Considering History: The New Deal, White Supremacy, and How the South Won the Civil War

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On April 9th, 1865, just under four years after the Civil War’s opening salvo at Fort Sumter, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Virginia’s Appomattox Court House, formally ending that divisive and destructive national conflict (although some Confederates refused to surrender for months thereafter). The attempt by 11 Southern states and a few Western territories to create a distinct nation organized around founding principles of slavery and white supremacy, the Confederate States of America (CSA), had failed, and the United States was reconstituted as a unified nation once more.

Yet over the next half-century, as I’ve written about for this column and elsewhere, a neo-Confederate perspective on American history and identity came to dominate the national landscape. A vital new book, historian Heather Cox Richardson’s How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America, links that trend to the development of and battles over the post-Civil War American West. But by the early 20th century a neo-Confederate, white supremacist narrative likewise dominated national politics and policy, as another of this week’s historical anniversaries can help us remember.

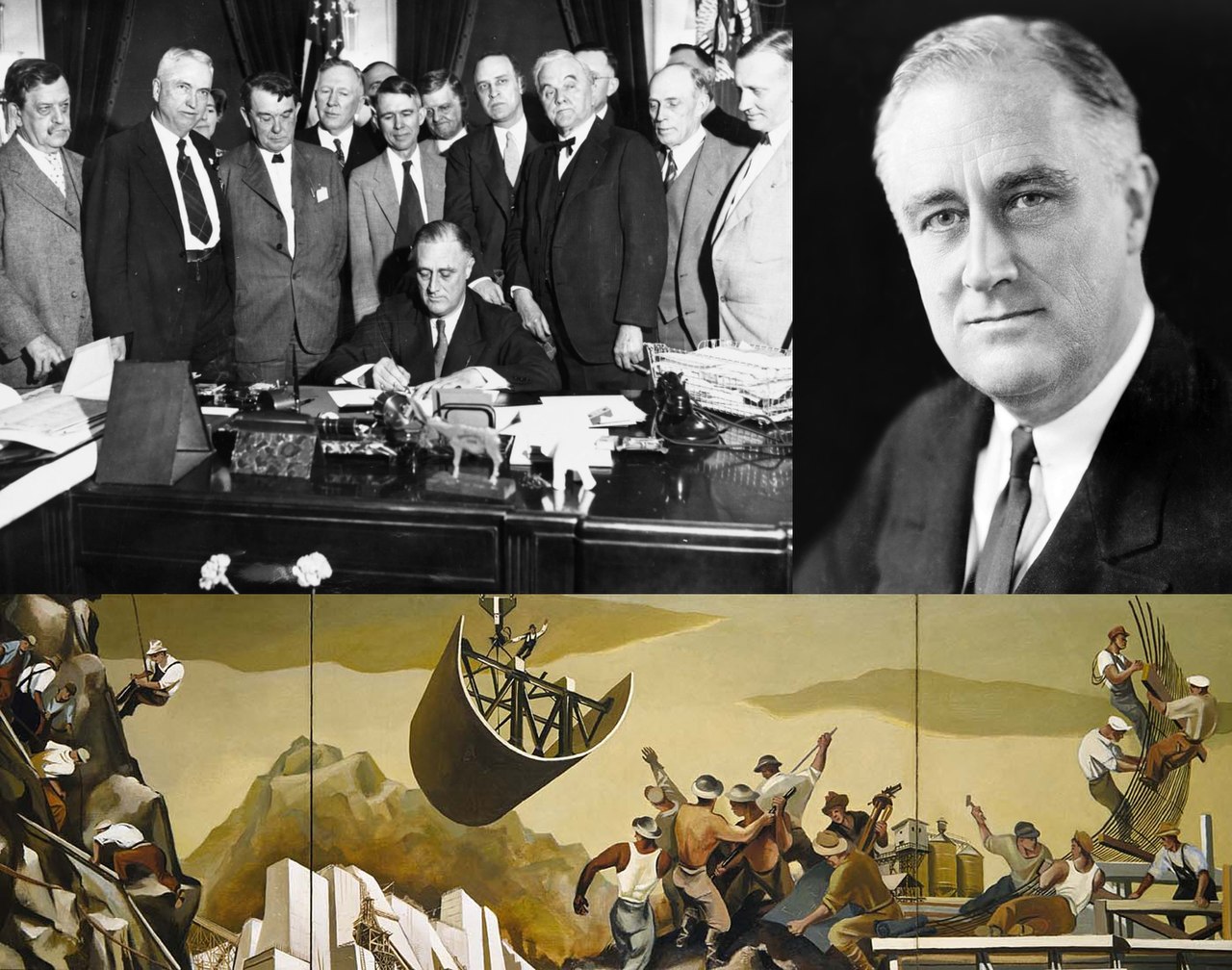

On April 8th, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, a request to Congress for $4.88 billion to create and support a number of public works programs within the overarching frame of the era’s evolving New Deal responses to the Great Depression. Although the Act’s targeted unemployment relief was controversial and much of it was eventually never allocated, the Act did lead directly to the creation of many of the New Deal’s most famous and successful public works programs, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and its subsidiaries such as the Federal Art Project and the Federal Theatre Project, the National Youth Administration, and the Rural Electrification Administration.

