A Millennial Leaves His Phone and Goes into the Woods

On normal mornings, I wake up and immediately grasp my cell phone from its resting spot next to my pillow and Google the previous day’s new Coronavirus cases. At least, that’s how it’s been for the past few months. But when I woke up last weekend, there was no frightening uphill chart to behold, because there was no phone. I rolled over and gazed out at a blur of treetops through a tent screen. I put on my glasses and realized I was looking over a foggy valley, that the camping spot I had stumbled onto late the night before sat on a cliff perfectly situated to receive the sunrise.

When I decided that I would leave my phone behind to disappear into southern Illinois’s Shawnee National Forest for the weekend, my roommate was concerned. “Why would you do that?” she asked. “What if you get lost?” I told her that people don’t get lost in America in 2020. “That’s because they have cell phones!” she countered.

I would hesitate to claim I have smartphone addiction, but I’ve been known to pass hours slumped on the couch, scrolling through yoga videos I might one day try, bruschetta recipes I might make, far-flung destinations I might visit. I’ve lingered a little too long on Twitter during work hours (don’t tell my editor), and there was that one blur of a weekend that was entirely lost to the engrossing Bloons Tower Defense 6 game.

Of course, I’m not alone in my tendency to zone out and fall headfirst into the time-consuming trappings of the device. According to several surveys from 2017, Americans, on average, spend from three to five hours each day on mobile devices. For younger people, the number is even higher. Our collective panic over wasting time on our phones has created space for some savvy panaceas in the private sector. Tech rehabs have cropped up, self-help texts for more mindful phone use abound, and Google has even gotten in on the action with their launch of Digital Wellbeing. The app gives users a rundown of their screen time and offers nanny-style blockers from too much browsing and scrolling.

I wasn’t seeking such a formal tech break, though; I only wanted to test out the cold turkey method for a weekend. So I dug out my backpacking gear from the back of my closet, gathered a few books (Birds of America by Lorrie Moore and Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill), and prepared to realize some long-held plans to visit a jewel of the Midwest: the Garden of the Gods Wilderness. I told my dog Calliope where we were going, and she seemed indifferent.

My loved ones insisted that I at least keep my phone in the car. I could stash it away and keep it turned off, they said, as it could be necessary for an emergency. I was travelling four hours away to an unfamiliar area, and my Prius did have about 550,000 miles on it. I might have something to prove, I thought, but I’m not stupid. I resolved to hiding it in the trunk.

What would it be like, I wondered as I followed my handwritten directions across hilly southern Indiana, to spend a few days with only my thoughts and my dog? On a local radio station, the deejay gave a shout-out to her “Facebook friend of the week” and directed listeners to her page to check out a video she’d posted of a cute animal. I lucked out and found an Ella Fitzgerald CD in the glove box left by the previous owner.

The Shawnee National Forest, stretching across southern Illinois between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, covers almost 300,000 acres. The sandstone cliffs, bluffs, and hoodoos of the Garden of the Gods were created more than 300 million years ago when the region sat on the north shore of an enormous sea. The continental glaciers that carved much of the state into flatlands stopped just short of the Shawnee Hills, allowing these ancient structures to remain intact and providing views unlike anywhere else in the Midwest.

There is also plenty of wildlife — both dangerous and benign — to be found in the forest. Box turtles, raccoons, opossums, hawks, vultures, and squirrels are everywhere. With some bad luck, you might stumble onto a cottonmouth, copperhead, or even one of the elusive rattlesnakes, the timber rattler or the massasauga (all the more reason to refrain from hiking-while-texting). There are black widow and brown recluse spiders as well as the velvet wasp, a wingless ant-looking bug that delivers “the most painful insect sting in the world.” Encountering any of these spine-tingling creatures is fairly rare, however, and dying from any of them is all but unheard of. That’s what I told myself as I marched through the woods in the middle of the night, my flashlight casting quick, darting shadows on the vast expanses of poison ivy.

Since Shawnee is a national forest, it’s free to camp anywhere you’d like, as long as you maintain some distance from trails and waterways. You can often find unofficial campsites where others have constructed stone fire rings and makeshift seating. On the second night, Calliope and I stumbled upon such a spot, and I built a fire to cook ramen while she collapsed nearby and stared at me thinking, what in the hell are we doing here?

