Why You Should Get to Know the Folks Next Door

My book In the Neighborhood, published 10 years ago this spring, asked how Americans live as neighbors — and what we lose when the people next door are strangers. These questions are just as timely today. Not only is the country dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also facing a political crisis. And on top of these global and national issues, there are often painful personal matters, such as the sort of health crisis that my own family recently experienced. In each instance, neighborhoods have a critical role to play in easing adversity and averting disaster.

The inspiration to write my book came from the murder-suicide of a couple — both physicians — who lived on my suburban street in Rochester, New York. One evening the husband came home and shot and killed his wife, and then himself; their children, a boy, 11, and a girl, 12, ran screaming into the night.

What struck me — besides the tragedy — was how little it seemed to affect the neighbors. A family who had lived on our street for seven years had vanished, and yet the impact on the neighborhood seemed slight. No one, I learned, had known the family well. Few of my neighbors, I later learned, knew each other more than casually; many didn’t know even the names of those a door or two away.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters.

Do I live in a neighborhood, I asked myself, or just in a house on a street surrounded by people whose lives are entirely separate? Why, I wondered, in this age of instant and universal communication — when we can create community anywhere — do we often not know the people who live next door?

To see if I could connect with my neighbors beyond a superficial level, I asked them if I could sleep over at their houses and write about their lives on our street from inside their own homes. Somewhat to my surprise, about half the neighbors I approached said yes.

Getting to know my neighbors in this way enlivened the experience of living there. It helped me forge connections that enriched my life and made it easier for the people on my street to look out for each other.

After I told my story in the book, I heard from people all over the world about how much they missed close neighborhood ties. They also told of more recent times when they’d managed to connect with their neighbors, and how gratifying those experiences had been.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters. On the West Coast, readers recounted earthquakes and fires; in the South, hurricanes and floods; in the North, massive snowstorms. “When the power went out,” a Florida man wrote me of his neighborhood during Hurricane Andrew, “we began to cook our meals in the street. We enjoyed getting to know each other and learning each other’s stories. After a few days the power came back and we all went back inside. It’s funny, but I find myself looking forward to the next hurricane so we can catch up.”

Today, we’re all living through an unfamiliar kind of natural disaster — the coronavirus pandemic — and I see that neighbors are connecting once again. We’ve read and heard a lot of these stories, so I’ll share just one from my own family.

Just after New Year’s 2020, my 4-year-old granddaughter, my daughter’s child, was diagnosed with a rare form of childhood cancer. Suddenly, her life and the lives of her parents and 2-year-old sister were upended. What had been the happy, busy life of a growing family was now beset by fear, anger, uncertainty, trips at all hours to the hospital, increased medical bills, and two parents trying to work remotely from home.

We’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils.

My daughter’s family lives in a suburb of Washington, D.C., where the response to their 4-year-old’s health crisis was … nothing. This was not because the neighbors were unkind; it was mostly because my daughter and her husband, after living in their home for nearly four years, knew few, if any, of their neighbors well.

But the COVID-19 pandemic came just three months after my granddaughter’s diagnosis. Suddenly everyone in the neighborhood was living with fear and uncertainty, working remotely from home, and struggling with unknowns including reduced income. On a neighborhood listserv, someone offered to buy groceries and other supplies for anyone especially vulnerable to the virus.

My daughter responded:

Hi neighbors—

Some of you have offered so generously to pick up groceries for those of us who are immunosuppressed. I’m pregnant and one of my children has cancer. If anyone happens to be at a store this week selling toilet paper, tissues, or paper towels, please pick up some extra for us! Happy to pay, of course.

Thank you!

Valerie

The response was swift and strong:

My daughter will deliver items shortly (I’ll wear gloves when I put the items in the bag, so nothing will have been touched by anyone in the house).

Amy

We dropped off some tissue boxes a few mins ago.

Allison & Michael

I have a couple smaller boxes of tissues I’d be happy to drop off to you. Oh and I can give you a container of Clorox wipes too.

Betsy

I just dropped off paper towels and tissues at your front door.