Yet the New Deal’s programs, like the Roosevelt Administration overall, consistently gave in to the demands of Southern white supremacists and discriminated against African Americans (and other Americans of color) in a number of distinct yet interconnected ways. Many of those Southern white supremacists were Democratic Congressmen whose votes Roosevelt was courting to secure passage of the New Deal, a political reality for the Democratic Party in this early 20th century period (before the party realignment of the 1950s and ’60s). Yet the very fact that Roosevelt needed those Southern Congressmen’s votes reflects the political and social power of this white supremacist community in 1930s America. And the various forms taken by these New Deal racial discriminations illustrate the destructive effects of white supremacy on millions of Americans.

The most overt such discriminations were the ways in which numerous New Deal programs were crafted to either exclude entirely or limit the opportunities of African Americans. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) excluded the African-American community overtly, refusing to guarantee mortgages for many African Americans seeking to buy homes; the Social Security Act (SSA) did so more indirectly but just as potently, excluding agricultural and domestic workers (two categories in which the majority of African Americans and many other Americans of color worked) from its protections. Other programs discriminated by creating segregated and unequal structures that mirrored Jim Crow systems: the National Recovery Administration (NRA) offered white Americans the first opportunity at its jobs, and paid African American workers substantially less; the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) maintained segregated and significantly less well-maintained camps for African Americans.

The exclusion of agricultural workers from the SSA was paralleled and extended by another, perhaps unintended but still hugely destructive form of discrimination, one exemplified by the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). As created by the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act, the AAA offered farmers subsidies in exchange for limiting their production, a policy intended to limit overproduction and help raise prices. But since many African-American farmers worked as sharecroppers, a system that developed alongside the re-emergence of Southern white supremacy in the late 19th century (part of what historian Douglas Blackmon has called “slavery by another name”), it was their white landlords who received the subsidies, and the farmers who were unable to produce and earn from their crops. The AAA thus pushed more than 100,000 African-American farmers off their land in 1933 and 1934 alone.

Beyond the New Deal’s programs and policies, the Roosevelt Administration likewise appeased white supremacists through its inaction on and even opposition to anti-discrimination laws in the period. The most prominent and ironic example was President Roosevelt’s opposition to an anti-lynching bill on which his wife Eleanor Roosevelt had collaborated with NAACP President Walter White and Congressional allies. Roosevelt told the pair in a private meeting that he could not publicly support the bill, arguing about the Southern white supremacists: “If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass the keep America from collapsing. I just can’t take the risk.” When the bill, known as the Costigan-Wagner Act, nonetheless came before Congress in February 1935, those Southern politicians threatened a lengthy filibuster, and the president remained silent; the bill died without a vote, and no federal anti-lynching legislation would ever be passed (until earlier this year, in a largely symbolic gesture).

The combined effect of all these discriminations and exclusions was that African Americans not only continued to occupy a significantly segregated and disadvantaged position in American society, but also did not receive the same benefits and opportunities from these vital programs as their peers — not during the depths of the Depression, and not over the decades since when many of those programs have continued to aid American communities. In his groundbreaking 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” journalist and public scholar Ta-Nehisi Coates argues that these discriminations (he particularly focuses on housing inequities such as those perpetrated by the Federal Housing Authority) have cost African-American individuals, families, and communities tens of millions of dollars across the 20th century and into the 21st, yet another profound and painful effect to the white supremacist perspective’s powerful hold on American politics and society.

Featured image: An artist’s rendering of the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. (Library of Congress)

On the Side of Social Security

Eighty-two years ago, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act, a part of the Second New Deal that provided the foundation of government assistance in the country.

Although the Post was often critical of federal and local relief programs following Roosevelt’s New Deal, Henry F. and Katharine Pringle’s “The Case for Federal Relief” in 1952 looked at the beneficiaries of welfare and argued the necessity of programs that give security to the unemployed, elderly, abandoned, and disabled. The authors asserted, “Public assistance does not make bums out of people, if it is accompanied by good social work. The right kind of aid, in money, for minimum security plus guidance to get the recipient back on his feet, if that is possible, is the answer.”

In 1952, the public wondered whether “hillbilly” children ought to receive funds for shoes — since they weren’t accustomed to wearing them — or whether releasing the names of people receiving public assistance might deter greedy deceivers out of embarrassment. Although most people tend to agree on a sort of social safety net, the implementation of such is rarely unanimous.