What were we doing there?

I had scratched the long-disquieting itch to get away from it all, but at first it seemed I had traded isolation in my home for isolation in the woods. Camping alone, or with a furry friend, is a surefire way to strip down the distractions of daily life and spend time thinking about where you are and where you’d like to be, both literally and metaphysically. Going without a phone is akin to constant meditation, at once trapped with your own thoughts and liberated from the fast lane of the information superhighway.

There has been some research into the effects of “problematic smartphone use”— particularly as it applies to young people and social media. We know that poor emotional well-being and smartphone overuse are often connected, but causation is difficult to prove. A study released this year in Cyberpsychology looked at “FoMO” (fear of missing out) and PSU (problematic smartphone use) as two separate but connected factors affecting emotional well-being. The findings suggest that it can be a sort of a vicious cycle, with negative feelings arising from both “FoMO stimulating online relationships at the cost of offline interactions and physical symptoms associated with excessive smartphone use.”

The study, along with many others, lends credence to something many of us innately understand: when I waste too much time on my phone I feel bad afterwards, and when I feel bad, I retreat to the comfortable, familiar habit of slingshotting angry birds and scrolling through my ex’s gym selfies.

Without a phone, I noticed more of the world going on around me, like the yellow butterfly that landed squarely on my dog’s nose and stayed, flexing its wings, until she shook it off. I noticed the complete silence that overtakes the woods at dusk. It comes right after the birds’ chirping has tapered off and right before the crickets and katydids begin their nighttime cacophony of sounds. I sat and listened, feeling still alone but also incredibly peaceful — the kind of feeling I might be able to define perfectly by whipping out my phone and Googling an antonym for “stress.” The forest offers this to anyone willing to turn off and tune in to the natural world.

Could there be a way to experience this kind of quiet and focus without hiking for hours and pumping creek water through a charcoal filter?

On Sunday, I slept in to some unknowable hour and then packed up my things, planning to make the trek straight back to the car and drive immediately to the nearest store for a sugary canned coffee drink. Calliope and I set off, making our way through the trails we had hiked in on. When we came to a familiar four-way intersection, I consulted the map and continued on a trail that, I was 90 percent certain, would take us back to the car.

After an hour of hiking deeper and deeper into the woods, I realized we were on the wrong trail. It curved around in a disorienting fashion, and led to a steep uphill climb that I distinctly did not recall from the hike in. Then we found ourselves climbing uphill even more, and yet again. Turning around the bend of every curve brought the excruciating sight of more ascending trail. How high could we possibly be going? I thought. It’s Illinois!

Then, we turned a new corner to find a clearing. Approaching it, I saw that it overlooked the valley in which I’d spent the past few days camping. It had to be the highest point in the park, with a view of the forest and even the farmland past it for miles. The dog walked right up to the edge and looked over, and I realized that I hadn’t known for years whether she was afraid of heights because I hadn’t taken her to any cliffs before. She stood proudly before her domain, creating the perfect opportunity for an adorable (hypothetical) Instagram picture. There would be no evidence on social media of the trip: no livetweeting, no 360-degree videos, no deluge of Facebook likes from jealous friends. The whole thing would have to be archived in my own mind.

When we finally found our way back, we were practically crawling to the doors of the Prius. Driving home, I reflected on the merits of “unplugging,” and what exactly the big takeaway could be from such a short vacation from tech. Would I arrive home and immediately revert to my old ways of binge-reading Twitter drama and feeling phantom phone vibrations on my left thigh every 10 minutes? Would I even remember this vacation if I couldn’t be reminded of the beauty of the Garden of the Gods by Facebook Memories in years to come?

What I will remember is the noticeably heightened sense of focus and peace I felt in the woods. If you give up the smartphone for a few days, you might become hyper aware of just how long it has been since you lived without one. But realizing that it is possible can inspire you to take more breaks from your smartphone day to day. Leave it at home and go on a long walk, or pledge to trim down your notifications. You might be surprised by how much you notice when you aren’t always grasping for your phone. And we could all use more pleasant surprises.