Fran

And that was only the beginning. For weeks, my daughter has been finding bags of groceries and paper goods on her doorstep; in most cases, the neighbors decline payment. “Don’t be silly,” one wrote. “There will surely come a time when I need a favor from a neighbor.”

Today, my granddaughter’s treatments continue and her prognosis is good. Her family’s life is still upended, but now at least they are aided and comforted to know they live among people who know and care about them. Once again, it took a terrible event to bring neighbors together.

Can we find ways to connect with each other without a disaster?

As Americans, we have an independent streak; our impulse for freedom and self-reliance often comes more naturally than the desire for community. Social trends also work against connections. Two-career couples mean fewer people are at home or have the leisure time to interact with neighbors. Larger suburban homes — and the lots they sit on — increase physical distance. Ever-increasing hours of screen time leave us less time to socialize. And the persistent fear we call “stranger danger” steers us away from meeting others — even those who live nearby.

I’m afraid it would be naive to think that — in the absence of a new disaster — we will all just reach out to our neighbors because it’s a nice thing to do.

So, let me offer a different incentive.

Pandemic aside, this country is experiencing a crisis: Politically, we have torn ourselves in half. Whichever side you’re on, half the country thinks you’re not only wrong, but insane.

It’s a crisis that poses a threat greater than any hurricane, fire, earthquake, or pandemic. Left unchecked, I fear it can rip us in two and in the process — regardless of which side prevails — destroy the very protections we rely on for our freedom.

What is the answer? History suggests if we want to begin to repair the social fabric, a good place to start is our own neighborhoods.

Like the meetinghouses and common greens of earlier times, neighborhoods long have been the building blocks of a healthy civil society. Today, they are a place that allows us to get to know, regularly and intimately, people who may think differently than we do. With effort, we can come to know our neighbors beyond a superficial level, to know their challenges and the fullness of their lives. Once we do that, it becomes hard to mark them only with political labels.

For example, there’s a couple that lives near me. Over the years, I’ve seen them work long hours to build their own businesses — he in sales and she in consulting. I’ve come to know the two children they adopted, and for whom they’ve made a loving home. I watched as they remodeled a spare room for her mom to live in when she could no longer live alone. So I’m not inclined to dismiss my neighbors — and certainly not to think them evil or insane — merely because they’ve posted a lawn sign supporting a national candidate with whom I disagree.

“In this age of bitter partisanship and social division,” writes Ryan Streeter, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, “unity and social healing are not only possible but happening every day when we work with and rely on those who are closest to us.”

In the 2019 Survey on Community and Society, Streeter and colleagues found that most Americans get a stronger sense of community from those they’re close to, including neighbors, than from “their ethnicity or political ideology.” Moreover, they found we’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils. Seventy-three percent of us say our neighbors can be counted on to do the right thing.

So let’s not wait for the next natural or even man-made disaster to reach out to our neighbors. We have a strong enough motive: healing the bitter partisanship that infects our country.

How to get started? I think it’s just one neighbor at a time. You don’t even have to sleep over. All it takes is making a phone call, sending an email, or ringing a bell.

Peter Lovenheim is a journalist and author of six books. His 2011 book, In the Neighborhood: The Search for Community on an American Street, One Sleepover at a Time, won the First Annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize. He is Washington correspondent for the Rochester Beacon.

Originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Mount St. Helens: The Day the Earth Caught Fire

The predawn forest is dark and cold, and quiet except for the crunch of our footsteps over pine needles. Clouds of my breath reflect the light from my headlamp. Gradually, as we reach the edge of the tree line, a sharp, boulder-strewn shoulder appears, forming a diagonal through low clouds.

We’re climbing in earnest now, pulling ourselves over a maze of rocks stretching 4,500 vertical feet. The alternative — trudging up the adjacent crevasse-cracked snowfields, which fall thousands of feet toward the ground at a nearly 45-degree angle — seems horrifyingly exposed. As we inch skyward, the rising sun warms the earth and the vast, black landscape we’re crawling over.

My friend Kelsey and I had peeled ourselves from our sleeping bags in the small hours, fueled up on instant coffee and protein bars, and aimed our headlamps toward the summit of North America’s most notorious volcano, Mount St. Helens. Our 10-mile climb up the southern slope and back to our camp will take us nearly 10 hours.

