The Art of the Post: The Earliest Covers of the Post

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

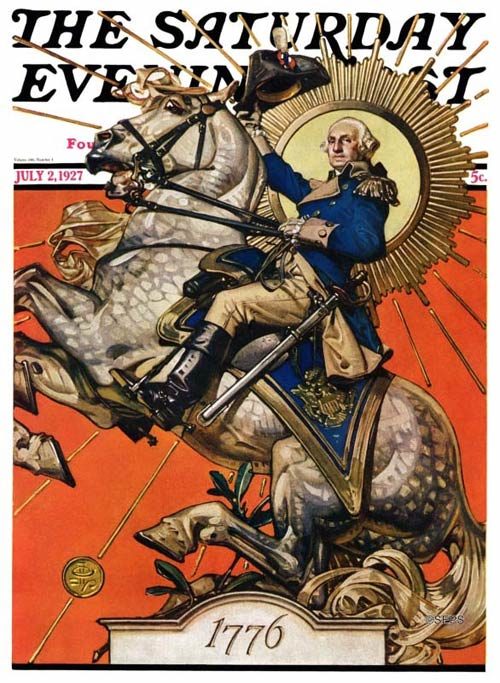

The Saturday Evening Post was famous for its colorful covers.

In his 1948 history of the Post, George Horace Lorimer and the Saturday Evening Post, John Tebbel wrote that the Post’s covers “were easily the Post’s most distinctive feature, its most popular single item and its greatest sales asset.” The Post’s editor-in-chief always chose the cover personally, applying very exacting standards. He would never trust such an important decision to a mere art director:

Lorimer picked the covers as a weekly routine, with the same unerring judgment he exercised on the editorial content. Fifteen or more cover candidates would be lined up on the floor, leaning against the wall, and the boss would walk past them like a general reviewing troops. As he made his rapid progress he would stab at them with a finger and keep up a running monologue: ‘Out, out, out, maybe this one, maybe, out, out, this one.’…. His genius for picking covers was affirmed time and time again by the evidences of their enormous popularity. In some Midwestern communities there were groups of readers who maintained betting pools on the topic of the next week’s cover.

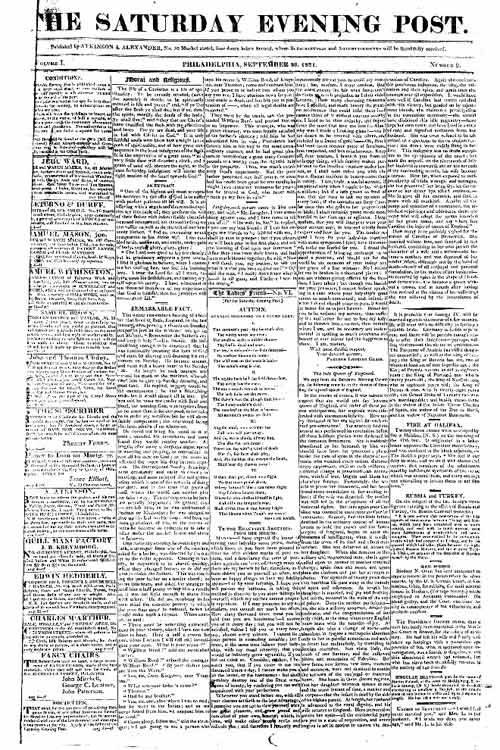

So it’s hard to imagine that, for much of its history, the Post had no cover picture at all.

The magazine began as text densely packed into tight columns on both sides of the page. It was up to the reader to visualize whatever was going on in the articles they read. The Post’s creative “look” was limited to a few different styles of typography. In fact, the Post might never have had its famous cover pictures if three crucial developments hadn’t come together simultaneously at the end of the 19th century. If any one of those developments had not taken place, the magazine revolution might not have conquered the world. As it was, the Post combined those developments to become the leading circulation magazine in the country.

Development No. 1: A New Kind of Paper Was Invented

In the beginning, paper was expensive, so magazines couldn’t afford the luxury of large pages and the empty white space necessary for illustrations and modern design. Through most of the 19th century, magazines were printed on paper made of “rag” content. Rag paper became even more expensive after the Civil War when supply could not keep up with increasing demand. After much experimentation, the paper industry finally produced new kinds of paper from wood pulp, paper that was strong enough to be used in the new high-speed rotary presses and durable enough so that it didn’t fall apart after multiple readings. It was clean and white, making a good platform for reproducing images. And perhaps best of all, the new paper was only 1/20th the cost of rag paper, so it gave magazines creative freedom to design larger and longer magazines with all kinds of eye-catching and imaginative formats. The cheaper paper reduced the price of magazines, making them accessible to masses of readers who previously couldn’t afford to subscribe. The price of the Post dropped to five cents, where it remained for decades.

The new paper was a great boon for magazines, but it wasn’t sufficient by itself.

Development No. 2: Better Ways of Reproducing Pictures Were Invented

When the Post began, it was difficult to print even the most basic black and white images, and they rarely turned out well. Crude images such as silhouettes of heads, pointing hands or simple graphic symbols were occasionally inserted into the text to sustain the interest of readers and give their eyes a little rest from long, monotonous columns of words.