Featured image: Shutterstock, by Oleksandr Koretskyi and A-spring

“Bear Knob” by Will Levington Comfort and Zamin Ki Dost

Will Levington Comfort became a war correspondent after serving in the Spanish-American War, paving the way to a career as an adventure writer. Willimina Leonora Armstrong, under the pen name Zamin Ki Dost, wrote poems and stories about India after spending time there as a medical missionary at the end of the 19th century. The paralyzed Armstrong penned her stories with the help of Comfort. Their short story “Bear Knob” depicts two rangers in an Indian forest investigating a supposedly dangerous family of bears.

Published on January 10, 1920

Carver, the young Englishman of the forest reserve, whose experience with the deadly karait has been told, was returned by his department to the mountain station above Carlin’s bungalow near Murree. He was given a native deputy, who occupied Beattie’s little cabin across the summit. Carver was rather slow rounding-to after the tragedy and had been permitted for several weeks to remain below for weekends at the Deal bungalow. Skag’s work among the wild animals had become intensely interesting to him. It had been the wedge of their acquaintance on the top rock that first day when they discussed the little venomed one together. The Englishman had never particularly developed his latent knowledge of animal lore, but unquestionably had a way with the little creatures which fascinated the American more than any hunter’s prowess. Skag walked up the path one early morning and joined Carver at the karait’s rock before it was warmed in the sun.

“The little beggars took themselves off after Beattie and their mother had it out together,” Carver explained.

He spoke lightly enough, but the death of his senior officer had dug into the very center of his vitality, so that it was almost a miracle that he fully regained his faculties again. Even now he had a way of looking off into the distance when left alone too long that had warned Carlin of his need for companionship. So Skag stood by closely but unobtrusively, joining him up at the station at least one day in the midweek.

“And you haven’t seen the baby karaits since the mother left them?” he was saying.

“Not a wiggle.”

“And what about the rest of the outfit?”

“You mean her mate?” Carver asked.

“Yes.”

“Never was here,” Carver remarked. “Away on foreign business. Off and on for eighteen months I saw her. Twice she hatched a handful of little blue eggs, and presently you’d see the young fiends following her round. She would open her throat for them to leap into if I went too near. But I never saw their father:”

For a long time, the two men looked away across the valley to the slopes of the great mountain that commanded the eye from almost any position in Murree and vicinity. The midslopes were mainly a tight weave of green, broken by occasional great forest trees. The crags began farther toward the summit.

Carver spoke:

“If you watch long enough you will see bear — black bear — in that big brown patch where the grade is easy.”

He pointed across the valley to a spot on the great mountain slightly below their present eminence. The easy grade that he spoke of was like a big knob on the mountain side.

Its upper surface looked as if it had been burned or trampled recently.

Skag settled himself comfortably, as if to say his fault was rarely in not looking long enough for an object, but Carver observed that it was his experience that the bears only appeared afternoons.

“How far is it over there to the knob?” the American asked.

“Nine or ten miles airline.”

“And the paths?”

“We keep them open after a fashion. I’m supposed to ride over there once a fortnight.”

“A full day’s ride?” Skag questioned.

“Yes, and another to get back,” Carver replied.

“You say a horse can handle himself up and beyond the bear knob?”

The other nodded.

“I’m expecting a horse in a few days. Ian Deal has an Arab he wants me to use. We’re staying in Murree three months longer. I never really got acquainted with bears — even in captivity.”

Carver relished the possibility of an excursion and set himself to prevent Skag’s interest suffering from neglect.

“That knob has been the summer place for one family of bears for a generation, according to the natives. They say that the old sire is losing his morals — that the mother can’t live with him in cub time. For three or four seasons, the natives say, there have been two young in the family — then presently one is missing. The old girl has managed to raise only one for three seasons.”

“Does the male destroy the other one?”

“Evidence circumstantial.” Carver said whimsically. “I’m telling you how it looks to the natives and from this distance across the valley. I’m their nearest white neighbor, you understand.”

“The mother must have her work pretty well cut out to save one cub, if the old one is really ugly.”

“A native young man studying for the Christian ministry informed me seriously that the father bear was an unnatural parent. We really need to look into the matter.”

They watched the distant knob for a long time as they talked without a movement being noted there. Skag started down the path toward Murree, saying: “A real investigation calls for a close-up anyway. But tell me, could one use a dog on a trip like this?”

