How Nebraska Farmer Luna Kellie Was Radicalized Before the 1896 Election

In the late 1800s, one Nebraska farmer was beleaguered by an unruly farm, ten children, corrupt bankers, and indifferent politicians. She could have given up. But instead, Luna Kellie did something about it.

For most members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, a political advocacy group, the work of organizing occurred solely during the Alliances’ meetings and events. Yet for Luna Kellie, the Alliance’s secretary, the work often continued until the wee hours of the morning. As she later wrote in her memoirs, “if I had extra time when others were asleep, I would devote it to writings for the papers.” Kellie’s work for the Farmers’ Alliance eventually drove her to become a leader in the larger populist movement that swept through the U.S. during the 1890s. Yet even as she took on more responsibility, her political life and home life continued to intersect in the same way they had during those late night writing sessions. While Luna Kellie is far from being the most famous of the populist leaders, hers is the story of a woman driven to political action by personal hardship, making it particularly emblematic of the American political climate in the lead up to the pivotal 1896 presidential election.

St. Louis was a crowded town in 1876, and both Kellie and her husband J.T. felt that their dream for a safe and prosperous life was becoming more and more improbable in the industrializing city. So when the couple read a railroad advertisement for cheap homestead mortgages in Nebraska, they jumped at the opportunity. As Kellie wrote, “It seemed to me a great chance to see a beautiful country like the pictures showed and have lots of thrilling adventures.” A new life on the prairie also carried with it the promise of financial stability, a safe home, and a happy family. But in reality, Kellie’s new life was anything but the Little House on the Prairie. Instead, the newly Nebraskan farmer found that her farm’s success and her family’s well-being were at the whims of railroad magnates, cutthroat capitalists, and financiers in faraway states.

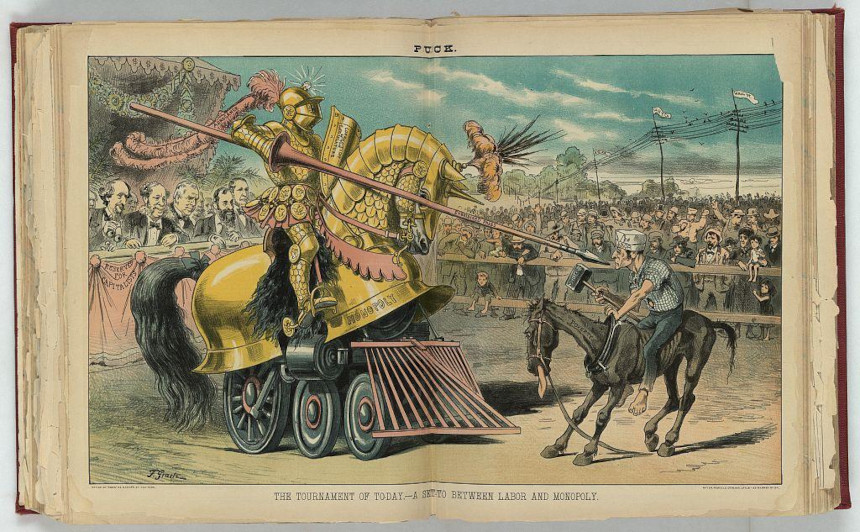

The decades after the Civil War promised a better life. Yet while the end of the 19th century was a time of widespread expansion, it was a time of even more widespread corruption. For freed African Americans, this corruption came in the form of Jim Crow regimes and new systems of oppression. For immigrants, it was political machines and decaying slums. For farmers — such as Kellie — corruption was apparent in the practices of railroads and banks that jockeyed for economic dominance over the vast expanses of the America west.

The end of the 19th century is called the Gilded Age on account of the decadence exhibited by urban capitalists such as Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, yet this same monopolistic impulse extended across the country. Kellie was quick to point out how such corruption was at play in Nebraska, writing that

even after they [the railroads] had made 4 times the necessary ‘expenses’ had they [only] been content with a profit of 1 million a month instead of 2. If they knowing the farmers were raising their stuff for them below cost of production had said we will divide the profit on each haul of wheat and corn each carload of stock with you we would not only [have] been enabled to keep our place and thousands more like us but would have been enabled to live in comfort and out of debt.

One bad harvest was all that stood between most farmers and financial ruin, a fact that hung like a shadow over Kellie and her family. Midwestern homesteads were plagued by environmental hazards, ranging from crop-eating grasshoppers to tornadoes and disease. Kellie experienced all of these trials, with the extra challenge of raising ten children at the same time. Additionally, the mortgage on Kellie’s homestead was handled by an apathetic bank in distant Boston. As the bank continued to raise interest rates, Kellie and her family faced the very real possibility of losing their land entirely. To combat this fear, she began selling vegetables in nearby towns as a source of supplementary income, yet she knew that quick cash was not enough to remedy the challenges her family faced. She had realized that her failure to find success and happiness in Nebraska was the result of an economic system that disempowered prairie farmers for the betterment of railroads, banks, and the bottom line. And so Kellie turned her energy towards organizing.

Farmers around the country were beginning to identify the systematic roots of their poverty (including Kansas farmers who eventually brought their issue to the House of Representatives). However, both major parties were controlled by northern industrialists who had no inclination to support homesteaders. As a result, the populist movement emerged in different pockets throughout the country, eventually coalescing as a third-party option to fight for the livelihood of farmers.