“The lesson we’re taking from Mount St. Helens is that we need to be working on other volcanoes … so when they wake up, we won’t be nearly as behind the eight ball as those folks were back in 1980.”

Though physically demanding, climbing Mount St. Helens requires no advanced mountaineering equipment or knowledge, and hardy hikers who have taken adequate safety precautions and secured the necessary permits routinely claim a spot on the summit.

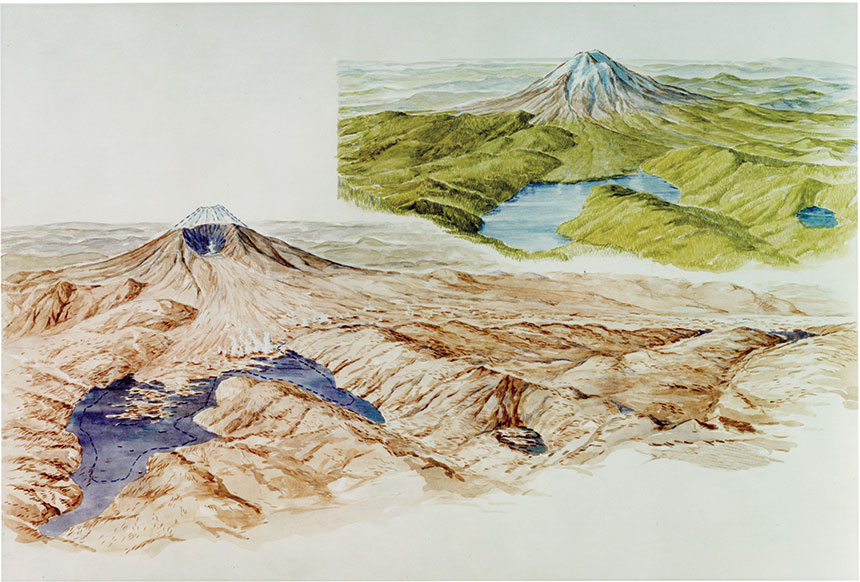

The landscape I’m scaling looked a lot different 40 years ago. In the spring of 1980, rising magma deformed the northern face of Mount St. Helens’ 9,677-foot, symmetrical cone. Things came to a head on the morning of May 18, when the bulging northern slope failed. “The whole top of the mountain slid away in the largest landslide in recorded history, and it filled this valley, as far as 12 miles away, to an average depth of 120 feet,” says Charlie Crisafulli, a U.S. Forest Service research ecologist who began studying Mount St. Helens just after the eruption.

Crisafulli likens that landslide to removing the lid of a pressure cooker; immense pressure had been building inside the mountain, which the landslide released, sending an incredibly powerful blast of lava blocks, snow, ice, and rocks outward at hundreds of miles per hour. “It leveled the trees like they were matchsticks,” Crisafulli says. “Then, beyond the extent of the toppled forest, the heat associated with the blast was enough to sear the needles of the conifer trees, killing them, but not leveling them, so you have a standing dead forest.” The devastation didn’t stop there. “It melted glaciers and ice, creating these slurries of cement-like consistency down the side of a mountain, called mudflows.”

Later came pyroclastic flows — currents of super-heated gas and rock that move at speeds of up to 450 miles per hour — laying waste to anything they touch. And rising from the newly formed crater was that volcanic signature — an 80,000-foot-tall mushroom cloud that scattered visible ash across 11 states.

All told, 57 people died in Washington State’s most infamous natural disaster — the most destructive volcanic eruption in our nation’s recorded history — that also destroyed 47 bridges, 15 miles of railways, 185 miles of roads, and some 250 homes. In the 20th century, it’s preceded only by the 1917 eruption of Lassen Peak in California. Millions of Americans alive today may remember opening their newspapers to read about Mount St. Helens’ eruption or learning about it on the evening news. Some may even recall brushing ash off their car windshields.