“An objectionable dog,” Carver answered. “Certainly not Nels.”

“Why?”

“No dog would stand a show with a full-grown black bear of the Hills. I’d hate to see a man-dog like Nels hugged to death by a cub-killer.”

Among the various things to ride on the face of the earth, Skag had tried many. He had done real camel service — days of travel from dawn to dusk, days that forgot themselves in more days. You don’t know what a camel is from a ride or two. Everything in a man, even the structure of his being, hates and cries out against the camel-thing in a period between the first few sittings, while the novelty lasts, and the real adjustment which requires weeks of caravan life. A man has to be born again, at least to be made over on the outside, to strike the rhythm for a long caravan stretch. The camel smell dies out from sheer familiarity; camel sounds cease to be heard because they have worn the delicacy off the eardrum through repetition. A sort of soft insanity takes the body and mind of a white man before he is camel-broke. Nothing in reason could ever give to the lurch or parry the pitch of the camel stride.

And Skag had been present on a racing elephant. It is hard to urge the usual captive hathi up into his real speed, but in certain cases it can be done. Gunpath Rao had actually run with Skag in his howdah. It had taken the marvelous young prince of the Hurdah stockades nearly twenty-four hours to get his gears to high speed, but in that final rousing the result was so fast that anything but an elephant or a locomotive would have left the ground for more than safety intervals. The tendency is markedly to rise in velocity like that.

Days with the circus had not permitted Skag to miss many experiences in the way of sitting creatures even partially designed to carry men and boys — mules, llamas, zebras, even a boy-loving old bull moose. And yet one of the real external joys of his life was to step into the saddle of the black Arab Ian Deal had sent.

In that first half hour in the mountains he knew what riding really meant. The Arab squared his shoulders when warmed to full trot on a straight stretch of road, arched his neck and folded up and under his front hoofs with a rhythm and power that filled the man with exultation and broke a seal somewhere in his chest, letting in more life.

Three or four miles away on the rolling roads he had a clearer sense than ever before what life meant — the joy of it — of what life might be made, and the great pulsing zest of physical well-being. The heat and magnetism surged up to him from under the saddle and from the mane and shoulders. It was like the dance. He knew that the mount loved it as he did and was changing great drafts of cool mountain air into bridled action but unbridled joy.

“I have ridden always,” he told Carlin as he came out from the bath a little later — “ridden many mounts not half so bad, but I never quite knew what a horse could be until today. Why, Carlin, I couldn’t let the groom take care of him when we came in. I had to rub him down myself, and this Arab prince seemed aware that it was a privilege.”

She sat down, not laughing aloud, but smiling as if trying to hold him in his present joy and not break in upon further words.

He was riding with Carver along the narrow, tangled, winding paths on the way up toward bear knob. They carried blanket rolls, saddlebags well stocked and grain for a sparse three days’ feeding. The grade was easier than it appeared from the lesser summit across the valley. There were aisles between the great deodars where the shade was so dense that there was little or no small growth below. They would halt from the sheer joy of the silence and say nothing to each other, after the manner of men; halt in that cathedral dimness until the spell was broken by a bird song, every vibration of every note clear as an etching. In one of these colonnades of majestic trees Carver stopped at length.

“There’s no better place for a camp than this,” he said. “The bear knob is directly above. We can’t leave the horses any nearer their premises.”

“You spoke of a spring,” Skag said.

“Just a little ahead in a tangle of vines. We’re near enough with the horses. You see, the bears come down to drink.”

They picketed, then did some steep bits of climbing among the crags to reach the knob. That which had looked like a tiny kitchen garden from across the valley was now before their eyes, a sunburned, semi-open stretch of several acres. Rock was very close to the surface, many boulders jutting through. Trees were sparse and low because of the shallow soil. Thickets and berry bushes skirted the edges of the open area, and among the great rock piles in the center were many possibilities for natural dens.

After three hours in a screened thicket that commanded the main surface of the knob, Carver slowly reached for his right ankle and drew it out from under him, using both hands. He placed the long leg straight on the ground in front and went after the other. With pained face he waited for the blood to flow into the sleeping members. Then he drew out his watch and held it to Skag, pointing with impressive finger at the hours that had passed.