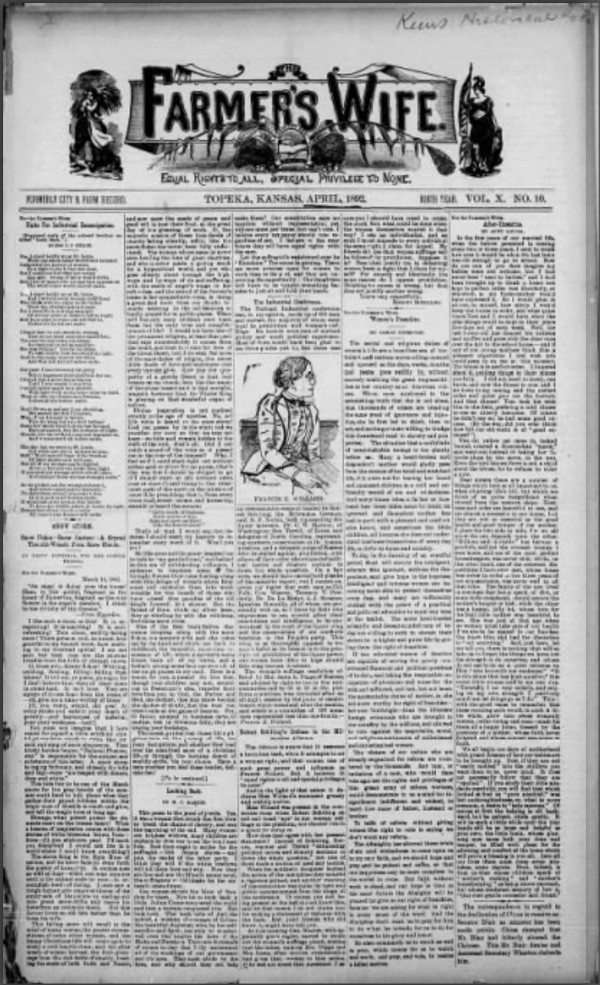

Though it may not have been clear at the time, Kellie was at the forefront of the populist movement in Nebraska. Both she and J.T. were members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, an organization that held town hall meetings and created literature that offered Nebraska homesteaders a voice in national politics. However, Kellie insisted that “the alliance at this time was not supposed to be political.” Instead, it was simply defending the work and lives of prairie farmers.

Still, Kellie continued to become more involved (much more than her husband) in the Farmers’ Alliance. She was elected as the organization’s secretary and took on the job of editing the Alliance’s newspaper, The Prairie Populist. In the paper, Kellie published biting condemnations of the railroads, bankers, and economic practices that had caused her family so much hardship. Her political awakening also extended beyond the needs of farmers. Kellie’s agency in the Farmers’ Alliance made her increasingly adamant about the need for women’s suffrage, and she soon took on the additional task of traveling to conventions around the country to fight for the vote. As The Scranton Tribune noted of one of her speeches, she “exerted her influence in favor of universal suffrage, undaunted by the fact that she was obliged to carry her baby with her during the long journey.” Kellie took on all of these new responsibilities while continuing to work on the homestead and raise her children, a feat that only strengthened the intensity of her political engagement.

As she traveled, Kellie earned a reputation for her fiery speeches. She was a songster, a type of public speaker who wrote political lyrics to well-known folksongs and would intersperse bits of verse throughout addresses. Luna traveled throughout Nebraska and its bordering states, engaging audiences of like-minded farmers with her urgent, song-infused speeches. The most notable of Kellie’s addresses was her “Stand Up for Nebraska” speech, which featured passionate lyrics about the deplorable practices of business monopolies and the financial security that Nebraska’s land should have provided:

Stand up for Nebraska! and shame upon those

Who fear the extent of their steals to disclose.

Who say that she cannot grow wealth or create;

But must coax foreign capital into the state.

Such insults each friend of the state deeply grieves:

Stand up for Nebraska and banish her thieves.

Through the Farmers’ Alliance, Kellie found her political voice to speak against the “foreign capital” of railroad companies and the larger wealth gap that was present throughout the United States. However, as the populist movement ballooned into a national third party, Kellie was quick to realize that the local roots and honest message of the Farmers’ Alliance was being corrupted. In the lead-up to the 1896 presidential election, the wildly successful populist candidate William Jennings Bryan agreed to combine forces with the Democratic Party and run as their candidate. So-called “fusionists” were in favor of this decision. People like Kellie, who believed that the populist movement’s central mission of helping farmers was being betrayed, did not.

Kellie continued organizing for the Farmers’ Alliance, but her premonitions were partly realized. Bryan lost the 1896 presidential election, and soon thereafter the Populist Party lost steam. It was perhaps the movement’s only chance at success on a national scale, and it was squandered. The community organizing that was the bread and butter of the populist movement faded into obscurity, and soon enough the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance also disbanded. Kellie continued speaking at conventions and fighting for women’s suffrage, but her political fervor waned.

Kellie continued working on her homestead, and many years later wrote a memoir for her family (which has since been published and serves as the principal source for this article). Quite poetically, she scribed the story of her life on the back of unused Farmers’ Alliance certificates. In its closing pages, Kellie offers a disillusioned soliloquy to the results of her political work. She writes, “And so I never vote [and] did not for years hardly look at a political paper. I feel that nothing is likely to be done to benefit the farming class in my lifetime. So I busy myself with my garden and chickens and have given up all hope of making the world any better.”

It is a heartbreaking sentiment coming from a woman who contributed so much to the populist movement, yet even Kellie’s own words might fail to capture the full scope of her impact. Luna Kellie’s goal was never to have a career in politics; still, she found widespread acclaim as a speaker, writer, and organizer. She was driven to politics by personal hardships, and even though the main cause she fought for may not have found success, she did succeed at giving a voice to the great number of people who faced problems similar to hers.

Featured image: Library of Congress