These images were printed using woodcuts or wood engravings, carved by hand into actual blocks of wood, then inked and pressed against paper. This meant the images couldn’t be too complicated. They couldn’t be in color. They couldn’t be used for high circulation magazines because the wooden blocks would wear out after a limited number of printings. (Of course, high circulation was not a big problem. In the early days the Post had only a few hundred subscribers.)

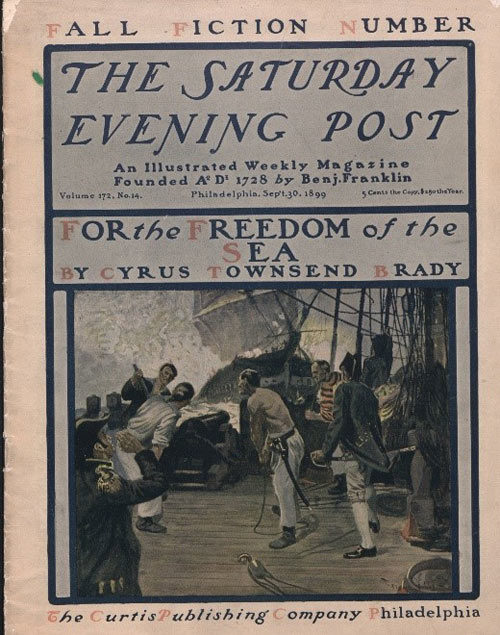

But by the end of the 19th century, innovations in printing technology enabled magazines to reproduce a wide variety of expressive, interesting illustrations. Photographic processes replaced the old-fashioned wood engravers. Quality artists were attracted to the field when they discovered their work could be reproduced accurately. Vivid color reproduction and halftone engraving served as a magnet for new readers. The first color cover of the Post appeared on September 30, 1899, at the beginning of a great surge in the Post’s circulation.

The new technique for printing pictures was a great boon for magazines, but even more changes were in store for the magazine business.

Development No. 3: A New Business Model Was Invented

Magazines were originally paid for solely by subscribers. As magazines learned to print more copies using new high-speed printers and deliver those copies to homes across a wider area using improved transportation, subscription lists grew. However, even with many new readers, magazines could never afford to hire the most talented artists in the land to paint large, full color oil paintings for illustrations. The crucial difference was a new business model: mass marketing.

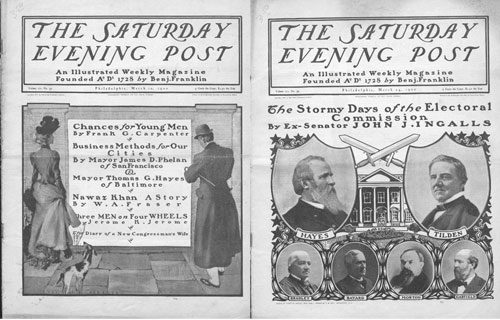

For most of its history, the Post rarely included advertising. In 1898 the Post was purchased by Cyrus Curtis (the Publisher of Ladies’ Home Journal) for a thousand dollars. At that time it had a total circulation of 10,473, and its advertising revenues for the July 1898 issue were a pitiful $290. Curtis hired a new editor, a visionary named George Lorimer, who saw the potential in the new developments described above — the better paper and the new printing techniques — and began transforming the Post with images. The first genuine full page cover illustration, proudly displaying what readers would find within, appeared in black and white on September 2, 1899.

But for Lorimer, advertising revenues were the engine that would power the growth of the new Post. The first full page illustration in the Post was not the cover but an advertisement for Quaker oats. Lorimer believed he could attract more readers with pictures, and that more readers would attract not only more subscription fees but also more advertisers. Lorimer increased the size of the page, making it more hospitable for big pictures. He expanded the length of the magazine to 24 pages (and suggested that it would soon grow to 32). He gambled much of the future of the magazine on pictures.

While this new content increased the cost of producing the Post, it also attracted millions of subscribers and made the Post the ideal forum for America’s new manufacturing industry looking for ways to market everything from soap to cars. The Post rapidly outdistanced all of its competitors as a way to reach homes across the country. Advertising revenues subsidized the 5 cent cover price and enabled the Post to commission brilliant illustrations for each issue.

Lorimer was said to have accomplished for the American magazine what Henry Ford did for the automobile. The new business model was a great boon for magazines, but it wasn’t sufficient by itself. If not for the new potential created by the development of new paper and the development of new printing capability, the new business model would not have become so successful.

A Magazine Renaissance

At the end of the 19th century the combination of these three developments led to the Post’s renaissance. The transformation didn’t take place instantaneously. During the transition the magazine sometimes offered hybrid covers that were half illustration, half table of contents.

But popular opinion became clear and there was no turning back. The cover pictures on the Post became an institution. New topics for covers were proposed not only by Post cover artists but also by readers and by the editorial staff of the Post who would come back from their vacations or business travel with lists of sights they’d seen that might make a good cover. Hollywood studios would contact the Post to get the name of a fetching model who had appeared in a Post cover. Everyone wanted to participate in the process, and that helped create the momentum that would serve the Post cover well for the next several decades.