As an ecologist, Crisafulli’s job is to observe the widespread environmental changes taking place post-eruption. Closer to ground zero, scientists are offered a rare opportunity to study environmental renewal from “a clean slate,” as he calls it, where every living thing — from massive, ancient old-growth trees to the plants and animals they sheltered — was destroyed. Mount St. Helens offers an unparalleled opportunity, he says. “Scientists in the U.S. didn’t have experience with explosive volcanoes, so we really didn’t have a lot of understanding of what to anticipate and how to even approach our work necessarily.”

Because Mount St. Helens is so close to large population centers with major research institutes and sits on public — not private — lands, scientists were on the ground very quickly before and after the eruption, as opposed to months or years later when eruptions happen in more remote places. “The opportunity was not squandered. Within the first couple of years, there were over 200 studies established and included thousands of researchers,” Crisafulli says. “They looked at everything from molecules to the entire ecosystem. This highly skilled cadre of scientists entered the scene and collaborated to develop a remarkable long-term dataset. For 40 years, people have been studying the volcano and really trying to understand what were the initial ecological responses. How did the longer-term processes of succession and assembly of biological communities happen.”

Crisafulli and his colleagues have taken their findings to sites of other volcanic eruptions all over the globe. Their findings inform understandings of how ecosystems recover from more than just volcanic activity — they can be applied to environmental renewal after activities like clear-cut logging, mountaintop removal mining, and dam removal. “Lessons from St. Helens have helped inform how succession might occur there and how managers might go about using those lessons to get other ravaged lands back into a productive state.”

Lacking a geologist’s trained eye, I momentarily forget I’m traipsing along the back of the geophysical equivalent of a serial killer. But that fact comes into shocking focus as we ring equipment: a beefy tripod next to a large, metal box that I later learn is a GPS station, installed to measure ground surface movement, or deformation — indications that the mountain could someday wake up again. “That’s there to tell us if the surface of the volcano is changing shape at all,” says Seth Moran, the scientist-in-charge of the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory, which is tasked with researching, monitoring, and community outreach around the threats posed by the Northwest’s most famous volcano. The agency was created in the months after May 1980 to better prepare for a future eruption in Idaho, Oregon, or Washington.

The station I pass is one of two dozen scattered around Mount St. Helens, each one keeping an eye on deformations created by surging magma within the mountain. It’s all part of an early warning system designed to predict what might happen here and to better alert people living in the shadow of the volcano.

(USGS)

Before Mount St. Helens rumbled to life starting in March 1980, there was very little monitoring of the volcano — in fact, the mountain had just one monitoring station when a series of earthquakes alerted scientists that something was going on that spring. “There was a tremendous scrambling and marshaling of resources, and within a couple of weeks a pretty good-sized network was installed and operational. And that was with some luck,” Moran says, explaining that clear weather allowed good access to the mountain, and “there happened to be some equipment lying around.”

Moran adds, “It was also pretty dangerous, and people that were working on the volcano were taking a lot of risks in doing that. But there was a lot of baseline understanding of the volcano that was missed because there was not anything on the volcano really before then.”

Today’s technology, research funding, and warning procedures represent significant improvements and advancements over what was in place 40 years ago. The findings from 1980 are being applied to volcanic systems around the world, many of which pose greater dangers to surrounding communities than St. Helens ever did. For example, Moran says six volcanoes in the Cascade Range of the American Northwest are inadequately monitored today. He’s pushing for more monitoring on each of them, especially on Oregon’s Mount Hood, which, while possessing less eruptive potential than Mount St. Helens, sits closer to major population centers, posing a potentially more deadly threat. In fact, half of America’s 10 most dangerous volcanoes sit within the Cascade Range.

On Mount Hood, laws governing land use, which protect federal wilderness areas from the building of additional structures, have created regulations that prevent scientists from installing adequate monitoring stations. It’s a battle that pits scientists against environmentalists in an ongoing tug-of-war, with little indication as to how much time we have before an eruption. “The lesson we’re taking from Mount St. Helens is that we need to be working on other volcanoes to get them at least to a basic level so when they wake up, we won’t be nearly as behind the eight ball as those folks were back in 1980,” Moran says.