Skag smiled. The sunlight was in and through him. His eyelids were lowered a trifle sleepily, but that hardly expressed the look of them. The eyes themselves were different — their look somehow out of physical focus, the pupil dilated slightly, as if centered upon a film or shadow too faint for the optic nerve quite to delineate. Carver had changed his position twenty times; Skag not more than once an hour. Moreover, he had not been conscious of strain, and Carver was exhausted.

“You can have ’em,” he whispered monotonously. “Why, I’d rather have a stroll down on the mountainside than a whole pageant of bears! I’d rather have a cigarette than a three-ringed circus of assorted bears. Also I need tea — strong, red, unboiled tea, made of soft spring water — more than any essential knowledge or revelation about High Hill bears.”

Skag held his smile. The other slid himself back out of sight.

Creatures of the wild move in mysterious ways. It was past midafternoon and fully an hour after Carver left before the den of rocks gave forth any life. There was a moment when a certain shadowed entrance was empty, and the next it was filled. There was a field of sun glare between Skag’s eyes and the blotch of shadow which had become darker and was now taking form.

The old dame was standing there. Skag’s mind must have rejected the image at first because of the long waiting. But certainly she was standing there now in thin faded coat and full late-summer fatness. Then she sat. It was easy for her. She quietly rolled back like a rag doll with a head of cotton stuffing and a body which concealed a billiard ball. She didn’t even rock, but the little chap had to roll over and shake himself to be sure he was all out of the den after squeezing past her in the doorway.

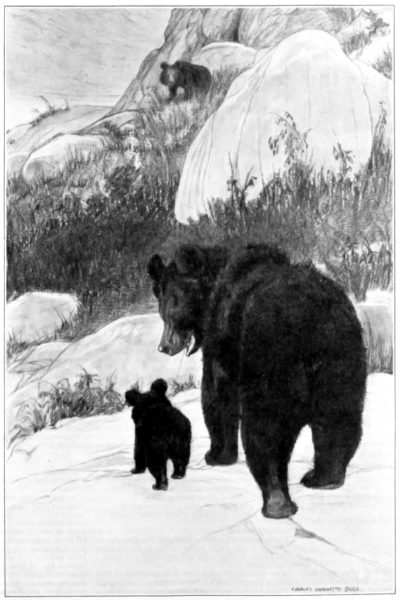

There was an interval in silence while the cub further tried himself out in front and his mother with folded hands surveyed the remains of the day. Then suddenly she was bowled over from behind — completely sprawled and walked on — and now standing in front of her and towering over her son was Himself. Life was very real and blithe to Skag, watching in the thicket not more than seventy yards away.

In the next two hours the two grown bears fed from the fringes of thicket on the knob. There were berries and bark and various podded seeds, which is garden truck for the big slow-feeding hibernators — hours of sniffing and threshing and pawing over to make a meal. Meanwhile the baby had no such trouble. He was warm fed before emerging from the den. This was still his mother’s affair anyway. All the shift he had to make for himself was in the spirit of exploration and discovery. He found the world enticing from all angles and hadn’t any particular use for alarm. That was left to the elders also.

He became infested with briers and squealed for his mother to come. She combed and carded him patiently enough until he did it again. Then she stood him on his head and thumped. Presently he sat down on his elbows and pawed into a decayed log. When he was tired with one little padded mit he tried the other. It was some distance from Skag’s screen, but the man now sensed what the end would be.

Red ants! They were doubtless swarming over the little chap before his absorption was broken. It would take some time for them to penetrate his inner coat, but penetrating is what red ants do best.

The little bear sat up and screwed his head round as if listening to himself. Then he stretched high on all claws looking back at different angles. The red ants had penetrated. They were connecting with pure tender cub meat at the roots of a thousand hairs. One small son became so intensely occupied with himself that for a moment he forgot to make sounds. Never before in all his interesting life had so many things been the matter with him at once. He got a sort of head spin working and out of the dusty shine of it. Skag presently heard his screams.

At this point, the mother bear crossed the knob.

Moreover, she came with purpose. She appeared to interpret the trouble from the nature of the screams. Past doubt she knew that log.

