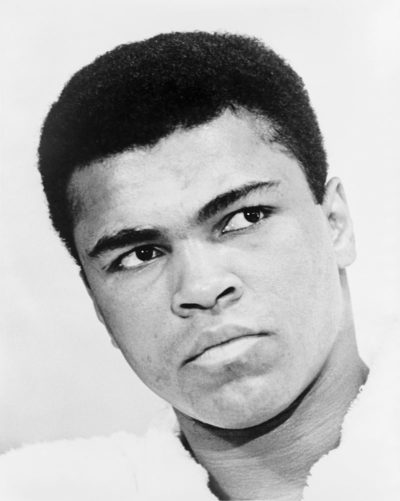

Muhammad Ali

Vietnam War, 1967

In 1967, Muhammad Ali was stripped of his world heavyweight title and had his boxing license suspended after he refused to step forward at his scheduled induction into the military. Ali said, “No, I will not go 10,000 miles from here to help murder and kill another poor people simply to continue the domination of white slave-masters over the darker people of the earth.” After an appeal to the Supreme Court, Ali’s conviction was dropped by a unanimous decision in 1971.

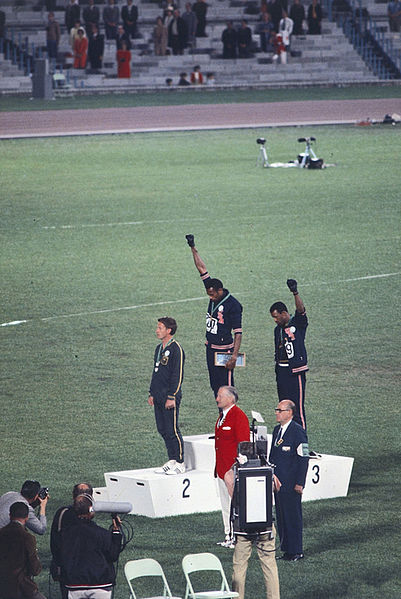

John Carlos/Tommie Smith

1968 Olympics

Mexico City’s 1968 games came in the midst of a tumultuous year for the U.S. (assassinations, Vietnam War protests, and constant racial tensions). After black athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith earned bronze and gold medals, respectively, for the 200-meter dash, they used their medals ceremony as a platform for what was perhaps the most iconic sports protest in history. As the U.S. national anthem played, the runners bowed their heads and raised their gloved fists into the air. The San Jose State University students returned from the Olympics to myriad criticism and even death threats over their gesture, perceived to be one of black power radicalism. Smith described it as “a cry for freedom and for human rights,” saying, “we had to be seen because we couldn’t be heard.”

“Black 14,” 1969

Football coach Lloyd Eaton dismissed 14 African American players from the University of Wyoming team when they asked to wear black armbands during their upcoming game against Brigham Young University. The players planned the act of solidarity after BYU students had allegedly uttered racial slurs at them in past matches. They had also learned of the Mormon policy of disallowing African Americans from priesthood. After the “Black 14” were kicked off UW’s football team, a nationwide press controversy ensued. The previously undefeated team lost its last four games in the season, and Coach Eaton was fired the next year.

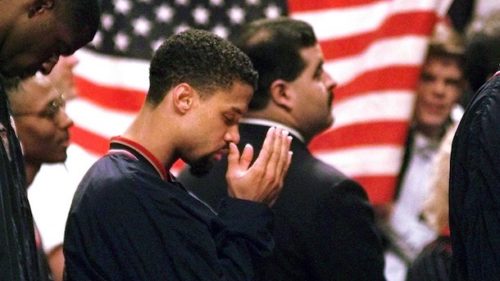

Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf

NBA, 1996

During the Denver Nuggets’ 1996 season, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, a Muslim, refused to stand for the pregame national anthem, saying, “My duty is to my creator, not to nationalistic ideology.” Abdul-Rauf was immediately suspended, but later allowed to play when he compromised that he would pray with his hands over his face while standing for the anthem. The player was booed routinely by patrons (72 percent of people in Denver disagreed with Abdul-Rauf, according to a poll). Two Denver radio deejays even faced charges for entering a mosque in Abdul-Rauf jerseys playing the national anthem with instruments as a stunt.

Carlos Delgado

God Bless America, 2004

After growing up in Puerto Rico, where the U.S. Navy used the island of Vieques as a weapons testing ground for 60 years, Toronto Blue Jay Carlos Delgado was decidedly skeptical of U.S. military occupation. After the invasion of Iraq in 2003, Delgado refused to stand for the routine seventh inning stretch rendition of “God Bless America.” His antiwar protest went largely unnoticed since he remained in the dugout during the song. Delgado saw little backlash even though the Iraq War was overwhelmingly popular among Americans at the time. It was even, apparently, popular among Canadians, since the Toronto Skydome played the song at their games until 2004.