Kinkers, Cons, and Canvasmen: Circus Scams Circa 1900

An anonymous con man explains how he separated men from their money in 1909.

For more on scams, please read

- Post Perspective: The Art of the Con by Maria Konnikova (from the January/February 2017 issue of the Post)

- 7 Tips for Staying Ahead of Scammers by Nicholas Gilmore

In 1909, Post reporter Will Irwin found a gambler willing to describe the con games he operated. The gambler, who remained anonymous, was generous with the details.

He described how he and a band of fellow “grafters” followed travelling circuses as they toured the country. They knew how to spot, and play, the gullible “marks” in the crowd of circus-goers. The pickings were particularly good when the circus toured small farm towns. The circus, being perhaps the only professional entertainment the farm families saw all year, drew customers from miles away. And farmers made easy targets.

The nameless gambler here describes several of the games used: the “cloth,” the “roll-out,” and, of course, the shell game.

The gambler admits that the games, when described, seem so obviously rigged that even the most ingenuous country boy could have seen through them. But “natural greed” blinds the victims to the scam “until his eagerness for big money kills his common-sense.”

While it took a calm head and a steady hand to cheat people with cards, dice, and peas under a shell, eluding the consequences was more challenging. A grafter acting as the “fixer” would visit the local guardians of morality — sheriff, justice of the peace, or judge, even an accommodating mayor — and bribe them for permission to run con games in their town, usually for the price of a few circus tickets.

The real test was not mastering the trick of a rigged game, though. It was finding the cunning, muscle, and quick reflexes to avoid the consequences when a sucker realized he’d been cheated.

The Confessions of a Con Man: Life with the Old-Time Circus

March 6, 1909

This circus was a little nine-car concern which had some territory in Indiana and Michigan — we cut a zigzag course all the season. We showed a few poor trapeze and bareback turns, a small menagerie, and some clowns.

It is an axiom in the circus business that first-class ring acts don’t pay in the country. When you strike the cities you find them more critical. Farm people care mainly for the menagerie. A circus is always divided into two camps, the performers — we call them “kinkers” — and the gamblers. The kinkers are the most retiring and exclusive people in the world. Half of them can’t tell you the name of the town they’re playing. They don’t seem to have any interest in anything but their acts. They go to their bunks when the performance is over, get up next morning at the stop, practice, do their turns, eat, and back to the bunks again. They hate the grafters on principle, because the gambling games make so much noise and trouble. The canvasmen, as a rule, side with the grafters.

We had two shell games, a “cloth” and a “roll-out” team. I don’t have to explain the shell game, I guess.

“Cloth” is an easy-money dice game. The operator has before him a sheet of green felt, marked off into figured squares—eight to forty-eight. The player throws eight dice, and the dealer compares the sum of the spots he has thrown with the numbers on the cloth. Certain spaces are marked for prizes, five or six are marked ” conditional,” and one, number twenty-three, is marked “lose.” The dealer keeps his stack of coins over the twenty-three space, so that it isn’t noticed until the time to show it.

These spaces marked “conditional” are used in a great many gambling games, such as spindle; they’re the most useful thing in the world for leading the sucker on. For when he throws “conditional,” the dealer tells him that he is in great luck. He has thrown better than a winning number. He has only to double his bet, and on the next throw he will get four times the indicated prize, or, if he throws a blank number, the equivalent of his money. He is kept throwing “conditionals” until his whole pile is down; and then made to throw twenty-three — the space which he failed to notice, and which is marked “lose.”

You may ask how the dealer makes the sucker throw just what he wants. Simplest thing in the world. The man is counted out. The table is crowded with boosters, all jostling and reaching for the box, eager to play. The assistant dealer grabs up the dice, adds them hurriedly, announces the number that he wants to announce, and sweeps them back into the box. If the sucker kicks, a booster reaches over next time the dice are counted, says “my play,” and musses them up. The player never knows what he has thrown.