Our climb finally takes us beyond the boulder field, and soon we’re staring straight up toward the summit, where small puffs of steam catch a cool breeze. Improbably, in this alpine desert of barren rock, a hummingbird zips past overhead, making its way up the mountain. In the distance, the clouds cradle a view of Mount Hood’s pyramid to the south and Mount Adams to the east, two more Northwest members of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a necklace of active volcanoes arching from New Zealand to Japan to Washington State to South America.

The last 1,000 feet of the climb is an exercise in patience as we walk on ash the consistency of kitty litter. Every tedious step up is offset by a slight sinking back down, and I find I make better progress if I trudge upward without stopping for a break. I keep my eyes trained on the summit ridge.

After a final push, we’re standing at the 8,300-foot summit — no longer a smooth cone, but a jagged, semicircular rift hugged by a cornice of dirty snow. Steam, created when melting snow seeps through cracks in the rock and meets hot magma, plumes from multiple spots inside the crater. The earth here, with the planet’s great tectonic forces exposed, feels very much alive — and unsettled, a reminder that earth is governed by fire, and land is born of violence. It’s no surprise this rowdy hunk of geology earned the name Loowitlatkla, or “Lady of Fire,” from the Puyallup tribes and Lavelatla, “smoking mountain,” from the Cowlitz tribes.

Steam, created when melting snow seeps through cracks in the rock and meets hot magma, plumes from multiple spots inside the crater.

Careful not to get too close to the brittle edge, I peer into the crater incised by the 1980 blast. Within this breach sits a chaotic scene of rock and ice falls, steam, rivers of snowmelt, and hot springs. At the crater’s center sits a new dome, signaling the mountain’s regrowth as magma continues forcing its way into the mountain’s core. A newborn glacier — Crater Glacier — hides behind the south side of the dome.

This chunk of ice is significant for a few reasons: It sits at a relatively low elevation, and it’s the youngest on the continent. And in a time when climate change means most talks of glaciers are accompanied by the word receding, Crater Glacier is actually growing.

Looking north, the horseshoe-shaped crater opens toward a vast fan of scarred earth, called the Pumice Plain, with the blue waters of Spirit Lake standing out against the brown, bombed-out landscape. Scores of massive logs, once part of a magnificent old-growth forest, hug one shoreline — another reminder of the volcano’s power. Mount Rainier, the state’s tallest peak and the most glaciated mountain in the Lower 48, rises above the rumpled landscape.

It’s hard to imagine that St. Helens once bore a cone even more symmetrical than Rainier’s, and was similarly draped in massive glaciers. Rainier, too, is an active volcano, one more in a chain running from southern British Columbia to Northern California. Another sleeping giant, hovering over the Pacific Northwest, waiting its turn to unleash the most powerful natural forces on the planet.

Megan Hill contributes to AFAR, Sierra, Hemispheres, Global Traveler, among other publications. She wrote “How a Dying River Was Brought Roaring Back to Life” (March/April) about dam removal on the Elwha River in the Pacific Northwest.

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo

In the Midst of Natural Disasters, America’s True Spirit Reveals Itself

Nothing illustrates Americans’ nature better than how they response to disaster. It was proved again during the devastation in Houston wrought by Hurricane Harvey. Americans once again showed their compassion and generosity as relief aid and workers have poured in from across our national community.

It was alive back in 1900, when a Gulf hurricane ravaged the Texas coast and created the worst natural disaster in American history. On September 8, Galveston was hit by 145 mph winds and a 15-foot wave that swept over a town just eight feet above sea level. The storm left at least 8,000 dead and 3,600 homes destroyed.

Within days, help was on its way to Galveston from every state in the union. State and federal officials worked together to restore order to the city. The railway companies offered free transportation to any Galveston resident wanting to escape the city. Officials enforced price controls to make sure merchants didn’t raise prices to profit from the disaster. Volunteers worked for days tending the injured and unearthing the dead.

National unity was not particularly high in 1900. A presidential election pitting Republican incumbent William McKinley against Democrat William Jennings Bryan had raised partisan division between southern Democrats and the Republican voters in the north. But the country came together in one of the first national responses to tragedy.

In a Post editorial shortly after the hurricane, Lynn Roby Meekins observed that the one benefit of great tragedies is that they enabled the most humane and generous sides of people to emerge: “The bright lights of our national disasters are so strong that the shadows hardly show.”