There are heroic treatments for Himalayan red ants. A gas tank is good, or a leap from a pier. Not having these at hand, the mother first of all broke the head spin and snatched the small one from the ant city and environs. Then she puddled and pestled him for many minutes in deep dust and took him to her heart.

“Carlin would appreciate that,” Skag muttered softly, letting out a long breath.

Now Himself was walking round his mate as she mended and mothered the grief of the cub. From a distance he appeared actually concerned and attentive, but Skag had seen him emerge from the den over her body — she taking the count after his wallop from behind. Also, he had not put out of mind the bad record concerning this parent which Carver had taken from the natives — the missing cubs and the gossip that involved extended estrangements between him and his mistress. Yet she seemed to hold no grudge against him now nor any alarm.

This mystery deepened. She plumped the infant down and went about her feeding. The little chap grieved a bit, finding himself alone, and scratched himself resentfully from various rests. But presently the broad sun-bright world took him again and he set out for a long walk — this time straight in Skag’s direction.

He couldn’t have been more than three months old. He was very black and round and perfect — still a soft one, in baby teeth and baby fuzz — so perfectly healthy that neither dirt nor grief could long adhere. He merely took the essence of his adventures, shedding the bumps and messes with a kind of winged ease — the plan of the universe being for joy, as he read it. Every passing wind fluffed and groomed him. Only occasionally, he stopped to scratch, trying a new method.

On he came in increasing delight in himself, alternating two and four feet, and very friendly with the ground. And now his figure was lost in the bushes not forty feet away from Skag’s screen. The man’s eyes were called presently across the knob to where one of the large bears was standing, head and shoulders above the small growth on that side. The great head moved slowly round, plainly searching the open for the little one. This was the old male evincing sudden concern for the cub.

Slowly and one-pointedly he crossed the area more or less in the small steps of the straying one. The point to Skag just now was how near the old one would come to him before finding the cub. Across the knob he saw the mother bear rise to her haunches. She could not have missed the purpose of her lord. Apparently she approved of it, for she dropped down and quietly resumed her feeding.

This to Skag was extraordinary, but he was by no means so occupied in the tension of the predicament as not to take a good look at the sire as he approached. Large, rotund, but with beaming countenance, as utterly far from anything malignant in appearance as a sun-bear toy. There was something of the aspect of an old doctor about him, one who had done so many good things for people for so many years as actually to have forgotten any other way to live.

The baby bear was very close, and his father might be expected to sense an intrusion before he reached the cub. Skag held himself quietly in hand, not moving a muscle, putting away the panic impulses of the mind one after another. The big bear halted at the edge of the thicket, sniffed, his manner changing to a sort of puzzled concern, but not in the least aggressive. There were low sounds in his throat, but far from growls. His son heard them, but this hedged-thicket life was quite as absorbing as outside. He was not in the least minded to go without force. The other sniffed querulously and plunged in. There was a squeal, but not from pain; rather the plaint of one dragged away from delightful activity. The two emerged together into the area side by side, crossing toward the mother, still quietly feeding across the knob.

Skag saw the gleam of firelight as he entered the darkness under the deodars. Carver had supper ready and the horses were feeding in grain bags.

“That’s a much-maligned old male,” Skag muttered a second time. “I’m not saying he’s above having wicked spells now and then, but he doesn’t look the part. Nothing meat-fed about his eyes.”

“He has a season’s work mapped out to undo his reputation with the natives,” Carver said.

“I’m far from sure he’s what they think,” Skag added quietly.

“But you say he knocked the madam down when he cared to come out.”

“Yes, and stepped on her. But I’ve been thinking that might be mere household usage in the High Hills. She didn’t hold it against him. I’m far from sure he’s a cub killer. He crossed the knob to collect the straying youngster and the mother went unconcernedly on with her feeding on the far side. Moreover, the cub himself isn’t afraid of his father.”

There was little sleep that night. There were sounds from the spring not to be interpreted. Skag had felt it necessary to tie the Arab short lest he burn himself on a long tether. He had been well grained since he could not pick any feed in the night, but he shivered as he stood, not with cold but with restlessness. Carver intimated that there were disadvantages about using a drawing-room mount for field work, but Skag surprised him by turning the Arab loose altogether.