“Roll-out” has many variations. The operator stands in a buggy, spieling for a new line of licorice candy. He announces that, in order to introduce the goods, he is going to take an extraordinary measure. He is going to wrap up a twenty-dollar bill in one of the packages and sell it at a reduced figure to a gentleman in the audience. After a little bidding, a booster buys it for fifteen or sixteen dollars and shows his twenty-dollar bill to the crowd. This pulls on the sucker, who has been marked and felt out from the moment that he arrived on the grounds. When he buys his twenty-dollar bill — maybe it is fifty or a hundred if he looks good for it — he finds only a dollar bill in the package — a sleight-of-hand trick does the work.

Doesn’t it sound foolish for me to sit here and tell you that people are roped into such a play as that? But if I could tell the whole story of one of these swindles, put in the dialogue, the little gestures and stage business, you would see how gradually his natural greed is brought out in the sucker until his eagerness for big money kills his common-sense. Human greed is the best booster of the confidence man.

In my time with this show I saw the rise and development of one of the greatest American gamblers. I call him Big Blackey, which is near to his name. When I joined he was just an ignorant canvasman from the West Virginia mountains. I used to see him hanging around the shell games—a great, big, raw-boned fellow, with a face a good deal like Lincoln’s. He watched the shells until he saw how they did it, borrowed some apparatus, and learned to be a good manipulator. By the end of the season we had him regularly at work.

Really, there isn’t a lot in manipulating shells. The “pea” is a little ball of very soft rubber, like the composition they use in printing rollers. It is so squashy that when pressed it becomes as thin as paper. The manipulator never has to lift his shell at all. He simply catches the pea under the edge of the shell, and rubs until it pops out under his hand. He picks up the pea between two of his fingers and holds it there until he is ready to roll it back—under the wrong shell. It was in understanding suckers and handling men that Blackey shone. That big, fishy eye of his saw the soft one the minute he stepped into the crowd. When Blackey had his man spotted he used all his boosters and tappers to the very best advantage — even in the first season I used to stand around and watch him, as an education in keeping things going. He had plenty of nerve and could fight with the best of us when there was any trouble. But he kept out of trouble all he could—he was strictly business, that Blackey.

I got my first real experience as fixer that year, and I learned a lot about stalling. When the show struck town I saw the chief of police first — he was generally easy. I have bribed them with tickets alone. Next I fixed the justices of the peace, and once in a while I attended to the mayor. Ten or twenty dollars apiece would usually satisfy the officials of a small town. I’d explain carefully that we didn’t intend to take away big Money from any one. All we wanted was permission to run a few legitimate games of chance. There should be a little license allowed on circus day.

Mayors that I couldn’t buy I worked in another fashion. I could always give them free tickets for themselves and families. When the mayor’s party arrived my assistant would take them in hand, and keep them entertained about the big top until supper-time.

The town authorities, no matter how heavily they were bribed, seldom let the shows run all day. Generally, some skinned sucker would put up such a kick that the authorities would awake to the nature of our harmless little games, and close us out. I’d stall the police as long as I could; when I reached the end of my devices I would let them arrest a dealer or two. In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the prisoners would be taken before one of my bribed justices and let off with a little fine, which came out of the “nut.” On account of this danger we started the games as soon as the parade began, threw in a lot of boosters, and kept things going at top speed. If we had taken in a thousand or twelve hundred dollars before the police came down on us, we were satisfied.

The hardest part of my job, though, was stalling the weeping suckers who came around to demand their money back. My methods varied with the man. In the case of a big, blustering, cowardly fellow, a straight, swift punch in the jaw was sometimes the best medicine. If he got me arrested for it I could always bring witnesses to show that he had started a disturbance and threatened me. Sometimes I would laugh at my man, telling him that he got what he might expect. Sometimes I’d sympathize, promise on behalf of the management that the affair would be looked into. I learned one thing early — never give anything back unless you give it all back. For if you do return a part it proves the weakness of your position, and the’ sucker howls harder than ever for the rest. Moreover, the other suckers hear about it, and you have to settle with them all. On one occasion I had to hand over a roll of three hundred and fifty dollars which we had taken at the shells. The sucker, it turned out, was brother-in-law of the chief of police; and though the chief was bribed, it didn’t prevent him from threatening to arrest the whole outfit unless we gave up.