Now the black one came even closer to their fire, instead of straying, and Skag felt the sweat of fear upon him. Carver was inclined to regard him as a bit oversensitive from prolonged and perfect stable care, but Skag knew something strange was in the air. He tried to listen with the same keen apprehension that the stallion did; tried to get the meaning from the winds that brought a troubling message to the keener nostrils of his mount.

The next morning, Skag minutely examined the spring. It was too leafy and tangled for him to discover any secrets, and where the water flowed under the vines all but the pebbles had been washed away. In the afternoon he went with Carver to the screen, but a second time the Englishman used up his inclination to wait before the bears appeared. Skag had had two hours of his sort of quiet sport and was more than ever convinced of the beneficence of the old male, when he thought he heard a shot and cry from someone far below. The bears were across the area and it was safe for him to leave.

Camp was strange even at a distance. The afternoon was still luminous, though the sun had gone down behind the big mountain. He missed the horses from under their tree. Carver did not answer his call. The Arab’s halter shank was broken at the knot and the long tether of Carver’s beast was gone, picket and all. Ashes and embers of the fire, now cold, had been threshed over the camp. There was blood upon the ground. All the play was gone from the still upper spaces; the clutch of grim finality was at Skag’s heart. Was it Carver? Was it the Arab?

Chilled and bewildered, Skag followed the spattered trail down the slopes, knowing he would not have far to go, because of the extent of the black-red waste upon the stones. And now queerly enough a certain pale hopeless look recurred to him from Carver’s face. It was a haunting sense of secret failure which Skag had never analyzed before, but it roved unmistakably now like a ghost before his eyes — the face of a man whose luck has been bad so long that he has come to expect no better. Skag wondered coldly why Carver’s hidden weakness came to him now. This wasn’t man blood. There was too much of it, if no other reason.

And now he saw the hump on the ground — a sudden revelation in the shadowed green. The strange laxity of a body in death always causes a start. It touched familiarly some inner sense quicker than the registration of the eye. The flanks were lying toward him. It was Carver’s pony — the head pulled forward to the knees. The throat was slashed open, the shoulders torn on each side, the spine laid open above the kidneys. The picture of what had occurred unfolded to Skag. The throat had been opened at the first stroke. That had happened above at the camp. The pony had broken loose and raced down slope until he fell.

The thing had come with him. The thing had not fed, unless a blood drinker. Perhaps it had been frightened away by Carver after the kill was made. And Carver had doubtless followed the Arab.

Now Skag’s eyes as he stood in intense silence caught a sudden speckled brightness above and to the right of the camp near the spring. It was a flash of mysterious gold light in the shadow — hardly like a body, but sinister in effect. Skag stood a moment longer, but saw nothing. Then with utmost stealth he made his way back along the ugly trail to the camp and above, circling round to a position above the spring, keeping covered in thicket but clear of the low-branched trees.

The bears had come down to the water. Skag was certainly puzzled at this moment. That gold flash in the shadow had nothing to do with bears. He saw the two broad black backs in the darkening green where the water washed the stones. He stared that way for several seconds trying to locate the cub. Then the old bears lifted their heads to peer over the thickets. They were looking for the cub too. The mother grunted impatiently. Skag could tell it was she by the waistline.

Now the two little curved front paws appeared, going somewhere, from the thick tangle round the spring to the open under the deodars toward camp. He had explored the thicket by the spring and found it tiresome. He approved of the broad dim aisles before him. Possibly there were enticing flavors in the air from the remains of the man camp. The mother grunted loudly again, but this only quickened the call abroad. Skag wasn’t in the mood for this sort of thing. The bears might go back to the knob as soon as they liked this once. The man wanted Carver — word from Carver and the Arab, and the meaning of the thin gold flash in the shadows.

Right then he got it — an apparition in gold and brown — a huge cat thing from the thicket below the spring, sleuthing the baby bear. This was Skag’s first look at the jaguar in India, as hard to find as the planet Mercury with the naked eye, the most secret and skulking of the great cats. Now the vile head moved roundly as he watched and stalked the cub — in a sort of half circle on a swivel that caught — all the bloodthirst and hate and secrecy of the jungle in the movement — lemon-green eyes of that cold which is on the other side of death, and writhing lips. The jaguar was mad and careless. He had failed to kill the night before. He had made a day kill just now and been driven away.

Skag suddenly loved that baby bear like the child of an old neighbor. The little chap was making straight for the man camp and one of its parents at least was still back at the spring. Skag had a pistol, but it is characteristic that his fingers reached first for a stone.

His movement to throw — and only the hand was visible — was caught by the cat before the stone left his fingers. The stone went wide. To the surprise of Skag, the beast crouched and held his place. Now the baby bear turned and there was a bleating cry from the red mouth — utterly startled and hopeless. The big cat was flattened to spring — the ears rubbed back, the whole figure seemingly fanned in a great wind.

Just at this instant Skag stood up. For a second time he broke the concentration of the killer that faced him fifty yards away.

And then the roar. That in itself was a revelation from the animal world. It was short. It was low as a grunt and yet held that impossible pitch, ripping forth as if bringing the heart of the mountain with it.

Skag’s standing up that instant had held the jaguar’s eyes long enough to give the great male bear advantage for his charge — a vast hurling forth from the thicket. The jaguar, caught too abruptly to run, turned, but did not rise — hugging the ground like a reptile, his body in a half curve like a scimitar. He reeled over on his back as the bear took and folded him in. And now the old sire screamed with pain. It was like taking to his chest two hundred pounds of molten metal — metal that must be crushed cold and very quickly before it burned too deep. To Skag from the distance it seemed that the bear was insanely threshing himself upon the ground. When he rose at last the gold-brown shadowy thing dropped from him and lay soft and stretched.

Skag’s eyes hurt from straining through the shadows. The mother went to her lord and helped to cleanse his wounds, taking his huge head in one paw and pressing it against her neck as she washed the hideous slash across his face. For many minutes she worked, the little chap coming close and watching with a dutiful attitude altogether strange. Night intervened before Skag heard the three pass the spring on their way up to the knob.

Skag meant only to pause at camp long enough to build a fire. It might possibly help Carver in, but the young Englishman’s hail was heard as the first smoke rose.

They looked at each other for a moment, silenced by so much to say.

“Your Arab is doubtless running yet,” Carver remarked. “No chance to come up with him, so I hurried in.”

He sank down, dropping his head on a saddle roll. His voice was very weary as he went on:

“It was strange — just staged to get a man’s nerve,” he muttered. “Why, Hantee, the thing couldn’t have looked dirtier. I was on the slope coming down to camp from your screen just as the jaguar dropped from a tree branch to my pony’s back. Both horses broke loose and the big cat rode my pony down the mountain. That’s the ghastly unforgettable part — to be ridden by that thing until he fell.”

“I saw that it must have been like that,” Skag answered, remembering the roweled shoulders and back. “And then you fired? “

“Just one shot, altogether out of range, as the beast stood over the fallen pony. He vanished. There was nothing to do after that but go after the Arab.”

“That’s a bad cat,” Skag muttered. “Possibly watched us all night from one of these trees. Yes, it was his taint in the air that disrupted the mount.”

Carter shivered, vetoing any idea of supper.

No, you wouldn’t be able to bring the Arab back here,” Skag added. “Not with blood on the ground and that thing lying below.”

“What thing — you mean the pony?” Carver asked wearily.

“No, the cub killer,” Skag said.

“Is — is the old father bear lying down there?”

“No, and the father bear is not the cub killer, but a most natural and estimable parent. I mean that bad cat you shot at. You spoiled his gorge from the pony and he went after the cub bear just a few minutes ago. Bear family was down to the spring, you see.”

“Carver,” Skag added, “there never was a straighter or quicker finish for a yellow cat, but I think I’ll feel better inside the head when that bear roar dies out — the roar when he charged — and the picture that followed.”

They had to wait for daylight to descend the mountain. The Arab had not gone back to Murree, but met them on open ground a half mile down the path — used up a bit, but not seriously harmed.

“I think he would have come in to camp,” Skag said, “except for the taint in the air.”

Carver did not answer, and Skag added with a smile: “I’m sorry about that brave little beast of yours, but for the rest — it’s been a rich two days.”

Illustrations by Charles Livingston Bull