As we struck into the Michigan woods we began to come against the French-Canadian lumbermen — soft but troublesome. When they lost they always wanted to fight. They were big, strong chaps, but their methods were unscientific—mostly wrestling and clawing the air. Scraps became more and more common around the show. We made so much noise at night, settling up with the day’s picking, that the kinkers threatened to quit. The farther north we went the more troublesome they got. It culminated in a border town of Michigan — Oscoda, I think. We had put in a great day. I had the officials sewed up, and the games went on until late at night. In the early afternoon we caught a big lumberman, who seemed to be a kind of leader, for seventy-five dollars at “roll-out.” He raged up and down, trying to stop the circus. The canvasmen threw him out of the lot. His mates ran up to help him. I scraped my way through the mob and got to the leader. Instead of listening to me, he came at me with his arms flying. I let him have it in the jaw. I don’t know what might have happened if the town police hadn’t broken up the mob.

I thought the police would close us out right there; but they were too well fixed. Nevertheless, I saw trouble; and I went from game to game advising the boys to go easy. The money was rolling in like water, and they only said, “Let ’em come on.”

“All right,” said I; “they will.”

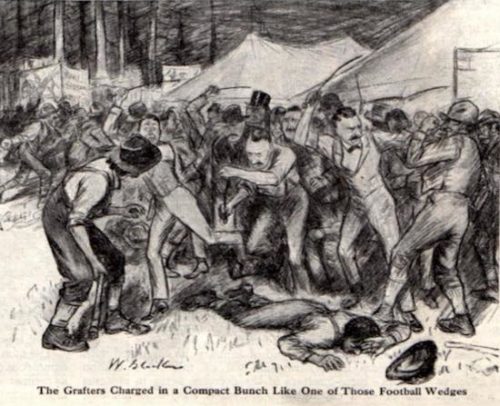

At half-past eight, with the performance going on inside and the games still drawing in the side-show tents, I heard that “zaa-zaa” sound of a mob. I ran to the corner of the lot. About two hundred men in their shirt sleeves were approaching in a bunch. It appears that a little Frenchman, who had been done out of fifty in the shell game, had gone down to their hang-out and aroused his mates. They were coming to lick the circus.

I ran toward the side-shows, yelling “Laying-out pins!” at the top of my voice. That call always brings the grafters out for a fight. A laying-out pin is a thin iron stake which the boss canvasman uses to mark out the tent space; it is a great weapon in a fight—just heavy enough to lay a man out, and just light enough to bend over his head without breaking his skull.

The grafters, about twenty-five in all, jumped to their pins and gathered in front of the big tent. The French-Canadians stopped at the corner of the lot, howling and yelling. I said, “Boys, if they come in a bunch, beat them to it.” I knew that if the fight came off close to the tent we stood to lose good canvas, besides making a panic inside.

And all at once the Frenchmen rushed at us in a long line.

“Now,” said I. The grafters charged in a compact bunch like one of those football wedges. They hit the mob right in its center, and went through. I didn’t have time to see what happened next, for I found my own hands full. I had stayed back, like a general, to direct things. Well, when our fellows went through, the end of the line kept on, and a few stragglers reached the big tent. They were about crazy with excitement, and they seemed to have some idea of wrecking the show. Three of them grabbed

the stake-ropes and began to pull. I came up from behind and let the nearest one have it with my laying-out pin. The others dropped the ropes and came at me separately.

I got the leader with a punch in the pit of the stomach — quarters were too close for the pin. The canvasmen attended to the other fellow. When I had time to look around the Frenchmen were flying in every direction, with the grafters chasing them in bunches of three or four. It appears that our wedge had gone clear through the line. Before the enemy could form again our fellows had turned back and charged through them in the opposite direction, taking some of them in the rear. That finished them; they just turned and beat it.

We carted off seven Frenchmen to the hospital. I don’t know that any of them were disabled for life, but some looked to be pretty badly hurt. Besides a few bruises and cut heads, the only injury we had was one broken arm.

Featured image: All illustrations from “The Confessions of a Con Man” by Will Irwin from the March 6, 1909, issue of The Saturday Evening Post